Sergeant Solomon Goodwin of Colonel Philip Burr Bradley’s Regiment of Connecticut Levies kept an orderly book for Capt. Bezaleel Beebe’s Company. On November 16, 1776, he added a poignant, personal note: “This Day was the Day that our friends & fellow Soldiers was either killd or taken who were on York Island. This fatal day was a most dismal day to us. In it fell the Flower & Glory of our Regiment, the chief and the best officers and Soldiers that their was in our Regiment.”[1] Nearly half of Beebe’s company had been present at Fort Washington on Manhattan Island when it was attacked and captured by a large British and Hessian force. Sergeant Goodwin watched helplessly from across the river at Fort Lee, noting, “I came from there on the 14th so I escaped with just the skin of my teeth, &c.”

Col. Philip Burr Bradley commanded one of eight regiments of Connecticut State Levies called into service in May 1776 to strengthen the defenses of New York. Capt. Bezaleel Beebe of Litchfield, Connecticut, commanded one of Bradley’s companies raised primarily in Litchfield and Torrington. Captain Beebe was a veteran of the French and Indian War and served previously during the Revolution in the Northern Army as 1st lieutenant in Col. David Wooster’s 1st Connecticut Regiment and in early 1776 as a militia captain with a company of three-month’s men.[2] That year one of Beebe’s soldiers, Robert Little of Litchfield, recalled marching to Norwalk and then taking a sloop to New York, and being there in the city when independence was declared.[3] Bradley’s Regiment soon crossed over to New Jersey and by the second week of August were part of the force protecting the West side of the Hudson River in Bergen County. During September and October they were in the vicinity of Burdett’s Ferry and Fort Constitution, soon to be renamed Fort Lee.[4]

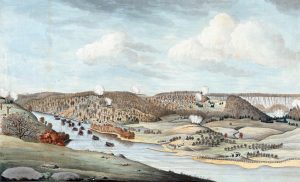

After the Battle of White Plains, Fort Washington at the northern tip of Manhattan became isolated from the rest of Gen. George Washington’s army. Perched high above the river on Harlem Heights, the position was a strong one but not impregnable. Although three British warships had been able to pass upriver despite taking fire from the fortifications on either side of the Hudson, Gen. Nathanael Greene believed Fort Washington was still of strategic importance, writing to General Washington on November 9: “I cannot conceive the Garrison to be in any great danger the men can be brought off at any time—but the stores may not be so easily removed—Yet I think they can be got off in spight of them if matters grow desperate.”[5] His confidence was tragically misplaced, but it was shared by other general officers and so the fort was reinforced instead of evacuated.[6]

Colonel Bradley’s regiment sent large detachments from Fort Lee drawn from each of its eight companies to support the garrison of Fort Washington. Sergeant Goodwin filed a weekly return for Beebe’s Company on November 15, the day before the battle, listing two officers, four sergeants, two drummers and fifty rank and file present and fit for duty out of a total of seventy-six officers and men of all ranks on the company rolls. Two days later he mustered only three sergeants, one drummer and eight rank and file fit and present and a total of forty-one men remaining in the company. Goodwin added a new column under the heading “Alterations since Last Return” listing thirty-five or thirty-six “Killd & Taken Officers Privates.”[7] As the senior noncommissioned officer present he now found himself in charge of what remained of Beebe’s company. Bradley’s regiment overall lost twelve officers and two hundred and fifty-eight enlisted men, and by the end of the month could muster only two staff officers, seven company officers, and one hundred enlisted effectives.[8]

The attack and capture of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776 resulted in the loss of nearly 3,000 defenders, including fifty-nine killed and ninety-six wounded.[9] Three men from Beebe’s company—Cpl. Samuel Cole and Pvts. Joseph Spencer and John Whiting—were missing after the battle and presumed killed.[10] Pvt. John Weed was also thought to have been killed, but he must not have been present with the garrison because he subsequently marched through New Jersey with the remnant of the company and filed a successful pension application on his service that made no mention of being in the battle.[11]

