Governance under the federal Constitution transformed the nature and style of American politics. The spirit of this transformation revolved broadly around fear of political corruption and the vaguely defined yet delicate balance between national authority and state and local power.[1] And while the new republic’s first elected officials deliberated the nation’s most pressing issues in New York and later at Philadelphia, it was print media that brought these spirited debates into the homes of ordinary Americans.[2] Once divergent republican worldviews found representation in competing gazettes, partisan loyalties quickened the formation of national proto-parties, an alarming development neither foreseen nor desired by the political community.[3] Partisan printers informed readers of the principles behind party positions, joined individuals from disparate geographies in political union, and, ominously, identified domestic opponents as enemies who threatened the liberal bounty of the American Revolution. Yet before the political environment descended into crisis, one inspired editor relocated to the national capitol hoping to serve as a medium between the new government and the reading republic. John Fenno calculated that his support for the new Constitution would help foster a single, national people firmly committed to the federal government and its administrations. His gazette, he expected, would at once speak for the government and to the people, extolling federal virtues while instructing popular deference to national initiatives and statesmen. For John Fenno, nationalizing the public character became his private passionem, his secular crusade.

Boston’s John Fenno was born in 1751, the son of struggling leather dresser Ephraim and dutiful homemaker Mary Chapman. Fenno benefited from a public-supported education at Albiah Holbrook’s Old South Writing School where he, some years later, became a teacher alongside his close friend Joseph Ward.[4] Fenno, like his father, found himself chasing an elusive upward social mobility just as the American resistance effort became militarized.[5] Possibly through his friendship with Ward, Fenno joined Gen. Artemas Ward’s staff, serving until the latter’s resignation in 1777.[6] Fenno next married Mary Curtis, a daughter of local loyalists, and simultaneously started a family and trade business. Sadly, the Fennos struggled financially during much of the 1770s and into the 1780s.[7] Fortune finally smiled upon John Fenno when he made the acquaintance of editor Benjamin Russell. Russell, a committed nationalist, owned and operated the Massachusetts Centinel (later Columbian Centinel), which unabashedly espoused nationalist (and later Federalist) positions.[8] Sharing the same political persuasion, John Fenno became a natural fit to contribute to Russell’s gazette. While producing for that paper, Fenno’s obvious intelligence and literary talents caught the attention of a wider audience. Critically, he also learned the artisanal end of the printing trade.

John Fenno’s polished prose and deep commitment to the new federal Constitution brought him into the orbit of some of the most influential nationalist thinkers in Massachusetts.[9] And when New York ratified the Constitution on July 26, 1788, Fenno devised a plan that harmonized perfectly his printing and writing prowess with his sincere devotion to the proposed new federal order.[10] As Massachusetts Federalist Christopher Gore explained to New York’s Rufus King, “my friend Mr. Fenno . . . has conceived a plan, of publishing a newspaper . . . for the purpose of disseminating favorable sentiments of the federal constitution, and its administrations.” Gore proceeded to laud Fenno’s character and editorial skill before declaring him “capable of performing essential service in the cause of federalism and good government.”[11] Fenno’s own thoughts on the importance of print culture were exceptionally perceptive. “The general diffusion of knowledge which has arisen from the production of the press,” he recognized, “may be ascribed the rise, progress, and honourable termination of the American Revolution.” The press, he continued, also played no small role in getting the Constitution ratified and, for Fenno, the adoption of the new government represented a “complete triumph of reason.” Yet the political storm was not over, Fenno warned. The American public needed the press more than ever, he reasoned, to help familiarize citizens with the perceived wisdom of the Constitution, that “palladium of their Rights and Liberties.”[12]

Modern scholars have just recently begun to uncover the critical role print media played in forming a recognizable and viable public, attributing the creation of the modern world to the diffuse and dynamic world of letters.[13] So when Fenno credited print culture with creating and curating a political nation, he revealed a sophisticated analysis of how news, thought and participatory literacy fosters community despite the challenges of geography. His sensitivity to this intellectual connectivity divulged his nuanced understanding of how a body politic is formed; it also showcased his critical recognition of news media’s political utility.

