I recently came across the recollections of Simeon Thayer, who served from 1777 to 1781 as a major in Rhode Island Continental Army regiments. He was one of the outstanding military figures from Rhode Island during the war.

His recollections start with him as a teenager during the French and Indian War serving in Maj. Robert Roger’s ranger corps, engaging in battles in the forests with Indian enemies. He barely survived becoming a prisoner at the infamous surrender of the British garrison at Fort William Henry. He moved from Mendon, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island, where he apprenticed as a wigmaker. Prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, he was selected as an officer of an independent regiment in Providence and the Rhode Island General Assembly later appointed him as a captain in a Rhode Island regiment. He served in that capacity on Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Quebec, enduring the incredible hardships of the wilderness crossing of Maine forests. After the failed attempt to seize Quebec, he became a prisoner of the British. His journal is one of the key original sources for the remarkable expedition.[1]

After being exchanged in 1777, Thayer was appointed major in the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment. He served at the defense of Fort Mercer at Red Bank in New Jersey. Immediately afterwards, he assumed command of Fort Mifflin, which stood on the opposite side of the Delaware River from Fort Mercer. In 1778 at Barren Hill outside Valley Forge, he commanded a rear guard protecting the main division under the Marquis de Lafayette; Thayer was also able to bring his rear guard to safety, escaping great danger from a larger enemy force. Thayer was wounded at the Battle of Monmouth after a cannonball rushed so close to his left eye that it made it bleed; the wound adversely affected his health for the remainder of his life. Thayer also served at the Battle of Springfield in 1780, when the 2nd Rhode Island made a courageous stand defending a bridge against superior enemy forces.[2]

After studying the Battle of Red Bank recently, I realized that his recollections tied together some loose strands that have not been adequately addressed in prior histories of the battle. The Battle of Red Bank was one of the most surprising and one-sided American victories of the war. General Washington was thrilled about it, because it was one of the few American successes in the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777.

On October 22, 1777, more than 1,200 German soldiers under Col. Count Carl Emil von Donop attempted to storm Fort Mercer, located on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River, and failed disastrously. The fort was defended mainly by some 350 rank-and-file soldiers who were present and fit for duty from the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments. A company of Continental artillerymen under Capt. David Cook, with about sixty-three officers and men present and fit for duty, assisted in the defense. Col. Christopher Greene, the commander of the 1st Rhode Island, also commanded the fort’s garrison.[3]

Simeon Thayer wrote of Red Bank:

Here I was detached the morning after my arrival 10th of October with 150 men to join Col. Smith [Samuel Smith of Maryland] on Mud Island when the enemy’s batteries were laying there. I continued three days [at Fort Mifflin] when the Hessians appeared as if they intended an attack on Red Bank. I then received an extract from Col. Greene to return military troops to Red Bank about 12 o’clock, which I immediately complied with and reached the fort just as the Hessians appeared in sight.[4]

Thayer highlighted an important, but previously ignored and not fully understood, part of the battle. How was it that he was in charge of 150 officers and soldiers at Fort Mifflin when Fort Mercer was about to be assaulted by a superior enemy force? Over the years, I have realized that unless the researcher asks the question, the researcher is not likely to find the answer.

