The Fourth of July celebration of 1831 was shaping up similarly to the ones Americans had been commemorating for over half a century. A sizable crowd squeezed into the Rotunda of the United States Capitol Building to hear lawyer and poet Francis Scott Key deliver an Independence Day oration. In Boston’s Park Street Church the children’s choir of the Boston Sabbath School Union performed a new hymn that would quickly join Key’s “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the liturgy of the American civic religion. The melody was an old standard, but with new lyrics written by Andover Theological Seminary student Samuel Francis Smith. Its title was “America (My Country, ‘Tis of Thee).” In nearby Quincy former president John Quincy Adams was giving an address to the people of his hometown. A young state senator named William H. Seward was speaking to an Independence Day crowd of his own in Syracuse, New York. Meanwhile, two hundred and fifty miles to the south, Manhattanites were eating, socializing, and picknicking on the nation’s fifty-fifth birthday when in the late afternoon news began spreading that America’s fifth president, James Monroe, had just died at his daughter and son-in-law’s house at 63 Prince Street.

For Americans celebrating the fifty-fifth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence James Monroe’s death must have brought a sense of déjà vu, or even Divine Providence; just five years previously Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson had themselves passed away on the Fourth of July, the fiftieth anniversary of the nation’s founding. What followed over the next several days was an outpouring of grief and public mourning across the nation for the late president. Monroe’s funeral was on July 7 in New York City. Nearly 100,000 New Yorkers by some estimates lined the funeral route, creating a line of mourners stretching some three miles.[1] This was in a city of just over 200,000.[2] After a public viewing of the coffin on the steps of City Hall accompanied by a speech from the president of Columbia College and then services at St. Paul’s Chapel of Trinity Church, James Monroe was laid to rest in New York City Marble Cemetery. Among those who assisted in the late president’s funeral were two of his oldest friends, John Trumbull and Richard Varick. Like Monroe, both had served under Commander-in-Chief George Washington during the American Revolutionary War. The war had been a transformational experience for all three men, who were in their twenties or even teens when the war broke out in 1775. Monroe went on to be a congressman, governor, and of course president; Trumbull, the so-called Painter of the Revolution; and Richard Varick, the mayor of New York City and later President of the New York State Society of the Cincinnati, a position he held from 1806 until his own death in late July 1831, just weeks after he and Trumbull buried their friend Monroe.

Richard Varick was born in Hackensack, New Jersey on March 25, 1753. The Varicks came from Old Dutch stock and his paternal grandfather Abraham Varick married Anna Bertholf on July 12, 1718. Abraham and Anna’s children included Johannes (John) Varick, who was born five year later. John Varick grew up and in 1749 took Janneke (Jane) Dey, a young woman too of Dutch lineage, as his wife.

Growing up in Hackensack young Richard probably knew little of the monumental events taking place around him. The French and Indian War began the year after he was was born. He turned ten in 1763, the year that conflict ended. He turned twelve three days after British authorities passed the Stamp Act of 1765. New Yorkers led by the Sons of Liberty protested the stamp taxes in New York City just twenty miles from Hackensack across the North River. Though the Stamp Act was revoked in 1766 the colonists equally hated the subsequent Townshend Acts. While these seismic events were taking place young Richard was growing up safely in the bosom of Hackensack’s tight-knit Dutch community. New Netherland had long ago given way to British authority, but the Dutch still very much held on to their religious, cultural, and linguistic traditions. Hackensack was a bucolic community of successful merchants and bountiful farmsteads. Richard was baptized in Hackensack’s Dutch Reformed Church. His father and mother, John and Jane, hired a private tutor to prepare Richard for a professional career. It was increasingly clear that rural New Jersey was too small for a young man of Varick’s gifts; in 1771 just after his eighteenth birthday, he moved to New York City to clerk for attorney John Morin Scott. It was a consequential decision and indicative of a trend that would continue for the rest of his life: Richard Varick had become the trusted underling and confidant of a powerful, well-respected figure.