John Fenno drafted a mission statement to help secure patronage and financial assistance for his national project and called upon all individuals supportive of the Constitution and good government to subscribe to his paper. His publication, he proclaimed, was “to be entirely devoted to the Constitution, and the Administration formed upon its national principles.”[14] Fenno received a $235 loan from several of Massachusetts’s staunchest defenders of the new Constitution in January 1789. The loan’s terms allocated this advance to the establishment of a gazette printed at the seat of government “calculated to promote the public good.” Some elite members of the merchant class signed on, as did two elected members of the Federal Congress—even Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin helped subsidize this effort.[15] Clearly these men held Fenno’s intelligence, work ethic and political persuasion in high regard. What is equally worth digesting, however, is just what this endeavor demanded of Fenno. He believed so deeply in the potential value his paper held for the national future that he relocated, indefinitely, from Boston to New York and then, following the seat of government, to Philadelphia. The people, places and institutions that shaped Fenno into the man he became faded into but memories once he packed up to nationalize the literary citizenry. He did not know it at the time, but he would never make it back to Boston.

Fenno estimated startup costs for a press and types at $200 and figured he would require an additional $200 to hire assistants, temporarily support his family and cover any unforeseen expenses. He held out hope that successful execution in service of the government would earn him the printing patronage of Congress and/or the executive departments.[16] By the end of January, Fenno had made his way to New York and immediately set about ingratiating himself with elite nationalists. He remained busy nearly every waking hour and agonized over the prospect of supporting his wife and children once they made their move from the familiarity of Boston to the capital’s bustling streets. Fenno explained to Joseph Ward that many of the influential men he sought were engaged in the public’s business. “Col. [Alexander] Hamilton I saw for the first time to day,” he reported to Ward, and Hamilton expressed optimism that “success would attend the undertaking [Fenno’s gazette] if judiciously managed.” In fact, “the project,” Fenno enthused, “has met with universal approbation.” The intrepid printer prepared himself for the ridicule and political venom of his anti-federalist enemies, thundering “If they should belch out lies, let them know it.” Fenno expected his gazette to “confound the Anti-Federalist Junto.”[17] He had arrived at his Jericho.

By early February, Fenno had still not secured an office or printing press. He kept his ear to the ground politically and shared with Ward that there was a movement afoot to remove New York’s Gov. George Clinton.[18] He predicted that if this came to pass, New Yorkers would embrace the federal government and despise anti-federalists for their “deficiency of Wisdom, honour, and patriotism.” All the while, he remained obsessed with obtaining “a slice of the Printing Loaf” and if that Holy Grail of letters did not materialize, he planned to work as a residuary agent for the new government.[19]

Finally by April, Fenno’s printing office was up and running and he published the first edition of his Gazette of the United States on April 15, 1789.[20] Yet Fenno still had logistical challenges to surmount, writing that it was “mortifying” to learn he had worked all through the night each Tuesday only to discover his paper did not reach New England in a timely fashion.[21] He feared precious patrons would cancel their subscriptions should his paper continue its tardy arrival. And he desperately needed every customer.

What Fenno’s letters make clear is that his devotion to the national cause and the long hours he dedicated to it took a profound physical and emotional toll on him. “I wish to be an auxiliary to good government,” he expressed, asserting “the Constitution is the only ark of safety to the liberties of America . . . it will be a pleasing task to me, to enter into a hearty and spirited support for the administration so far as they appear to be influenced by its genuine Principles.” He closed these remarks with a near-secular prayer, hoping that “conscience, duty, and patriotism would unite in promoting my exertions.”[22] And his exertions were tremendous.

In July, Fenno recorded that he had about 600 total subscribers and added between six and twelve additional patrons each week. As encouraging as these figures appear at first glance, however, he followed this news by estimating he would need about 1,500 subscriptions to “at least afford a subsistence.” Until then, “my time and labour . . . have hitherto gone for nothing.” He next revealed the lonely routine he adhered to each day: “I go into no Company—my only rout is from home to Congress, and from Congress to home, week in, and week out.”[23] In another letter, he sadly disclosed that he lived “so recluse a life that I know little of what is going forward in the world.”[24] His business required that he attend every congressional session to absorb and produce the political content contained within the pages of his paper. Conveniently in 1790, the House of Representatives had designated four seats in its chambers to reporters attending its sessions. By 1795, the more secretive Senate had followed suit.[25] Freneau further commented that his work rhythm was so arduous that he had lost noticeable weight, sighing, “Some say I am thin.”[26] Fenno’s rigid routine was not limited to simply supplying the intellectual content of his gazette; he also physically labored behind the press to produce his paper. He faithfully haunted both chambers of Congress and spent hours in his print office, part of the burden he undertook during his political crusade to elucidate the public mind.

