By an accident of birth Thomas Jefferson (1742-1826) entered Virginia planter society and politics in 1769 when he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. By an application of his fortuitous talents, he became a political philosopher when America most needed one. Jefferson’s A Summary View of the Rights of British America (July 1774, two years before the Declaration of Independence) became the literary formulation upon which the founders went to war. Not the “ink war” that the colonies experienced through a sea of argumentative pamphlets in the decade prior to the Summary View, but actual life and death war.

In 1774, Jefferson seemed an unlikely candidate for drafting a writing upon which to launch a war. Indeed, his Summary View, much like John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, never advocated violent revolt. Rather, like Dickinson, Jefferson’s Summary View sought to present the American debate with Britain from the perspective of history.

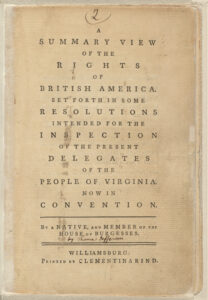

The Summary View (not a title given to the work by Jefferson) was originally written as a series of talking points for his fellow Virginians attending the First Continental Congress. The leader of the Virginia delegation, Peyton Randolph, took it upon himself with his fellow Virginia delegates to get Jefferson’s notes published under the title Summary View. It was printed as a pamphlet in September 1774 by Clementina Rind in Williamsburg shortly before her death. Jefferson, having been taken ill prior to the start of the congress in Philadelphia, ensured copies of his essay reached Randolph.

As Jefferson recollected, he saw his essay as a work of a free man who had his freedom naturally, not by the gift of a sovereign. Political freedom was the natural birthright of all men (with exceptions as we know—African Americans, women, Indigenous peoples) and the colonists, as free born Englishmen, only sought to re-establish those rights which they felt had been taken from them by the king, Parliament, or both.

The thesis of the Summary View echoed an earlier obscure essay by Richard Bland (Rights of the British Colonies, 1766) which Jefferson likely read as a student and during the time his Enlightenment natural rights theories began to develop. Bland argued that the colonies were part of the king’s dominions, but not subject to the political control of Parliament. This was a radical departure from most contemporary writings. John Dickinson never made such a pronouncement in his Letters from 1767-1768.

Jefferson was not subtle. He sought a new concept inspired by Enlightenment thought for the relationship between the colonies and Britain; “Jefferson, together with the Adamses in Massachusetts and James Wilson in Pennsylvania, set forth the new theory of the imperial connection in which the colonies were equal self-governing states owing allegiance to the King.”[1] Jefferson’s approach to the debate with Britain compared to Dickinson’s is on one level a matter of temperament; Dickinson was a decade older than Jefferson. Also, Dickinson spent several years in England studying law whereas Jefferson was American trained. There was also the matter of the seven years difference in the dates of their writings. Dickinson wrote before two defining events in early 1770s Boston—the Boston Massacre, and the Tea Party and the British response. A lot had changed in seven years as Americans became ever more emboldened.

Jefferson’s Summary (which was edited for print by his Virginia delegation colleagues) began with a quote from his favorite Roman writer, Cicero (whether Jefferson or Peyton Randolph chose this Cicero quote is not known). Jefferson aimed the quote directly at King George III rather than parliament,

it is the indispensable duty of the supreme magistrate to consider himself as acting for the whole community, and obliged to support its dignity, and assign to the people, with justice, their various rights, as he would be faithful to the great trust reposed in him.[2]

Jefferson clearly identified Cicero’s supreme magistrate with George III. The order of government in the British system existed with the monarch as the locus of governmental power and authority, unlike what Jefferson foresaw for the colonies where he envisioned the people (by the eighteenth century definition), not those ordained by heaven, as the supreme magistrates. This would come to pass in the first line of the Constitution as “We the People.” Jefferson was convinced that George III would come to realize “that his is no more than the chief officer of the people, appointed by the laws, and circumscribed with definite powers, to assist in working the great machinery of government.”[3] Jefferson was describing what would eventually become the model for the American president through the Constitution.

Attributing these parameters to the eighteenth century English monarch was ludicrous. While the monarchy no longer espoused the divine rights doctrine, it certainly was not seen as a creation of the people through the people’s law. While Jefferson’s thinking was pure Enlightenment understanding relative to political liberty, the British monarchy was far from that understanding.

