In 1923, the State of Delaware erected a statue to one its most famous sons in Wilmington, Delaware. The statue to Caesar Rodney showed him on his now famous ride to break the tie between the members of Delaware’s delegation to the Second Continental Congress. Rodney’s eighty-mile ride from Dover to Philadelphia to cast a vote in favor of Independence from Britain was Delaware’s most famous chapter in the history of the American Revolution. The ride signaled Delaware’s resistance to British oppression and the state’s dedication to Independence. The unofficial symbol of the State of Delaware is “The Ride.” Congressman Mike Castle worked to have Rodney’s likeness placed on the quarter representing Delaware. The Ride signs adorn roads up and down the state that help visitors find different housing developments and a high school even bears the name of Delaware’s most famous founding father.

Despite these celebrations for Rodney today, in the eighteenth century he was much more divisive. The citizens of Kent County punished Rodney politically for his stand on independence. The Dover native’s commitment to Independence is amazing when one considers the political situation of the colony of Delaware in 1775 and 1776. It was by no means a forgone conclusion that Delaware would follow Massachusetts and Virginia in formally calling for Independence. It was not even a forgone conclusion that Delaware would become anything more than the three lower counties of Pennsylvania. Of all of Delaware’s founding fathers, Caesar Rodney is the one most responsible not just for getting Delaware to declare independence from Britain but for getting Delaware to declare independence from Pennsylvania as well. The idea of independence was not a completely popular opinion in the most southern of Delaware’s counties. Despite Delaware figures in the American Revolution such as John Dickinson, John Haslet, and Thomas McKean, Rodney is the one who battled both to convince the colony of independence and to keep Delaware Loyalists from upsetting this independence.

Caesar Rodney was born on October 7, 1728 in Dover, Kent County, Delaware. When Rodney was seventeen, his father died leaving him under the guardianship of Nicholas Ridgley. The Ridgley family was prominent in Delaware and this prominence meant that Rodney would receive a classical education, attending schools in Philadelphia as a youngster. This classical education and prominent family connection meant that Rodney was destined for leadership roles within Delaware. Rodney became the Sheriff of Kent County and an assemblyman to the Delaware Assembly providing him experience as a politician. When the First Continental Congress sat in 1774, Rodney was a member of Delaware’s delegation along with Thomas McKean and George Reed. John Adams, upon meeting him, described Caesar Rodney as “the oddest looking man in world . . . slender as a reed—pale—his face not bigger than a large apple. Yet there is sense and fire, spirit, wit and humor in his countenance.”[1] Rodney suffered from various illnesses during his lifetime including asthma and facial cancer, which, after several medical procedures, left him with facial deformities that he hid behind a scarf. Caesar Rodney never married and had no children.

