In April 1775, Isaac Bissell was a crucial link between the Patriots of Massachusetts and the government of neighboring Connecticut. His actions contributed to alerting many communities along the Atlantic coast about the outbreak of war in Lexington. Nevertheless, through a chain of circumstances, Isaac Bissell’s name has been overwritten in history books.[1]

This story starts in February 1775, when two gentlemen from Connecticut visited the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, then meeting in Cambridge. The Bay Colony’s rebel legislature had convened on and off since the preceding October, defying Parliament’s Massachusetts Government Act and preparing for war against the royal governor if necessary. That congress wanted allies, so its leaders were pleased to hear from William Williams and Nathaniel Wales, Jr.

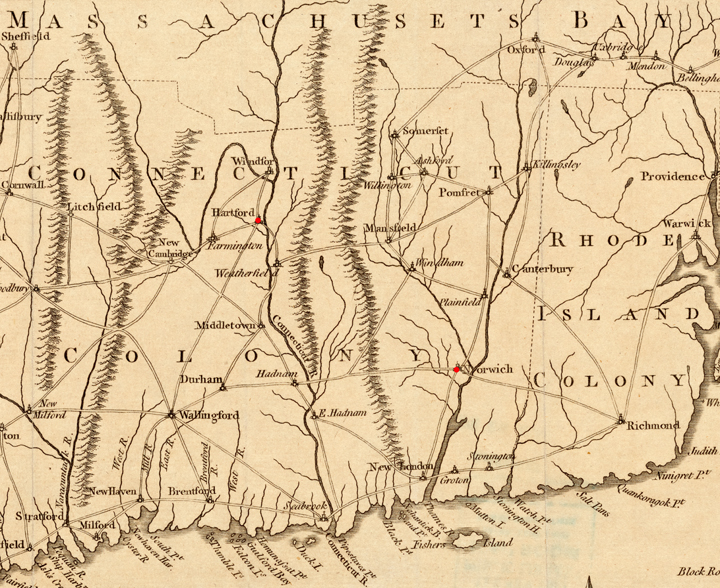

Williams was the speaker of the Connecticut assembly, a militia colonel, and a son-in-law of his colony’s elected governor, Jonathan Trumbull. Wales was a representative from the town of Windham. Both men lived in eastern Connecticut, closer to Cambridge than many of their colleagues. Back in May 1773, the Connecticut legislature had named Williams and Wales to its “standing Committee of Correspondence and Enquiry” with a mandate to “maintain a correspondence and communication with our sister Colonies” and “obtain all such intelligence” about the political conflict with the Crown.[2]

The official record of the Connecticut assembly says nothing about that body sending Williams and Wales to speak to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in early 1775. The colonial legislature might have preferred a low profile for this potentially treasonous outreach. Arguably the two men were already empowered to consult with colleagues in Massachusetts because of their seats on the standing committee of correspondence.

Williams and Wales’s visit shows up only in Massachusetts records. On February 15, the provincial congress named committees to converse with the two men—one to greet them, then a second to sit down with them in Ebenezer Stedman’s tavern for a serious conversation. The official description of those discussions was spare and bland, but their importance was clear. Both committees included such high-ranking leaders as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Thomas Cushing (usually speaker of the Massachusetts house); members of the busy committee of safety and supplies; and top militia officers. Furthermore, though the congress was preparing to adjourn, it ordered that no members head home “until the conference with the committee from Connecticut is over.”[3]

The day after the discussion at Stedman’s, the Massachusetts congress named a committee of nine leading members (their mandate defined by yet another committee) “to correspond with the House of Assembly of Connecticut; and, if necessary, with the other neighboring colonies.” That resolution made clear the mood of the assembly:

While the iron hand of power is stretched out against these American colonies, and the abettors of tyranny and oppression are practising every art to sow the seeds of jealousy and discord among the several parts of this country, it is incumbent on us to take every step in our power to counteract them in their wicked designs; and . . . we are convinced, that the union now established throughout the several colonies can never be maintained without frequent communication of sentiments between them[4]

In addition, as the Massachusetts congress prepared to recess, it authorized this committee to maintain ties with neighboring colonies during adjournments. Among the nine men given that authority was Joseph Palmer (1716–1788), a militia colonel from Braintree and member of the committee of safety and supplies. Williams and Wales went home to report to their colleagues.

