June 9, 1776: The colonel and the preacher exchanged concerned glances as they crouched in the swamp. They were spattered in mud, exhausted, and cut off from their unit. Visibility was poor through the trees, but they could hear the crack of musket fire nearby . . . the enemy was getting close. They saw no way out, and had no idea what would happen to them if they were caught by the British.

* * *

As the American colonies and Britain careened into the American Revolutionary War, they faced a dilemma: how to handle prisoners of war. Both sides decided to adopt the tradition of parole, an honor-based system that kept captured officers out of the fighting. The story of two American officers captured together—Col. William Irvine and chaplain Daniel McCalla—illustrates the danger and challenges that parole could impose.

Parole was a promise between the two opposing sides, and a promise that obligated a soldier. The captor would release a prisoner of war “on parole” if the prisoner promised to live up to written obligations—usually a vow not take up arms or carry out military acts until he was formally released from parole through a prisoner exchange agreement. A paroled officer might enjoy a supervised or unsupervised “house arrest”: he could have freedom of movement within a limited area inside enemy territory, or be allowed to return to his army’s lines, or be asked to go home. By the seventeenth century, parole had become a customary practice in Europe.[1]

Parole was a practical solution. Housing, feeding, and providing medical care to prisoners taxed both sides’ resources. And each side was motivated to treat its prisoners decently, lest the other side exact retribution on the prisoners it held. The Americans had captured enough British officers and men in 1775 that the British army took a pragmatic approach and usually treated captured American officers as equals, with an attendant level of respect. Parole was regularly granted to officers because they were considered gentlemen who could be trusted to honor the terms. As historian Holger Hoock noted, “The conventions of gentlemanly warfare trumped concerns for secrecy and safety. . . . An officer violating the conditions of his parole risked having his privileges revoked and being put into close confinement.”[2] As the war progressed, some of the war’s most valuable officers were paroled and exchanged.[3]

But enlisted men were usually not so fortunate. Rather than enjoying parole, they tended to end up in prison, and often stayed there. George Washington was committed to treating British enlisted prisoners decently, but the British government did not have regard for common rebels, and thousands of American enlisted men began dying in British prison camps. As the war progressed, Congress became enraged at this, and embraced a policy of retribution.[4]

Against this background, Irvine and McCalla would find that the “honor system” of parole was hard to live within, and could be deeply unfair.

* * *

A Scots-Irish Presbyterian born in Ireland on November 3, 1741, William Irvine studied medicine in Dublin, served as a surgeon in the British navy during the French and Indian War, and then settled in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1764. There he practiced medicine, started a family with his wife Ann, and became known as a reserved and trustworthy man. Irvine also followed politics closely. On July 12, 1774 he organized Carlisle’s boycott of British goods as a protest of the Tea Act.[5] Later that month he was sent to the Provincial Convention in Philadelphia “held for the purpose of instructing the Assembly on the will of the people” as to whether to convene the First Continental Congress. The Pennsylvania Assembly granted Irvine a colonel’s commission in January 1776 to command the 6th Pennsylvania Battalion.[6] He was thirty-five years old, a socially connected and assured veteran.

Like Irvine, the Reverend Daniel McCalla was also a Scots-Irish Presbyterian. McCalla was born on July 23, 1748 in Neshaminy, Pennsylvania, twenty miles north of Philadelphia. He attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), a Presbyterian institution. McCalla absorbed the college’s classical curriculum eagerly, and studied with such intensity that he was asked to take a semester break to preserve his health. He graduated at the age of nineteen, with a reputation for scholarly attainment, and added medical studies and modern languages to his store of knowledge while he ran an academy in Philadelphia.[7] In 1772, he began preaching at the New Providence Presbyterian church outside Philadelphia and just north of Valley Forge, and was ordained on November 17, 1774.[8] Despite his scholarly nature, he was known as an eminently social person and an excellent speaker.

