Most stories have a chief villain. The story of the American Revolution is no different. One man stands out amongst all the rest in the minds of Massachusetts revolutionary leaders. James Otis, Samuel Adams, and especially John Adams accused Thomas Hutchinson as being the architect of all the oppressive laws that were being passed by the British parliament with respect to the American colonies.

Thomas Hutchinson was no English lord, sent from Britain to govern an American colony. He was born and raised in Massachusetts, graduated from Harvard College and lived in Massachusetts his whole life. His family could trace its roots back to the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay colony in the 1630s.

One of his ancestors, Anne Hutchinson came to Massachusetts from England with her husband. She was an outspoken woman who told people that Puritan ministers did not have the only say in interpreting the gospels, that the Holy Spirit could guide each individual. Massachusetts, at that time, was a theocracy. The authorities banished her from Massachusetts, not to return, upon pain of death. It caused Thomas Hutchinson to “despise the fanaticism of the Puritans . . . laced as it was with those fine-spun doctrinal subtleties that led men to torture each other in passionate self-righteousness.”[1]

The rest of the Hutchinson clan remained in Massachusetts and with each generation they became increasingly wealthy as merchants. The head of the families became influential in the colony, filing positions of judgeships and militia officers. Thomas Hutchinson decided that he did not want that kind of life and chose instead to go into public service, in other words, politics. When he told his father this, he replied, “Depend upon it, if you serve your country faithfully you will be reproached and reviled for doing it.”[2] Little did he know just how true this statement was to become.

Hutchinson was elected to the House of Representatives for the colony at age twenty-six and served faithfully, from 1737 to 1749. For the next seventeen years he served on the governor’s council.[3] He represented Massachusetts in boundary disputes with other colonies, participated in negotiations with Native Americans, and was one of Massachusetts’ representatives to the Albany Conference during the French and Indian War. He signed and approved the plan of union that Benjamin Franklin drew up. He also became the probate judge for the surrounding county. He was a very popular judge and his reputation for honesty and fairness was well known.

He was eventually chosen to be the lieutenant governor for the colony. When a new governor arrived from Britain to take over the governorship, something happened that would change Hutchinson’s life forever. The previous governor had promised James Otis, Sr. the next open position on the Supreme Court. Shortly after the new governor appeared, the chief justice of the Supreme Court died. The new governor chose Thomas Hutchinson for the position. Under the laws at that time, Hutchinson could keep all three jobs at the same time—probate judge, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and the lieutenant governorship. He advised that the position had already been promised to Otis, a well-respected member of the legislature. In fact, a few days earlier, James Otis, Jr. had asked Hutchinson to help his father get the judgeship. The governor told Hutchinson that Otis was not going to get the job, as he was felt too tied to the popular party and not supportive enough of British rule; if Hutchinson did not want the job, he would find a third candidate, because in no way was Otis going to get the judgeship. Hutchinson, after thinking on it, accepted the appointment, but told the governor that this might be a political mistake. Accepting this position put him forever at odds with the popular party, led at that time by James Otis, Jr.

Hutchinson took his job as Chief Justice seriously. Even his opponents reported that his judgements “had generally been fair, his appointments sensible, and his attachment to the colony, well publicized”.[4] He was amiable and friendly with the common people with whom he would work and talk to as he walked the streets. At one point later in his career Hutchinson was thinking of retiring from his position as lieutenant governor. He wrote that he “wondered if he would ever be effective in the administration of the colony. He had been Chief Justice for about ten years,” in which he said that the position “offered him more satisfaction than he had ever received in the legislature or administration.”[5]

At that time, all search warrants issued in the British Empire had to be authorized in the name of the King. When George II died and George III and assumed the throne, all old warrants were invalid and new warrants had to be issued in the name of the new king. One of those warrants was called the Writs of Assistance. A customs officer would ask a court to appoint someone, usually the local sheriff, to assist him in searching a particular warehouse, building or ship that had just arrived. A number of merchants decided to sue the Massachusetts government to prevent issuance of the new writs. After the trial, chief judge Thomas Hutchinson wrote to London saying that he and the other judges had “considered the subject of the writs and can find no foundation for such a writ.”[6]

From this point on the line between British authority and American rights became increasingly contentious. In many ways Hutchinson agreed with those who opposed parliament; while he could privately advise his superiors of his views, as a crown official he had to keep silent publicly and enforce the laws on the books.

