Transitioning from a complicated war footing to an organized civil society at the close of the Revolution proved every bit as difficult as the nation’s early leaders feared. Thirteen proud colonies surrendering aspects of their hard-fought independence in exchange for a new form of federal government generated significant hesitancy after the guns silenced. The placeholder Articles of Confederation (1781-1789) provided some assurance of order at first, but hardly as well as the Constitution did when it took center stage.

As a result, the entire rule of law practiced throughout the new-found states changed virtually overnight, including the state admitted into the fold in 1791, Vermont. In the rush to accommodate the demands made by fledgling federalism in this historically tumultuous region, one of its first leaders, Gov. Thomas Chittenden (1730-1797), soon fell victim to the changed legal landscape. Upon suffering the indignity of being compelled to appear in a newly created federal courtroom in 1797 to go before a jury of his peers, charged with committing a federal offense, he faced immediate imprisonment upon their finding of guilt, only to escape that fate by dying soon after; the only governor among eighty-two others in state history to experience such an ignoble end.[1] His offense? Selling alcohol without a license and allowing its consumption in an unlicensed establishment.

That Chittenden ran afoul of the law in such a seemingly innocent way could not have surprised anyone who knew him. Greatly admired, his solid, pragmatic political reputation preceded him for more than two decades of public service, including as governor overseeing the region’s coalescence and admission into the Union as the fourteenth state. At the same time, Chittenden was also well-known among his peers for his hail-fellow-well-met, bon vivant bearing. A surviving document titled “Wine Account for the General Assembly of 1787” provides ample evidence of the copious amounts of alcohol “His Excellency Gov. Chittenden” and other politicos consumed in their work environment.[2] Now, in the physically weakened autumn of his life, instead of basking in the glow of his accomplishments among friends, he faced the conviction for a federal crime for his alcohol-infused gregariousness, penalized for doing what so many others did.

The question for modern students of those times is why has this information of Chittenden’s stumble not been revealed until now? Why did those in positions of power and a probing press at the time, each knowing full well of his problem, fail to publicly acknowledge or report it? For answers, it is necessary to inquire into not only the context of these turbulent times, but also the extant Vermont federal court records housed at the National Archives and Records Administration in Boston pertaining to Chittenden and some of his constituency receiving similar convictions.[3]

In the process, it is worth remembering that “history records what people do, rather than what they are.”[4] Reserving judgment on Chittenden’s personality, these documents will, with reasonable certainty, allow us to reconstruct what happened to finally reveal a missing part of that long-ago story.

Background

Following the end of the Revolutionary War and settling the lingering border dispute with New York, the recognition of Vermont as a state in 1791 meant the sudden introduction of federal laws and accompanying institutions into the Green Mountains, changes embraced by its inhabitants with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Foremost were those provisions surrounding the collection of revenues to fund the new nation’s infrastructure, assure its operations, and retire its significant debt incurred fighting the war. Accordingly, customs laws and a supervising collector and his deputies gathering fees and operating customs houses suddenly appeared across the landscape. They worked zealously to bring malefactors before newly created federal judges presiding in district and circuit courthouses in Burlington, Rutland, and Windsor. They were backed up by a US marshal and his deputies, alongside bailiffs and clerks, solidifying an all-too-real federal presence in the state.

The will of strong-minded advocates of a national government, called Federalists, overlaying this new legal system across the existing, domestic one that independent Vermonters, including Chittenden, had already become familiar with, presented its own unique challenges. Unaware of the disruptive changes awaiting them, some gathered on the eve of statehood in Rutland to celebrate. Their revels were attended by esteemed legal illuminati, including: “judges of the supreme federal court, the attorney general and other officers of the court.” Then, to the sound of booming cannon, the assemblage raised their glasses in recognition of a new dawn. Making a series of rousing “federal toasts,” they praised “his excellency governor Chittenden,” prayed that “federal officers . . . act with integrity and merit the confidence of the people,” and wished that “may we never experience a less happy moment than the present under the federal government.”[5]