Jefferson’s manuscript for the Virginia delegates began as follows:

Resolved that it be an instruction to the said deputies when assembled in General Congress with the deputies from the other states of British America to propose to the said Congress that an humble and dutiful address be presented to his majesty begging leave to lay before him as chief magistrate of the British empire the united complaints of his majesty’s subjects in America; complaints which are excited by many unwarrantable incroachments and usurpations, attempted to be made by the legislature of one part of the empire, upon those rights which god and the laws have given equally and independently to all.[4]

A central argument of Jefferson’s Summary was that the colonists “carried with them not just the laws but the rights that they possessed before they emigrated.”[5] The Summary would summarize those rights and find their roots in Anglo-Saxon England. It was in Anglo-Saxon England, prior to the arrival of the Normans, that Jefferson, much like John Dickinson in his Letters, found the earliest parallels to the natural rights theory of political association animating the colonial movement. Jefferson wrote,

our ancestors, before their emigration to America, were free inhabitants of the British dominions and Europe, and possessed a right which nature has given to all men, of departing from the country in which chance, not choice, has placed them, of going in quest of new habitations, and of their establishing new societies, under such laws and regulations as to them shall seem most likely to promote public happiness.[6]

Jefferson would equate the Saxons from the wilds of northern Germany with the early seventeenth century English emigrants. In an outlandish analogy, Jefferson wrote “And it is thought that no circumstance has occurred to distinguish materially the British from the Saxon emigration.”[7] He was clearly using some slippery history in an attempt to make a point.

He further found arguments for British control of trade to be misleading. While some founders thought Britain had every right to regulate trade, Jefferson thought it rather a further example of tyranny. Jefferson went so far as to cite a 1651 treaty by Oliver Cromwell that gave the colony of Virginia “free trade with all peoples and nations,” only to have that trade freedom revoked by Charles II with a reversion to the trade policies of Charles I which favored England exclusively.[8] This was not something lightly inserted by Jefferson. Many colonists looked to the English Glorious Revolution of 1688 as the English people themselves overcoming the tyranny of the restored Stuart monarchy. Charles II was simply another “divine rights” monarch—and a Catholic—and like his younger brother James II (who would be deposed in 1688 and replaced with his Anglican sister Mary and her husband William). Monarchy, in the developing Enlightenment nomenclature, was tyranny against the natural rights of men (white males usually born of privilege at this point), and religious monarchy infused with divine rights theories were the worst.

A manufacturing law that was particularly troublesome for American industry required American raw materials to be shipped to Britain for processing and then reshipped to the colonies for sale. An example from the reign of George II involved beaver pelts. The pelts, while obtained in America, could not, legally, be crafted into a hat or article of clothing in the colonies. Rather, the pelts had to be shipped to England for processing into apparel and reshipped to America for sale. Jefferson saw this as “an instance of despotism to which no parallel can be produced in the most arbitrary ages of British history.”[9]

Much like he would do in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson relied on a series of rapid-fire indictments against George III in the Summary View. After attempting to draw an analogy between English colonists of the seventeenth century and Saxon colonists or emigrants of the seventh century he sought to give the British the benefit of the doubt by writing,

Single acts of tyranny may be ascribed to the accidental opinion of the day; but a series of oppressions, begun at a distinguished period, and pursued unalterably through every change of ministers, too plainly prove a deliberate and systematic a plan of reducing us to slavery

The reference to slavery comes across as patently absurd.[10] Although to the political and legal argument (the English common law did not recognize enslavement, as Jefferson clearly knew) Jefferson was making the case that he, and other founders, saw themselves as slaves to the British colonial system without due representation. Hence, with a straight face, the founders could claim tyranny and slavery as the negative outcome of continued interaction with Britain.

Jefferson saw malicious tyranny put upon America from Britain everywhere he looked, and the Summary View reflects this. The Summary View was the Declaration of Independence in preview. Many of the indictments against George III in the Declaration first appeared in the Summary View. One involved law and its administration. Those colonists charged with serious crime were required to journey to England at their own expense, defend themselves, and, if acquitted, return to the colony of their origin. At this point in the Summary, Jefferson reached out to the king to ask for his help:

That these are the acts of power, assumed by a body of men, foreign to our constitutions, and unacknowledged by our laws, against which we do, on behalf of the inhabitants of British America, enter this our solemn and determined protest; and we do earnestly entreat his majesty, as yet the only mediatory power between the several states of the British empire, to recommend to his parliament of Great Britain the total revocation of these acts, which, however nugatory they be, may yet prove the cause of further discontents and jealousies among us.[11]

Jefferson’s rage towards George III became more focused as he proceeded.

King George was made out to be an unnerved monarch, someone surprised and unsettled by the turn of events in America. A monarch who saw himself as unfit or somehow deficient for the role he found himself in . . . Jefferson saw George as someone too easily misled by Parliament, someone who would not advocate for the interests of the colonies, and someone who was overwhelmed by the agility of his members of Parliament.[12]

Similar to the Declaration, Jefferson blamed George III for the slave trade, not necessarily enslavement as it existed. Jefferson and the founders in general drew a distinction between the slave trade and enslavement.