On April 8, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress moved closer to war. The body voted “to make preparations for their security and defence by raising and establishing an Army.” It decided to appoint “delegates . . . to repair to Connecticut, to Rhode Island and New Hampshire.” Those delegates were to ask the neighboring colonies about “furnishing their respective quotas for general defence,” or a combined army.[5]

The Massachusetts congress then chose members as its delegates. The contingent for Connecticut consisted of militia colonel Jedediah Foster of Brookfield and John Bliss of Wilbraham, soon joined by Timothy Danielson of Brimfield.[6] All three men came from towns in central Massachusetts close to the Connecticut border, making a journey to Hartford less onerous. Danielson, furthermore, had spent years in the neighboring colony as a Yale College student.[7] Foster later reported that Danielson “Immediately proceeded from Concord to Governour Trumbul with the papers as Directed by the Congress.” However, “from the then Appearance of affairs,” the Connecticut governor “did not think proper to Call the Assembly” to authorize raising troops.[8] Trumbull had already convened one special legislative session in early March and publicly proclaimed there was no need for another, so he would need a strong reason to reverse himself.[9]

On April 15, the Massachusetts congress adjourned, planning to gather again on May 10 in Concord. Already the conflict with the Crown was heating up. The previous day, HMS Nautilus arrived in Boston, bringing instructions from the London government for the royal governor, Gen. Thomas Gage. Britain’s secretary of state for the colonies, Lord Dartmouth, had advised that it was time for Gage to “arrest the principal actors and abettors in the Provincial Congress.” Patriot leaders were leaving Boston, apparently having received warnings of the imperial government’s policy from a previous ship.[10]

On April 19, Joseph Palmer was staying with his son’s in-laws in Watertown, about nine miles outside of Boston. As a member of the committee of safety, he knew there was an arms cache in Concord. Early that morning, Palmer started to receive reports that a British army column was moving west through Cambridge. Then came news from Lexington, further out. Palmer dashed off this message at “abt 8 o’clock”:

To all whom it may concern, be it known, that the Regular Troops have this morning kill’d six men near Lexington Meeting House; this news is brot: to Watertown by Mr. Sanger, who told me that he saw the men lie dead.

J. Palmer

of the Congress Com:tee[11]

Two hours later, Palmer wrote out a more detailed dispatch to go to Hartford. He handed it to Isaac Bissell, a twenty-six-year-old blacksmith from Suffield, a town on Connecticut’s northern border. It is unclear whether the Massachusetts Patriots had already hired Bissell as a dispatch rider or he happened to be in Watertown that day. Either way, Palmer made Bissell a courier to “Col. Foster of Brookfield, one of the Delegates” from Massachusetts to Connecticut. But the committee man did not seek to keep that letter confidential. Instead, Palmer addressed all supporters, and he probably encouraged Bissell to spread the news everywhere he went.

Palmer’s letter said:

Watertown / Wednesday Morning 10 Clock

To all the Friends of american liberty be it known that this morning before break of Day a Brigade consisting of about 1000 or 1200 men Landed at Phips’ Farm in Cambridge and marched to Lexington where they found a Company of our Colony Militia in arms; upon whom they Fired without any Provocation & killed six & wounded four Others[.] by an express this moment from Boston we find another Brigade are now on their March from Boston supposed to be about 1000[.] The Bearer Mr. Isaac Bissell [is] charged to alarm the country quite to Connecticutt and all Persons are Desired to furnish him with such Horses as they may be needed

I have spoke with severall Persons who have seen the Dead & wounded[.] Pray Lett the Delegates from this Colony to Connecticutt see this

they know

J. Palmer

one of the Com. of Safety

Colo. Foster is one of the Delegates[12]

Palmer’s primary goal was to help Foster and the other Massachusetts delegates to Connecticut convince that colony’s government to raise troops. As a secondary purpose, he also wanted to rouse “all the Friends of American liberty” who might see this message along the way. But Palmer faced a challenge in raising that alarm. Back in September 1774, dire rumors of a British military attack in Boston had spread through rural Massachusetts and Connecticut, prompting thousands of militiamen to mobilize—only to learn that there had been no attack, no deaths, not even any injuries. Earlier that spring, contingents of British soldiers had marched out of Boston several times with no consequences. How could Palmer convince people that this time the redcoats really had killed people? When Palmer wrote, “Lett the Delegates from this Colony to Connecticutt see this / They know” me, he was trying to establish his credibility.

Isaac Bissell rode west with Palmer’s letter, his route taking him safely south of the Concord road. In early afternoon he reached Worcester, another center of political resistance where the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was storing weapons. Local organizers probably gave him a fresh horse and a meal. During that stop, Worcester’s new town clerk, Nathan Baldwin, quickly copied the letter Bissell was carrying.[13] To avoid unnecessary delay, Baldwin probably did not take extra time to check if he had exactly matched the original letter’s spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and other small details; eighteenth century writers did not demand as much consistency in those matters as we do today. At the bottom Baldwin added a line authenticating his new page as reliable information, something like:

A true copy taken from the original per order of the Committee of Correspondence for Worcester

Attested Nathan Baldwin, Town Clerk

Worcester April ye 19th 1775.[14]

The Worcester committee probably saved one copy of the dispatch for themselves, and they definitely sent a copy south with another rider.

