As an integral part of the American governing system, the United States Congress added the Bill of Rights to the Constitution on December 15, 1791. Whether by accident or design, that same year the British House of Commons also approved the Constitutional Act of 1791 as the governing structure for its newly acquired territory of Quebec, which it had divided into the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. Owing to this coincidence in timing, from the beginning the United States and the two Canadian provinces, while sharing a common border, operated under entirely different governing philosophies.

Over the ensuing years a growing awareness had taken place in both provinces of the advantages along with the disadvantages of these two very different forms of government. As a result, reform movements emerged in Upper as well as in Lower Canada with the aim of requesting from the British Parliament changes in the provinces’ governing structure. To specify the nature of the desired changes, toward the end of July 1837, the Reform Party of Upper Canada took its lead from the Declaration of Independence and produced a lengthy document with the following introductory statement.

The time has arrived, after nearly half a century’s forbearance under increasing and aggravated misrule, when the duty we owe our country and posterity requires from us the assertion of our rights and the redress of our wrongs, [therefore, we request the] right conceded to the present United States, at the close of [their] successful revolution, to form a constitution for themselves . . . the loyalists with their descendants and others, now peopling this portion of America [Upper Canada], are entitled to the same without the shedding of blood—more they do not ask; less they ought not to have.[1]

The goal of the Reform Party document, which set forth the principal grievances identified by the Party, was to engage the governor-general of Canada in a series of discussions followed by negotiations. The hope was that by enumerating the many grievances that had troubled the residents of Upper Canada, a different constitution would emerge to replace the Constitutional Act of 1791.

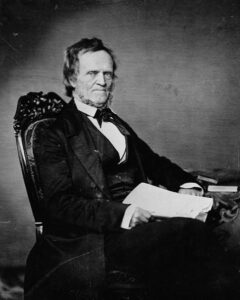

Recognizing the need to gain widespread public support for the Reform Party’s initiative, William Lyon Mackenzie was assigned the role of Agent and Corresponding Secretary. Known as an impassioned orator, “He was to be a supreme itinerant organizer, and was to go about the country stirring up opposition to the Government.”[2] Although Mackenzie had accepted this responsibility and typically adhered to the Party’s goal of discussion and negotiation, during his speeches he had a decidedly different underlying goal in mind. Also inspired by the outcome of the American Revolution,

he adapted his oratory to his audience. Where he knew that he would encounter little or no opposition he was much more outspoken than where the feeling was less favorable to him. Wherever he felt that he could carry his audience with him he boldly advocated separation from the mother-country, and the establishment of elective institutions under an independent Government.[3]

Mackenzie’s hidden purpose in conducting these rallies was to attract a sufficient number of supporters to stage an uprising against the Crown. In the words of historian R.A. Mackay, “There is little doubt that Mackenzie hoped by rebellion to establish a frontier Utopia in Upper Canada.”[4]

To further his cause and inspire his followers, on November 15, 1837, Mackenzie circulated a draft constitution of his own making which began with a preamble that closely resembled the tone and purpose of the United States Constitution.

We, the people of the State of Upper Canada, acknowledging with gratitude the grace and beneficence of God, in permitting us to make choice of our form of Government, and in order to establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of civil and religious liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do establish this Constitution.[5]

Unlike the American Constitution, though, which contained seven articles and dealt solely with the means for organizing a government, Mackenzie’s constitution contained more than eighty clauses, the majority of which were aspirational and, like the Declaration of Independence, served as rallying cries for an insurrection. As the following examples illustrate, a number were calls for individual freedom (clauses 1, 7, and 8), others dealt with such matters as the abolishment of hereditary rights (clauses 6 and 16), and still others were concerned with the need for public elections along with the need for a more democratically controlled government (clauses 22 and 59).[6]

Clause 1. The legislature shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, or for the encouragement or prohibition of any denomination.

Clause 6. No hereditary emoluments, privileges, or honours shall ever be granted by the people of this State.

Clause 7. There shall neither be slavery nor involuntary servitude in this State. . . . People of Colour, who have come into this State . . . shall be entitled to all the rights of native Canadians, upon taking an oath or affirmation to support the constitution.

Clause 8. The people have a right to bear arms for the defense of themselves and the State.

Clause 16. The real estate of persons dying without making a will shall not descend to the eldest son to the exclusion of his brethren, but be equally divided among the children, male and female.

Clause 22. The legislative authority of this State shall be vested in a General Assembly, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Assembly, both to be elected by the People.

Clause 59. The Governor shall be elected by the People at the times and places of choosing members of the legislature.

Mackenzie’s rallies, staged during the summer and fall of 1837, involved some 200 meetings principally confined to several townships in Upper Canada.[7] With the help of followers gained through these meetings, Mackenzie then launched on December 7 what is known today as the Mackenzie Rebellion. The same was true for Lower Canada where a similar uprising unfolded, though under a different leadership.[8]

Among the many shortcomings in the Constitutional Act of 1791 for both Upper and Lower Canada was the requirement for a Legislative Council. Modelled after the House of Lords in England, its members were not elected but were appointed for life, “directed from London and designed to serve imperial ends,” and granted heredity titles by the Crown.[9] Its members also were strongly opposed to the American governing system, were extremely devoted to the British way of life, and believed that “Government did not, in their view, derive its authority from the consent of the governed, but from the King, from history and from religion.”[10] According to a list compiled by Mackenzie in 1833, most of the Council members in Upper Canada were extremely wealthy and closely related to each other through kinship or marriage.[11] As a result of these two components, the term Family Compact was coined to describe its operation.

The Constitutional Act also called for a further body known as the Legislative Assembly that resembled the British House of Commons. Unfortunately, many of the bills that arose in the Assembly were often overruled by the Council.