On March 5, 1770 things almost exploded. It was Hutchinson who kept things under control. On that night a lone British soldier guarding the customs house in Boston was surrounded and taunted by a crowd throwing snowballs and chunks. He called for assistance; an officer with a squad of soldiers went to the scene. The crowd got uglier and before it was over the soldiers shot and killed five civilians and wounded six others. The crowd then dispersed and the soldiers retreated to their barracks. Upon hearing of the event Hutchinson went to the guard house and questioned the officer. He then went to the Council chambers and addressed a large crowd that had gathered. He told the people that he would begin an investigation and promised that “the law shall have its course; I will live and die by the law.” His reputation as a judge still carried weight and the crowd dispersed. He immediately ordered the justices of the peace to take depositions from eye witnesses.[7]

The soldiers and the officer were tried for murder. All but two of the soldiers were acquitted. Two were found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to be branded on the thumb; should they ever be charged of a crime again, they would face the death penalty. There was an application to Hutchinson to pardon the two convicted men so that they would not have to be branded, but “it was thought most advisable not to interpose” because this would incite the population more, as the radicals were already disappointed enough that the other men had been found not guilty.”[8]

After the trial, Samuel Adams did his best to make the issue play large in the resistance movement. He organized speeches every March 5 from 1771 to 1789 as memorials to the “massacred victims” and made sure that everyone knew that it was all Thomas Hutchinson’s fault.[9] John Adams wrote of the polemics that Samuel Adams was printing, “was propaganda to stop at nothing, even the complete destruction of the truth?”[10] In addition, Samuel Adams was continually writing inflammatory stories in the newspapers about the event and constantly accusing Hutchinson of being behind the murders. Hutchinson had had enough and he wrote to the secretary of state offering to resign. The secretary replied that “no one had ever given more satisfaction than he. If he would accept the governorship, he would never regret it.” Hutchinson accepted the promotion.[11]

In spite of Samuel Adams’ best efforts, things actually settled down and were fairly peaceable for a couple of years.

In 1774 Hutchinson began to hear stories and read in the papers things about him that came from a particular source in Britain. He had written a series of letters to people in London trying to explain the political tensions in the colony and how he was trying to control the situation. He also made a number of recommendations about how to deal with the issues. The letters were “restrained and candid. They contained no sentiments he had not previously proclaimed”. But when they were published in 1773, “they sent a thunderous wave reverberating across the Atlantic Ocean.”[12] The radicals, in publishing the letters, “latched on the very few lines that sounded most tyrannical.”[13]

Hutchinson’s letters had fallen into the hands of Benjamin Franklin, who had been living in Britain for fifteen years at this time. He never revealed from whom he got the letters; that he had them was illegal and he knew it, but the stakes were too high not to show them to someone. As Franklin saw it, the letters not only implicated Hutchinson as the cause of the rift between America and Britain, they also cleared British officials. If the radicals in Boston could see the letters, they would stop blaming officials in London and turn their fire directly onto Hutchinson. Conversely, if officials in London knew of Hutchinson’s guilt, they would dismiss him and reconciliation would be possible.[14]

Franklin decided to send the letters to Thomas Cushing, the Speaker of the Massachusetts Assembly, which was firmly in the control of the radicals. In his cover letter Franklin stated that the letters should not be printed, no copies made, “and that they were to be returned to him.”[15]