Another lamentable element of Fenno’s private crusade involved the personal grief he dealt with during its pursuit. While his head necessarily focused on business and politics in New York and later Philadelphia, his emotional self hovered over Boston. In 1789, Fenno’s sister lay dying and he became overcome with guilt since he could not be with her, given the vast geography that separated the siblings. Yet he also remained in New York due to professional and financial demands.[27] In addition, his ailing father ended up in an almshouse in Boston and Fenno learned his close friend, Joseph Ward, had lost his brother. Indeed, in several years’ time, Fenno, plagued with debt, paralyzed with unprofitable work and sickly, had lost two young daughters, a sister, and his father.[28] Ward lost a sibling and, devastatingly, his five-year-old son.[29] Yet even with debt and death interwoven into this narrative, Fenno remained deeply involved with public affairs. He convinced himself that his paper could provide a civic education to the political nation and persuade a majority of Americans to support the federal government and Constitution. His tireless work ethic and principled commitment to his cause may also reflect a much needed distraction (albeit a costly one) from the constant human suffering he endured.

In October 1789, Fenno learned that both President Washington and second magistrate John Adams, “expressed themselves pleased” with his literary politics. Washington, Fenno gushed to a friend, even “mentioned it [the Gazette of the United States] in terms of warm approbation in some of his private letters to Virginia.” As a result, Fenno benefited from some modest patronage from the president’s office as well as the war and state departments.[30] Before the end of his first year of publication, however, Fenno, “with great regret,” opened his paper for advertising to generate some reliable income.[31] And despite the patronage and adverts, he remained in chronic debt and utterly dependent on loans.[32] By April 1790 Fenno had over 1,000 subscribers and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson had granted him “the publication of the laws.” He likewise gained “all the Senate business,” but sadly these printing contracts brought him little relief.[33] Hamilton provided Fenno with two generous financial gifts, a clear recognition on the secretary’s part of the political value and future potency he envisioned from Fenno’s efforts.[34]

Just as John Fenno had begun to settle into his new home, profession and grueling work routine, he learned Congress had engaged in discussions to relocate the national capital. Fenno, not unreasonably, feared Congress’s next session would be held at Philadelphia. This move, an exasperated Fenno gasped, “would be an almost ruinous derangement for me.”[35] By early July, Congress had passed the Residence Act; Washington signed it into law on July 16. Fenno opened a new office on Market Street by early November and in December, Philadelphia became home to the national government.[36] This naturally shifted the republic’s political gravity south, much to Fenno’s emotional, geographic and financial distress. In fact, Fenno’s wife had to resort to renting rooms in their home to several Federalist congressmen to make ends meet. Indeed, representatives Peleg Wadsworth and Peleg Coffin of Massachusetts and Uriah Tracy of Connecticut each became the Fennos’ boarders for at least part of their tenure in Congress’s lower chamber.[37] Unfortunately, even this did not bring the indefatigable printer solvency. Plagued with misfortune, he balanced on the verge of financial ruin.

In the summer of 1793, Fenno’s plight worsened as Philadelphia became ground zero for a yellow fever outbreak. This caused him to suspend publishing his paper for roughly three months. All the while he kept Joseph Ward informed of the horrors unfolding around him. “I steal a moment to inform you of the dreadful Situation of this City,” he reported. According to Fenno, about fifty people a day succumbed to the infection and, he grimly noted, seventy “Children . . . have been made orphans by this Epidemic.” Fenno found some optimism in President Washington’s impending return to Philadelphia. “The president,” he enthused, “intends to set off for this City in a few days. His presence, will greatly conduce to restoring general Confidence.”[38] Fenno, already dancing on precarious financial footing, only saw his situation worsen due to the pandemic.

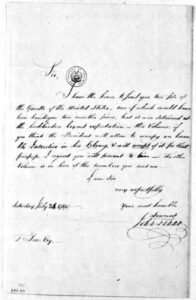

By the end of 1793, Fenno found himself in such dire straits that he had to approach Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton for emergency financial assistance. “I am reduced to a situation so embarrassed, as incapacitates me from printing another paper, without the aid of a considerable Loan,” he desperately informed Hamilton. Fenno’s debts were piling up; he could not afford paper, ink or postage for correspondence and many of his patrons had simply failed to pay for their subscriptions. “Four Years and an half of my Life is gone for nothing; and worse,” he lamented, “if at this crisis, the hand of benevolence & patriotism is not extended.”[39] Hamilton, recognizing both the political value of Fenno’s continued effort and the humanity in the printer’s plea, fired off a missive to Rufus King. “Inclosed [is] a letter which I have just received from poor Fenno. It speaks for itself. If you can without delay raise 1000 Dollars in New York, I will endeavor to raise another Thousand at Philadelphia. If this cannot be done,” the New Yorker rationalized, “we must lose his services and he will be the victim of his honest public spirit.”[40]

