Wars are seldom won or lost due to a single event. Rather, the ultimate result is often preceded by a series of (sometimes) lesser connecting events. Pennsylvania loyalist Joseph Galloway criticized Sir William Howe and Lord Richard Howe for many of their military strategies in a blizzard of pamphlets written between 1780 and 1782. In all, he accounted for at least ten pamphlets, totaling over eight hundred pages. His writings were supported by extensive testimony, both by Galloway and the British military leaders, to the House of Commons in justifying their respective positions.

In Galloway’s judgment, probably the second most critical strategic military failure (after the failure to attack the Continental Army at Valley Forge) was General William Howe’s decision to strike a potentially demoralizing blow to the colonies by taking their capital, Philadelphia. Such a strategy was enshrined in European military doctrine, but this was a different type of war than one nation trying to subjugate another. In the context of British strategies, it exhibited in Howe a great misunderstanding of the enemy, the tactics and strategies necessary to defeat the rebel Americans, and probably cost the British their northern army under Gen. John Burgoyne in the battles at Saratoga. Because of his foray into Philadelphia, Howe was unable to create the planned cooperation of his army with Burgoyne’s, marching from the north, along the Hudson that would cut the colonies in two and fatally hamstring the American war effort.

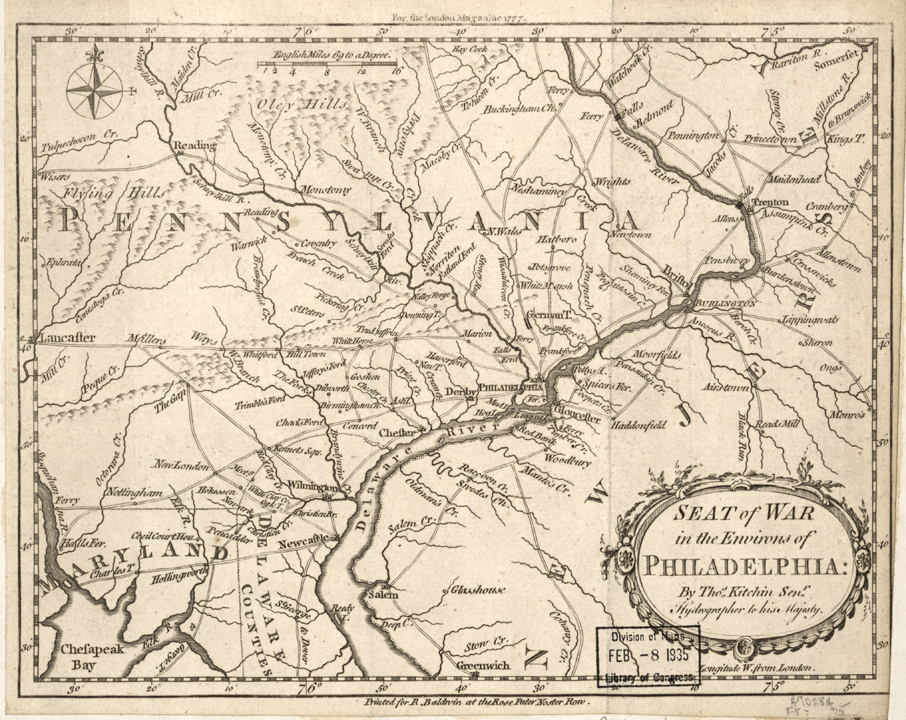

While Galloway, a Philadelphian, largely supported the decision to take Philadelphia, the way in which this was accomplished really raised his ire. The strategy that Howe employed effectively foreclosed any possibility of his helping the northern army. Philadelphia was taken not by a direct, overland march of some eighty miles, which probably would have taken several weeks, and could still have given Howe time to help Burgoyne. Howe chose instead to invade Philadelphia by sea with the support of his brother Admiral Lord Richard, and starting late in the campaigning season of 1777. Further compounding the failure was the decision to go by sea not on the most direct route from New York, which would be down the coast and up the Delaware River into Philadelphia. Rather Howe chose a circuitous route down to the Chesapeake before making the turn north, eventually coming through the Delaware, which cost two to three extra months. The former path, if things went as planned, may still have allowed Howe to extend some aid to Burgoyne. This would have been a big “if” given Howe’s reluctance to send off troops, but it was nonetheless a possibility. The final decision eliminated any chance of assistance getting to Burgoyne.