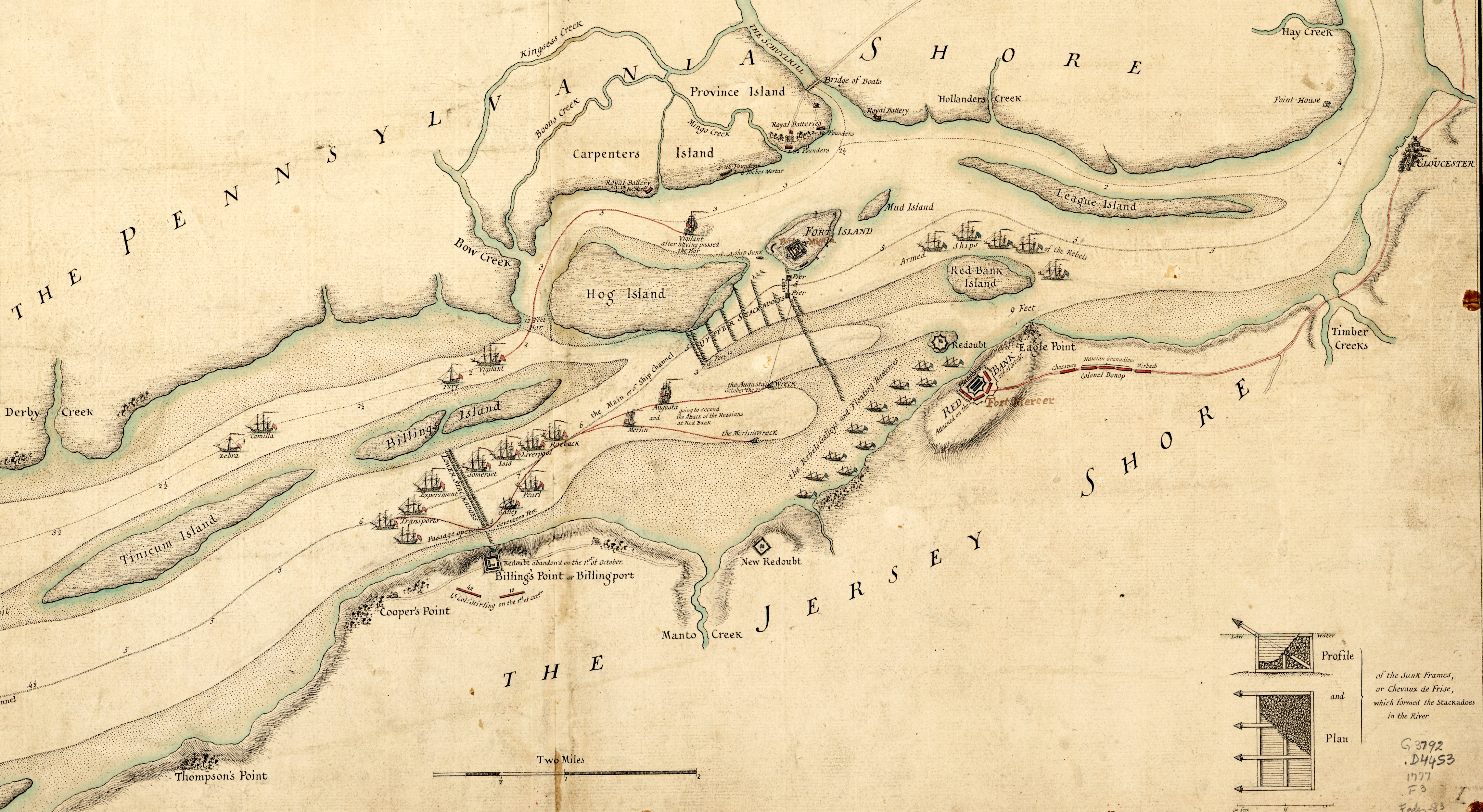

The story starts with the Philadelphia Campaign of September and October 1777. British Gen. William Howe had soundly defeated the largest army Washington would ever command at Brandywine, allowing Howe on September 26 to seize the capital of the new United States, Philadelphia. Then Howe was able to beat back a strong counterattack by Washington’s main army at the Battle of Germantown on October 4. Now Washington hoped to starve out the British by holding two key forts below the city on opposite sides of the Delaware River, Fort Mercer and Fort Mifflin. Washington sought to prevent supply ships from safely reaching Philadelphia upriver.