John Fenno, for his part, occupied a strange space in the early republic. He was a man of clear intellectual distinction who engaged in a labor-intensive craft. Sadly (and unlike idiosyncratic printer-philosopher Benjamin Franklin), he remained in a chronic state of financial insecurity despite his best efforts.[41] Fenno found himself a philosopher toiling behind a press, oddly combining, in his own way, letters and labor. “The Printing business is very peculiar,” he noted. Though “artists in that line deal wholly in Letters, yet [it] is notoriously the Case that there are as few Men of ideas in that profession as any other whatever.”[42] In other words, Fenno observed that while printers traded in literacy, few possessed learning enough to offer their own thoughts. In contrast, Fenno saw his gazette, a paper fueled by his ideas, as a vehicle with which to proselytize the masses into supporting the Constitution. And unlike the typical printer, he supplied both intellect and industry. In modern parlance, he simultaneously fulfilled the roles of editor, reporter and printer. Fenno expected to eventually lift himself out of printing’s drudgeries and focus on contributing his ideas and political connections to his paper. He never realized this “genteelification,” so alluring yet so evasive in eighteenth-century America.

In 1798, yellow fever again swept through Philadelphia. Fenno’s final known letter to Joseph Ward, written on August 30, captures the terror that once again gripped that city’s streets while that mosquito-borne infection decimated the local population.[43] “The City is now deserted and desolate,” Fenno reported, and the “disorder we have is a most terrible one, and makes tremendous ravages—few lay longer than four or five days—many die sooner and you will see by the papers that the proportion of the Dead to the sick is very great.” The editor also estimated the viral illness carried away about forty people each day. Yet even in the face of indescribable suffering and death, Fenno, cramped together with his sickly wife and their five youngest children, continued his crusade.[44]

Since rival editor and (generally) Democratic-Republican Benjamin Franklin Bache planned to continue printing in the city, Fenno also determined to stay his course.[45] “As it is my duty to continue here so long as other printers remain at their Posts,” he martyrized, “I shall remain also, trusting in that almighty power which has so graciously protected me and mine heretofore.” Fenno’s level of commitment, aided by his belief that the creator of the universe favored his mission, suggests he was a fanatically-obsessed or theologically-driven partisan. It could also be, however, that Fenno rooted his political faith in the universality of justice. He routinely described his opponents as dishonest enemies of the republic. So when facing down death, his pursuit of justice and pugna against injustice became even more critical. He closed his final letter to Ward: “Wishing that we may see universal peace, righteousness justice and truth prevail thro’ the Earth.”[46] Opponent Bache fell ill with yellow fever on Friday, September 7. He was dead by Monday. Four days later, Fenno also succumbed to that dreaded malady.[47]

The following Monday, September 17, 1798, the latest edition of the Gazette of the United States made its way to publication. Within its pages appeared the following announcement. “Died, on Friday evening last, Mr. John Fenno, late Editor and Proprietor of this Gazette. The Gazette of the United States will in future be published under the direction of John Ward Fenno, son of the deceased.”[48] A striking irony is to be found in the date of this grim advertisement. John Fenno dedicated his adult life to supporting the federal Constitution. Ten years earlier (to the day), delegates had signed the engrossed Constitution at Philadelphia.[49] Ten years later, a divided American public learned that that document’s greatest street brawler had died defending it during a horrifying pandemic. Fenno remained committed to the end.[50]

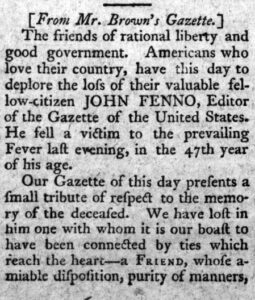

A more detailed obituary also alerted the political world of Fenno’s departure. As reported in the September 25, 1798 edition of the New Hampshire Gazette:

The friends of rational liberty and good government, Americans who love their country, have this day to deplore the loss of their valuable fellow citizen, John Fenno, Editor of the Gazette of the United States.—He fell a victim to the prevailing fever last evening, in the 47th year of his age.