This decision by the Howes to go to Philadelphia by sea, much like General Howe’s decision not to attack Washington’s undermanned army throughout the winter of 1777-1778, on its surface seems somewhat inexplicable. There were several avenues of attack that Galloway used in criticizing the Howes. First, he criticized General Howe’s leisurely, late start in the campaign season. Galloway stated in his initial broadside on Howe, Letters to a Nobleman, that “the Commander in Chief never began his operations until the middle of June. A part of that month, and the whole of April and May, when the season is moderate, and most proper for action, and the roads are good, were wantonly wasted.”[1]

This late start was a huge factor in precluding any kind of mixed strategy where Howe could take Philadelphia and still have time to re-deploy a sufficient portion of his force to take pressure off Burgoyne—or, as Galloway suggested, sending a force of 2,000 to New England to cut off many of the forces that ended up strengthening General Horatio Gates’ forces against Burgoyne. “The necessity of this diversion on the coasts of New England with two thousand troops, was obvious to every man of sense,” Galloway wrote. “It would have prevented in a great measure the militia in that part of the country from joining Gates, and beyond all doubt it would have enabled General Burgoyne to have opposed with success the force with which he had to cope.”[2] Howe was aware of this as it was part of his original plan for the 1777 campaign, but apparently dismissed its significance.

Whether Howe would have helped Burgoyne directly or by reducing Gates’ potential force, or both, given his continual insecurity over the size of his force, is unknowable, but at least there may have been a chance for the planned severing of the colonies. As it went, it was Philadelphia and only Philadelphia, an outcome that would be further cemented by his decision to go to the capital via the Chesapeake.

One question worth asking is what instructions Howe was given by his leaders back home (mainly George Germain). How much did he know about the intended support of Burgoyne or even a planned action to New England? Did Howe communicate his intention to do something else, and was that approved? Howe attempted to reconstruct the narrative thread in his Response to Letters to a Nobleman.

Both Howe and Burgoyne had sent plans for the 1777 campaign to Germain in early 1777. Howe’s plan was three-pronged: An attack of an offensive force of a thousand men first on Rhode Island and then on to Boston, ten thousand troops to create a junction with Burgoyne along the Hudson, and lastly, eight thousand troops to menace Philadelphia from New Jersey, keeping Washington occupied and then taking the city (marching by land) in the fall. Burgoyne’s plan was pretty much the one he subsequently executed (absent the surrender part!).

Germain approved Howe and Burgoyne’s original plans in March, sending approvals which reached Burgoyne on May 6 and Howe on June 5. In between the submission of the original plans and his receipt of Germain’s approval of those plans, Howe squeezed in three changes via three different communications. The first was to his decision to take Philadelphia by sea instead of land, memorialized via an April 2, 1777, letter to Germain. The second was an April 5 letter to Germain stating that he could no longer support a meet-up with Burgoyne. Lastly, on June 3, only three days before he received Germain’s approval of his original plan, Howe sent another letter to Germain telling him the New England action was also out.

These letters, all sent before Howe started his 1777 campaign, illustrate the fraught nature of long-distance communications time lags, as on May 18, having not yet received any of Howe’s three changes, Germain sent Howe a letter again urging him to support Burgoyne. On June 5, the same day he received approval of his original plan from Germain, Howe wrote to Germain yet again. This time his request was for reinforcements, despite having abandoned two of the three prongs of his original plan.[3] Finally, Howe completed washing his hands of the Burgoyne support, asking Gen. Henry Clinton to cover the Burgoyne angle, advising him that “if you can make any diversion in favour of General Burgoyne’s approaching Albany, with security to King’s-Bridge, I need not point out the utility of such a measure.”[4]

The bottom line of all this correspondence is that Howe backed out of two of his three commitments before even making a move for Philadelphia and asked for more troops to boot! Additionally, he tried to push off the two abandoned prongs to Clinton, who eventually did provide some support for Burgoyne, though way too little and way too late. In Howe’s defense, he had not done anything in secret, having clearly advised Germain of his change in plans, though too late for Germain to do much of anything in the way of an alternate plan. To some extent Howe had to know that the turnaround of such communications would not allow Germain to respond to these changes, giving him what would be called in modern parlance “plausible deniability.” Essentially, he was working on his own. There was a lot of confusion in the communication between Howe and Germain, and much of this is due to long communication lead times. Howe had abandoned plans to support Burgoyne and Germain still appeared to believe that he would, due to one such crossing of communications. That Howe would no longer support Burgoyne supports Galloway’s accusation that the Philadelphia capture would result in just that, although Howe’s argument was that he had been quite clear about that in his communication.