As the war began, McCalla became an ardent supporter of the colonial cause. “He became peculiarly useful, in directing the views, and inspiring the patriotism of many others,” reported his friend and biographer William Hollinshead.[9] Not content to merely preach independence, McCalla received leave from his congregation to serve in the Continental Army. On January 16, 1776 he was appointed by the provincial council of Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety to serve as a chaplain in the 1st Pennsylvania Battalion, which became Arthur St. Clair’s 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment.[10] McCalla’s duty would be to serve the spiritual needs of the men in his unit, and to inspire them in good times and bad.[11] The committee that appointed McCalla included Anthony Wayne, who had just been made colonel of the 4th Pennsylvania. McCalla was twenty-eight years old, full of passion for the cause, and without experiences that would prepare him for what came next.

* * *

The Continental Army had begun its invasion of Quebec in September 1775, hoping to evict the British from Canada and secure the colonies’ northern border. The operation had faltered, and in late April 1776, Washington ordered ten regiments to Canada as reinforcements. These included the Pennsylvania units under Colonels Irvine, Wayne, and St. Clair. The army was short of chaplains and McCalla was spread thin, caring for men across regiments.[12] They arrived in Canada in late May, and joined troops under the command of Brigadier General William Thompson. Thompson soon ordered the Pennsylvanians and Maxwell’s New Jersey regiment, about 2,000 strong in total, to mount a surprise attack on the outpost town of Trois-Rivières (“Three Rivers” in English), where they expected to overwhelm the 800 British soldiers stationed there.[13] Dressed in ministerial black, Chaplain McCalla marched out of camp with the brown-coated Pennsylvanians, unarmed but ready to help in whatever ways he could.

The American force poled down the St. Lawrence River the night of June 7, landed about nine miles from Trois-Rivières at two in the morning of June 8, and marched down a road along the river toward the town. As the sun rose, they found they had lost the element of surprise. A local guide had deceived them into taking a longer route than necessary, and the HMS Martin and other British ships in the river began spraying the American column with grapeshot. To avoid the incoming fire, the Americans pulled away from the water and found themselves knee-deep in a vegetation-filled swamp. Still, Thompson ordered his force to press on. After four more hours of hiking in the mud the American force emerged in front of the town.

Thompson’s intelligence was horribly wrong. Instead of holding 800 British, Trois-Rivières had been reinforced, and was now defended by several thousand British and Hessian troops, protected by trenches, breastworks, six-pounder cannons, and howitzers. On Thompson’s orders, Wayne’s regiment attacked gamely on the American left, but was quickly outmatched and pushed back. On the right, Irvine and St. Clair also attacked but were forced to withdraw. Wayne mounted a staggered rear-guard defense as the British poured out of their positions and pursued. More British troops began landing behind the Americans from transports on the river, cutting the Americans off from their boats.

The Continentals had no choice but to retreat through the swampland, while the British nipped at them. As they slogged through the water and trees, the American regiments fell apart into companies, and companies broke into smaller groups in the confusion. McCalla stuck close to Colonel Irvine. Irvine later wrote: “Nature perhaps never found a better place calculated for the destruction of an army. It became impossible to preserve any order of march, nay, it became at last so difficult, and the men so fatigued, that their only aim was how to get extricated; many of the men lost their shoes, and some their boots.”[14]

The British commander, Sir Guy Carleton, purposefully allowed the main body of Americans to escape. Carleton told one of his captains: “What would you do with them? Have you spare provisions for them? Or would you send them to Quebec to starve? No, let the poor creatures go home and carry with them a tale which will serve his Majesty more effectually than their capture.”[15] Most of the Americans staggered back to their camp many hours later, pursued by clouds of “monsterous” mosquitoes, while redcoats and Canadian militiamen swept the swamp for stragglers. The Battle of Trois-Rivières was a fiasco that ended with a whimper.