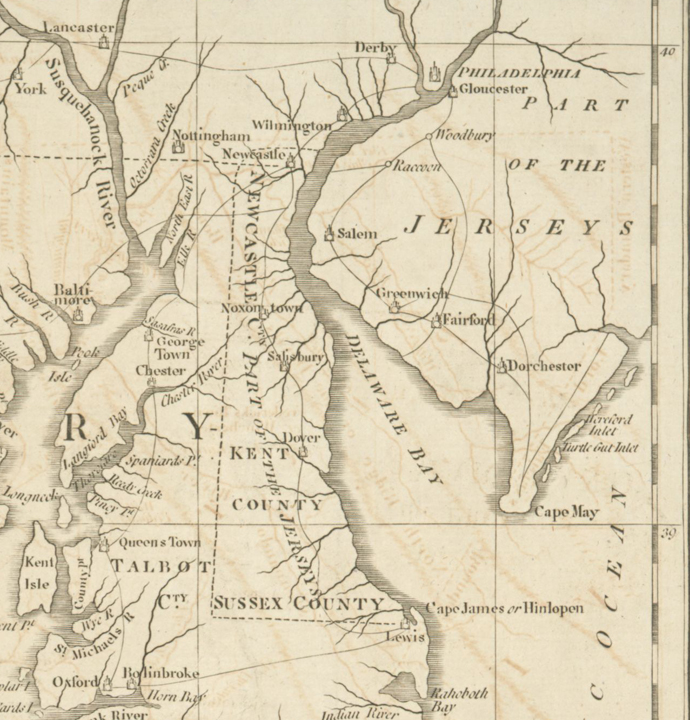

To understand Rodney’s contribution not just to the nation but to Delaware one must understand how Delaware came to be a state. In 1681, William Penn received a charter for the area known as Pennsylvania. Penn quickly realized that having access to the Delaware River and Delaware Bay would be crucial to the prosperity of the new colony. Penn quickly petitioned the Duke of York for control of the west side of the Delaware Bay. The west side consisted of three counties, from north to south, New Castle, Kent and Sussex. The King of England granted Penn a charter to these three Delaware counties in 1682 making Delaware a part of Pennsylvania. By 1702 Delaware was feeling neglected by the Pennsylvania Assembly and the Penn family. The continued settlement of western Pennsylvania angered many in New Castle, Kent and Sussex who saw their counties as being ignored. The colony of Pennsylvania granted Delaware their own legislative assembly in 1702. The two colonies shared a governor until 1776. John Penn, the grandson of William Penn was the last colonial governor of Pennsylvania and Delaware.

Caesar Rodney’s first step into becoming a founding father took place with his appointment to the Stamp Act Congress is 1765. This appointment was not without worry. The Delaware Assembly was in recess when word arrived of the organization of the congress. The Stamp Act Congress was illegal since Parliament and the King did not authorize it, and so the Delaware Assembly could not act in a legitimate manner and appoint representatives to this Congress; Governor Penn could never approve of calling forth the assembly to make appointments. Instead John Dickinson—a prominent landowner in Delaware, politician in Pennsylvania, and later called the Penmen of the Revolution—and others had a letter nominating three delegates drawn up and signed by officials in the three counties of Delaware.[2] Only Thomas McKean of New Castle County and Caesar Rodney of Kent County attended that Congress. The appointments came from the Delaware Assembly with the stipulations that they work to send petitions to King George III for redress against the Stamp Act.

The aristocratic Rodney and Scotch Irish McKean were markedly different. McKean was, from the start, a radical who threw himself into the work of the Congress. Rodney, although dedicated to the cause, was more reserved in his position toward the King. In a letter to his brother Thomas dated October 20, 1765 Caesar stated, “That in order to point out those grievances it was likewise necessary to set forth the Liberty . . . and was one of the most difficult tasks I ever yet undertaken, as we had carefully to avoid infringement of the prerogative of the crown.”[3] Both men supported and assisted in writing the declaration of rights sent to the King, which eventually led to the repeal of the Stamp Act in March 1766. The King received a letter of appreciation from Rodney, McKean and a prominent lawyer from New Castle County named George Read for the repeal of the Stamp Act.

These good feelings would not last long. In 1768, Parliament imposed the Townsend Acts, levying a tax on all glass, paper and tea brought into the colonies. The Delaware Assembly once again called upon Rodney, McKean, and Read, as the Committee of Correspondence, to write to the King expressing their right to tax themselves with their own assembly. The trio also criticized the decision to send those accused of smuggling to England for trial.[4] Rodney had not proven himself as a radical despite his work against taxation by Parliament. His good relationship with Governor Penn tarnished his radical credentials.

With the repeal of the Townsend Acts in 1771, political fervor against Britain calmed in Delaware. This changed with the British attempt to monopolize tea in the colonies by giving the exclusive right to sell tea to the British East India Company. The Tea Act passed by Parliament in 1773 led to boycotts around the colonies. Thomas Rodney expressed the sentiments of many in Delaware when wrote, “This diabolical measure, like another Electric Shock.”[5]

Despite some ill health that included treatment by bloodletting, Rodney was elected to the Delaware Assembly and was chosen by that body to be the speaker.[6] In October 1773, as Speaker of the Delaware Assembly he responded to the Virginia House of Burgesses stating that Delaware had created a Committee of Correspondence. This Committee included Rodney from Kent County, Thomas Robinson of Sussex County, and Thomas McKean, George Read and John McKinley all of New Castle County. Rodney, McKean and Read were the most active members of the Committee. Each county even went so far as to establish their own Committees of Correspondence, again with Rodney taking the leading role in the Kent County group. The Committee of Correspondence organized and led protests in support of Boston in each of the three counties.

