When Bryan McSweeny stepped ashore on Staten Island in August 1776, it must have looked like a paradise. He had spent the previous three years in Jamaica, in a tropical climate that was often fatal to Europeans; now, he saw a verdant landscape and felt temperatures similar to his native town of Macroom in County Cork, Ireland. But unlike peaceful Jamaica, which had avoided the violence of the recent Carib War, Staten Island was the staging point for a new British military offensive in the rebellious American colonies.

McSweeny was a private soldier in the 50th Regiment of Foot. He had volunteered for the army in 1768—during peacetime and for most of the American Revolution the British Army was an all-volunteer force—and now had eight years of soldiering under his belt including his three years in Jamaica. The regiment was ordered from that island to join the massive military buildup on Staten Island. But the disease-prone Caribbean climate had taken its toll, and the 50th was now under strength with many men unfit for service. There were other regiments on Staten Island that had been in North America for several years and also needed more men. Rather than add a newly-arrived regiment that was not fit for service into the order of battle, the army’s commander, Gen. William Howe, directed that the regiment be drafted.

Drafting, during this era, meant transferring soldiers from one regiment to another. This was a routine practice for the British army, a way to ensure that regiments on foreign service were brought up to strength with a portion of experienced soldiers instead of entirely with new recruits. In this case, the fit private soldiers of the 50th Regiment were drafted into other regiments on Staten Island; the rest would return to England, where the unfit men would be discharged while the officers, non-commissioned officers, drummers and fifers would begin an intensive recruiting campaign to rebuild the corps.

Bryan McSweeny and thirteen of his comrades joined the 22nd Regiment of Foot, which had been in America since arriving in Boston at the end of June 1775. Typical of drafts, he continued to wear the unform of his previous regiment, a red coat with black lapels, cuffs and collar instead of the red with buff worn by the 22nd; each soldier owned his uniform, and would not receive a new one until his regiment received a new annual clothing shipment late in the year. Being drafted meant remaining overseas, but it also meant receiving a new enlistment bounty, equivalent to about two months’ pay.

Within days of joining his new regiment, McSweeny was at war. The 22nd Regiment was part of the force that crossed from Staten Island to Long Island on August 22, then undertook the long nighttime march that outflanked rebel forces on August 27 in the Battle of Long Island; the regiment suffered only two casualties in this, one of the war’s biggest battles. The regiment landed on Manhattan Island at Kips Bay in mid-September, and was part of the garrison of the city of New York while the main army commenced operations farther north on Manhattan and then in Westchester County.

Serving in the same company of the 22nd Regiment as McSweeny was James Gardner, a native of England or Scotland who had enlisted in March 1775 as the regiment was preparing to leave Ireland for America. The two men were part of a detachment assigned to guard stores of provisions in the city starting at 8 o’clock in the morning on September 30. This was a 24-hour duty assignment, with two or three hours at a time spent standing sentry and the rest in a guard room, available to turn out in case of an alarm.

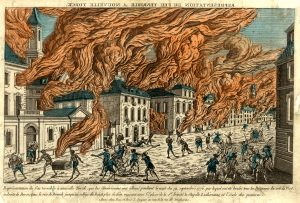

No alarm came that night for the provision guard, but there was a disturbance elsewhere in the city. A British army officer was awakened in the middle of the night by a disturbance outside the house where he lodged. He went to the window and saw a crowd around the cellar door below, which dispersed when he opened the window. But about an hour later, he heard noises coming from the basement. This was only days after insurgents had started fires that destroyed a third of the city, so the officer was especially concerned about more saboteurs.

He roused the homeowner, who roused his servant, and the three of them went to investigate. They found the outside cellar door had been forced open, and perceived sounds from within. The officer found a nearby sentry and had him stand guard at the cellar door, then the officer, the homeowner and the servant went inside. With a candle they went from room to room in the darkened basement, finding no one, until they noticed an inner door broken open. They peered through the doorway to a room where casks of wine were stored.

In the room were two men. “One of them was sitting with a bottle with the neck broke, between his legs; and there were a great many broken bottles laying about, and a strong smell of wine,” according to the officer. The homeowner recalled that “one of them hid away behind a Cask of bottled wine, and the other leaning over it, and the Cellar floor very wet, and many empty bottles broke and laying about,” and one of them “had a bottle in his hand or between his legs; they were both very drunk, and one was vomiting.” The three residents hauled the two intruders out of the basement—literally, as one needed to be dragged across the wine-wetted floor—took a bayonet from one of them (the other was unarmed), and proceed towards the main guard, the army post where disorderly people were put into custody.

One of the prisoners, the one who was standing when discovered, identified himself as James Gardner, on duty with the provision guard. He “walked very peaceably to the Guard and said that he was much ashamed of himself,” saying that the other prisoner “had brought him into the Scrape.” He then addressed the other prisoner directly, saying “he had told him what would happen.” When the group arrived at the main guard between two and three in the morning, the residents turned their prisoners and the bayonet over to the captain of the guard, and said they’d return in the morning “to give a Crime.” Gardner’s comrade was too drunk to be responsive, so the sergeant of the guard “in order to rouse him gave him some slaps on the face, with his hand.”