Colonel Irvine and the Reverend McCalla were not among the “poor creatures” who escaped. Irvine, McCalla, General Thompson, and four enlisted men spent the whole day making their way across thickets and marshy ground. “We were fired on from all quarters by the Canadians who were in ambush & skulking among the bushes . . . we waded and wandered here till near daylight [the next day], our strength and spirits being now nearly exhausted.” They stopped and sent out a soldier who found they were surrounded, and saw Canadian troops firing on stragglers. Thompson and Irvine decided it would be “better to deliver ourselves up to British officers, than to run the risk of being murdered in the woods by Canadians . . . we went up to the house where we saw a guard and surrendered ourselves.” The captured American officers were marched back to the British headquarters and were treated well. Irvine wrote that “Generals Carlton and Burgoyne . . . treated us very politely they ordered us victuals and drink immediately, indeed General Burgoyne served us himself.”[16]

A total of 236 Americans were rounded up. Colonel Wayne made it back to the American camp and wrote to Benjamin Franklin a few days later, reporting that Irvine and McCalla were in British hands.[17] Dr. Samuel Kennedy, a surgeon in Wayne’s regiment, referred to McCalla as “our minister” and said of the news, “I am sorry Mr. McCalla and Dr. McKinney [another surgeon] have gone into such imminent danger as it was not their duty nor for the good of the cause.”[18]

* * *

The enlisted prisoners were loaded into the holds of British troop transports. Irvine was quartered aboard the 28-gun frigate HMS Triton, and the British convoy proceeded down the St. Lawence River to Quebec (Quebec City).[19] Irvine remained a prisoner until August 3, 1776, when he was released on parole at Quebec. He signed a parole pledge on his “faith and word of honour” that he would “not do nor say any thing Contrary to the Interest of his Majesty or his government” and that he would “repair to whatever Place his Excellency [General Carleton] or any other of his Majesty’s commander in Chief in America shall judge expedient to order.” [20] Carleton ordered Irvine to return home and to not rejoin his regiment.

The Reverend McCalla, though, was treated abominably. Although chaplains were considered officers (and were paid the same as captains), McCalla was confined below decks on the way to Quebec, and was kept there for two months with enlisted prisoners. The British penalized him because they were displeased by dissenting ministers like Presbyterian preachers, who they viewed as rabble-rousers. Crowded into the hold that summer, the men suffered from poor air circulation, little food, and no medical care. William Hollinshed recounted the “loathsome” conditions the prisoners endured, and the lengths McCalla resorted to during the ordeal: “Mr. McCalla kept a shank bone of a ham for some weeks, which he scraped and shaved with his knife, long after it was stripped of every particle of flesh, and ate the scrapings to give a relish to his spoiled and worm-eaten bread.”[21]

McCalla was released on parole in August, presumably at the same time as Irvine.[22] On August 6, Carleton sent the paroled American officers to New York, in relative comfort.[23]

Irvine and McCalla made their way from New York back to Pennsylvania, and by then they enjoyed a friendship forged in adversity. Irvine returned home to Carlisle and did not rejoin his regiment, as stipulated by his parole. Although the terms of his release required him “not do nor say any thing Contrary to the Interest of his Majesty or his government,” Irvine did not comply strictly. His surviving papers reveal that in October he was administrating financial transactions for the regiment, making sure that his soldiers in Canada were getting paid, and carrying on extensive correspondence with other officers.

McCalla returned to his church outside Philadelphia, eight months after he left. There the “fighting parson” told his flock about the Battle of Trois-Rivières and his shocking imprisonment. Among his congregation was farmer David Todd, whose brother was the Rev. John Todd, a colleague of McCalla’s who resided in northern Virginia.[24] Word of McCalla’s mistreatment likely spread not only to the Reverend Todd, but to all the Presbyterian ministers up and down the mid-Atlantic seaboard.[25]

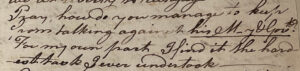

On October 25, McCalla wrote to his friend Irvine, confessing that he was having difficulty keeping the terms of his parole. He asked Irvine, “When shall we be at liberty to reengage? Pray, how do you manage to keep from talking against his M—y & Gov’t? For my own part, I find it the hardest task I ever undertook.”