Bissell continued west to Springfield, where another “true Coppy” of his message was made for that town’s selectmen. On that copy the rider’s name could be read as “Isaac Russell.”[15] By April 20, Springfield militiamen were marching east to Boston, eventually to serve in a regiment under congress delegate Timothy Danielson.

Isaac Bissell fulfilled his assignment to ride to Connecticut on the morning of Thursday, April 20. Early that day, Massachusetts delegates Jedediah Foster and Timothy Danielson learned about the outbreak of war and began telling politicians in Hartford. In Wethersfield, a few miles to the south, Silas Deane started a journal:

Memo. / Thursday 20th April 1775 Mr. Isaac Sheldon of Hartford came over from Hartford half past Ten in ye. Morning with a Letter from J. Palmer informing that the Regular Troops fired, early the Morning before on a Number of people at Lexington and killed Six of them, that they then Continued their March for Concord, and that they had intelligence of another large Body of them on their march toward Concord on another Road—

Palmer’s worry that people might doubt him turned out to be well founded. Deane went on: “The News was discredited, from the suddeness of its arrival, & other Causes.” The very fact that Bissell had brought this letter so quickly, far ahead of any confirmation—its “suddeness”—ended up working against it. Deane went up to Hartford and met with other politicians, but they “Conferrd on the Intellgence Wh. was discredited.”[16] The only action those men took was to send another express rider south to Middletown with the possible news.

In contrast, Massachusetts delegates Foster and Danielson had no doubts. They knew Palmer and trusted his report. Early on April 20 those two men “set out for Lebanon,” home town of Gov. Jonathan Trumbull. They ran into the governor and other Connecticut politicians in the town of Norwich. He had already “Received the Tragical Narrative from Colo. Palmer,” he told them, and now “Chearfuly Consented to Call the assembly of the Colony” the next week to raise an army.[17]

The next day, Williams, Wales, and the governor’s son Joseph Trumbull wrote to John Hancock as president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress:

Writs are gone out to Call the Genll. Assembly to meet at Hartford next Wensday—Every preparation is making to Support your Province—We have many Reports of what is doing with you, the particulars, we cannot yet get with precision—the Ardour of Our People is such that they can’t be kept back;—The Colonels are to forward part of the best men & most Ready, as fast as possible; the remainder to be ready at a Moments warning—these are the present movements with us.

In the same letter, those Connecticut men pleaded for more information: “our Accots. are so various We know not what to rely on,” they said. Yet another son of the governor, David Trumbull, was sent to find Hancock and gather all the information he could. Reflecting the importance of information in this conflict, Williams, Wales, and Trumbull advised Hancock and his colleagues to distribute the “most Authentic Accots. of the late Transactions, to forestall, such exaggerated Accots. as may go from the Army & Navy.”[18]

By the time the Connecticut assembly met in formal session the next week, some of the colony’s militia regiments were already helping to besiege Boston or on their way. Among those men was Isaac Bissell, a private in Capt. Elihu Kent’s company from Suffield. At the start of 1776, Bissell signed up as a sergeant in Capt. John Harmon’s company, Col. Erastus Wolcott’s regiment. Bissell served through March 1776 and the British evacuation of Boston.[19]

On July 7, 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress’s committee of safety “Passed upon Mr. Isaac Bissel, a post rider’s account, amounting, as by copy on file, for two pounds one shilling; and a certificate was given him for the committee on accounts.”[20] Bissell took this paper to the man he understood was the congress’s treasurer, who answered that “he Could not alow it unless atested by the Provenchal Congress.”[21] On July 10, the full provincial congress assigned three men to “consider the account of Mr. Isaac Bissell.”[22] But that committee never finished the task before the congress dissolved in favor of a newly elected Massachusetts General Court, the official legislature. When Bissell asked about his money, congress members told him “they Could not doe any more bisness and it must be Put of till the assembly Sat and they took my order and Put it into the files.”