John Morin Scott was one of the leading attorneys in the insular world of New York jurisprudence, comprised as it was of just a few dozen lawyers collaborating and competing in equal measure depending on the clients and workload at any given moment. Scott was one of the “New York triumvirate” that included his good friends Williams Smith Jr. and William Livingston. The life of a young law clerk in British colonial New York was not glamorous. It entailed long hours of drudge work drafting wills, copying court briefs, and doing whatever mundane tasks might need to be done in a busy office such as Scott’s. This was on top of studying British law and preparing for the time when one might strike out on one’s own. Varick’s studies almost certainly included Commentaries on the Laws of England, the four-volume opus by Sir William Blackstone published in England between 1765 and 1769 and available by private subscription in the early 1770s from Philadelphia printer Robert Bell. Varick was licensed to practice law in October 1774 and became a partner in his mentor’s firm.

In the meantime, colonial politics were becoming more tense. In April 1774, shortly after Richard Varick’s twenty-first birthday and as he was preparing to assume his place as a fully-licensed attorney, New York had its own “tea party” when two ships carrying the imported product arrived off Sandy Hook. One returned to London with its shipment still on board, and the other had its contents thrown into the water. Alexander McDougall and the Sons of Liberty were integral to these acts of disobedience. The subsequent months saw the creation of committees of correspondence, assembly of the Continental Congress, and other activities as tensions between the colonies and Great Britain escalated.

Watching these and other events with great interest—indeed often playing a hand in them—were John Morin Scott, his young protégé Richard Varick, and the many prominent figures the two successful law partners knew. Varick’s military career began on June 28, 1775, soon after the creation of the Continental Army, when the Second Continental Congress commissioned him a captain. Varick was assigned command of the 6th Company of the 1st New York Regiment. Leadership of the 1st New York’s 2nd Company was given to Marinus Willett, himself a Varick family descendant and thus relative of Richard. Alexander McDougall, who had been a privateer during the French and Indian War and active in the Sons of Liberty going back nearly a decade, was appointed colonel of the 1st New York. Because of his involvement in the Provincial Congress McDougall understood the military and political situation well. In a testament to Varick’s rising reputation—and with the help of John Morin Scott—on July 1 he was also appointed secretary in Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler’s New York Department. Varick would also be the New York Department’s unofficial quartermaster, requisitioning any and all provisions that might be needed. Getting an army up to speed, let alone when facing the world’s leading superpower, was no easy task. Not only was there the recruiting and conscripting of men to consider, but the procurement of uniforms, shoes, forage for draft animals, food for men, guns, gunpowder, and myriad other accoutrements of war to requisition. All of this and more Richard Varick would help do under the commands of McDougall and Schuyler.

Major General Schuyler and Captain Varick boarded a transport ship on the North River and landed in the general’s hometown of Albany on July 9, 1775.[3] Because an invasion of Canada was a priority and the recently-captured Fort Ticonderoga a natural jumping-off point in making that happen, the general and his secretary quickly made their way to that stronghold. Schuyler wrote to Washington on July 18 to inform the commander-in-chief of his arrival at Fort Ticonderoga.[4] Soon joining them would be Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery. That summer Schuyler prepared a two-pronged offensive into Canada. The attack began well with the rebels taking Montreal but ultimately failed at the gates of Quebec, where Montgomery was killed on December 31, 1775.

Captain Varick remained in Upstate New York working his dual roles in the 1st New York Regiment and the New York Department. There were many tasks to keep the young officer—still just in his early twenties—busy in Albany, Fort Ticonderoga, and vicinity. While the war raged around New York City in the second half of 1776, things continued in Upstate New York. Varick wrote to Commander-in-Chief Washington resigning from the 1st New York Regiment on September 14.[5] His duties nonetheless expanded when the Continental Congress appointed him Deputy Muster Master General of the Northern Army eleven days later. This job primarily entailed keeping track of units and individuals within the New York Department and preparing muster rolls to ensure troop readiness and payment of wages. The Continental Congress further codified that position with the creation of the Muster Department on April 4, 1777. Congress confirmed Varick in the deputy muster master general title on April 10 and promoted him to lieutenant colonel. His position kept him away from the battlefield, but he did witness the British capitulation at Saratoga in October 1777.[6]