Delaware was not immune to the events heating up the American Colonies against the British. The event that led to the eventual downfall of the British in the colonies was the passage and implementation of the Coercive Acts. The Intolerable Acts, as the colonists knew the Coercive Acts, was a series of measures, which included the closing of the port Boston. The Tea Act and the closing of the Port of Boston led many including Caesar Rodney to become much more militant. The Delaware assembly under the leadership of Rodney immediately denounced the Acts. On May 25, 1774 Rodney, Read, and John McKinley, members of Delaware’s Committee of Correspondence, wrote to Virginia pledging support for Massachusetts and the idea that an attack on one colony would be an attack on them all.[7] In June, in an effort to publicly support Boston Rodney helped to organize rallies in all three Delaware counties. Rodney was never a prominent public speaker at any of these rallies probably due to his facial disfigurement; instead he deferred these speaking duties to Thomas McKean. In the fall of 1774, at the suggestion of Continental Congress of which Caesar Rodney was a member, Kent County formed a Committee of Inspection and Observation to investigate actions against the patriot cause.[8] Rodney in his leadership role in the Assembly was creating a stir in Delaware against the British and their policies.

In July 1774, Rodney, as Speaker of the Delaware Assembly, had called for a committee to choose delegates to the First Continental Congress. At the August 1 meeting, the Assembly chose Rodney to represent Kent County, and Thomas McKean and George Read to represent New Castle County. Speculation exists that Thomas Robinson, a prominent landowner and storekeeper in Sussex County, was the chosen delegate from Sussex County but refused to accept due to his opposition to the Congress that he saw as illegal. The delegates were instructed, “to avoid everything disrespectful to King George III.”[9] Maybe even more importantly for the lower three counties of Pennsylvania was that they got an equal vote in the Continental Congress just like every other colony. Delaware’s first step toward independence had just taken place, under Rodney’s watch. The First Continental Congress created two committees and choose Rodney as one of twenty-four men to be members of a committee that would report on “the Rights of Colonies, the infringements of those Rights and the means of Relief.”[10] The delegates then had to deal with the thorny issue of the Suffolk Revolves, a condemnation of the Intolerable Acts that declared those acts by Parliament unconstitutional and called for the organization of a militia. Rodney by this time was an ardent patriot and accepted the Suffolk Resolves with little hesitation. Looking at the letter he wrote to his brother Thomas dated September 17, 1774, Rodney seems so unconcerned about the decision of the Continental Congress that he failed to even mention their decision to his brother. He mentioned only that Thomas would see the decision in the newspapers.[11]

In March 1775, the Delaware Assembly again turned to Rodney, McKean, and Read to represent them in the Second Continental Congress. They were again told to avoid “everything disrespectful or offensive to our most gracious Sovereign.”[12] An unsigned letter from a Kent County resident appeared in the Pennsylvania Ledger which stated, “I believe, if the King’s standard were now erected, nine out of ten people would repair to it.”[13] The situation the three delegates found themselves in was a precarious one not just in regards to Britain but at home as well. On May 25 members of the Kent County militia met in order to organize and establish discipline. Rodney and John Haslet were named colonels of the two regiments and all the officers signed an oath to “defend liberties and privileges of America.”[14] Throughout this period, Rodney worked not only in the Continental Congress but also in Delaware organizing and equipping members of the Delaware Militia. Loyalist or Tory activity in Delaware also began to increase during this period. Thomas Robinson, whom historian Harold Hancock has called “the state’s most prominent loyalist,” began to increase his criticism of the patriots in Delaware and openly disregarded the boycott of British Tea. [15]

In May 1776, the Second Continental Congress passed a resolution asking that each of the colonies cut ties with Britain, marking a first step toward national independence. On June 7, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution in Congress declaring, “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be free and Independent states.”[16] Rodney, as Speaker of the Delaware Assembly, quickly took action on June 15 by having Delaware sever all ties with the Crown including the proprietary governor, John Penn. The cutting of these ties with the Royal Governor became known as Separation Day in Delaware. Delaware had cut ties from Britain and Pennsylvania.

Petitions began circulating from both those in favor of Delaware creating a new state government and those Tories who were opposed to such action. Tories in Sussex County gathered 1,500 men under the direction of Thomas Robinson. This group contacted Royal Navy Capt. Andrew Snape Hammond, whose vessel, HMS Roebuck, was anchored in the Delaware Bay. The group hoped to get arms and ammunition but Hammond soon reported that he did not have supplies to spare. There is some thought that Hammond was unsure of the number of Tories in Sussex County and was hesitant support an uprising that would be unsuccessful.[17] Eventually three thousand Pennsylvania militia went to Sussex County to quell the uprising. In the lower two counties accusations and debates swirled as both Whigs and Tories worked to get signatures for their petitions. Rodney worked tirelessly sending letters and speaking with groups about the need for people to support the Whig position.