On October 8, General Washington issued an order to Colonel Greene to march his 1st Rhode Island Regiment, as well as the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment commanded by Col. Israel Angell, to Fort Mercer.[5] Both regiments had just marched from the Hudson Highlands and were about to join the main Continental Army at Pennypacker’s Mills. In his instructions that followed, Washington showed surprising desperation:

Upon the whole Sir, you will be pleased to remember that the post with which you are now entrusted is of the utmost importance to America, and demands every exertion you are capable of, for its security and defense. The whole defense of the Delaware absolutely depends on it, and consequently all the enemy’s hopes of keeping Philadelphia, and finally succeeding in the object of the present campaign. Influenced by these considerations, I doubt not your regard to the service and your own reputation, will prompt you to every possible effort to accomplish the important end of your trust and frustrate the intentions of the enemy.[6]

On October 9, Washington received new intelligence causing him to modify is orders. He ordered Greene to send the 2nd Rhode Island to join Gen. James Varnum’s brigade with the main army.[7] Greene grudgingly complied with the order, but when he arrived at Fort Mercer late on October 11, he realized the fort was too extensive for his single regiment to defend. On October 14, he sent Washington a letter requesting that the 2nd Rhode Island join him at Fort Mercer.[8]

Washington at the time was most worried about retaining Fort Mifflin. In early October, the Royal Navy tried to bomb that fort into submission. Spiked wooden log obstructions called chevaux-de-frise placed in the channel by the Americans, as well as a Pennsylvania Navy fleet of small boats commanded by John Hazelwood, helped defend against a water-borne attack. The American commander at Fort Mifflin, Lt. Col. Samuel Smith of Maryland, held firm.

On October 14, Washington issued orders to Colonel Greene “to send sufficient men to replace deserters in Commodore John Hazelwood’s fleet and to assist Lieutenant Colonel Smith.”[9] Washington explained the next day: “I am persuaded by intelligence from different quarters that the enemy are determined to endeavour by a speedy and vigorous effort to carry Fort Mifflin, and for this purpose are preparing a considerable force.” Noting that his view that Colonel Smith’s force at Fort Mifflin “is not as great as could be wished and requires to be augmented,” Washington ordered Greene “to detach immediately as large a part of your force as you possibly can in aid of his garrison.”[10]

Washington also ordered Colonel Angell to march his regiment the next morning, October 15, to reinforce Fort Mercer.[11] While this move pleased Greene, he must have not been happy to reduce his force of defenders at Fort Mercer.

In the morning of October 15, Greene issued orders for a lieutenant, a sergeant and twenty men to march to Fort Mercer to “work at Fort Mifflin under the direction of Colo. Smith.”[12] Those soldiers likely were immediately ferried across the river to Fort Mifflin. This was a small reinforcement from his own regiment, but Greene must have determined it was all he could spare.

In the same afternoon, Greene changed his mind. Knowing that the 2nd Rhode Island would soon be arriving at Fort Mercer, he increased the size of the detachment from his regiment sent to Fort Mifflin. That afternoon, Greene issued an garrison order for “Two captains, six subalterns and one hundred rank-and-file with pieces of cannon to parade in the Fort at five o’clock this afternoon with their arms, accoutrements and blankets, to be commanded by Col. Hand who will receive his orders from the commanding officer of the garrison.”[13] Greene no doubt instructed Col. Edward Hand to reinforce Fort Mifflin.

Sergeant John Smith of the 1st Rhode Island kept a diary during this time. For October 15, he wrote in part, “that night the whole of Colo. Greene’s Regiment off duty was detached to Fort Mifflin—officers, waiters, none excepted, about 1020.”[14] Smith was not part of this detachment. The transcriber of Smith’s valuable diary, Bob McDonald, wrote of this entry, “This figure [1,020] is far in excess of the total strength of the First Rhode Island Regiment. Its citation by Smith is unexplainable.”[15] The number should be read as 120, consistent with Greene’s garrison orders quoted in the above paragraph. In the original manuscript held by the American Antiquarian Society, I detected a half-line through the first 0, indicating an intent to make the number 120.