The timing of these events coincided precisely with those taking place only a few hundred miles away in Pennsylvania. There, violent opposition rose up against the same federal government that Vermonters welcomed. Indigent frontier settlers deeply resented the government’s recent imposition of the Tariff of 1791 imposing an excise tax on the large quantities of spirits they distilled, with great difficulty, from their abundant grain crops. Their steady opposition soon escalated into the Whiskey Rebellion (1791-1794) that President George Washington was forced to send thousands of troops to quell. The response further prompted the government’s prosecution of dozens of farmers for treason; an effort many viewed as heavy-handed overstepping, a trampling of the downtrodden by the powerful.

How national leaders handled the Pennsylvania problem generated significant interest in Vermont. Increasingly, after the arrival of federal personnel in 1791, the laws they enforced seemed to appear overnight. In addition to their courts, in May 1793 revenue officials established offices in each of Vermont’s counties. They required their inhabitants to license every still producing spirits they operated, and assessed unwelcomed fees on each, with fines for violators.[6] These early, unpopular efforts to support the young federal government with its intrusive laws soon tested Vermonters’ tolerance for them and provide an important backdrop to Governor Chittenden’s own impending legal problems.

Revenue Woes

Nobody likes to pay taxes. Vermont, of course, is endowed with an international border separating the United States from Canada, then also known as British North America. The onus of paying the customs duties for goods crossing south from Canada fell principally on local Vermont importers. While the law initially imposed only modest duties on their shipments of alcohol (i.e., five cents for a gallon of beer, ten cents for Jamaica proof spirits, eighteen cents for Madeira wine, etc.), they became more burdensome, doubling on the heels of Pennsylvania’s rebellion.[7] Only days before Chittenden’s breach of the law in March 1796, the Democratic Society of Rutland expressed concern about the effects these duties imposed on those living in the northwest part of the state, including in Williston where Chittenden lived. The duties were onerous, the society said, forcing honest merchant-retailers to shoulder an unfair monetary burden passed on to them by their suppliers, but which their smuggling neighbors could avoid. As a result, it placed the honest retailer in an untenable position of having to “constantly account to his customers for a higher price of his goods.”[8]

Honest retailers were also required to purchase licenses from customs officials, costing $5 a year. In the government’s eagerness to ease the flow of alcohol to generate needed income, the law made generous provision allowing virtually anyone to obtain a pre-signed license from Vermont’s supervising collector of revenue or any of his five auxiliary officers. Then, after receiving alcohol in bulk casks from their importers or wholesalers, the licensed retailers could sell it in smaller quart and pint quantities from their licensed taverns and inns. It could be consumed either on the premises or taken away as the customer desired. Those failing to obtain the necessary license to sell faced a $50 fine and paying the costs of prosecution.

The first revenue officers in the Green Mountains did not face serious challenges to their authority in the months following statehood. But on December 17, 1792, at “Bason Harbor” on the east shore of Lake Champlain, where officials stored seized casks of illegally imported spirits, the first recorded, coordinated attack against federal authorities took place. Perhaps because of its remoteness and insufficient number of officers guarding the casks, the assault marked Vermont as an outlier among its New England neighbors. None of the records of the federal courts for Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, or Rhode Island, where a denser population lived along the Atlantic seaboard and a more robust federal presence existed, reveals a single instance of such violence against revenue officials throughout the 1790s.

In response to the attack, Vermont’s new federal district court held its first “special term” convening in Burlington by order of recently-appointed Federalist judge Nathaniel Chipman. The term was commenced in May 1793 with the swearing in of a fourteen-member grand jury. Six men from Vermont and New York were quickly indicted for their roles in the attack. They were charged with violently removing two casks of spirits (“with force and arms”), containing thirty-seven gallons each, valued at $200 out of the custody of two revenue officers, and then “secreting” them from discovery.[9] Thereafter, between 1793 and 1795, the courts’ records reflect a period of relative calm. In Washington, Congress passed two new laws (effective June 1794) strengthening the government’s grip on alcohol-related issues, outlawing the unlicensed sale of wine and spirits, provisions that came into play in Chittenden’s case.[10]