Eight months later, the British military had pulled out of Boston, and Bissell’s bill was still unpaid. In March 20, 1776, the rider wrote to his original contact, Joseph Palmer, now a member of the legislature’s upper house: “Sir you may Remember when Lexinton Fite was you gave me an Express to Cary to hartford in Connecticut which I did.” He recounted his attempts to get paid the previous July and concluded: “now Sir I Cant Neither get my order nor the money for I Cant Lite on any Body that Noes any thing abought it . . . and I think I Earn my money.”[23] Within two days, Palmer passed on Bissell’s request to the lower house.[24] On April 4, the Massachusetts House took up Palmer’s petition on behalf of Bissell, assigning it to a one-man committee. Four days later, that became a three-man committee. On April 23, 1776, slightly over a year after Isaac Bissell completed his ride to Hartford, the Massachusetts General Court finally voted to pay him the £2.1s. he had asked for.[25]

Isaac Bissell married Amelia Leavitt, niece of his first company captain, on July 4, 1776. They had thirteen children between 1777 and 1801.[26] In July 1779, the British army attacked New Haven, and Bissell marched again as part of a militia alarm. In peaceful times, he operated a blacksmith shop in Suffield, though that apparently did not always support the family well. In October 1778 he advertised “SIXTEEN HUNDRED weight of BOHEA TEA” for sale, “as I am in necessity for a sum of money in a short time.” In March 1781 Bissell offered to sell his twelve-acre farm north of town “For Hard, Continental, or State’s Money,” and he finally made that sale in 1788.[27] For a time, the Bissells moved to Hanover, New Hampshire, where Amelia died, but Isaac came back to Suffield. He died in 1822 and was buried in the town cemetery.

America does not remember Isaac Bissell’s service as a courier. Instead, there have been articles, artwork, poems, and even a picture book celebrating Israel Bissell for carrying Joseph Palmer’s message.[28] Indeed, many authors have credited “Israel Bissell” with riding all the way to New York, or to Philadelphia, or beyond.

As described above, in Worcester the town clerk, Nathan Baldwin, made a copy of Palmer’s letter on the afternoon of April 19 and sent it south. As Isaac Bissell continued riding west, a second, unknown rider carried Baldwin’s copy down to Brooklyn, Connecticut, arriving by eleven o’clock in the morning on Thursday, April 20. Daniel Tyler, Jr., then made another “true Copy” before he and his father-in-law, militia colonel Israel Putnam, set out toward Boston. By four o’clock that afternoon, that text had reached the town of Norwich.[29] That was the message that alerted Governor Trumbull and convinced him to summon the Connecticut legislature.[30] Ironically, Tyler’s copy of Baldwin’s copy of Palmer’s letter turned out to be more galvanizing than the original sent to Hartford. Trumbull’s response showed the value of spreading multiple copies of the dispatch.

That transcription which reached Norwich contained some errors—understandable given how two people had hastily copied a document in unfamiliar handwriting. The Tyler text named the first rider as “Israel Bissell” and rendered the Worcester clerk as “Nathan Balding.”[31] Naturally, those errors persisted when people used that document to make further copies. Tyler’s rendering was printed in that day’s Norwich Packet newspaper, widening the reach of the message.[32] Two days later, the same printers used that text again, alongside two later accounts of the battle, in a handbill headlined “Interesting Intelligence.”[33]

The transcribed message continued south. Norwich mill owner Christopher Leffingwell copied it, signed off that his copy was as accurate as he could make it, and sent it on to New London. Leffingwell’s paper arrived in that port at seven in the evening on April 20, and a committee of four men sent another copy on along the coast. But the text of the warning now named the original rider as “Trail Bissell.”[34] That message arrived in Lyme after midnight and by noon had gone through the towns of Saybrook, Killingsworth, East Guilford, Guilford, and Bradford on its way to New Haven.[35]

The April 24 New-York Gazette reported: “Yesterday Morning we had Reports in this City from Rhode-Island and New-London, That an Action had happened between the King’s Troops and the Inhabitants of Boston.” People did not believe that news, probably remembering the false alarm back in September 1774. Then in the early afternoon an express rider trotted in from Fairfield, Connecticut, with an attested copy of Palmer’s message. A committee of five men in Fairfield had combined that original dispatch with an April 20 letter from Ebenezer Williams of Pomfret to Obadiah Johnson of Canterbury, passing on more detailed (though not necessarily more accurate) news of the previous day’s fighting.[36]

When Hugh Gaine printed all that text in the New-York Gazette and as a handbill, he named the original rider as “Israel Bessel” and the man who wrote the letter as “T. Palmer.”[37] But even without exact transmission, the multiple signatures on the papers had the intended effect: they convinced New York Patriots that the news was authentic. In a 1940 article for the American Antiquarian Society, John H. Scheide described a copy of the New York handbill with a note on the back in the handwriting of Patriot organizer Alexander McDougall. He recorded that the news arrived in New York City at about two o’clock on Sunday, April 23, and by four o’clock the city’s committee of correspondence decided to forward “the intelligence by Mr. Moorbach express to the Southard.”[38]