Captain Beebe and thirty-three enlisted men from his company became prisoners of war. Pvt. James Little was one of them, having been wounded in the right side while fighting on the lower lines before retreating into the fort.[12] The prisoners from Fort Washington were first kept in an open field, then marched to Harlem Village and crowded into buildings where they spent the remainder of the night and several more days shivering under guard. Another member of Beebe’s company—Pvt. Oliver Woodruff of Litchfield—remembered that they were held “without anything to eat or drink even the skin of a Potato except the pith of an old cabbage stump which he found in the garden.”[13]

A few days later the prisoners began an arduous march down to captivity in New York. Private Little provided a lengthy, chilling narrative of their suffering as part of his pension application. “being formed into platoons,” he wrote, they “were marched through the British and Hessian Army and were Insulted, kicked, beat with the butt of their Guns, some were knocked down and robd of our Hats and Blankets which was afterwards severely felt as most of us had only summer clothing.”[14] The men staggered from exhaustion but were not permitted to halt or given food or drink and “forced by our extreme thirst,” said Private Little “to sip from our hands the muddy water in the Road.” Upon reaching the city, the captives became objects of great interest to its Loyalist inhabitants:

The Ladies and Gentlemen from the City came to see the Yankey Prisoners, when Sergt [John] Cotton Mather asked a Lady who appeared to be much affected at our situation, if she Could not give him something to Eat She went and soon returnd with and gave him a small Loaf of Bread after thanking the generous Woman he turned and said Comrades you shall share with me and twenty-four of us shared in the Loaf.[15]

“We were separated for Quarters,” remembered Private Little, with the prisoners from Beebe’s company distributed among several places of confinement. Little was sent to a church that had been converted to a prison:

five of my Company with a great Number of others were put in the North Chapel . . . We drew three days Allowance my share which was of Bran Bread was about a double handfull mouldy and full of Worms with two ounces of Pork . . . I ate the whole and then went three days more without food so that in eight days I had one meal.[16]

The other five men with him were Zebulon Bissell, Aaron Stoddard, John Parmelee, Joel Taylor and Phineas Goodwin. None of the five made it home to Litchfield.[17]

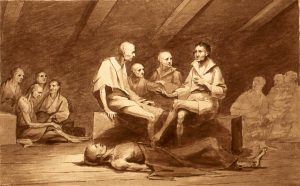

Private Woodruff “with eight hundred and fifteen others was imprisoned in New Bridewell then unfinished with loose floors and no windows—first food after captivity [the previous Saturday] was on Thursday morning.”[18] Private Woodruff remained in the Bridewell jail until sometime in January, 1777 “without fire suffering more than has ever been written or told.” Pvt. Remembrance Loomis was the only other man there from Beebe’s company.

There were by now over five thousand American soldiers held captive in New York, including those taken during the Battle of Long Island and the chaotic retreat of General Washington’s army from the city in mid-September. Not only the provost and Bridewell jails but also city Hall, two sugar warehouses, churches and the troop transports Whitby and Grosvenor now served as prisons. Even had they been inclined to provide adequate food, clothing and shelter to so many men who had been taken in arms while in open rebellion, the enormity of the logistical challenge far exceeded the capacity of the occupying British authorities. Instead, a fatal mix of neglect, incompetence and abuse led to the deaths of hundreds during that winter.[19]

Captain Bebee was able to move about within the confines of the city while on parole. He spent the next few months diligently trying to determine what had become of the men from his company. His record—“An Account of the Prisoners Names and Places of Confinement”—is a grim litany of death with few survivors.[20] Twenty-eight of his men died in prison or of diseases contracted there, including from an epidemic of smallpox. Pvt. Isaac Grant of Judea in Litchfield, a prisoner from Capt. Benjamin Mills’ company of Bradley’s regiment, remarked that after first being held in a church and then being transferred to the prison hulk Grosvenor, he “had the smallpox in the natural way.”[21] Connecticut still prosecuted people for getting inoculated without state sanction, and it is doubtful that anyone in Bradley’s regiment had been exposed to smallpox before now.