When the legislature in Boston received the letters, they followed none of Franklin’s instructions. At first the speaker only circulated them among a few people. But rumors began to spread. Then Samuel Adams read them aloud to the entire assembly. To get around Franklin’s instructions, Adams told a little fib—he told the assembly that he had come across copies of the letters separate from those Franklin sent (no such copies have ever been found).[16] The House immediately voted that the letters be published, declaring that they “show a tendency and design . . . to overthrow the constitution of the government and introduce arbitrary power.”[17]

The letters showed no such thing, but that mattered little to the radicals. The letters were released to the public after they “had been carefully edited to maximize the desired effect.”[18] Adams had “edited the letters so subtly that it was impossible to tell whether it was the writer of the letters, or Adams that was speaking.”[19]

The assembly also declared that Thomas Hutchinson’s letters “had a natural tendency to interrupt . . . the affections of our most gracious sovereign, King George III, from his loyal and affectionate province . . . and to prevent repeated petitions from reaching the Royal ears of our sovereign, and to produce severe and destructive measures which have been taken up against this province.” They further asked that the king “remove forever from the government of Massachusetts, his excellency Thomas Hutchinson.”[20] They attached the original letters Franklin had sent them to the petition and sent them to Franklin to submit to the king. One would think that when Franklin received this packet, which clearly did not accord with his instructions, he would have suspected this would not go down well. But he did as he was told and submitted them along with a cover letter of his own, assuring the king that the colony had a “sincere desire” to be on good terms with the “mother country,” and as having discovered that the cause of the distractions was one “of their own people, their resentment against Britain is now much abated”.[21]

Arthur Lee, the youngest brother of Virginia’s leading plantation family, was studying in England at the time and had become a regular correspondent with Samuel Adams. He wrote to Adams that the letters raised the Anglo-American controversy “to a level of explosive enmity.”[22] This reaction was exactly the opposite of what Franklin had expected. Meanwhile, in Boston, up to this time Hutchinson had been widely respected and well regarded by many people. The publication of the letters changed everything.[23]

Hutchinson was stunned over the production of the letters and the reaction they produced. He knew what was published was not put into the same context that he had written, but throughout America he was being accused for views that he never expressed.[24] He saw his reputation being tarnished beyond repair. Jonathan Sewall, a friend of Hutchinson, had a letter defending Hutchinson published in which he asked, “whose ox had he taken? Whom had he defrauded? Whom had he oppressed? From whose hands had he accepted a bribe?”[25]

By now Hutchinson had had enough. He wrote to the secretary of state requesting to be allowed to resign or be given and immediate acquittal of the charges against him. He was tired of standing alone. It was time for crown officials to back him up or cut him loose.

The reaction in Massachusetts was pretty much what Franklin had hoped for. Their anger was now focused solely on Hutchinson. But in England the reaction was exactly the opposite. In Britain, rather than seeing Hutchinson as the culprit, they him as the victim. British officials and the public at large were outraged at the publication of the letters. There was an instant search for the person who had stolen the letters and sent them to America. As they were about to charge the wrong man, Franklin wrote to the secretary of state and admitted that it was he who had sent the letters to America, but he refused to say who had given them to him.[26]

Franklin was ordered to appear before the King’s Privy Council. The subject was going to be the letters and his role in their publication. Present in the council room was Lord North, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Shelbourne, Edmund Burke, and thirty-five members of the privy council. People could not remember the last time so many privy council members had attended.[27]

But this was not going to be a hearing, it was going to be a trial.[28] Franklin’s attorneys admitted that the Massachusetts assembly had no intention of bringing any charges against Hutchinson. That of itself, was an amazing admission. They admitted that the complaint of the Massachusetts legislature against Hutchinson was solely that he “was obnoxious to the people of the province.”[29]

The Attorney General for the crown, Alexander Wedderburn, rose to speak next. As Wedderburn spoke it became clear just how angry the people of Britain were over the publication of the letters and the petition from Massachusetts. Every time parliament would pass a new tax bill, the colonists would object, and parliament would rescind or modify the act in an effort to please the colonists, only to have the Americans still claim they were being made slaves.