On June 9 Tories led by Richard Bassett, Thomas White, and John Clark, all large landowners in Kent County. devised a plan to attack Dover, burn it to the ground, and then deal with all Whigs harshly. Rodney worked quickly to squash the uprising with the help of Col. John Haslet. Rodney had the area placed under Whig guard and had Bassett arrested. Local clergy acted as mediators between the Tory and Whig leaders, who had gathered a sizable force, to bring peace back to Kent County. The incident came to be known as Black Monday.

During this time between Lee’s Resolution of June 7, 1776 and the ratification of the Declaration of Independence, Rodney worked to control Tory sentiment within Delaware. Col. Allen McLane fixed 1776 as the time for decisions, stating, “At this time the line was drawn between Whig and Tory.”[18] Rodney was in almost constant contact, at least in eighteenth century terms, with Colonel Haslet, commander of First Delaware Regiment. The two Patriots moved Delaware militia around Kent and Sussex County in an attempt to control uprisings and potential riots among Delaware’s Loyalist Tory population. On June15 the Delaware assembly finally gave the delegation to the Second Continental Congress instructions to vote as they wished instead of trying to reconcile with Britain.

Caesar Rodney’s most memorable contribution to Delaware and the fledgling nation was his ride to the Pennsylvania State House to break the tie among his fellow delegates from Delaware on the issue of independence. Rodney, as a brigadier general in the Delaware militia, decided in late June to leave Philadelphia and return to Delaware due to uprisings in Sussex County over the issue of independence. The Sussex County Council of Safety reported that those involved in this Tory activity were, “a more dangerous enemy than the Europeans.”[19] On July 1 the Lee Resolution calling for independence was brought to vote in front of the committee of the whole in Philadelphia. Only George Read and Thomas McKean were present as representatives from Delaware when the vote came up. McKean, the fiery radical, immediately voted in the affirmative for the motion. Read, a longtime friend of John Dickinson who was a proponent of delay in calling for independence, had kept relatively silent about his thoughts on the matter but voted against the measure. An angry McKean quickly, at his own expense, sent off a message to Rodney asking that he immediately come to Philadelphia to vote for independence.

Around midnight this messenger found Rodney in Dover; upon reading the message Rodney quickly left the city for Philadelphia; it is uncertain whether he took a carriage or went on horseback, although it seems likely that he used both to complete the vigorous eighty-mile journey. Rodney rode through the rain, thunder, and crossed no less than fifteen streams and rivers to get to the Pennsylvania State House. Attired in spurs, mud-splattered, ill and exhausted, Rodney dismounted his horse. McKean, who had been watching intently out the window, met Rodney at the door of the State House. When the clerk of the committee of the whole called on Delaware to register their vote for independence, Rodney rose and stated, “As I believe the voice of my constituents and of all sensible and honest men is in favor of independence, my own judgement concurs with them. I vote for independence.”[20] The sick and exhausted patriot slumped back into his chair. His vote galvanized support for Independence within the Second Continental Congress. South Carolina changed its vote and supported Independence due to Rodney’s ride.[21] John Dickinson stayed away from the vote altogether, allowing the rest of Pennsylvania’s delegates to vote for independence. These events eventually led to a twelve-zero vote in favor of independence from Britain with only New York abstaining.

As news of independence spread, celebrations erupted around the, now, State of Delaware. Lewes saw Colonel Haslet’s regiment fire three cannon shots and drink three toasts. Five hundred Patriots gathered in New Castle to hear a reading of the Declaration of Independence. In Dover, Rodney’s brother led a group of light infantry in celebration on the green. The group found a portrait of King George the III, lit a bonfire and tossed it into the fire. Thomas Rodney also called for an investigation into the petition that the Tories had set forth calling for loyalty to Britain. Caesar Rodney opposed this idea; considering the numerous loyalists in the area it was probably a safe decision and he counselled his younger brother to calm his rhetoric.