Our Gazette of this day presents a small tribute of the respect and memory of the deceased. We have lost in him one with whom it is our boast to have been connected by ties which reach the heart—a Friend, whose amiable disposition, purity of manners, and integrity of soul, rendered him the delight of all who knew him. The Gazette of the United States will in future be conducted by Mr. John Ward Fenno, son of the deceased.[51]

John Fenno’s private crusade to create an American character is an often overlooked part of the national narrative. For all the ink scholars spill on the founding statesmen, they less commonly dignify workhorses like Fenno (and other street-level partisans) with agency or gravity of consequence. And while the glory and secular immortality will likely remain the fruit of the framers and their inner circle, without the herculean efforts of men like Fenno, the political nation would have been less informed and more disjointed.[52] Few partisans of either political persuasion endured the suffering Fenno did for as little reward. Who among his ilk proved willing to fundamentally uproot themselves professionally and geographically in order to defend a private notion of the public good? And like his father, Fenno also never realized that elusive socio-economic ascent. John Fenno’s final stage of life brought him only debt, death, isolated working hours and the ire of his enemies. An image of the man, if one ever existed, does not survive or remains unidentified. And his name and industry on behalf of the new national order is almost never reflected within the pages of standard modern textbooks. But the full extent of his labor is memorialized in the public record. The man’s private thoughts meshed so perfectly with his public objectives that it is virtually impossible to extricate one from the other. Like the Roman poet Ovid, John Fenno’s public work subsumed his private identity.[53] Fenno is mainly to be found, like Ovid in his Metamorphoses, in the annals of his effort: the pages of the Gazette of the United States. Fenno, a skilled writer and deft thinker, once marveled, “What magic there is in some words!”[54] And millions of his words, the ultimate product of thousands of hours of intensive intellectual and physical engagement, remain silently entombed in the yellowed pages he left behind. This collection of public papers is John Fenno’s modest monument to the federal republic.

[1] For some valuable explorations into ideological conflict, republican virtue and political corruption in early American constitutional politics, see Colleen Sheehan, James Madison and the Spirit of Republican Self-Government (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Saul Cornell, The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788-1812 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999); James Roger Sharp, American Politics of the Early Republic: A New Nation in Crisis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993); Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1985); Herbert J. Storing, What the Anti-Federalists were For: The Political Thought of the Opponents of the Constitution (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981); Lance Banning, The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of an Ideology (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978).

[2] For two outstanding surveys of print media and its functions in the early republic, see Jeffrey Pasley, The Tyranny of Printers: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2001); Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility: Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy (Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[3] For the formation of political parties, see Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 296-300; Sharp, American Politics.; Banning, Jeffersonian Persuasion.

[4] This biographical survey is from John B. Hench, ed., “Letters of John Fenno and John Fenno Ward, 1779-1800, Part 1: 1779-1790,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 89, no. 2 (1979); See also Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 25-27;

[5] For John Fenno’s pursuit of upward social mobility, see Pasley, Tyranny of Printers, 51; Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 25-28.

[6] Rebecca Anne Goetz, “General Artemas Ward: A Forgotten Revolutionary Remembered and Reinvented, 1800-1938,” in Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 113, no. 1 (2003): 103-34.

[7] Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 25-27.

[8] Jerry W. Knudson, Jefferson and the Press: Crucible of Liberty (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2006), 27, 35.

[9] See Pasley, Tyranny of Printers; Daniels, Scandal and Civility.

[10] For New York’s ratification, see Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1776-1788 (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2010).

[11] Christopher Gore to Rufus King, January 18, 1789, in Charles R. King, ed., The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King: Comprising of His Letters, Private and Official, His Public Documents, and His Speeches, 6 vols. (New York, NY: G.P Putnam’s Sons: The Knickerbocker Press, 1894-1900), 1: 357-58.

[12] John Fenno, January 1, 1789, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 89, 1:312-14.

[13] Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (Cambridge, NY: MIT Press, 1991); Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983); Michael Warner, The Letters of the Republic: Publication and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century America (Cambridge, NY: Harvard University Press, 1990).

[14] John Fenno to Joseph Ward, January 1, 1789, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 89, 1:312-14.

[15] Fenno Loan Terms, January 1, 1789, in ibid, 1:311.

[16] Fenno to Joseph Ward, January 1, 1789, in ibid.

[17] Fenno to Ward, January 28, 1789, in ibid., 1:315.

[18] For more on the effort to defeat George Clinton in New York, see also Alfred F. Young, The Democratic Republicans of New York: The Origins, 1763-1797 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1967), 277-341.