Months passed, and by the summer of 1777 the British army threatened Philadelphia. McCalla could stand it no longer, and began praying from his pulpit for the colonies, preaching independence again. The British army entered Philadelphia on September 26 and settled in to occupy the city, placing most of its force at Germantown, just north of the city. Washington and the Continental Army attacked Germantown on October 4, with Anthony Wayne (now a brigadier general) leading a division. The assault stalled, and after five bloody hours of fighting the American army withdrew back north, carrying over 500 wounded with it. Ignoring his pledge not to help the Patriot side, and embracing the spirit of mercy, McCalla allowed the army to use his church as a hospital, and Washington visited the wounded there.[26] In December Washington decided to make winter camp at Valley Forge, two miles south of McCalla’s church.

McCalla was in danger. The Continental Army sat as a shield between McCalla’s church and the British, but his activities had attracted the notice of Loyalists, who permeated the countryside around Philadelphia. The British in Philadelphia issued an order to apprehend McCalla for violating his parole. McCalla was exposed to the local Loyalists, and there was always the possibility that the British army could strike toward Valley Forge and the church.

McCalla and his friends received news of the arrest order. It is possible that McCalla was then aided by his congregant David Todd. McCalla resigned his post at the church, and was evacuated far from the action. He soon arrived in Louisa County, Virginia, at the home of David Todd’s brother, the Rev. John Todd.

The Reverend Todd was a true patriot himself, a member of his local Committee of Safety, and a successful military recruiter.[27] Like McCalla, Todd was a graduate of Princeton and a classical scholar and teacher. Todd clearly liked McCalla, and was moved by the sacrifices McCalla had made. After just a few months, the Reverend Todd married his daughter Eliza to McCalla, on April 7, 1778.[28]

That spring, McCalla received news that he was released from parole through an exchange of prisoners. He returned to the “uncontrolled exercise of his ministry,” staying in Virginia with his new family.[29]

William Irvine was soon able to re-enter the fray as well. He was formally exchanged and released from parole on May 6, 1778.[30] Six days later Colonel Irvine was at Valley Forge, where he took an Oath of Allegiance to the United States and resumed command of his regiment. On June 28, 1778 he and his men served at the Battle of Monmouth.[31] Irvine was promoted to brigadier general, and was later named commander of the Western Department at Fort Pitt, where he served until the end of the war.

* * *

When the war ended, both men took advantage of the life and freedom they had earned. William Irvine embarked on a distinguished career in public service. From 1786 to 1788 he represented Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress. He was a member of the Pennsylvania convention for ratifying the Federal Constitution in 1787, and served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1793 to 1795. Although he could be formal and a little awkward in public, he could relax and be himself with his friends, including James Madison.[32] He encouraged fellowship among veterans, was elected president of Pennsylvania’s Society of the Cincinnati and held the office until his death in Philadelphia on July 29, 1804. He was buried near Independence Hall.

David McCalla did what he loved most: he taught, preached, and enjoyed time with his wife Eliza and their daughter. He and his father-in-law John Todd lobbied to make sure that Virginia would disestablish the Anglican Church and be prevented from legislating in religious affairs, an effort that culminated successfully when Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was passed into law in 1786 and became the model for the First Amendment. McCalla “charmed, convinced, and instructed” his congregation.[33] He wrote about politics, under pen names including “A Republican of 76.”[34]

He otherwise lived quietly, which suited him. The Rev. Daniel McCalla died in South Carolina in 1809, at the age of sixty. Late in life he reflected that the war, and the trials he had experienced in it, had all been worth it:

“When ye shall hear of wars, and rumours of wars, be ye not troubled: for, they must be.” –Matthew 24:6.

War is surely one of the greatest calamities that God ever permitted to fall upon mankind, for the punishment of their sins; and no man possessed of the true sensibilities of humanity, can think of it, without horror. But, like every other evil, it is rather to be estimated by the consequences that result from it, than the sufferings that attend it. When the former become more beneficial to society, than the previous state of peace, it is a real good; when they are more injurious, it is a real evil. And this, I think, is the test by which our opinions on the case, are to be determined as just, or the contrary.[35]

[1] Emily Crawford, “Parole: The Past, Present, and Future,” Lieber Institute, West Point Military Academy, lieber.westpoint.edu/lieber-studies-pow-volume-symposium-parole-the-past-present-and-future/. For the rules and disputes over parole terms, see Martin Joseph Clancy, “Rules of Land Warfare During the War of the American Revolution,” World Polity 2 (1960), 510-514.