Lieutenant Colonel Varick carried on after surrender at Saratoga. His war changed when on January 12, 1780 the Continental Congress abolished the Muster Department and discharged its officers. Upon getting the news Varick returned to New Jersey. For a time he served light duty in the Bergen County Militia, commanded by his uncle, Col. Theunis Dey. Varick used his down time to brush up on the law. This was wise given that on April 9, 1779 New Jersey governor William Livingston, the friend of Richard Varick’s mentor John Morin Scott, had appointed him a state solicitor and counsellor, which meant Richard Varick was now licensed to practice law in both New York and New Jersey. The war remained ever present with a strong British and Hessian presence in the area carrying out offensive operations. In response Commander-in-Chief Washington established his headquarters at the home of Colonel Dey throughout July 1780.

On August 13 Richard Varick became an aide-de-camp to one of George Washington’s most trusted officers, Benedict Arnold. Arnold had performed well in the patriot cause since helping take Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775 and then more recently at Saratoga. Now he commanded West Point, headquartering himself at the Beverly Robinson House across the North River. In August and September Varick and others began whispering that Arnold was acting strangely. For one thing the general had been spending time in the company of British Maj. John André at the home of Joshua Hett Smith, the younger brother of John Morin Scott’s colleague William Smith Jr.

When Arnold’s treason came to light his aides’ fidelity too came into question. Varick was briefly detained, and though quickly released fell under a cloud of suspicion. Varick was ill throughout the Arnold affair and demanded a court of inquiry to exonerate himself. On October 12 he wrote to George Washington, “I have the Honor to inform Your Excellency, That I think my Health is so far restored, as to enable me to bear the Fatigue incident to an Attendance on a Court of Enquiry into my Conduct, which Your Excellency was so indulgent as to promise Me, as soon as I should be able to attend to It.”[7] The inquiry began at Robinson House on November 2, 1780. Varick testified on his own behalf. Read into the records too were depositions that Varick had solicited from supporters, including Philip Schuyler. Varick was exonerated and his reputation cleared on November 5. Still without a staff position, he practiced law in New York State in the succeeding months.

Washington kept meticulous records, and copious amounts of paperwork passed through his headquarters. The correspondence was voluminous and getting further out of hand. On April 4, 1781, just as the war was entering its seventh year, Washington wrote to Samuel Huntington, president of the Continental Congress, regarding his papers and averred that “Unless a set of Writers are employed for the sole purpose of recording them it will not be in my power to accomplish this necessary Work, and equally impracticable perhaps to preserve [them] from injury and loss.”[8] Washington continued that organizing the papers “must be done under the Inspection of a Man of character in whom entire confidence can be placed, and who is capable of arranging the papers, and methodizing the register.”[9] Congress quickly agreed to Washington’s request, and on May 25 Washington offered Lieutenant Colonel Varick the position of recording secretary. He began in July 1781. In this capacity Varick was in a genuine sense one of the first historians of the American Revolutionary War. He spent the final two and a half years of the war primarily in Poughkeepsie overseeing a staff of approximately half a dozen in transcribing, collating and organizing the backlog of letters, orders, and communiqués on topics large and small that poured to and from Washington’s headquarters.

Varick and his staff continued their work through the British surrender at Yorktown and the conclusion of the Treaty of Paris two years later. Washington bade farewell to his officers, resigned his commission and returned to Mount Vernon in December 1783—the same month Varick completed Washington’s papers.

On New Years Day 1784 Washington wrote to Varick expressing his appreciation:

The public and other Papers which were committed to your charge, and the Books in which they have been recorded under your inspection, having come safe to hand, I take this first opportunity of signifying my entire approbation of the manner in which you have executed the important duties of recording Secretary, and the satisfaction I feel in having my Papers so properly arranged, & so correctly recorded—and beg you will accept my thanks for the care and attention which you have given to this business.[10]