In a weekly return of the 1st Rhode Island dated October 17, 1777, 123 rank-and-file are listed as “on command.”[16] When a soldier was “on command,” it meant that the soldier was away from the regiment’s main camp engaging in various military duties. Typically, in a weekly return for this regiment, no more than around 25 rank-and-file in the regiment were “on command.” So, the number of 123 rank-and-file soldiers was surprising. These soldiers must have formed the two detachments from his own regiment that Greene had sent to Fort Mifflin.

In the evening of October 18, after marching some sixty miles without sleep, Colonel Angell and the men of his regiment arrived at Fort Mercer.[17]

The next day, Greene issued the following “Garrison” order: “Major Simeon Thayer with 3 C. [captains]), 9 S. [subalterns], 12 S. [sergeants], 4 Df [drummers and fifers], and 121 rank-and-file” from Colonel Angell’s Regiment to muster in the fort at 3 p.m. to relieve a detachment from Colo. Greene’s Regiment at Fort Mifflin.[18] Here was the information I was seeking. Major Thayer was sent this day to Fort Mifflin, in command of a total of 121 rank-and-file; combined with the officers and non-commissioned officers, the detachment totaled almost 150 men, consistent with Thayer’s recollection.

Unknown to Washington, Howe was getting frustrated with the difficulty in getting at Fort Mifflin and with its tenacious defense. On October 21, he ordered Colonel von Donop to march more than 2,200 Hessian troops from Philadelphia to take Fort Mercer.

What we then learn from Thayer’s recollections is that after spending three days at Fort Mifflin, as the fort continued to suffer a heavy bombardment from Royal Navy warships, at about noon on October 22 Thayer received orders from Colonel Greene to return to Fort Mercer with his detachment. Thayer and his men were ferried across the Delaware River. We also learn from Thayer that he and his troops arrived back at Fort Mercer “just as the Hessians appeared in sight” outside Fort Mercer.

Jeremiah Greenman, who kept a diary for most of the war during his service with the 2nd Rhode Island, was a sergeant with the detachment at Fort Mifflin. His diary does not indicate when he arrived there, which must have confused some historians. But he was there. For October 21 he wrote, “Continuing at Fort Mifflin, the duty very hard indeed.” His diary entry for October 22 indicates that in the morning Major Thayer was informed that an enemy force was on its way to attack and that the 2nd Rhode Island men were then ferried back across to Fort Mercer. His detachment, Greenman continued, “had scarce an opportunity to get into the fort [Fort Mercer] before a flag came to Colo. Greene.” [19]

Two diary entries confirm that Greene received intelligence the evening of October 21 that a Hessian force under von Donop was on its way, giving Greene time to send orders for Thayer to return to Fort Mercer.[20] In his diary entry for October 22, Colonel Angell further wrote that at about 1 p.m., “the enemy arrived within musket shot of our fort.” About 4:00 p.m. on October 22, enemy officers approached Fort Mercer with a white flag and insisted that the defenders surrender the fort or the attackers would give no quarter; the demand was firmly rejected. At 4:30 p.m., the German troops began a bombardment of the fort as a precursor to attempting to storm it.[21] Thus, it appears that Major Thayer’s detachment must have arrived at Fort Mercer around 3:30 p.m.[22]

With so much activity and action occurring on the morning and afternoon of October 22, the eyewitness diarists and correspondents who later described the action at the battle (other than Jeremiah Greenman who has an obscure reference) do not expressly mention the arrival of the 150 officers and men under Major Thayer at Fort Mercer just before the assault started.[23] Still, it was fortunate that Thayer and his large detachment arrived in time to defend against the attempted storming. They represented more than one third of the rank-and-file Continental infantrymen defending the fort.