Moorbach set off “express to New Brunswick [New Jersey] with directions to stop at Elizabethtown and acquaint the committee there.” The New Brunswick committee in turn were “requested to forward this to Philadelphia.”[39] In Elizabethtown, Elias Boudinot recorded the path of the message that reached him, from Worcester through Fairfield.[40] Overnight the news went through New Brunswick, Princeton, and Trenton, and in each town at least two committee members signed off on a copy for the next stop. At five o’clock in the afternoon on April 24, five and a half days after the fighting had started, a copy of Joseph Palmer’s dispatch and Ebenezer Williams’s letter reached Philadelphia, the largest city in North America. Thirty-eight different men had signed off on copies.[41]

Those documents (without all the signatures) were published in a special two-page supplement to the April 24 Pennsylvania Packet; it called the first rider “Trail Bissel.” The next day, the same text ran in the Pennsylvania Evening Post, naming “Train Bissel.” By this time, Jedediah Foster was “Col. Forster,” and his home town of Brookfield was dropped. The Packet’s version was also translated into German and printed in the April 25 Wochentliche Philadelphische Staatsbote newspaper. William and Thomas Bradford issued their version of the dispatch naming “Israel Bissell” in the April 26 Pennsylvania Journal, with a handbill following.

From Philadelphia, messengers carried the report to New Castle, Dover, and New Christiana, Delaware, then Head of Elk, Maryland. At Baltimore, the news arrived in time for Mary Katharine Goddard to print the Palmer and Williams letters in the April 26 Maryland Journal and as another handbill.[42] This text named the first rider “Tryal Russell,” and the Worcester clerk “Nathan Balding,” but it also restored the phrase “Col. Foster, of Brookfield.” Evidently by this time multiple copies of the dispatch had made their way south through branching paths.

Patriots in Baltimore sped copies to their delegates at the Maryland Provincial Congress meeting in Annapolis because “they should have notice before they adjourn.” Four militia officers added a promise of “our Immediate and chearful assistance in the Seizing of the Arms & Ammunition at Annapolis.” They also apologized for at first sending the delegates a “Coppy” rather than “the original Intillegence,” reflecting continued concern about making sure each message looked as authentic as possible. Of course, what those men called the “original Intillegence” was also a copy, simply an earlier one.[43]

In Williamsburg, Virginia, John Pinkney reprinted the Palmer and Williams letters from an April 24 Philadelphia newspaper in a supplement to his Virginia Gazette issued on the evening of Friday, April 28. The next day, Pinkney’s rivals John Dixon and William Hunter announced in a supplement to their own Virginia Gazette that “This morning arrived an express from the Northward,” sharing the report from Philadelphia. Both these newspapers called the rider “Trail Brissel.” Another handbill followed.

Riders and newspapers continued to carry Palmer’s message south. The alert reached Halifax, North Carolina, on May 8, and four days later the North-Carolina Gazette in New Bern reprinted the Philadelphia article. This time the first rider was “Trial Brisset.” By then other reports of the battle in Massachusetts were coming by sea. The committee-man’s early alert, now carried by a dozen or more men in turn, had become anticlimactic.[44]

Eventually the American newspaper reports were reprinted in London. John Almon’s Remembrancer, a round-up of news for the year, included a version “From a New-York paper April 24” that named “Israel Bessell” and “T. Palmer.”[45]

In 1861, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, one of America’s most popular writers, composed “Paul Revere’s Ride.” That poem made the Boston silversmith into a household name, and it provoked widespread interest in details of the Lexington Alarm. For the first time families began to publicly discuss ancestors who had sent the signals from “the Old North Church,” as Longfellow called that building and it irrevocably became. Local historians sought to identify other riders carrying important Revolutionary news. Americans claimed that honor for their ancestors, not always credibly.

Given that interest, historians paid more attention to the copies of Joseph Palmer’s April 19 letter in archives and newspapers. Most of those transcriptions had been made along the eastern seaboard, not from the original sent to Hartford but from the “true copy” that Nathan Baldwin wrote out in Worcester and from other “true copies” made from that one. As those documents moved through Connecticut, the name of the first rider had mutated to “Israel Bissell.” Some of those versions were printed, producing more copies. As a result, many of the documents available to scholars carried that name. Even though the rider’s name continued to evolve into new forms like “Tryal Russell” as the message moved south, historians latched onto “Israel Bissell” as the true name of the rider. The multiple documents showing how Isaac Bissell had billed the Massachusetts government for his ride to Hartford remained unpublished in a state archive until Lion G. Miles began quoting them in 2004.