By February 1796 the escalating violence in Pennsylvania, where hundreds of rioters set fire to the regional revenue collector’s home, alarmed Vermont’s second federal district court judge, Federalist Samuel Hitchcock (soon to oversee Chittenden’s prosecution). Hitchcock feared similar conduct in the Green Mountains, possibly even exceeding the violence that had occurred at “Bason Harbor” two years earlier. To ward off such a prospect, in welcoming a newly-empaneled grand jury in Windsor, he told it to vigorously protect the new federal government’s interests by enforcing its revenue laws. Initially, he acknowledged that “Hitherto there has been but little business before this Court,” attributed, he “hoped,” to “the virtuous and orderly disposition of its citizens.” But then he pragmatically acknowledged the inclinations of some of them to use the increased forms of violence seen in Pennsylvania. Wishing that “exemplary punishment” might rain down on such offenders, he urgently instructed the grand jury, with palpable concern, to “Let no character feel himself above the law” in bringing charges against them.[11]

It is not surprising, then, that between 1797 and 1799, prosecutions for the unlicensed sale of alcohol in Vermont escalated dramatically. Authorities brought forty-nine defendants before the district and circuit courts in that short period of time. While the specific number of others operating outside of the law is unknown, the name of “Thomas Chittenden, Esq.,” as he is notably identified in the court’s papers, ranks among the first snagged by vigilant customs officers headed by Supervising Collector Stephen Keyes (Federalist). Chittenden’s alleged transgressions were then brought to the attention of newly-appointed prosecutor District Attorney Charles Marsh (Federalist) in the spring of 1796.

Offenses

The heavy drinking that Chittenden and his friends engaged in during the legislative session seems to have continued unabated at his home in Williston. One history describes him (in a coded manner) as someone who “enjoyed the fellowship and love of his friends and neighbors.” He was “particularly noted for sociability and hospitality, his house being at all times open to the ever-welcome guest.”[12] Other watering holes like the one at Chittenden’s home existed throughout the county. They probably operated in the same informal manner, selling alcohol without a license. In 1796, only 49 licenses to sell wine and 187 for spirits were issued statewide, generating a measly $1,180 for the national treasury.[13] In a state notorious for its alcohol consumption, sales of wine and spirits were clearly taking place outside of those few licensed outlets servicing a population of 154,465 in 1800.[14] Records reveal that in 1801, Chittenden County officials identified 34 licensed inns operating within their bounds among the 489 doing so statewide.[15] Some obtained the necessary licenses to sell alcohol, but not all did.

There was always an undercurrent of lawlessness surrounding the enforcement of federal alcohol revenue collection efforts in these years because manpower was spread too thin around the state. Lax enforcement continued after Chittenden’s misstep in 1796, leading up to 1808 when two militiamen attempting to enforce the revenue laws were killed by smugglers in an alcohol-infused ambush (the Black Snake Affair) on the Onion River downstream from his home.[16] But in 1796 Chittenden’s transgressions would have been commonplace.

According to court papers, on March 1, 1796, Chittenden committed two offenses, one concerning the unlicensed sale of wine and the second involving allowing the consumption of spirits on his unlicensed premises. The quantity involved was sizeable: ten gallons of wine distributed in quart and gallon containers and two gallons each of French Brandy, West India Rum, and Holland Gin dispensed in the same manner, sixteen gallons in total. No one can say today what occasioned this well-lubricated event.

The timing of it coincides with the topsy-turvy Democratic-Republican run-off election cycle taking place between December 1795 and February 1796 for the US House in Vermont’s western district that included Chittenden County. The outcome of that election was not known at the time with candidates Matthew Lyon (his son-in-law) and Israel Smith swapping leads. From the opposing political party, Federalist Judge Hitchcock’s name was also in the mix, but he ultimately came up short when Lyon won out.[17]

Thereafter, the timing of events surrounding Chittenden’s prosecution offers undertones of political payback, possibly related to the election results. His democratic-republican sympathies may have prompted those stern instructions made by the law-and-order Hitchcock in February to the grand jury advocating for rigid enforcement of the liquor revenue laws so that “no character” could “feel themselves above the law.” Aside from the prospect of violence presented by increasingly bold smugglers and those intent on disrupting the work of revenue officers, his comments could also have been intended as a shot across the bows of Chittenden and his friends.