The defenders routed the attackers, who fled the field of battle leaving many of their dead and wounded behind. The losses of the Germans were about 90 dead, 227 wounded, and 69 missing or taken prisoner. The American defenders suffered only about fourteen killed, and from 23 to 27 wounded. Historian Dr. Robert Selig called the failed assault the Hessians’ “worst defeat of the war.”[24]

In his recollections, Thayer then provided information on how Count von Donop, mortally wounded in the assault, was located and surrendered. Thayer’s recollections here are the most reliable source for this incident. Thayer recalled that “after the enemy had departed” from Fort Mercer, many of the Hessian casualties were left behind. Thayer recalled further that he was:

detached . . . about the dusk of the evening with a small party to bring in the wounded. I was employed in this humane service, [when] two Hessian Grenadiers came and told me that their commanding officer Count Donop was lying wounded in the edge of the wood near where their artillery had played. As it was near dark, I suspected they might mean to decoy me into an ambush. I therefore ordered them under guard telling them if they deceived me, they should be immediately put to death to which they readily consented and conducted me to the place where I found the Count lying under a tree mortally wounded. He asked me if I was an officer and what rank, of which being satisfied he surrendered himself as a prisoner to me when I ordered six of my guard to take one of the Hessian blankets from his pack and carry him therein with all possible care to the fort where he was received by Col. Greene.[25]

Colonel Smith left Fort Mifflin on November 11 due to suffering a wound, and his replacement asked to leave claiming exhaustion. Thayer volunteered to command the post. It was a thankless task as everyone knew Fort Mifflin was about to fall. Thayer took command on November 12. The Royal Navy had been able to remove some obstructions in the river and its ships and the Royal Artillery from land began a bombardment on November 10 that was so intense that it can be described as a precursor to the artillery barrages of World War I. On November 16, Thayer issued orders for his men to abandon the fort; he was the last to leave. Jeremiah Greenman wrote in his diary that “Major Thayer evacuated the fort with a degree of firmness equal to the bravery of his defense” as “he set fire to the remains of the barracks and with less than two hundred men carried off all the wounded and most of the stores.”[26] In turn, realizing that Fort Mercer was indefensible without Fort Mifflin, Greene abandoned Fort Mercer on November 19 and 20.[27]

On November 4, the Continental Congress, meeting in York, Pennsylvania, awarded “an elegant sword” to Christopher Greene for the “gallant defence” of Fort Mercer and to Samuel Smith for the “gallant defence” of Fort Mifflin.[28] This was twelve days before Fort Mifflin was abandoned. Brig. Gen. James Varnum and other Rhode Islanders expressed disappointment that Major Simeon Thayer was not awarded the presentation sword rather than Smith.[29]

[1] See Capt. Simeon Thayer’s Journal, in Kenneth Roberts, ed., March to Quebec, Journal of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1938), 245-94.

[2] This summary is from Simeon Thayer, “A journal of the suffering of Simeon Thayer in the two last wars in America,” undated (circa 1790), Simeon Thayer Papers, Revolutionary War Papers, Mss 27, Box 1, Rhode Island Historical Society (“Simeon Thayer Recollections”). This is the longer of two versions of Thayer’s recollections in the same file.

[3] See Return of the Garrison at Red Bank, October 27, 1777, in George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, 1697-1799 MSS 44693, Reel 45, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. This return showed 172 rank-and-file in the 1st Rhode Island present and fit for duty and 168 in the 2nd. For all of the defenders, including Captain Cook’s Company of Artillery, the return showed a total of 534 officers and men present and fit for duty. However, this return was taken after the October 22, 1777, battle. Thus, at the time of the battle, the two regiments likely had a few more men than were counted after the battle on October 27—those who were killed or were seriously wounded. Accordingly, about 550 total defenders is a more accurate estimate. Including officers and non-commissioned officers, the totals in the Return of the Garrison were 244 for the 1st Rhode Island, 227 for the 2nd Rhode Island, and 63 for Captain Cook’s Company of Artillery, for a grand total of 534.