Howe was not attempting to sabotage Burgoyne, but honestly pursuing a course that he felt would advance British war goals, though Galloway would come close to arguing that Philadelphia was a dalliance of little strategic value. It’s also not clear that, despite earlier plans to the contrary, Burgoyne really expected much in the way of support from Howe. Galloway’s reply to all this, in reaction to Howe’s explanation for his actions, was that “the plan of the Northern operations was the general’s own, not the plan of the administration: That he received written orders to ‘effect a speedy junction’ of the two armies and that junction was to be made at Albany” [italics in original].[5]

The voyage to Philadelphia did not leave until July 23, 1777, well into the campaign season by anyone’s measure. Galloway was also critical of this because it pushed the action into the hottest part of the year. “The troops were embarked in ships on the 5th of July, where both foot and cavalry remained pent up in the hottest season of the year, in the unhealthy holds of the vessels, until the 23d.”[6] Bypassing the more direct route up the Delaware, he arrived in the Chesapeake on August 5. In addition to the suffering of his army, his animals were decimated: “Many of the [horses], though in the highest health and vigor when embarked, were now dead and cast into the ocean, and the rest so emaciated as to be utterly unfit for service.”[7] Galloway also maintained that during this long period Washington had the opportunity to rebuild his army to a strength greater than he would have encountered had Howe either marched through New Jersey or even taken the sea route and turned up the Delaware. Washington also had a chance to solidify defenses on the Delaware (though he may not have known this was where Howe was ultimately headed). Galloway wrote that “he might blunder still more egregiously, that he might put his superior army to all the inconveniencies of a sea-voyage, that he might commit them to all the dangers of the ocean, and pass, perhaps, several thousand miles to meet that enemy, whom he had as much in his power as in his view, with double their force, and on stronger ground.”[8]

Ironically, Howe in response spun his use of the hottest part of the summer as an advantage, saying the time of the season was “in our favour . . . Our troops by being on board ship in the hot month of July and part of August, escaped an almost certain fatality by sickness, in which the enemy suffered much at that time,” exactly opposite of the conclusion Galloway reached. Howe feared the effect of the weather conditions had they taken a march, though Galloway ridiculed the calculus involved in this, stating that “the time which would have been lost in that march [through New Jersey in the heat] could not have been more than 10 hours. The time wasted in his Chesapeake circuit was three months.”[9]

Howe saw the invasion of Philadelphia as a way to draw Washington out of the cat-and-mouse he had been playing, believing that defending the capital would finally bring a direct confrontation between the forces. “It was incumbent upon him to risk a battle, to preserve that Capital. And as my opinion has always been, that the defeat of the rebel regular army is the surest road to peace,” wrote Howe.[10] It ultimately did do this at Brandywine and Germantown, though Galloway also expressed some issues about the way those battles were waged, particularly the latter where he ridiculed Howe for again failing to close the deal on Washington, as he pulled back his troops when a rainstorm set in. Lastly, Howe thought Burgoyne was more than capable of taking care of himself, especially “provided I had made a diversion in its favour, by drawing off to the southward the main army under General Washington.”[11] And Howe “concluded that the arrival of the northern army at Albany, would have given us the province of New-York and the Jerseys; all which events I was confident would lead to a prosperous conclusion of the war.”[12] As it turned out, that wasn’t enough.

Howe and Galloway also clashed on the diversionary impacts Howe’s execution of the Philadelphia campaign. Howe strongly argued that his foray to the south achieved a diversion of Washington’s forces from helping out Burgoyne’s opponent, Gen. Horatio Gates, averring that “A stronger diversion could not have been made, than that of drawing general Washington, and the whole continental army, near 300 miles off.”[13] Galloway’s response to this was that “the fact being, that Washington was only drawn, except for a few days . . . Fifty miles more distant.[14] He further disputed the diversionary value of Howe’s strategy, wondering whether Howe ““really imagine[d] that leading Washington, already two hundred miles from Saratoga, from Quibbletown [now New Market, New Jersey] to the neighborhood of Philadelphia, could possibly be a diversion of the least importance to the northern army? If Washington had intended to have cooperated with Gates against the northern army, could Sir William Howe think that he could prevent it by hiding his army in the ocean, and by his circuitous route to the Chesapeake, going 600 miles from Saratoga, and leaving Washington within 200 miles of it?”[15] “The general had really intended to prevent Washington from assisting Gates, why did he not take a post between them in New Jersey, on the only road and pass through which Washington could March?”[16]