Rodney, the speaker of the Delaware Assembly, on his return to Delaware called for a constitutional convention for the state. The assembly asked each county to pick ten delegates to the state’s constitutional convention. Due to the overzealousness of Rodney’s brother Thomas, the Whig party including Caesar Rodney lost their chance at re-election. Tories were overwhelming elected to this constitutional convention from Kent County leaving Rodney, the leading patriot in Delaware, on the outside looking in. In Sussex County, the Whigs and Tories each elected a group to the convention. Since the leadership of the convention was moderate, the Tories were seated in the convention. Caesar Rodney was furious with his brother over this turn of events. All of the hard work that he and fellow patriots had put in was now on the verge of being lost. The Delaware Constitutional Convention fell into the hands of more moderate members. The presiding officer for this Convention was George Read, the very delegate who did not initially support the Declaration of Independence and only reluctantly signed it later due to his worry over his future in Delaware politics. By November 1776, the Delaware General Assembly had Rodney and McKean removed as Delaware’s delegates to the Continental Congress. The Delaware Assembly selected conservatives John Dickinson and John Evans as the new delegates. The new state constitution and overall state government of Delaware were in the hands of conservatives or moderates. In September 1776, Delaware had a new state constitution. This was the first such document in the U.S. written “by a body elected for that purpose.”[22]

Despite all of Rodney’s successes and his devotion to the cause of liberty citizens within his own state were not happy with his leadership. Delaware overall was a conservative colony and calls for independence were not looked at in a favorable light by many. Kent and Sussex counties both tended to be more isolated and rural than the rest of the colony. In addition, these lower two counties saw a strong presence of the Church of England and were in close proximity to the Delaware Bay, where prowling British ships frequently stopped and contacted the strong loyalist presence within the lower two counties. Captain Hammond of Roebuck was on duty in the Delaware Bay in 1776. He wrote to his superior officer, “I have the pleasure to inform you that the inhabitants of the two lower counties on the Delaware, tired of the tyranny and oppression of the times, have taken up arms to the number of 3,000 and declare themselves in favor of (the British) government.”[23] The loyalist presence in these areas was undeniable and at times violent.

Rodney’s work toward independence for Delaware was beyond reproach. When one looks at his contemporaries, we begin to see how Rodney separated himself from the others. George Read was a moderate who refused to embrace independence until absolutely forced to do so. John Dickinson was more of a Pennsylvanian and always supported a conciliatory attitude toward Britain. Col. John Haslet is famous more for his military deeds then for his work for moving Delaware toward independence. Ann Decker in her thesis makes the contention that the two brothers together, Caesar and Thomas, deserve credit for Delaware’s and the nation’s independence. However, this argument is incompatible with the facts. Thomas never held the prominent national positions that Caesar held. Thomas was also too much of a hothead who made some key mistakes that luckily did not stymie independence in Delaware. He refused to recognize that parts of Delaware were not going to go quietly into independence. Caesar himself recognized this, admonishing his younger brother, “and you may also take for granted every Body here are not well pleased with the coalition of the two Brothers.”[24]

The only one of his peers that comes close to equaling Caesar Rodney’s place among Delaware’s founders is Thomas McKean. However, McKean, like Dickinson, liked to play in the bigger pond of Pennsylvania. He established permanent residence in Philadelphia in 1773. It is also hard to see whether McKean alone, the Philadelphian and New Castle County resident, without Rodney’s assistance could have brought the lower two counties around to independence. His ties to Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in general coupled with his learned lawyerly ways would not necessarily have gone over well with Kent and Sussex County residents. Throughout 1775 and 1776, McKean spent an incredible amount of time working on bringing the Pennsylvania assembly around to the idea of independence. At times, he served the dual role of Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and a Delaware Official. When McKean died, he was buried in Philadelphia, not exactly a tried and true Delawarean.

Caesar Rodney, despite illness, fatigue, and threat to life battled friend and foe alike to see that Delaware was independent. He died in June 1784, a mere nine months after the signing of the Treaty of Paris formally ended the Revolutionary War. Rodney was able to live long enough to see the full fruition of his earlier work. What might have happened had Rodney not worked to secure independence for Delaware? One would have to think that the revolution as a whole might have been put on an even more dangerous footing had it not been for Rodney keeping Kent and Sussex Counties in line. With loyalist control of Delaware, would the Delaware Bay become a haven for British ships? How would Philadelphia have faired had the Delaware Bay been in the hands of the British? Alternatively, would Delaware have become a major resupply center for the British? What if the gunpowder mills of Delaware had fallen into British hands or the corridor between Baltimore and Philadelphia was controlled by the British? The outcome of the Revolution would have been left in doubt had it not been for Rodney. Delaware without Caesar Rodney at the helm during these tumultuous times may have fallen into chaotic disarray. Charles E. Green in his book The Story of Delaware in Revolution ends his brief biography of Rodney by saying, “Caesar Rodney was unwavering in his services to Delaware and the Nation . . . On his crown of glory, shinning in undimmed splendor, are the precious jewels of fidelity to duty, unassailable integrity, and dauntless patriotism.”[25]