Wedderburn began by reading aloud the letters that Hutchinson wrote to everyone in the room. He was able disprove accusations against Hutchinson, and described Hutchinson as a “benevolent man of service, a keeper of the peace and not a villain.” The radicals, he said, “mean nothing more by this than . . . to fix a stigma on the governor by accusation . . . there is no cause to try—there is no charge—there are no proofs.” And it was Benjamin Franklin who had concocted the whole affair, it was Franklin who was “the great abettor of that faction in Boston; that it was Franklin that was the true incendiary.” The letters did not come to Franklin by fair means. “I hope, my lords, you will mark the man . . . [People] will hide their papers from him, and lock their writing desks.”[30] Wedderburn concluded by saying, “nothing then will acquit Dr. Franklin of the charge of obtaining [the letters] by fraudulent means, for the most meager of purposes.” At that point the galleries erupted in applause.[31]

Arthur Lee was sitting in the balcony watching the proceedings and was stunned by the degree to which Wedderburn praised Hutchinson and condemned the Americans, especially Franklin. He then wrote to Samuel Adams, saying that the people of Boston “ought to prepare for the worst,” that the request for Hutchinson’s dismissal was, in the eyes of the British, “groundless, vexatious, and scandalous . . . It is impossible for me to describe the rancor and sanguinary sentiments which prevail here, I vow to God, I believe they would make no ceremony of taking some of our lives.”[32]

By now King George III had had enough. He wrote to Lord North that it appeared that “vigorous measures appeared to be the only means left to bring the Americans to a due submission to the mother country . . . the colonies will submit!”[33]

Back in Boston, while the British were still fuming over the affair of the letters, the radicals were about to make things worse.

The British had again backtracked on all tax proposals except the tax on the tea imported to America, but Americans had concluded that they would pay no tax. When three ships carrying tea arrived in Boston, the populace demanded that the tea not be unloaded and the ships sent back directly to England. The problem was that the tea belonged to the East India Tea Company, and no one in America had the legal authority to order it back. The people to whom it was shipped were simply agents for the East India Company who were to sell the tea to merchants. The agents could not send it back. As no one could legally send it back, the customs office had no authority to give it clearance to leave the port. The customs officer went to Hutchinson, the acting governor, to seek a clearance. Hutchinson replied that “no pass had ever been, or lawfully could be, given to any vessel which had not first been cleared at the customs house, and that, upon the customs officer producing a clearance, such a pass would immediately be given by the naval officer.”[34]

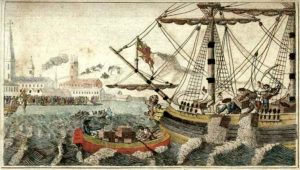

The people who were to receive the tea and the ship captains offered to store the tea in a warehouse and not sell it until further instructions came from England. They offered to let the populace place guards to make sure the tea was not moved until then, but the radicals refused this compromise. While the negotiations back and forth were going on, the radicals gathered “about fifty men at the wharf . . . covered with blankets, and making the appearance of Indians.” After hearing of the governor’s refusal to issue a pass, they “hoisted out of the holds of the ships, three hundred forty- two chests of tea and emptied them into the sea.”[35]

Hutchinson later explained his decision that day. He said that “granting a pass to a vessel which had not cleared at the customs house, would have been a direct violation of his oath, by making himself an accessory in the breach of those laws which he had sworn to observe.”[36] He further pointed out that with the hostile intent of the populace the only way the tea could have been landed and stored was to land “marines from the men of war, or bring to the town [an army regiment] to remove the guards from the ships and to take their places. This,” he wrote, “would have brought on a greater convulsion than there was in 1770 . . . Such a measure, [he] had no reason to suppose would have been approved of in England.”[37] Hutchinson felt that he could not depend on the support of any one person in authority. The house of representatives,

openly avowed the principles which implied complete independency. The council, appointed by charter to be assisting the governor, declared against any advice from which might be inferred an acknowledgement of the authority of parliament in imposing taxes. The superior judges were intimidated from acting upon their own judgement . . . there was not a justice of the peace, sheriff, constable, or peace officer in the province, who would venture to take cognizance of any breach of the law, against the general bent of the people.