Most of the prisoners from Beebe’s company were confined in one of the notorious Sugar Houses: massive six-story stone buildings. Pvt. Enos Austin died there of smallpox on December 4 and there were many more deaths to follow.[22] Private Little alleged that several of the healthiest prisoners held with him in the New Chapel were forcibly impressed into British service. Later in December he and many of the sickest men were moved into the prison ship Grosvenor where nearly all of them suffered from smallpox. Among those who died on the Grosvenor were Cpl. David Hall and Pvts. Gershom Gibbs, Isaac Gibbs, Alexander McNeil, Timothy Stanley, Samuel Vaill and Solomon Parmelee; of the latter, Captain Beebe wrote that he “went on board the ship, and I fear he is drowned as I cannot find him.”[23]

By this time, both Pvts. Oliver Woodruff and Isaac Grant were also on the Grosvenor. Woodruff misremembered the name of the prison ship as the Glasgow, a different vessel that was later used for a cartel,[24] but he was very clear that the hulk “moved from New York Harbor in Hell Gate where she cast anchor where she lay for 10 or 12 days during which time 28 of the Prisoners died from disease occasioned by hard treatment and hunger.”[25] Private Little described the ship as “a two decker and so crowded that there was not room for us to lie down.”[26] The Grosvenor was not a hospital ship but a place to quarantine sickened and contagious men. Those from Beebe’s company and their fellows on board struggled to survive on “about three pints of Burgoo or Water Gruel without Salt in a Bowl for six men in the morning and at night about a handful of Kennel Biscuit . . . but when the Small Pox began to rage our case seemed deplorable, Indeed death and distress was on every side.”[27]

James Little recounted bitterly how the bodies of the dead “were hoisted on deck a Cannonball fastened to them and then thrown overboard with a shout of there goes Another Damd Yanke Rebel.”[28] Although the men were given the option of going ashore to bury their dead, he could recall only one instance when this was done, with disastrous consequences. Solomon Gibbs of Beebe’s company died on the ship on December 29, 1776. His teenaged son Isaac convinced one of their fellow townsmen from Litchfield, Alexander McNeil, to help him bury his father. “to go abroad from the Confined air in the hold of the Vessel provd almost Instant Death,” Little observed grimly. His messmates Gibbs and McNeil “got so chilled & frozen that they died soon after their return . . . My last messmate young Gibbs before he died [on Jan 15, 1777] was frozen from his feet to his hips.”[29]

Little and Woodruff endured unimaginable horrors while aboard the Grosvenor, their “situation hopeless and pitiless faint and feeble confined in the putrefied stagnated air of the hold of the Vessel & covered with Vermin.”[30] Finally, after about six weeks, those who had smallpox were visited by a doctor and according to Little about forty were removed to a house on shore where nearly all of them were dead within a fortnight. His fellow townsmen Isaac Grant from Bradley’s Regiment and Elihu Grant, who had been detached from the 19th Continental Regiment to serve in Knowlton’s Rangers, survived in the house with him.[31] Isaac Grant described how after most of his companions died, he was visited by Levi Allen, the Loyalist brother of Ethan Allen, who interceded “with the Commissary of the Prisoners and got him out of the hospital and he was billeted out in the city and clothed by him.”[32] Little also recalled that Allen, formerly a resident of Salisbury, Connecticut, brought them clothing. At this time Oliver Woodruff remained on board the Grosvenor and Sergeant Mather somehow was still alive in the Sugarhouse. There were not many more of them left.