Furthermore, that chain of documents with the same basic text produced the misconception that one man rode all the way to New York or Philadelphia, switching horses along the way. This legend was embellished with details like the claim that his first mount collapsed and died as he rode into Worcester. At the time authors made that assumption, Americans were traveling long distances by railroad and had largely lost touch with the realities of travel in 1775. People more familiar with sending messages by horse would have known that couriers worked in relays, stopping for meals and sleep as well as fresh mounts. Spreading the alert from Watertown to Philadelphia in five days and seven hours took the work of many riders, and almost all of them were anonymous. The one exception was the New York reference to “Mr. Moorbach,” but that name was not published until 1940. In the early 1900s, all the credit went to “Israel Bissell.”

Researchers then found a man actually named Israel Bissell—a farmer from East Windsor, Connecticut, born in 1752.[46] He and his brother Justus joined Captain Wolcott’s Connecticut company in July 1776 and served for a month.[47] Later this Bissell family moved to a part of Middlefield, Massachusetts, that would become Hinsdale. Israel bought farmland, married Lucy Hancock in 1784, raised sheep, and fathered six children. He died in 1823 at age seventy-one, and was buried in Hinsdale under a stone that said nothing about Revolutionary War service.[48]

In the twentieth century, the ride of “Israel Bissell” was lauded in art, poetry, and song as a forgotten feat equal to or greater than Paul Revere’s ride. In 1967 the local Daughters of the American Revolution added a bronze plaque to the grave of that Hinsdale farmer. It reads, “In Memory of Israel Bissell post rider from Watertown to Philadelphia alerting towns of British attack at Lexington April 19, 1775.”[49] But all that celebration was just the result of a spelling error back on the frantic afternoon when the Revolutionary War began.

[1] This article draws from fine previous studies of how Joseph Palmer’s April 19 message moved down the Atlantic seaboard in 1775, including John J. Scheide, “The Lexington Alarm,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 50 (1940), 49–79; Elizabeth Merritt, “The Lexington Alarm, April 19, 1775: Messages Sent to the Southwaid [sic] After the Battle,” Maryland Historical Magazine, 41 (1946), 89–114; and Robert L. Berthelson, “An Alarm from Lexington,” Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, www.sarconnecticut.org/an-alarm-from-lexington/, and Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, massar.org/alarm-from-lexington/. Those articles did not have the benefit of Lion G. Miles’s work highlighting documents about Isaac Bissell in the Massachusetts State Archives. See Miles, “The True Story of Bissell’s Ride in 1775,” July 21, 2004, at www.iberkshires.com/story/15001/The-true-story-of-Bissell-s-Ride-in-1775.html; and Miles, “Letter: Superhuman ride of Bissell is fake news,” Berkshire Eagle, April 20, 2018, at www.berkshireeagle.com/archives/letter-superhuman-ride-of-bissell-is-fake-news/article_9d213ac1-c15d-5bc9-924a-cdea38674c26.html. Miles’s influence can be seen in David Robinson, “The Shot Eventually Heard ’Round the World,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, vol. 28, no. 3 (summer 2006), 60–5, but that author was still reluctant to move away from the then-standard credit to Israel Bissell. As of this writing, Wikipedia includes entries for both Isaac Bissell and Israel Bissell, the latter supposedly taking over in Worcester from a man with a nearly identical name. This article presents a more plausible scenario.

[2] Connecticut committee of correspondence: The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, Charles H. Hoadley, transcriber (Hartford: Case, Lockwood & Brainard, 1887), 14:156. Williams is well documented as a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

[3] Massachusetts committees: William Lincoln, editor, Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775 (Boston: Dutton & Wentworth, 1838), 105.

[4] “to correspond”: Lincoln, Journals of Each Provincial Congress, 106.

[5] “to make preparations”: Lincoln, Journals of Each Provincial Congress, 135.

[6] Foster, Bliss, and Danielson: Lincoln, Journals of Each Provincial Congress, 136–7.

[7] Danielson at Yale: Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College (New York: Henry Holt, 1896), 2:410–1.

[8] “Immediately proceeded”: Jedediah Foster to President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, April 23, 1775, Massachusetts Archives Collection, 193:57 (microfilm 7703487, images 272–3), Massachusetts State Archives. This letter is transcribed in Peter Force, compiler, American Archives, series 4 (Washington, D.C.: Clarke & Force, 1839), 2:378. Force modernized spelling and punctuation, and he read Danielson’s name as “Davidson.”

[9] Trumbull and the legislature: The Connecticut assembly met in New Haven on March 2–10, focusing on militia organization, with a plan to reconvene on April 13; Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, 14:388, 409. On April 4, Trumbull proclaimed there was no need for a second session that spring; Norwich Packet, April 6, 1775.

[10] Leaving Boston: James Warren to Mercy Warren, April 6–7, 1775, in Warren-Adams Letters [Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, vol. 72] (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917), 1:45.