The military authority [provincial militia], which by charter was given to the governor, had been assumed by the body of the people . . . Even the declarations of the governor against the unlawful invasions of the people upon the authority of the government, were charged against him as officious and unnecessary acts, and were made to inflame the people and incite disorders . . . He could not take any measures for his security, without the charge of needless precaution, in order to bring an odium against the people, when they meant him no harm[38]

Hutchinson admitted that the destruction of the tea “was the boldest stroke which had yet been struck in America . . . the thing being done: there was no way of nullifying it. The leaders feared no consequences . . . They had gone too far to recede”.[39]

When word of the tea’s destruction reached London, where tensions were already high over the letters, the king and Parliament drew a line in the sand. Britain was retreating no further. The first thing the king did was to close the port of Boston. The bill passed both houses of parliament unanimously and the king signed it immediately.[40] They also accepted Hutchinson’s request to be relieved. In his stead, Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, commander in chief of the British army in America, took over. Also, the charter for Massachusetts was revoked, and the legislature no longer had the authority to elect the governor’s council; they would be appointed by Gage. Up until this time, the House had packed the council with radicals so that both houses of the legislature were under their control, leaving Hutchinson totally alone in dealing with one crisis after another. Under the law, the governor could not call upon the army to quell riots without the concurrence of the council and they were not going to give him that authority.

When the people heard about the British reaction to their petition to get rid of Hutchinson, it was their turn to be stunned. This is not what they were expecting, though one has to wonder how they could, in reality, expect anything else.

On June 1, 1774 Thomas Hutchinson, the last civilian Royal Governor of Massachusetts, boarded a ship in Boston and set sail for Great Britain. As he did, he reflected on the turmoil he was leaving behind:

The course of the law was now wholly stopped . . . all legislative as well as executive power were gone, and the danger of revolt was daily increasing. The new governor had the title of Captain-General, but he had the title only. The inhabitants, in many parts of the province were learning to use of firearms, but not under officers of the [militia] regiment to which they belonged . . . The people had been persuaded that their religion, as well as their liberty, was in danger. It was immaterial whether they had been deceived or not—the persuasion was the same . . . the apprehension of punishment, now ceased. Impunity for so many past breaches of the law, and the great number of persons now involved, caused them to depend on like impunity for every future breach.[41]

As he left, he

received the several addresses of one hundred twenty of the merchants and principle gentlemen of the town of Boston . . . Middlesex . . . Salem . . . Plymouth and Marblehead expressing their approbation of his public conduct . . . many of the addressees who were without protection, and were afterwords compelled by the people to make their recantation, and to publish them in the newspapers.[42]

Before leaving Hutchinson was told by Gage that he was held in the “highest esteem” by authorities in London. Hutchinson wrote to a friend that “I may return to my government whenever it is agreeable”.[43]

Hutchinson had no plans to leave Massachusetts permanently, but events developed that kept him away from his home and ancestral lands for the rest of his life, just as his ancestor Anne Hutchinson had in the earliest days of the settlement of the colony.[44]

As soon as he landed in Britain, he was immediately called to London, without even changing his clothes. He was immediately taken to the king, who received him warmly. Hutchinson apologized for his clothing and appearance.[45] The king asked him about the nature of the resistance in New England and the situation with the Native Americans. Hutchinson replied that much of the Native Americans’ condition was due to “their low and despicable” treatment by Europeans, who “have taken their land, and treated them as an inferior race of beings.”[46]