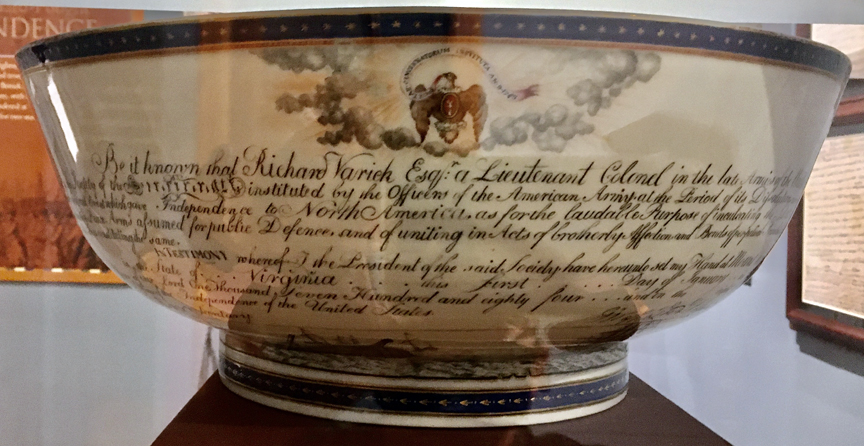

Washington also signed Varick’s Society of the Cincinnati membership diploma in his capacity as the organization’s president general. The membership certificate clearly meant a lot to Varick; shortly after its issuance, the diploma was printed on an exquisite porcelain bowl in China.

Richard Varick had spent his formative twenties in the service of the patriot cause and was just thirty when the Revolutionary War ended. The New York City to which he returned had experienced two devastating fires during the war that had destroyed much of the city’s buildings and infrastructure. His mentor and friend John Morin Scott died on September 14, 1784. But amidst these challenges were opportunities. Varick held jobs of increasing responsibility rebuilding New York City and State. Positions he held at various times included member of the New York City Common Council, Recorder of the City, Speaker of the New York State Assembly, and New York State Attorney General. In 1786 New York State commissioned Varick and fellow attorney Samuel Jones to distill into a comprehensible digest the legal statutes still relevant and in use after more than a century under British rule. Varick and Jones spent two years on this project and for their work were each paid £400 per annum.[11] New York printer Hugh Gaine published “Laws of the State of New-York” in 1789.

The Confederation Congress moved to New York City in January 1785, making Manhattan the capital of the nation. That spring on May 8 Varick wedded Maria Roosevelt. In June and July 1788 his new father-in-law, Isaac Roosevelt, joined other Federalists such as James Duane, John Jay, Chancellor Robert R. Livingston and Alexander Hamilton in ratifying the United States Constitution at the state convention in Poughkeepsie.

When New York mayor James Duane accepted a federal judgeship, Governor George Clinton appointed Richard Varick his successor. He began the mayoralty on October 14, 1789. Mayor Varick wrote to Vice President John Adams on July 21, 1790 to inform his that “The Corporation of this City have applied to the President of the United States to permit Colo. John Trumbull take his Portrait to be placed in the City Hall, to which the President has consented.”[12] Mayor Varick soon commissioned Trumbull for a portrait of Revolutionary War general and current New York governor George Clinton. Trumbull was the perfect choice, having served on Washington’s staff during the war and just returned from studying art in Europe. Like the mayor, governor, and president he was also a member of the Society of the Cincinnati. Trumbull duly finished the paintings, portraying Washington and Clinton not as the civic leaders they now were but as the Revolutionary War military officers they once had been. The national government left New York City in August 1790, after which Federal Hall again became New York City Hall. At an April 30, 1792 meeting of the Common Council Mayor Varick and the municipal legislature approved an expenditure of £135 for frames in which to properly exhibit Trumbull’s portraits of Washington and Clinton.[13]

In the 1790s New York City experienced rapid economic development and nearly doubled its population to over 60,000 as New Yorkers rebuilt their city.[14] There were also many episodes related to unfinished business from the War of Independence. Events that took place during Mayor Varick’s tenure included unrest over the controversial Jay Treaty, which Varick as a Federalist supported, and the Citizen Genêt Affair. When Thomas Jefferson became president he and his allies cleaned house. On August 24, 1801 Varick was replaced by the Democratic-Republican Edward Livingston.

Richard Varick remained active in banking, philanthropy, and real estate. Among much else he was a founder of Jersey City, chairman of the Board of Trustees of Columbia College, and later president of the American Bible Society. He and Maria purchased a summer home directly across the North River called Prospect Hall. Still, the Varicks remained Manhattanites. In 1806 Richard Varick became president of the New York State Society of the Cincinnati.