On June 11, 2020 around 8 p.m., the statue of Caesar Rodney erected in 1923 came down. Tumult surrounding race in the United States and Rodney’s ownership of some two hundred enslaved people on the plantation just south of Dover named Byfield caused city officials to place his statue in storage amidst further discussion on the issue of race. Like Thomas Jefferson, Rodney’s ownership of enslaved people has tarnished what would otherwise be a great legacy to Delaware and the nation. Unlike Jefferson, Rodney’s will called for the immediate emancipation of some of his enslaved people and the eventual emancipation of the rest. Rodney opposed the importation of slaves but he never seemed to question the institution itself. Like Washington and Jefferson, Caesar Rodney is in this regard a difficult founder to come to terms with. Should the work he did to make the United States what it is today be celebrated, should he be condemned for participating in an immoral and barbaric institution that was accepted during his life? Rodney has left an indelible mark on Delaware and the nation’s history. The hope is that one day we can find the happy medium where we interpret and reflect on these men as flawed individuals, still worth celebrating for their crucial and everlasting accomplishments.

[1] David G. McCullough, John Adams (Alexandria, VA: Alexandria Library, 2008), 86.

[2] Jane Scott, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig: Caesar Rodney and the American Revolution (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2000), 34.

[3] George H Ryden, ed., Letters to and from Caesar Rodney, 1756-1784: Member of the Stamp Act (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1933), 26.

[4] Scott, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig, 39

[5] Harold Bell Hancock, The Loyalists of Revolutionary Delaware (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1977), 16.

[6] Scott, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig, 55

[7] Harold Bell Hancock, Liberty and Independence: The Delaware State during the American Revolution (Wilmington: Delaware American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, 1976), 68.

[8] “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, 1775,” www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/lord-dunmores-proclamation-1775.

[9] Charles E. Green, Delaware Heritage: The Story of the Diamond State in the Revolution (Wilmington, DE: Press of W.N. Cann, 1975), 19.

[10] Ryden, ed., Letters to and from Caesar Rodney, 47.

[11] Ibid., 47.

[12] Scott, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig, 81.

[13] Ibid., 82

[14] Ibid., 87

[15] Hancock, The Loyalists of Revolutionary Delaware, 9.

[16] “Lee Resolution (1776),” www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/lee-resolution#transcript.

[17] Timothy J Wilson, “Old Offender: Loyalists in the Lower Delmarva Peninsula 1775-1800,” Thesis, Univeristy of Toronto, 1998, 141.

[18] Hancock, The Loyalists of Revolutionary Delaware, 40.

[19] Dick Carter, The History of Sussex County (Millsboro, DE: Self Published, 1976), 15.

[20] Scott, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig, 118.

[21] John A. Munroe, Colonial Delaware: A History (Wilmington: Delaware Heritage Press, Delaware Heritage Commission, 2003), 226.

[22] Scott, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig, 123.

[23] Michael Morgan, “Delaware’s Most Prominent Loyalist,” Sussex Journal, April 25, 2017.

[24] Scot, A Gentleman as Well as a Whig t, 76.

[25] Green, Delaware Heritage, 46.

One thought on “The Indelible Caesar Rodney”

Thanks for helping to highlight the critical role of Delaware in the Revolution.

There has been considerable speculation, as you may have found, about why Rodney was lingering in Dover rather than being on hand in Philadelphia for the vote. The most likely reason was that the man must have been exhausted and in need to some personal recovery. He had been in Lewes in Sussex County quelling the possibility of a Tory insurrection in late June. The following is a quote from Howard Hancock, ed., The Revolutionary War Diary of William Adair.” Delaware History 13 no. 2 (October 1968), 156. “June 19-20. Col Rodney came to try Tories with 1000 Men Viz Haslet’s Batalion [sic] – also a Fair Representation of Riflemen to Reduce a Tory Insurrection here-Witnesses examined for 4 Days-Tories ordered to bring in their arms and ammunition.”

Leaving Lewes on June 24 gave him only a week to be in Philadelphia but he probably wasn’t worried not suspecting that Read would be indecisive and have temporary second thoughts.