[4] Simeon Thayer’s Recollections.

[5] George Washington to Christopher Greene, October 8, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0305.

[6] Instructions to Colonel Christopher Greene, October 8, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0453.

[7] Washington to Greene, October 9, 1777, ibid., founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0470; Greene to Washington, October 10, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0481.

[8] Greene to Washington, October 14, 1777, October 14, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0512.

[9] Washington to Greene, October 14, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0310.

[10] Washington to Greene, October 15, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0525.

[11] George Washington’s aide-de-camp, Tench Tilghman, wrote Brig. Gen. Silas Newcomb of the New Jersey militia at 10 p.m. on October 14 that Colonel Greene “has orders to send the greatest part of his force to Fort Mifflin” and that “Colo. Angell will march from hence tomorrow morning with another regiment of Continental troops to reinforce you” at Fort Mercer. Quoted in ibid., note 1. See also diary entry, October 15, 1777, in Joseph Lee Boyle, ed., “The Israel Angell Diary, 1 October 1777-28 February 1778,” Rhode Island History, vol. 58, no. 4 (November 2000), 112 (Angell received orders in late afternoon to march at 7 a.m. for Fort Mercer).

[12] Garrison Orders, October 15, 1777, in 1st Rhode Island Regimental Orderly Book, Christopher Greene Papers, Mss 455, Box 1, Volume 2, Rhode Island Historical Society.

[13] Garrison Orders, October 17, 1777, in ibid.

[14] Diary entry, October 15, 1777, in Sergeant John Smith Diary, American Antiquarian Society, transcription by Bob McDonald, accessed at revwar75.com/library/bob/smith2.htm (“John Smith’s Diary”).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Weekly Return, October 17, 1777, in Weekly Returns, Enlistments, Casualties Book for the First Rhode Island Regiment and Rhode Island Regiment, Revolutionary War Papers, Mss 673, Subgroup 2, Series 1, SS-A, Box 1, Folder 60, Rhode Island Historical Society.

[17] Diary entry, October 18, 1777, in Boyle, ed., “Israel Angell Diary,” 112; see also diary entry, October 18, 1777, in John Smith’s Diary. Thayer incorrectly recalled that the 2nd Rhode Island arrived at Fort Mercer on October 10.

[18] Garrison Orders, October 19, 1777, in First Rhode Island Regimental Orderly Book.

[19] Jeremiah Greenman diary entries, October 21-22, in Robert Bray and Paul Bushnell, eds., Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (DeKalb, IL: Northern University Press, 1978), 80. Historian Thomas J. McGuire figured out Greenman’s reference, but he thought the detachment consisted of Angell’s entire regiment and he does not mention the garrison orders. See Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, Germantown and the Roads to Valley Forge (Lanham, MD: Stackpole Books, 2007), 159.

[20] Diary entry, October 21, 1777, in Boyle, ed., “Israel Angell Diary,” 113; diary entry, October 21, 1777, in Sergeant John Smith Diary, American Antiquarian Society, transcription by Bob McDonald, revwar75.com/library/bob/smith2.htm.

[21] Diary entry, October 22, 1777, in Boyle, ed., “Israel Angell Diary,” 113 and John Smith’s Diary.

[22] Sergeant John Smith has the following for October 21: “between 3 & 4 o’clock, 300 more troops came here to reinforce us.” John Smith’s Diary. This entry could be a reference to Thayer’s detachment arriving at Fort Merc around 3:30 pm the next day; if so, Smith had the wrong day.

[23] Jeremiah Greenman diary entry, October 22, in Bray and Bushnell, eds., Diary, 80.