[11] “To all whom”: Document sold by Heritage Auctions on June 8, 2017, historical.ha.com/itm/miscellaneous/joseph-palmer-historic-autograph-note-signed-jpalmer-19-april-1775-/a/997039-1064.s. There were several men named Sanger in Watertown at this time, including David Sanger, on the town’s October 1774 committee to equip two cannon, and Samuel Sanger, first sergeant of the militia company, so it is not possible to identify Palmer’s informant.

[12] Alarm letter: Palmer’s original letter does not appear to have survived. This transcription is based on “A true Coppy” filed in the United States Revolution Collection 1754–1928, Box 1, folder 22, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester. Other transcriptions say that Palmer wrote “near” ten o’clock, a detail this document’s transcriber probably skipped. Thanks to Joel Bohy for sharing an image of this page.

[13] Baldwin elected clerk: Early Records of the Town of Worcester: 1753–1783, Franklin P. Rice, editor (Worcester, Mass.: Worcester Society of Antiquity, 1882), 254.

[14] “A true copy”: Language based on surviving copies derived from Baldwin’s transcription with modern capitalization, punctuation, and abbreviation for clarity.

[15] “Isaac Russell”: This name appears in Alfred Minott Copeland, Our County and Its People: A History of Hampden County, Massachusetts (n.p.: Century Memorial Publishing Co., 1902) 1:75; and John Hoyt Lockwood, Westfield and Its Historic Influences, 1669–1919 (Westfield, Mass.: n.p., 1922), 1:531. Copeland’s second volume named Isaac Bissell correctly; 2:39–40. Henry A. Booth, “Springfield During the Revolution,” Papers and Proceedings of the Connecticut Valley Historical Society, 2 (1904), 291, also read that name as “Isaac Bissell”—but guessed that the letter was signed “Z. Palmer.” As this article shows, transcribing a handwritten document precisely can be a challenge, even in the best of conditions.

[16] Silas Deane journal: Christopher Collier, editor, “Inside the American Revolution: A Silas Deane Diary Fragment April 20–October 25, 1775,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin, 29 (July 1964), 86–7. Berthelson, “An Alarm from Lexington,” reports that the William L. Clements Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, holds a manuscript copy of Palmer’s letter signed by Silas Deane; it renders the name of Palmer’s messenger as “Mr. Isaac Bissell.”

[17] “set out for Lebanon”: Foster to Massachusetts Provincial Congress, April 23, 1775, Massachusetts Archives Collection, 193:57.

[18] “Writs are gone out”: Connecticut Committee of Correspondence (Williams, Wales, Trumbull) to President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress (Hancock), April 21, 1775, Massachusetts Archives Collection, 193:52–4 (microfilm 7703487, images 264-6), Massachusetts State Archives.

[19] Isaac Bissell’s military service: The Record of Connecticut Men in the Military and Naval Service During the War of the Revolution, 1775–1783, Henry P. Johnston, editor (Hartford: Adjutant-General of Connecticut, 1889), 23, 385, 552.

[20] Committee of safety action: Lincoln, Journals of Each Provincial Congress, 590.

[21] “he Could not alow”: Isaac Bissell to Joseph Palmer, March 20, 1776, Massachusetts Archives Collections, 303:162-1. Thanks to Joel Bohy for sharing images of these documents.

[22] Provincial congress action: Lincoln, Journals of Each Provincial Congress, 484.

[23] Bissell’s petition: Bissell to Palmer, March 20, 1776, Massachusetts Archives Collections, 303:162-1.

[24] Palmer’s petition: Joseph Palmer to Massachusetts General Court, March 22, 1776, Massachusetts Archives Collections, 303:162-2.

[25] Massachusetts General Court action: Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1982), vol. 51, part 1 (1775), 78, 96, 165. The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1918), 19:342. The payment went through John Bliss of Wilbraham, one of Massachusetts’s three delegates to Connecticut back in April 1775, presumably because he lived near Bissell’s home in Suffield.

[26] Isaac Bissell’s family: Benjamin W. Dwight, The History of the Descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass. (New York: John F. Trow & Son, 1874), 1:412–3. For Leavitt’s connection to Capt. Elihu Kent, see Nathaniel Goodwin, Genealogical Notes: or, Contributions to the Family History of Some of the First Families of Connecticut and Massachusetts (Hartford: F. A. Brown, 1856), 147.

[27] Isaac Bissell’s sales: Connecticut Courant, October 27, 1778. Connecticut Courant, April 10, 1781. Celebration of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Settlement of Suffield, Connecticut (Suffield, CT: 1921), 172.