Hutchinson was informed that the king was willing to make him a baron, a noble who would sit in the House of Lords. Also, the possibility of a governorship somewhere else in the Empire was offered to him. Hutchinson turned down all of the offers, saying, “I hope to leave my bones where I found them and that before I part with them, I shall convince my countrymen I have ever sincerely aimed at their true interest.”[47] He did accept a pension of £2,000 a year as he had no other way to support himself. He said, “I am like an old Athenian, I can’t bear the thought of laying my bones anywhere but with my ancestors and friends . . . in my native land.”[48]

For a while he tried his best to seek a compromise between America and Britain. He was frequently asked by government officials for his advice on matters concerning America, but after independence was declared he was largely irrelevant. He was still invited by the king and other noblemen to spend days with them and attend their parties, but he longed for home. In February 1776 he told people to stop addressing him as “His Excellency,” his title as governor. He said there was nothing so “like and old almoner as an old governor.”[49] After independence was declared, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law forbidding Hutchinson to ever return. His house that he loved so dearly was confiscated and sold.

He busied his time completing his History of Massachusetts. In the last paragraph he wrote, “the people, by their own authority, formed a legislative body; and from that time all pacific measures upon the supreme authority of the British Dominions were of no purpose.”[50] After completing the book, he ordered that it not be published until after his death.[51]

On June 3, 1780 Thomas Hutchinson died of a stroke in England, and his remains have never been allowed to return home.

[1] Bernard Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1974), 20.

[2] Ibid., 253.

[3] Ibid., 13.

[4] Ibid., 245.

[5] Thomas Hutchinson, The History of Massachusetts Bay, 1749-1774 (London: John Murray, 1828), 290.

[6] William Tudor, The Life of James Otis of Massachusetts (Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1823), 86.

[7] J. Langguth, Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 149.

[8] Hutchinson, The History of Massachusetts, 329.

[9] Hiller B. Zobel, The Boston Massacre (New York: W. Norton & Co., 1970), 135.

[10] Catherine Drinker Bowen, John Adams and the American Revolution (Boston: An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Little, Brown & Co., 1950), 410.

[11] Langguth, Patriots, 162

[12] Louis W. Potts, Arthur Lee: A Virtuous Revolutionary (Baton Rouge: Louisianna State University Press, 1981), 106.

[13] Derek W. Beck, Igniting the American Revolution, 1773-1775 (Naperville, Il, Sourcebooks, 2015), 20.

[14] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 236.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Langguth, Patriots, 172.

[17] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 238-241.

[18] John Ferling, John Adams: A Life (New York: Holt and Company, 1992), 81.

[19] Richard M. Ketchum, Divided Loyalties: How the American Revolution Came to New York (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2002), 252.

[20] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 240-241.

[21] Ibid., 241-242.

[22] Potts, Arthus Lee, 106.

[23] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 243.

[24] Langguth, Patriots, 173.

[25] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 247.

[26] Ibid., 254-255.

[27] H.W. Brands, The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Doubleday, 2000), 470.

[28] Beck, Igniting the American Revolution, 15-19.

[29] Hutchinson, The History of Massachusetts Bay, 417ff.

[30] Ketchum, Divided Loyalties, 254.

[31] Langguth, Patriots, 186.

[32] Potts, Arthur Lee, 120-121.

[33] Beck, Igniting the American Revolution, 21-29.

[34] Hutchinson, The History of Massachusetts Bay, 435.

[35] Ibid., 436-437.

[36] Ibid., 437.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid., 437-438.

[39] Ibid., 488-489.

[40] Beck, Igniting the American Revolution, 30.

[41] Hutchinson, History of Massachusetts Bay, 455.

[42] Ibid, 459.

[43] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 290ff.

[44] Ibid., 291.

[45] Langguth, Patriots, 192-193.

[46] Ibid., 194-196.

[47] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 292.

[48] Ibid., 328.

[49] Ibid., 345.

[50] Hutchinson, History of Massachusetts Bay, 460.

[51] Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson, 384-385.

2 Comments

Thoroughly enjoyed this. Thanks for writing it.

This is rather sad…that he could not be returned to his beloved home. Our history is so fascinating, but also so complex. Well written, Mr. Smith.