[19] Fenno to Ward, April 5, 1789, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1:324.

[20] Gazette of the United States, April 15, 1789; Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 37-39.

[21] Fenno to Ward, June 6, 1789, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1:325.

[22] Fenno to Ward, August 5, 1789, in ibid., 1:334.

[23] Fenno to JosephWard, July 26, 1789, in ibid., 1:331-32.

[24] Fenno to Ward, March 7, 1790, in ibid., 1:358.

[25] Knudson, Jefferson and the Press, 9.

[26] Fenno to Ward, January 31, 1790, in ibid., 1:357.

[27] Fenno to Ward, April 5 and June 6, 1789, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1:324-27.

[28] Fenno to Ward, December 5, 1789, May 16, 1790, November 14, 1789, and April 6, 1793 in ibid., 1: 350, 344, and 2: 167.

[29] Fenno to Ward, November 14, 1789 and April 6, 1793 in ibid., 1: 344, 2:167;

[30] Fenno to Ward, October 8, 1789, in ibid., 1: 339-40.

[31] Fenno to Ward, November 28, 1789, in ibid., 1: 348.

[32] Fenno to Ward, November 28, 1789, in ibid., 1: 348.

[33] Fenno to Ward, January 31, 1789 and April 11, 1790, in ibid., 1: 357, 359.

[34] Pasley, Tyranny of Printers, 200.

[35] Fenno to Ward, May 23, 1789 in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1:364.

[36] For more on the Residence Act of 1790, see Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009), 79-80 142-43; Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993) 159-208; Forrest McDonald, Alexander Hamilton: A Biography (New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company, 1979), 175-87; Edward M. Riley, “Philadelphia, The Nation’s Capital, 1790-1800,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 20, no. 4 (1953): 357-79.

[37] Fenno to Ward, December 18, 1793, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 2:188.

[38] Fenno to Ward, September 9, 1793, October 10, 1793, October 24, 1793, in ibid., 1:173, 178, 182.

[39] Fenno to Alexander Hamilton, November 9, 1793, in Harold C. Syrett, ed., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vols. (New York, NY: Columbia University, 1961-1987) 15:393-94.

[40] Hamilton to Rufus King, November 11, 1798, in ibid., 15: 395-96.

[41] For a remarkable treatment of Benjamin Franklin’s journey, see David Waldstreicher, Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004).

[42] Fenno to Ward, November 28, 1789, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1:348.

[43] J.H. Powell, Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993); J.R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[44] Fenno to Ward, August 30, 1798, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 2: 227-28.

[45] Pasley, Tyranny of Printers, 101-102.

[46] Fenno to Ward, August 30, 1798, , in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 2: 227-28.

[47] Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism (New York, NY: Public Affairs, 2006), 364-65; Pasley, Tyranny of Printers, 101-102.

[48] Gazette of the United States, September 17, 1798.

[49] See George Washington to the President of Congress, September 17, 1787, in W.W. Abbott, ed., The Papers of George Washington: Confederation Series, 5 vols. (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1992 -1997), 5:330-33; Catherine Drinker Bowen. Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitution: May to September, 1787 (New York, NY: American Past, 1966), 262-63.

[50] John Fenno not only published partisan attacks on his opponents in his paper, he also (as did other party printers) hurled verbal insults and debated rivals in public. See Burns, Infamous Scribblers, 335-36.

[51] New Hampshire Gazette, Sep 25, 1798; See also Federal Gazette and Baltimore Daily, September 18, 1798.

[52] For secular fame or immortality, see Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, no. 72, in Clinton Rossiter, ed., The Federalist Papers: Hamilton, Madison, Jay (New York, NY: New American Library, 1961), 437.

[53] For more on change and transformation in Ovid’s work, see Gareth Williams, On Ovid’s Metamorphoses (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2023).

[54] Fenno to Ward, January 10, 1790, in Hench, “Letters of Fenno” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1:354.

One thought on ““What Magic There is in Some Words!”: John Fenno’s Private Crusade for an American National Identity”

Good morning, Dr. McGhee, thank you, so much for this article, and for your service an an educator in the Philadelphia area. Thank you for bringing the Patriot John Fenno to the awareness your readership. Oh how history seems to repeat itself. In New Jersey, the Ledger, the Times of Trenton, the South Jersey Times, have ceased with their print editions, and Hudson County’s only daily, the Jersey Journal has ceased both its print and online editions, for some of the same issues that John Fenno had to grapple with.