[2] Holger Hoock, Scars of Independence: America’s Violent Birth (New York: Crown Publishers, 2017), 196-197.

[3] Americans released on parole included generals John Sullivan, Benjamin Lincoln, Daniel Morgan, and Charles Lee. The American traitor Benedict Arnold released British officers on parole so they could transmit information from Arnold back to the British. After the Siege of Yorktown, British general Charles Cornwallis was paroled and free to return to Great Britain, on the condition that he engage in no further military action against the United States; see edu.lva.virginia.gov/oc/stc/entries/general-cornwallis-was-paroled-october-28-1781.

[4] T. Cole Jones, “Washington’s POW Problem,” www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/prisoners-of-war.

[5] Rachel A. Koestler-Grack, Molly Pitcher: Heroine of the War for Independence (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2006), 33.

[6] “B. Gen. William Irvine,” The State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania, pasocietyofthecincinnati.org/gallery_post/b-gen-william-irvine. /

[7] Alan V. Briceland, “Daniel McCalla, 1748-1809: New Side Revolutionary and Jeffersonian,” Journal of Presbyterian History (1962-1985), vol. 56, no. 3 (1978), 252–69. George Howe, History of the Presbyterian Church in South Carolina (Columbia: Duffie & Chapman, 1870), 1:462.

[8] McCalla’s church, the historic Lower Providence Presbyterian Church, thrives today: www.lppcmin.org. Its old building, the Old Norriton Presbyterian Church, was built in 1698 and is the oldest surviving church in Pennsylvania. commons.ptsem.edu/id/norritonpresbyte00coll.

[9] Daniel McCalla,, The Works of the Rev. Daniel M’Calla: to Which Is Prefixed a Funeral Discourse, Containing a Sketch of the Life And Character of the Author, ed. William Hollinshead (Charlestown, SC: John Hoff, 1810), 1:14.

[10] McCalla was appointed to the 1st Pennsylvania Battalion and ended up attached to St. Clair’s regiment. But many of the regiments that went to Canada did not have chaplains of their own, and McCalla aided multiple regiments. Colonial Records of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg: T. Fenn & Company, 1852), 10:458. Some sources erroneously state that McCalla was the only chaplain appointed by Congress. Congress had approved the practice of appointing chaplains; McCalla was then appointed by the provincial council of Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety. This was in keeping with the practice of the time, in which a regiment were raised by a colony, and the colony chose the regiment’s officers.

[11] Charles H. Metzger, “Chaplains in the American Revolution.” The Catholic Historical Review 31, no. 1 (1945): 31–79.

[12] Ibid., 38-39.

[13] Descriptions of the battle are informed by several primary sources. Lt. John Enys of the 29th Foot described the action from HMS Martin’s firing, through the failed assault on the town, to the British mop-up effort. Arthur St. Clair recounted the battle for his biographer William Henry Smith. Colonel Thomas Hartley led the American reserves, and described their march through the swamps and the unsuccessful attack. Wayne’s letter to Franklin included a detailed account of the operation, mentioning particulars such as the British howitzers and breastworks. Additional details from: Charles Henry Jones, History of the Campaign for the Conquest of Canada (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1882), 75-78.

[14] William Irvine, Draft of Irvine’s report of the Battle of Three Rivers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Irvine-Newbold Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 42.

[15] Justin Harvey Smith, Our Struggle For the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907), 416.

[16] Irvine, Draft of Irvine’s report.

[17] Anthony Wayne to Benjamin Franklin, June 13, 1776,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0279.

[18] Samuel Kennedy to Sarah Kennedy, June 29, 1776; in “Notes and Queries,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, VIII (1884), 113ff.

[19] Briceland, “Daniel McCalla,” 258.