[28] Artistic celebrations of Israel Bissell: Alice Schick and Marjorie N. Allen, The Remarkable Ride of Israel Bissell as Related by Molly the Crow: Being the True Account of an Extraordinary Post Rider who Persevered, illustrated by Joel Schick (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1976). Poems included Gerard Chapman, “Israel Bissell’s Ride” and Clay Perry, “I. Bissell’s Ride,” both published in the Berkshire Eagle newspaper in the 1950s. George Avison painted a mural of Israel Bissell at Roger Ludlow High School in Fairfield, Connecticut, in 1937. More recently, D. W. Roth painted an image for the Union Oyster House in Boston. Neither of those pictures includes Bissell’s name, though.

[29] Brooklyn and Norwich alerted: Scheide, “The Lexington Alarm,” 64.

[30] Trumbull alerted: I.W. Stuart, Life of Jonathan Trumbull, Sen., Governor of Connecticut (Boston: Crocker & Brewster, 1859), 173.

[31] Norwich transcription: The Norwich copy received from Daniel Tyler, Jr., of Brooklyn is reproduced in Scheide, “The Lexington Alarm,” opposite page 50.

[32] Norwich newspaper report: Norwich Packet, April 20, 1775.

[33] Norwich broadside: “Interesting Intelligence. Norwich, April 22, 1775, 10 o’clock, P.M. … Printed by Robertsons and Trumbull.” After helping to spread this alarm in 1775, the Robertson brothers became Loyalists, leaving Norwich for New York in 1776.

[34] Norwich to New London: Scheide, “The Lexington Alarm,” opposite page 56. In this document the name “Balding” had reverted to the more common and correct Baldwin.

[35] Lyme to New Haven: Elias Boudinot, Journal or Historical Recollections of American Events During the Revolutionary War (Trenton, NJ: C. L. Traver, 1890), 1. Boudinot or this book’s transcriber rendered Lyme as “Lynne” and Killingsworth as “Shillingsworth.”

[36] Williams to Johnson: “How the News of the Battle of Lexington Reached Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 27 (1903), 259–60. This article reproduces in facsimile a four-page manuscript in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. A photostat of this document is in the U.S. Revolutionary Collection, box 1, folder 22, American Antiquarian Society. Both Williams and Johnson had been chosen militia colonels and both would command Connecticut regiments during the war.

[37] New-York Gazette, April 24, 1775.

[38] “intelligence by Mr. Moorbach”: Scheide, “The Lexington Alarm,” 66–7.

[39] “requested to forward”: Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 27:261.

[40] Elias Boudinot recorded: Boudinot, Journal or Historical Recollections of American Events, 1.

[41] Thirty-eight signatures: Berthelson, “An Alarm from Lexington.” Merritt, “The Lexington Alarm, April 19, 1775,” 97–100.

[42] Maryland handbill: Scanned at www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.02800600/.

[43] Maryland Patriots: Merritt, “The Lexington Alarm, April 19, 1775,” 100–1. This article shows more April 1775 accounts following the same path to Maryland, endorsed at each stop by different men in the same way as copies of Palmer’s letter.

[44] News streams reaching North Carolina: Scheide, “The Lexington Alarm,” 70–4.

[45] London reprint: The Remembrancer, or Impartial Repository of Public Events (London: John Almon, 1775), 1:39, reflecting the spellings in the New-York Gazette.

[46] Israel Bissell: Edward Church Smith and Philip Mack Smith, “Descendants of Israel Bissell,” The American Genealogist, 27 (1951), 236–8.

[47] Israel Bissell’s military service: Record of Connecticut Men, 618. The commander of this company is listed as Captain Wolcott with no given name; he may have been Erastus Wolcott, Jr., son of the colonel whom Isaac Bissell had served under earlier in the year. Smith and Smith posit that the man listed on this roll might have been Israel Bissell’s namesake father because a family tradition said that man contracted dysentery during military service and died; “Descendants of Israel Bissell,” 234–7. Smith and Smith also refer to a receipt for five shillings in exchange for ten half-days of work before June 1775 from a Captain Stoughton as evidence of earlier military service by the younger Israel Bissell, but soldiers did not work half-days.

[48] Israel Bissell’s family: Vital Records of Middlefield, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1907), 66, 11; Vital Records of Hinsdale, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1902), 74. Smith and Smith, “Descendants of Israel Bissell,” The American Genealogist, 27 (1951), 237–8.

[49] Israel Bissell grave: Visible at www.findagrave.com/memorial/28200928/israel-bissell.

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

However you respond to the Mecklenburg controversy, May of 1775 was hardly...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Did no one before John Adams in 1819 cry plagiarism of the...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Outstanding article on a topic that deserves resolution and recognition