After the War of 1812 there was increasing talk of exhuming Gen. Richard Montgomery in Quebec and reinterring him in New York City. At a July 4, 1818 New York State Society of the Cincinnati meeting chapter president Varick read a letter from governor and Cincinnati member De Witt Clinton expressing support for this project. A committee comprising John Trumbull and others was granted “unlimited powers, to make the necessary arrangements for paying the last Tribute of respect to the remains of that distinguished hero of the Revolution.”[15] Two days later Janet Montgomery stood on the porch of her Hudson Valley home and watched the Richmond sail southward carrying the remains of her husband. The widow of forty-three years fainted dead away.[16] When Richard Montgomery was reinterred at St. Paul’s Chapel on Lower Broadway on July 8, 1818, Richard Varick, Marinus Willett, and John Trumbull were among the pallbearers.

The conclusion of the War of 1812 had ushered in the so-called Era of Good Feelings. From 1815 to 1825 Americans negotiated the Missouri Compromise, expanded the number of states in the union to twenty-four, and built the Erie Canal. Americans were feeling confident. This was the milieu in which President James Monroe and Congress invited the Marquis de LaFayette to visit the United States for a grand tour. In August 1824 the Frenchman sailed into New York for what would be a whirlwind thirteen months through all twenty-four states. On September 6, 1824 Richard Varick and the New York State Society of the Cincinnati hosted a fête in honor of Lafayette’s sixty-seventh birthday.[17] Varick next hosted LaFayette at Prospect Hall and saw him off on his journey. A triumphant LaFayette returned to New York City for rest and revelry in July 1825, which included a trip across the river to Prospect Hall on July 9, 1825 for some quiet time with his old friend.[18] The French dignitary sailed home from Washington D.C. on September 9. In the ensuing years as Americans celebrated the 1826 Jubilee and entered the Jacksonian era Richard Varick entered the winter of his life. Many he had once known were gone and he was becoming increasingly rueful. In May 1831 he visited Mount Vernon, still a private residence owned by the Washington family.[19] Varick was declining quickly by the time of James Monroe’s funeral on July 7.

On August 1, 1831 former New York City mayor and diarist Philip Hone wrote that

Col. Richard Varick died on Saturday night [July 30] at his residence, Jersey City, in the seventy-ninth year of his age, of cholera morbus. . . . Measures are taking to pay great respect to his memory. General orders are issued for the Division of Artillery. The Society of the Cincinnati have announced his death, and the order of the funeral ceremonies under direction of Gen. Morgan Lewis, vice-president. Both houses of the Common Council and the Court of Sessions, which were sitting, adjourned this morning on the announcement of his death.[20]

John Trumbull, Peter Augustus Jay, the eldest son of John Jay, and Nicholas Fish, with whom Varick had clerked in the office of their mentor John Morin Scott were among the pallbearers. Richard Varick rests today in the cemetery of Hackensack’s First Dutch Reformed Church. Maria received a Revolutionary War pension of $600 per annum under Congressional legislation passed in 1838 granting benefits to widows who had married veterans prior to January 1, 1794.[21] She died in 1841 and lies today beside Richard.

If New Yorkers know Richard Varick today it is for a street bearing his name in Lower Manhattan. Several factors partly explain why Richard Varick is so little known. These include the fact that he and Maria had no children to promote his legacy; his Dutch and not English heritage; and a tendency to view Varick as a supporting, not primary, figure in the American Revolution.