[20] Irvine, Draft of Irvine’s report.

[21] McCalla, The Works of the Rev. Daniel M’Calla, 1:15.

[22] Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April,1775, to December, 1783 (Washington, DC: Nichols, Killam & Maffitt, 1893), 272.

[23] George F. Stanley, Canada Invaded, 1775-1776 (Toronto: Hakkert, 1973), 128. Jones, History of the Campaign for the Conquest of Canada, 78.

[24] The Reverends Todd and McCalla met at synods in the years leading up to the Revolution, including in 1775. Records of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1841).

[25] The Presbyterian ministers of colonial America were a tight-knit group, numbering about one hundred from New York through Virginia in 1775. They usually met every year in synod, either in Philadelphia, Princeton, or New York. Records of the Presbyterian Church in the United States.

[26] Charles Collins, Norriton Presbyterian Church, Montgomery County, Penna: regarded as the oldest church in Pennsylvania, claiming connection with the great Protestant Reformation; including historical gleanings pertaining to the early settlers and representatives of the several religious denominations, especially of eastern Pennsylvania (Norristown, PA: Herald Printing Establishment, 1895).

[27] Ms. Wilson G. Todd, “Parson John Todd of Louisa County and His Family,” Louisa County Historical Society, Volume 8, Number 1 (Summer 1976). Piedmont Virginia Digital History: The Land Between the Rivers, www.piedmontvahistory.org/archives14/index.php/items/show/1137.

[28] Ancestry,com: Virginia, U.S., Select Marriages, 1785-1940. Briceland, “Daniel McCalla,” 259.

[29] McCalla, The Works of the Rev. Daniel M’Calla, 1:15.

[30] Heitman, Historical Register of Officers, 238.

[31] One of Irvine’s former servants, Mary Hays, earned fame at Monmouth. There she helped her husband’s artillery unit, becoming a primary inspiration for the legend of Molly Pitcher.

[32] For a touching aside, see William Irvine to James Madison, March 23, 1801,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/02-01-02-0052.

[33] McCalla, The Works of the Rev. Daniel M’Calla, 1:17.

[34] Briceland, “Daniel McCalla,” 264.

[35] McCalla, The Works of the Rev. Daniel M’Calla, 2:305.

4 Comments

A great article. Didn’t Irvine’s son settle in western Pennsylvania, at a village named Irvine. It hosts a museum and a factory which manufactures bunker busting missiles….

Enjoyed this article very much. I’ve read lots of stories about the hard-core Presbyterian ministers in South Carolina and their brothers in Virginia and Pennsylvania were of the same Illick.

Interesting to find out Rev. McCalla’s last years spent not far from where I live in Charleston SC.

Thanks for the posts, Jim and Doug! Glad you enjoyed the article.

Thank you very much for your very informative article, Greg. I found out about General Irvine’s capture as a Colonel when I was researching my first (self published) book, 1780 Battle of the Block House of North Bergen, New Jersey, fought on July 21, 78. Now a Brigadier General, Irvine commanded the 2nd Brigade of the Pennsylvania Line, commanded by Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, at this battle.. I worked diligently with North Bergen Public Library as well as a Township official to get that battle site that includes Fredman’s Park at 75th and Boulevard East on the NJ and National Registers of Historic Places, but we were shot down by Jesse West-Rosenthal, Ph. D. because the ‘integrity’ of the original structure and its bucolic setting had been transformed into an urban setting (Hudson County, NJ is the 6th most densely populated county in our nation.) As a military retiree, I take great offense to his interpretation, because it robs the dignity of respect for the sacrifices made by both sides at this battle, and robs the public of having a tangible marker at this site sanctioned by the gate-keeper of such endeavors. General Wayne personally acknowledged to Governor Reed of Pennsylvania that the larger goal of attacking the British Loyalist block house here was actually successful: delaying the British, who had superior forces on York Island, from engaging the French Forces of Rochambeau which had landed at Rhode Island about 10 days prior. Thanks for all you do to keep the exploits of the Pennsylvania Line in the minds and hearts of our generation and future generations.