On February 20, 1777, a cartel ship deposited about two hundred sick and starving men at Milford Neck on Long Island Sound, and around the same time at Rye, New York “the Commanding Officer gave a receipt for nineteen almost dead men.”[33] Among these paroled survivors were eleven from Beebe’s company who were left to shift for themselves and make their way home as best they could. Many died on the road, among whom were Barnius Beach, Zebulon Bissell who got as far as Woodbury, Elisha Brownson, Remembrance Loomis, Timothy Marsh and Oliver Marshall. Thomas Mason died shortly after he arrived home in Litchfield.[34]

A few survived. James Little, who started walking at Rye, was so weakened that he stopped in Danbury and was taken in by a friend until his father arrived from Litchfield to care for him. Oliver Woodruff and Noah Beach made it back to Litchfield. Both Elihu and Isaac Grant also arrived home at Judea together, and by some miracle Sergeant Mather survived the Sugarhouse and made his way back to Sharon, Connecticut. Daniel Benedict also made it back to Litchfield County, but that was all. Oliver Woodruff was correct, however, when he recounted in his pension that “out of the thirty three of Captain Beebe’s company that were made prisoner, only two beside himself ever arrived at home” in Litchfield.[35] Including the three men lost at Fort Washington, the detachment from Beebe’s company suffered an 86 percent death rate. If the same held true for their fellows from the other seven companies of Bradley’s Regiment who were at Fort Washington, there may have been as few as thirty-six enlisted men who survived their ordeal and quite possibly even fewer. Capt. Noble Benedict reportedly lost all but two of twenty-eight enlisted men who served with him at Fort Washington.[36]

Remarkably, Isaac Grant, James Little and Oliver Woodruff recovered their health and soon returned to service. Little remained in the militia and responded to the Danbury Alarm in April 1777. Grant joined his old commander Colonel Bradley in the new 5th Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Line. Woodruff shipped on a privateer out of New London in 1778 during which “nothing occurred of importance” and returned to port after a cruise of thirty days. Sgt. Solomon Goodwin dusted off his old orderly book in 1780 and accepted a warrant as sergeant major under Bezaleel Beebe, now colonel of a regiment of state troops guarding Horse Neck on Long Island Sound.[37]

Late in life while living in Vermont, James Little tried to qualify for a pension and was frustrated by a bureaucracy that failed to credit him for sufficient time in service. His application was “rejected by the Secretary for the war department on account of my enlistment being only for eight months,” he declared,

Notwithstanding I was taken prisoner and kept over the time that is considered sufficient to come within the Law to be entitled to a Pension. I would take the liberty to forward my declaration that the whole subject may be before you and in addition to what is there stated may I be permitted to mention some of the cruel treatment I underwent while a Prisoner.[38]

Both Little’s and Woodruff’s harrowing records of neglect and inhumanity while in prison are a poignant reminder that thousands of revolutionary captives died in New York from what one historian calls “a lethal convergence . . . of obstinacy, condescension, corruption, mendacity, and indifference.”[39] There are many contemporary accounts like these, too many to ignore.

The impact of all those losses on their home communities defies the imagination. Both John Parmelee and his uncle Solomon were gone, as was Gershom Gibbs who entered the fort a few days before the battle as a substitute for one son and then died in captivity along with another. The father of Pvt. Noah Barnum, one of the men in Captain Benedict’s company of Bradley’s Levies, learned that his son died of hunger in prison after having attempted to eat a piece of brick. Wild with grief and anger, he reportedly went out the following day and shot and wounded a Loyalist neighbor who was working on his own land.[40] This war, like all wars, was filled with trauma and marked by inhumanity as well as courage.

[1] Orderly Book, 1776 Jul 19—Nov 17, 1780, Litchfield Historical Society (LHS), Beebe Family Papers, Box 1, Series 2, Folder 2.6.

[2] 1st Lieutenant’s Commission, Litchfield Historical Society (LHS), Beebe Family Papers, Box 1, Series 2, Folder 2.2.; Alain Campbell White, ed., The History of the Town of Litchfield 1720 -1920 (Litchfield, CT: Enquirer Print, 1920), 74.