[24] Robert A. Selig, African-Americans, the Rhode Island Regiments, and the Battle of Fort Red Bank, 22 October 1777, Draft Prepared for Gloucester County, New Jersey, 2019 (“Selig, Fort Red Bank Draft Report”). Provided by Dr. Selig to the author. The draft is no longer accessible online; Dr. Selig is finalizing his draft report, which will be accessible online. For descriptions of the battle and its aftermath, see ibid.; James McIntyre, A Most Gallant Resistance, The Delaware River Campaign, September-November 1777 (Point Pleasant, NJ: Winged Hussar, 2022), 130-33 and 149-72; McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, chapter 3.

[25] Simeon Thayer’s Recollections. I have changed the third person narrative here to the first person.

[26] Jeremiah Greenman diary entry, October 15, 1777, in Bray and Bushnell, eds., Diary, 86.

[27] Diary entries, November 15 and 19-20, 1777, in Boyle, ed., “Israel Angell Diary,” 116-17 and John Smith’s Diary.

[28] See Congressional Resolutions, November 4, 1777, in Chauncey Ford Worthington, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, vol. 9 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1907), 862. Commodore John Hazelwood was also awarded an honorary sword. Ibid. For more on the presentation swords, see Christian McBurney, “Presentation Swords for 10 Revolutionary War Heroes,” May 16, 2014, Journal of the American Revolution, allthingsliberty.com/2014/05/presentation-swords-for-ten-revolutionary-war-heroes/.

[29] See Letter to the Editor from James Varnum, Providence Gazette, August 5, 1786; Benjamin Cowell, Spirit of ’76 in Rhode Island (Boston: A. J. Wright, 1850), 295-304.

5 Comments

What an interesting piece in tying so many loose ends together. Red Bank is one battle where the Americans prevailed, but “detached duty” doesn’t pay in recognition of the work. Thayer did much with few

Christian, this is a captivating article backed up with impressive research! Surprisingly, the Hessians left their wounded commander on the battlefield. One would have thought his soldiers would have carried him off the field to receive aid despite his mortal wound. Also, the Hessian second in command did not arrange for care of the casualties, which seems strange as it was unlikely that the Americans would pursue the retreating Hessians. On the other hand, the fog of battle may have prevented clear thinking and decision-making.

A fine article about a great victory against the Hessians that reinforced lessons about American fighting men that they had learned earlier at Trenton and Princeton.

As the battle was going on, out in the river, the British 64-gun ship-of-the-line, Augusta. likely positioning herself to shell Fort Red Bank from the rear, exploded in a great ball of fire at about noon. Perhaps from a shell from the Pennsylvania navy gunboats or an accident. As she was rescuing survivers at about 3 pm, the sloop Merlin caught fire and had to be abandoned. A great victory for the defending Pennsylvania navy to accompany the Rhode Islanders.

As a result of these defenses on 22 Oct. and an noreaster, the British navy retreated to Chester and Fort Billingsport NJ, which they had captured. The assault on Fort Mifflin did not resume until mid-November. By then the fort had been reinforced again, but the British ships had been rearmed and brought a shallow draft gunship within point blank range of the wester land side of Fort Mifflin. The fort was evacuated to still-surviving Redbank.

Christian,

A fascinating read on battles I had little knowledge of. Always elated to read stories about fellow Rhode Islanders who prove their mettle and worthiness in battle.

Dan Hazard

There is a very detailed and lengthy (250 pages incl. 90 pages of transcripts of primary sources) account of this battle:

“It is Painful for Me to Lose so Many Good People”: Report of an Archeological Survey

at Red Bank Battlefield Park (Fort Mercer), National Park, Gloucester County,

New Jersey. Prepared for Gloucester County Department of Parks and

Recreation and the American Battlefield Protection Program. (West Chester,

Pennsylvania: Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., 2017). Together with Wade

P. Catts, Elisabeth Lavigne, Kevin Bradley, Kathryn Wood, and David G. Orr.

It is available on-line here:

https://www.gloucestercountynj.gov/DocumentCenter/View/959/Red-Bank- Battlefield-Archeology-Report-PDF?bidId=