Howe defended the Chesapeake versus Delaware decision by relying on the long and detailed testimony of Sir Andrew Snape Hammond, who oversaw the British command on the Delaware. After making many strategic points that went into this decision, Howe’s conclusion was that “There was besides no prospect of landing above the confluence of the Delaware and Christiana-Creek, at least the preparations the enemy had made for the defense of the river, by gallies, floating batteries, fire ships, and fire rafts, would have made such an attempt extremely hazardous.”[17] By the time the British arrived on the Delaware, the American defense consisted of, furthest south, one string of chevaux-de-fries (structures of heavy timbers with spears pointed downstream); Fort Billingsport, which was modified into a redoubt; a double chevaux at Billingsport; and furthest north, Fort Mercer on the Jersey shore and Mud Fort (also known as Fort Mifflin) on Mud Island across from Fort Mercer. Between these two fortifications was strung a triple chevaux.[18] A veritable obstacle course, but one through which the British managed to navigate to get to Philadelphia.

In Galloway’s view, the decision to go via the Chesapeake was ludicrous: “We next see him alter his resolution for one infinitely worse still, and to be equal by none, save that of going to Philadelphia by way of the West Indies, for he resolved to go to Philadelphia, by taking the course of the Chesapeake.”[19] Even Washington would find this so, claimed Galloway: “When it was suggested to him [Washington] that Sir William Howe was gone to the Chesapeake, he would not believe it, and contended that the measure was too absurd to be possible.”[20] But the Chesapeake it was, foreclosing any possibility of Howe coming to Burgoyne’s aid at Saratoga.

There are enough what-ifs in this scenario to keep armchair generals busy for a long time. What we do know is that Howe did eventually succeed in capturing Philadelphia in late September 1777. Despite getting the desired confrontations with Washington’s army along the way, he could not deliver the desired knockout blow. Burgoyne knew he wouldn’t be getting help from Howe and he wasn’t sure he needed it. He certainly did need it! He surrendered on October 17, 1777. Clinton made a late foray into the Hudson Highlands, including a capture of Fort Montgomery, but was not able to help Burgoyne other than to present a threat that probably panicked Gates into giving more generous terms of surrender than he should have.[21] Howe abandoned Philadelphia in June 1778, having held it for the winter and spring but having in the end gained very little by the occupation.

[1] Joseph Galloway, Letters to a Nobleman on the Conduct of the War in the Middle Colonies (London: J. Wilkie, 1780), 36-37.

[2] Ibid., 45.

[3] Kevin Weddle, The Compleat Victory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. The correspondence between Germain and the Generals is detailed in Appendix C, 402-405.

[4] William Howe, The Narrative of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe in a Committee of the House of Commons … To Which Are Added Some Observations Upon a Pamphlet Entitled Letters to a Nobleman (London: H. Baldwin, 1780), 23.

[5] Joseph Galloway, A Reply to the Observations of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe, on a pamphlet, entitled Letters to a Nobleman (London: G. Wilkie, 1780), 43.

[6] Galloway, Letters to a Nobleman, 69.

[7] Ibid., 71.

[8] Ibid., 66.

[9] Galloway, A Reply to the Observations, 82

[10] Howe, The Narrative of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe, 19.

[11] Ibid., 20.

[12] Ibid., 21.

[13] Galloway, A Reply to the Observations, 73.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., 76.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Howe, The Narrative of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe, 23-24.

[18] Harry Schenawolf, “Battle For the Delaware River in the American Revolution,” revolutionarywarjournal.com/battle-for-the-delaware-river-in-the-american-revolution-courageous-determination/.

[19] Galloway, A Reply to the Observations, 49.

[20] Ibid., 80.

[21] Weddle, The Compleat Victory, 337.

One thought on “William Howe: Taking the Slow Boat to Philadelphia”

Wading through over 800 pages of after-action reports and recriminations is a prodigious effort!

Howe was not as incompetent as Galloway indicated for a leisurely start to the 1777 campaign season.

Before the campaign to capture Philadelphia, Howe attempted to lure Washington from his fortified camp in the New Jersey hills into a general action by invading the former colony’s Raritan Valley and threatening Philadelphia. Washington failed to take the bait but sent a division to harass the British retreat to New York. On June 26, Howe ordered two columns to attack the probing Rebels. During their time in New Jersey, the British reportedly captured three brass cannons, killed sixty-three officers and soldiers, and wounded or captured two hundred more. Failing the safer strategy in New Jersey to destroy Washington’s army, Howe embarked on the Philadelphia campaign by sea. Apparently, Galloway omitted the New Jersey effort in his criticism of starting the campaign late in the fighting season.