[3] James Little Pension (W.8256), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), (RG93) M804, Revolutionary War Pensions.

[4] Bradley’s Regiment, NARA, (RG93) M246, Revolutionary War Rolls, Folder 195, Roll 27.

[5] Nathaniel Greene to George Washington, November 9, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0085.

[6] Derrick E. Lapp, “The Fall of Fort Washington: The Bunker Hill Effect”?, Journal of the American Revolution, July 7, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/07/the-fall-of-fort-washington-the-bunker-hill-effect/.

[7] Orderly Book, 1776 Jul 19—Nov 17, 1780.

[8] Bradley’s Regiment, NARA.

[9] Lapp, “The Fall of Fort Washington.”

[10] White, The History of the Town of Litchfield, 77.

[11] John Weed Pension (S.23999), NARA.

[12] James Little Pension (W.8256), NARA.

[13] Oliver Woodruff Pension (S.14885), NARA.

[14] James Little Pension (W.8256), NARA.

[15] Ibid.

[16] James Little Pension (W.8256), NARA.

[17] White, The History of the Town of Litchfield, 76, 77.

[18] Oliver Woodruff Pension (S.14885).

[19] Edwin G. Burrows, Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners During the Revolutionary War (New York: basic Books, 2008), 45-52.

[20] White, The History of the Town of Litchfield, 76, 77.

[21] Isaac Grant Pension (R.4195), NARA.

[22] White, The History of the Town of Litchfield, 76,77.

[23] Ibid., 77.

[24] Burrows, Forgotten Patriots, 63.

[25] Oliver Woodruff Pension (S.14885), NARA.

[26] James Little Pension (W.8256), NARA.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Elihu Grant Pension (R.4194), NARA.

[32] Isaac Grant Pension (R.4195); James Little Pension (W.8256), NARA.

[33] Oliver Woodruff Pension (S.14885), NARA.

[34] White, The History of the Town of Litchfield, 77.

[35] Oliver Woodruff Pension (S.14885), NARA.

[36] Royal R. Hinman, A Historical Collection From Offical Records, Files, &c., of the Part Sustained by Connecticut During the War of the Revolution (Hartford, CT: E. Gleason, 1842), 137. Hinman claims Benedict had fifty men in his detachment, but a subsequent return records twenty-eight enlisted men taken with Benedict on November 16, 1776. Bradley’s Regiment, NARA, (RG93).

[37] James Little Pension (W.8256); Isaac Grant Pension (R.4195); Oliver Woodruff Pension (S.14885); Solomon Goodwin Pension (W.24,283), NARA (RG93) M804, Revolutionary War Pensions; Orderly Book, 1776 Jul 19—Nov 17, 1780, Litchfield Historical Society (LHS), Beebe Family Papers, Box 1, Series 2, Folder 2.6.

[38] James Little Pension (W.8256) NARA.

[39] Burrows, Forgotten Patriots, xi.

[40] Hinman, A Historical Collection, 137.

3 Comments

Thanks for a well-organized and well-written article about Beebe’s men after the fall of Fort Washington. My knowledge of his activities is based later, in Horseneck. I’d had no idea of the fate of his earlier company. I appreciate your good work.

Thanks, Selden. It’s one of those stories that needed telling. I first encountered it when helping Litchfield plan for its 300th anniversary. The fact that Captain Beebe tried to determine what had happened to his men while he was a prisoner on parole speaks to his character. Solomon Goodwin writing what he did in the orderly book is also telling. Private Little’s pension account of their suffering is among the most extraordinary and haunting of the many hundreds of declarations I have read over the years. This time around I wanted to know if what happened in Beebe’s company was comparable to the others in Bradley’s State Levies and there is every indication of the same awful arithmetic in those as well.

Thank you for documenting the ordeal so many prisoners from Connecticut encountered during the Revolution.