Prosecution, conviction, sentence

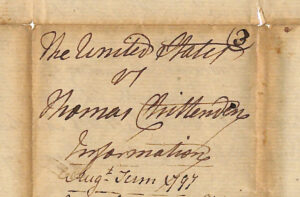

Proceeding by “Information” (thereby bypassing the need to present evidence before a grand jury as used in similar prosecutions) and using the same boilerplate language appearing in other violators’ paperwork, that pertaining to Chittenden was filed by prosecutor Marsh with Judge Hitchcock, sitting in Rutland, on May 15, 1797, more than a year after Chittenden’s alleged missteps. The reason for this delay is uncertain, but we do know that the sixty-seven-year-old governor’s health was already in decline at the time. In February 1797, Chittenden either wrote, or dictated, a one-page letter to his lieutenant governor, Paul Brigham, to advise that he had been confined to his home for the preceding fortnight making him unable to attend the approaching legislative session. He was suffering, he explained, from the effects of “an extraordinary cold.”[18]

Perhaps acting with speed because of Chittenden’s health, Judge Hitchcock immediately accepted Marsh’s allegations. Just days later, on May 20, he summoned Chittenden to appear in his Windsor court “on the first Monday of August next” to attend trial. However, Deputy US Marshal Samuel Fitch did not serve the summons on Chittenden until July 21. As Fitch noted on its reverse, he did so by leaving a copy of it at “the dwelling house of the within named Thomas Chittenden, Esq.” in Williston.

Despite Fitch’s delay, Chittenden must have been aware of the summons beforehand. Subpoenas issued by Hitchcock on July 1 and 20 commanding the presence of several noteworthy witnesses at trial to provide testimony “in behalf of the United States” could not have escaped his knowledge. They were Chittenden’s associates and friends and included: Federalist Solomon Miller, Esq. (Chittenden County justice of the peace appointed by Chittenden and probate court judge); Jonathan Spafford (Williston representative); Joshua Stanton, Jr. (attorney, Colchester town clerk and assistant county judge); and Amos Brownson (Richmond justice of the peace and former Williston representative). But did they actually appear? Did any of them testify? If so, did their testimony concern witnessing Chittenden’s transgressions or were they willing participants themselves? Could politics have influenced their testimony in any way? Were there additional witnesses whose names did not survive in the court’s paperwork? There are no transcripts of the proceedings, so we do not know.

In an undated entry, and with Hitchcock’s approval, attorney Daniel Buck (Federalist) made his appearance on Chittenden’s behalf, entered not guilty pleas to the two counts and placed his client’s fate in the hands of a jury (or, in the period vernacular, “puts himself on the country”). The experienced Buck was a Revolutionary War veteran who saw action at Bennington in 1777, where he lost an arm. The injury did not hold him back from advancement. He was involved in several pivotal moments in the state’s formation, served as its second attorney general (succeeding Hitchcock) and, just two months before assuming Chittenden’s representation, on March 3 ended a two-year term as Vermont’s representative to the U.S. House of Representatives.

In July 1797, facing mounting pressure from his prosecution and health, Chittenden penned his only public statement about his plans not to seek continued public office. While many in Vermont’s power structure at the time were aware of the charges he was facing in Hitchcock’s court, they remained silent. Neither was there any press coverage of them, while Chittenden was similarly silent. As an unfortunate result, in toto, they allowed the letter’s representations to stand alone, lacking context omitting the trial’s importance thereby leaving a gaping hole in the historical record.