In one of Jefferson’s final arguments in the Summary View, he again looked to the Anglo-Saxon period for a comparison of land ownership with which to contrast colonial America. Jefferson idealized the supposed Saxon concept of land ownership whereby land was held by an individual by natural right and asserted that the American colonists were the lineal descendants of this Saxon practice. The British government, according to Jefferson, were following the land use patterns developed after the Norman conquest of 1066. In Jefferson’s telling, William, after his conquest of England, subsumed all land under the monarchy, doling it out to his supporters. As “America was not conquered by William the Norman, nor its lands surrendered to him, or any of his successors,” the British crown has no claim to American territory.[13] This theme was originally used by Jefferson several months earlier in the Resolutions of Freeholders of Albemarle County in Virginia. Writing on July 26, 1774, Jefferson again summarized the resolves of the county leaders:

That the inhabitants of the Several States of British America are subject to the laws which they adopted at their first settlement, and to such others as have been since made by their respective Legislatures, duly constituted and appointed with their own consent. That no other Legislature whatever can rightly exercise authority over them; and that these privileges they hold as the common rights of mankind, confirmed by the political constitutions they have respectively assume, and also by several charters of compact from the Crown.[14]

Furthermore, Jefferson held the early charters designating colonies as Crown Colonies to be fraudulent. This whole argument was not repeated in the Declaration, for good reason—it was not a sound argument except in the fertile mind of Jefferson. The Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone wrote that the Summary View was “more noteworthy for boldness and fervor than for historical precision or literary grace.”[15] Nonetheless, Jefferson’s insistence on law drafted and framed by men, not gods, and the reliance on “the common rights of mankind” was classic Enlightenment thought being reflected in the developing founding language.

Concurrently, in the busy summer of 1774, Jefferson drafted a Declaration of Rights for the Virginia Convention which was scheduled for August 1774. This Declaration was based on the Resolutions of the same time. While the Resolutions “resolved,” the Declaration “declared” and enumerated the rights Jefferson saw as emanating from the natural rights doctrine swirling through the Enlightenment world. His was an Enlightenment captured for an American purpose.

Jefferson compared George III with his grandfather George II. According to Jefferson, George II followed the law in obtaining parliamentary approval when he sent troops to America during the French and Indian War., whereas George III sent troops (including German Hanoverians) to America without seeking Parliament’s approval. Jefferson argued on one hand that George III did not follow British law, while on the other hand arguing British law had no effect in the colonies. In essence, Jefferson saw no future for America as a British colony. In Jefferson’s most radical mind, the colonies by 1774 should have declared independence.

Keep in mind that the original intent of what became published as a Summary View was intended to be a series of notes and talking points for members of the Virginia delegation (fashioned after the Albemarle County Resolves) to the First Continental Congress. Jefferson was pushing his colleagues towards independence, where he was already mentally. Jefferson’s radical outlook was similar to, but not identical to, other more voluble and violent practitioners of revolution such as Samuel Adams or Patrick Henry.

With the release of the Summary View Jefferson was irrevocably tied to the American independence movement. Never again would the solitude he craved from the Monticello mountain top be his to enjoy. The struggle for political independence and natural liberty, inspired by Enlightenment ideals, became by his death in 1826 something utterly unrecognizable to Jefferson. The forces he championed and unleashed were beyond control; many started to take the Enlightenment ideals literally. The revolutionary movement he marshalled with language in the 1770s became truly revolutionary in practice as the years passed. Natural liberty and other terms moved well beyond the Anglo-Saxon past that Jefferson idealized, however specious his argument was. The Summary View, planned or not as such, became America’s first organized approach to the Enlightenment.

[1] Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (Norwalk: The Easton Press, 1987), 73.

[2] Carl Richard, The Founders and the Classics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), 37.

[3] Thomas Jefferson, A Summary View of the Rights of British America Reprint (Norwalk: Easton Press), 5.

[4] The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition, ed. James P. McClure and J. Jefferson Looney, Main Series, Volume 1 (1760–1776), rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/TSJN-01-01-02-0090.

[5] Jude M. Pfister, Defining America in the Radical 1760s, John Dickinson, George III and the Fate of Empire (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers), 192.

[6] Jefferson, Summary View, 6.

[7] Ibid., 6.

[8] Pfister, Defining America, 195.

[9] Jefferson, Summary View, 10.

[10] Ibid., 11.

[11] Ibid., 16.

[12] Pfister, Defining America, 197.

[13] Jefferson, Summary View, 20.

[14] Henry Steele Commager, and Richard B. Morris, eds., The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six, The Story of the American Revolution as told by Participants Volume 1 (New York: The Bobb-Merrill Company, Inc.), 22.

[15] Dumas Malone, Jefferson the Virginian (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1948), 182.

Recent Articles

The American Princeps Civitatis: Precedent and Protocol in the Washingtonian Republic

Thomas Nelson of Yorktown, Virginia

The Course of Human Events

Recent Comments

"General Israel Putnam: Reputation..."

Gene, see John Bell’s exhaustive Analysis, “Who Said ‘Don’t Fire Till You...

"The Deadliest Seconds of..."

Ed, yes Matlack's son was reportedly a midshipman on the Randolph. That...

"The Whale-boat Men of..."

From my research the British Navy kept a very regular schedule across...