The homeowner arrived at the main guard at eight in the morning to lodge his complaint, only to find “to his great surprise” that both prisoners had been released. Remembering that Gardner was assigned to the provision guard, he went there and asked to see the men of the guard. Among them was Bryan McSweeny, who the corporal of the guard roused from sleep. He was immediately recognized, not only because he wore the uniform of the 50th Regiment, but also because his trousers were still wet with wine and he had marks on his face where the sergeant of the main guard had slapped him. He nonetheless had little recollection of the night’s events.

Gardner was not in the guard room. He had been posted sentry. The corporal of the guard took the homeowner to him, who recognized him, and Gardner acknowledged that he had been brought to the main guard just hours before.

Bryan McSweeny and James Gardner were tried by a general court martial on October 3 and 4, 1776, charged with “having broke into the house of Mr. Loring in the Town of New York.” In a common practice, they were tried together. The officer, the homeowner, the servant, the captain of the main guard and the corporal of the provision guard all testified for the prosecution. Their stories were all aligned, leaving little doubt that the soldiers were guilty of something; the only evidence in their favor was that “a side of mutton, a Turkey and a loaf of bread” as well as some bottles of wine were missing from the cellar, suggesting that others had also been marauding during the night.

Both prisoners denied having been the cellar. “Gardiner said that there being no room in the guard room to lay down, he went to walk the Street,” according to the trial record, “and Swyney said that his trowzers was wetted by a Canteen of Water that he had Spilt.” The thirteen officers who constituted the court were not impressed, found the two guilty, and sentenced them each “to receive one thousand lashes each on their bare backs with a Cat of nine tails,” a typical punishment for this sort of crime.

No information has been found to indicate whether these sentences were carried out in full or in part. Harsh though the sentence sounds, it was common for part or all of the lashes to be remitted or pardoned. Surgeons (military doctors) attended corporal punishments to make sure the prisoner was not in danger of death. It was, after all, corporal, not capital, punishment.

Both men continued their careers in the 22nd Regiment, which garrisoned Rhode Island from December 1776 through October 1779. James Gardner was not there the entire time; he died on October 24, 1777, of unknown causes.

Bryan McSweeny had a much longer career. When the war ended and the 22nd Regiment was reduced in size and ordered back to England, he was one of sixty-six men discharged in New York in September 1783. And he was one of forty-four who, rather than starting a new life as a civilian in the United States, immediately enlisted in another British regiment bound for Nova Scotia. Clearly he found the army an acceptable career in spite of his “scrape” and conviction seven years earlier. When the 54th Regiment left Nova Scotia in 1787, he was discharged once again, and once again re-enlisted, this time in the 20th Regiment of Foot—gaining his fourth enlistment bounty. He was discharged for the last time in October 1791, and crossed the Atlantic to go before the army’s pension examination board at Chelsea Hospital. Now forty-one years old, having spent twenty-three years as a soldier, he was awarded a pension, well-deserved after a long career in spite of his run-in with military discipline.

All of the material for this article is in the British National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, United Kingdom. James Gardner’s career is documented on the 22nd Regiment’s muster rolls, WO 12/3872. Bryan McSweeny’s career is there, as well as on the rolls of the 50th, 54th and 20th Regiments, and his discharge, WO 121/12/371. The proceedings of their court martial are in WO 71/83 p. 41 – 48. Details about British army enlistment, drafting, and pensions can be found in Don N. Hagist, Noble Volunteers: The British Soldiers Who Fought the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Wesholme, 2020).

5 Comments

Your use of primary documents really makes this come alive!

Great job, Don!

Wonderful stuff, thank you! I’ve just finished the first book of my family trilogy, dealing with Lt (brevetted Captain) Robert Carlyle, Royal Artillery, and his service in Newfoundland and Boston during the siege. The 65th Rgt of Foot, stationed in Boston, and under his command at Placentia have preserved wonderful details of the punishments meted out for breaches of discipline – “being beastly drunk in the street”, “making away with his necessarys” (sic), which I found invaluable. Carlyle was one of the R.A. who landed at Staten Island, also. Thanks again.

My ears pricked up at the mention of the homeowner’s name: is this Loring connected to Joshua and Elizabeth Loring?

The homeowner, Joshua Loring, testified in the trial, but there is no information in the trial record to further identify him as the Joshua Loring that was married to Elizabeth and who became a British commissary officer. The trial doesn’t give the specific location of the home. The Joshua Loring of Elizabeth Loring fame was a native of Boston and came to New York with the British army, arriving in Manhattan in mid September 1776. The events described in the trial occurred only two weeks later, not much time to acquire a home unless it was already in the family. But, without further information, we can’t rule anything out.

Don, thank you for your citations. Every specific reference to a WO record group is one less needle in a very large haystack for researchers who can’t quite make it to TNA to explore. As always, your research and writing are exceptional.