Despite its open-ended date of “July 1797,” Chittenden’s de facto resignation letter first appeared on August 4, three days before the trial commenced, in Spooner’s Vermont Journal, published in Windsor where the trial unfolded. The letter omitted any mention of the impending trial. Neither did the newspaper’s editor mention it, thereby allowing him to graciously end his many years of public service without further comment.[19] No doubt “Impaired as I am, as to my health,” he wrote, it was the sole reason he identified “to decline being considered as a candidate” at the next election. Thanking his constituency for their past support, he asked them to choose someone other than himself.

Chittenden’s court papers provide no direct information about the conduct of the trial itself, relating only that it occurred over the course of a single day, on August 7. A brief entry regarding the jury’s verdict, signed by local storekeeper foreman Allen Hayes, states simply that it found Chittenden “guilty of the first count [selling ten gallons of wine] and not guilty of the second count [selling six gallons of spirits].” Whereupon, in accord with the applicable statute, Judge Hitchcock sentenced Chittenden “to pay a fine to the Treasury of the United States of Fifty Dollars and the costs of prosecution taxed at sixty one dollars and seventy nine cents.”

No doubt shaken by the jury’s verdict and sentence, as well as his health, Chittenden sought to excuse himself from attending any further proceedings. Accordingly, the following day Buck requested of the court that his client’s “personal appearance . . . be dispensed with & he be allowed to proceed by attorney.” Hitchcock granted the request. Buck then moved for a “new tryal” arguing that the jury’s verdict was wrongfully imposed because it believed the law allowed the Secretary of the Treasury to remit, or negate, the finding of guilt and/or the fine. Correcting that misinformation, he explained that no such provision existed and that “the jury have mistaken the law in this case,” rendering its verdict invalid. Motion denied.

Four days later, on August 12 Hitchcock ordered US Marshal Jabez Fitch to seize $111.79 of Chittenden’s property to pay the fine and costs. Should Fitch be unable to find such assets, he was further “commanded to take the body of the said Thomas and him commit to the keeper of the gaol in the City of Vergennes . . . who is hereby commanded to receive the said Thomas within the said gaol and him safely keep until he pay [the penalty] with your fees, or otherwise be discharged by order of Law.”

It soon became impossible for Fitch to fulfill the order because Chittenden died quietly in his sleep on August 24 or 25 (inconsistent dates are cited).[20] Marking the document “wholle unsatisfied” on September 13, Fitch wrote that “before I had time . . . [to execute it] Thomas Chittenden departed this life.”

Conclusion

Thomas Chittenden is the only governor in Vermont’s history to be convicted of a crime committed while in office. Those unsettled first years of statehood brought myriad newfound challenges for many: new federal laws, new federal institutions, and uncertain enforcement mechanisms creating a legal landscape difficult to navigate. The changes affected even those with the best intentions, regardless of rank or position, including himself. It may be that Chittenden was specially targeted for prosecution by those with federalist intentions (i.e., Judge Hitchcock, Collector Keyes, and District Attorney Marsh) because of his democratic-republican leanings. Were they fearful that if he went unpunished, violence against revenue officials would increase as it had in Pennsylvania? If he was meant to serve as an example to other licensing scoff-laws, then why was information about his offense suppressed? Could the federalists have realized, too late, that they had overplayed their hand against an accommodating elder statesman held in high regard and in a weakened state commanding sympathy instead? Or was Chittenden simply caught up, like his neighbors, in their frenzy committing seemingly inconsequential violations of the revenue laws marking this important man as undeserving of public condemnation? The current evidence is silent on all points.

When he was housebound with illness in February 1797, unable to attend the upcoming legislative session, Chittenden temporarily passed the baton to Lieutenant Governor Brigham: “You will therefore of course,” he counseled, “take my place, put on the fortitude of a man and conduct the business to the best advantage in your body.”[21] He recovered only briefly after that, turning to face his tormentors in his last days. Then, after experiencing the indignity of having his reputation besmirched by a jury of his peers, his body quietly gave out. Choosing to ignore the circumstances of that last, sad chapter in his life, the press respectfully announced his passing, ending with praise: “Superior to a PRINCE – A GREAT MAN here has fallen.”[22]

[1] The author thanks former Governor James Douglas and Vermont historian Kevin Graffagnino for noting the prosecutions brought by state prosecutors against governors Horace F. Graham (1920) and Charles M. Smith (1937). While similar to Chittenden’s case because of their shared position, neither of them involved offenses determined to have been committed during their terms as governor. Only Chittenden bears that distinction.