Very little remains of Richard Varick’s New York but much of the iconography and material culture that he helped create survives today. The city hall in which Varick presided was torn down in the 1810s after the completion of a new municipal building a few blocks north. The Trumbull portraits of Washington and Clinton that Mayor Varick commissioned were relocated to the new edifice and have hung in the Governor’s Room there for over two centuries. Beside them stands a likeness of Varick done by the same artist. These works are part of what is one of the most important collections of Early American art in the nation. The extended family of Deys and Varicks inherited many of Richard and Maria’s personal effects, eventually giving them to several leading institutions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Renderings of Richard Varick reside in the collections of the Albany Institute of History and Art, the American Bible Society in Philadelphia, the Society of the Cincinnati’s Anderson House national headquarters in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. The Chinese porcelain Society of the Cincinnati bowl dating back to the mid-1780s, one of the finest of its kind, is on public view at Morristown National Historical Park. Scholars themselves owe Richard Varick a huge debt for the work he did in the war’s final two and a half years on George Washington’s papers. What are now called the Varick Transcripts remained in the Washington family until 1834, when Congress purchased a portion of them.[22] In 1849 Congress bought the remainder.[23] The Department of State managed the Varick Transcripts until June 29, 1904, when the full set was transferred to the Library of Congress.[24] There they remain today, an invaluable resource for generations of historians.

Richard Varick was a man of Dutch lineage born in British Colonial New York who eventually became an American. Coming of age amidst great events, he was fortunate seemingly always to meet the right person at the right moment that created the greatest benefit for himself and his associates. He began as a colonial lawyer who left a promising civilian career to serve as a Continental Army officer in a revolution that easily could have ended in failure. Once independence came, Varick helped codify New York State jurisprudence for a new era. Then, he put his experience as a civil servant to use in his tenure as New York City mayor over twelve exciting and challenging years. He also served the public good through his charitable work and efforts at creating a usable past and American iconography. In so doing Varick stewarded the creation of not just modern New York City and State, but the United States of America itself.

[1] Louis L. Picone, The Presidents is Dead!: The Extraordinary Stories of the Presidential Deaths, Finals Days, Burials, and Beyond (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016), 30.

[2] Department of Commerce and Labor, “Population: New York City. Number of Inhabitants, by Enumeration Districts,” Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Bulletins (Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, 1910), 2.

[3] Don R. Gerlach, Proud Patriot: Philip Schuyler and the War of Independence, 1775-1783 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1987), 19.

[4] Philip Schuyler to George Washington, July 18, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0076.

[5] Peter Force, ed., American Archives: Consisting of a Collection of Authentick Records, State Papers, Debates, and Letters and Other Notices of Publick Affairs, the Whole Forming a Documentary History of the Origin and Progress of the North American Colonies, series 5, vol. 2 (Washington: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1851), series 5, vol. 2:335.

[6] Paul Cushman, Richard Varick, A Forgotten Founding Father: Revolutionary War Soldier, Federalist Politician & Mayor of New York (Amherst, MA: Modern Memoirs Publishing, 2010), 56-57.

[7] Richard Varick to Washington, October 12, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-28-02-0192-0016.

[8] John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, n.d.), 21:411-412.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Washington to Varick, January 1, 1784, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0002.

[11] Samuel Seabury, “Samuel Jones, New York’s First Comptroller,” New York History 28, no. 4 (October 1947): 400.

[12] Varick to John Adams, July 21, 1790, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-20-02-0229.

[13] A. Everett Peterson, ed., Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784-1831, vol. 1, February 10, 1784-April 2, 1793 (New York: City of New York, 1917), 710.

[14] Department of Commerce and Labor, “Population: New York City,” 2.

[15] John Schuyler, Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati (New York: Printed for the Society by Douglas Taylor, 1886), 104-105.

[16] Louise Livingston Hunt, “General Richard Montgomery,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 70, no. 417 (February 1885): 358.

[17] Schuyler, Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati, 106.

[18] J. Bennett Nolan, Lafayette in America, Day by Day (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1934), 296.

[19] Arthur S. Lefkowitz, George Washington’s Indispensable Men: The 32 Aides-de-Camp Who Helped Win American Independence (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003), 225.

[20] Bayard Tuckerman, ed., The Diary of Philip Hone 1828-1851, vol. 1 (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1889), 1:33-34.

[21] Jack D. Warren, Jr., America’s First Veterans (Washington, DC: The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati, 2020), 142.

[22] Dorothy S. Eaton, “Introduction,” Index to the George Washington Papers (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1964), xiii.

[23] Ibid., xv.

[24] Ibid., xvi.

2 Comments

Thoroughly enjoyed this article.

Great article about someone that was in the shadows conducting very important business throughout the war. I have always thought Varick was with General Arnold in their escape from Canada?