[2] Wine Account, Johnson Family Papers, Doc 574, Vermont Historical Society.

[3] United States vs. Thomas Chittenden, RG 21.48.1, Vermont U.S. District Court, 1792-1797, Box 1, National Archives and Records Administration, Waltham, MA., passim.

[4] Saint Ansgar, Franciscan Media, www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-ansgar/.

[5] Vermont Gazette (Bennington), February 28, 1791.

[6] Ibid., May 10, 1793.

[7] Vermont Journal (Windsor), July 29, 1789.

[8] Ibid., February 29, 1796.

[9] U.S. v. James Fitch; Martin Van Dusen; David Callendar; Jacob Green; Philerus Brush; Joseph Poor, RG 21.48.1, Box 1, National Archives, Boston.

[10] An Act laying duties on licenses for selling Wines and foreign distilled spiritous liquors by retail; An Act making further provision for securing and collecting Duties on foreign and domestic Spirits, Stills, Wines and Teas, eff. June 5, 1794, Public Statutes at Large, vol. 1, chaps. XLVIII; XLIX (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown), 376-381.

[11] Vermont Journal, February 15, 1796.

[12] Hamilton Child, Gazetteer and Business Directory of Chittenden County for 1882-1883 (Syracuse: Hamilton Child, 1882), 256.

[13] American State Papers. Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, Commencing March 3, 1789, and ending March 3, 1815, vol. 5, (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832), 396.

[14] Gary G. Shattuck, Green Mountain Opium Eaters: A History of Early Addiction in Vermont (Charleston, SC, The History Press, 2017), passim; Return of the Whole Number of Persons Within the Several Districts of the United States, 1800, Vermont Historical Society, vermonthistory.org/client_media/files/Learn/Census%20Records/1800-Census.pdf .

[15] Innkeepers Licenses, 1791-1849, A123-00001, Vermont State Archives and Records Administration.

[16] Gary G. Shattuck, Insurrection, Corruption and Murder in Early Vermont: Life on the Wild Northern Frontier (Charleston, SC, The History Press, 2014), passim.

[17] Elections Division, Vermont Secretary of State, electionarchive.vermont.gov/elections/view/83330/.

[18] Thomas Chittenden to Paul Brigham, February 13, 1797, Paul Brigham Papers, mss-940, Silver Special Collections, University of Vermont. Thanks, again, to Kevin Graffagnino for referring the author to this resource.

[19] Vermont Journal, August 4, 1797.

[20] Ibid., September 22, 1797.

[21] Chittenden to Brigham, February 13, 1797.

[22] Vermont Journal, September 22, 1797.

2 Comments

Gary, impressive research! Given the hotly contested political divide, I suspect that Chittenden’s prosecution was partially motivated by political opponents. On the other hand, I’m not surprised that the modest fine in relationship to Chrittenden’s 41,000-pound estate received little attention. Maybe Vermonters viewed it like a speeding ticket and just a slap on the wrist. It’s a great article and an enjoyable read!

Thanks, Gene. I agree that politics may have had a role, but suspect that fears of having to ward off a Whiskey Rebellion II taking place in the removed, northern wilds also drove the decision to charge Chittenden. The Federalists constituted a new kind of legal creature still trying to find its legs, so they moved cautiously in exercising their authority; thus the year delay between the his offense and the decision to charge him. Chittenden was, by most accounts, someone who tried to get along with everyone, so I doubt his misstep actually angered the Federalists. Instead, he served as a convenient example to others not to mess with the new federal government.

The $50 fine was the statutory fine for his offense. Failing payment, the marshal would either seize a comparable amount of goods or file a lien on the property. Chittenden’s death removed either option. Regardless, none of this has ever been made public, until now.