Although the assembly could initiate legislation and was, indeed, the main legislative body in the province, its bills could be rejected by the legislative council or the lieutenant-governor of the British government. Hence, from the outset, the possibility was that a particular house of assembly would be at loggerheads with other centers of governmental authority, engaged in a struggle it could not hope to win.[12]

Needless to say, owing to this factor alone, coupled with the reformers’ strong belief in the need for a non-hereditary, democratically controlled legislature (see clause 6 and 22 in Mackenzie’s constitution) it is not surprising that, with the passage of the Constitutional Act of 1791, the seeds for an uprising had clearly been sown.[13]

The Rebellion

During the morning of December 7, 1837, Mackenzie launched his rebellion north of Toronto. Upon hearing a rumor that Mackenzie had been successful, Dr. Charles Duncombe, a compatriot of Mackenzie, organized a similar rebellion several days later southwest of Toronto in the vicinity of Brantford, Norwich, London, and St. Thomas.[14]

Despite the enthusiasm generated by their leaders, both phases of this rebellion were largely over in a few days. The cause of Mackenzie’s defeat was that far fewer joined his uprising than he had anticipated. It was also poorly organized, equipped, and therefore easily overcome.[15] Duncombe’s defeat, on the other hand, was “hurriedly organized [and] ill-coordinated.”[16] Of added importance, and contrary to what had been anticipated, “the majority of colonial residents [in Upper Canada] stayed loyal to the queen, even when they disliked her colonial administrators.”[17]

Mackenzie left Upper Canada shortly after his defeat and fled to Buffalo, New York, where he arrived on December 11.[18] Duncombe, who also fled Upper Canada but did so following Mackenzie’s departure, went to Detroit, Michigan.[19] The reason these locations were chosen was to take advantage of a sympathetic American volunteer Patriot Movement that had emerged in the general vicinity of both cities once it became known that there were Canadians who were as opposed to British rule as their American counterparts.[20]

In 1837, Americans along the border from Maine to Wisconsin still harbored enmity for the British government [and] . . . wanted the continent purged of any vestige of English despotism . . . Americans had no quarrel with Canadian colonists, who were kith and often kin . . . Many Upper Canada merchants and farmers had emigrated from the United States and brought their democratic ideals and republican views with them . . . Brothers in difficult times, the Canadian rebellion offered an opportunity for young [American] men to be heroes and old [American] men to kick out the monarchists.[21]

Within days after Mackenzie and Duncombe arrived in the United States an American Patriot force occupied the Upper Canada-owned Navy Island in the Niagara River.[22] As a show of appreciation, Mackenzie wrote to the citizens of Buffalo, that they “have proved to us the enduring principles of the Revolution of 1776, by supplying us with provisions, money, arms, ammunition, artillery, and volunteers.”[23] Another assault took place on January 8, 1838, near an island in the Detroit River[24] and still another occurred in roughly the same location on February 24.[25] Writing to a sympathizer in Rochester at the end of January with the hope of further extending these assaults, Mackenzie claimed that,

From Belleville downwards, to the Cedars, a distance of 200 miles, [there existed] an exposed and undefended [Canadian] frontier—to defend it adequately would be ruinous to the Govt. of Great Britain, still more [so] to that of Canada . . . The end, with a little perseverance on our part will be a break up [of Canada], and I mean to stick to [these assaults] like wax as do others of our party.[26]

Despite Mackenzie’s unbridled optimism, neither he nor his American followers were prepared for the level of resistance provided by the local militia and the British military. One of the most unusual of the British counter offensives took place in March when an American Patriot force landed on the British-owned Pelee Island near the middle of frozen Lake Erie. “Military history does not record many such episodes as a cavalry charge across a frozen lake taking along two six-pounder guns with the lines wheeling when the leader’s horse breaks through.”[27]

The most decisive of the Canadian/British offensives occurred in the fall. Known as the Battle of the Windmill, the initial American assault took place on November 8, 1838, near the town of Prescott in Upper Canada. In preparation for the final aspect of the assault, the 200 to 300 American volunteers were told by their leader “who delivered a fiery speech, that between 20,000 and 40,000 [additional American] men would invade Upper Canada . . . and once on the soil of that province, they would be supported by nine of every ten Canadian citizens and three-quarters of the troops in garrison.”[28] Unfortunately for the volunteers, this information was totally false. When the actual invasion began on November 16 the volunteers quickly learned that they had been seriously deceived both in terms of the anticipated level of American support, which never arrived, and that very few Canadians were truly sympathetic with Mackenzie’s views. The Americans encountered a Canadian led local militia force together with the British 38th Regiment of Foot and Royal Marines plus the 93rd Highland Regiment of Foot. When the battle was over on November 17, “of the 250 [Americans] who may have invaded Upper Canada during that bloody week, perhaps as many as 50 were dead and 160 were eventually captured (including 17 wounded). The remainder had escaped back to the United States.”[29]

Outcome

Although the Mackenzie Rebellion that took place on the Canadian side of the border lasted only a few days, with the help of Mackenzie’s American-led counterparts, his overall rebellion lasted nearly one year. At the end of this combined undertaking, in addition to those killed, 1,034 men had been arrested by the British. Of this number 92 were sentenced to hard labor and sent by ship to the penal colony at Van Diemen’s Land while 20 others were hanged. Nearly 75 percent of those in the latter two groups were from the United States.[30]

In one of the anomalies of war, Mackenzie was captured and brought to trial in May 1839, not in Upper Canada where the British government had issued a 1,000-pound reward for this capture,[31] but in New York State. He was charged with

setting on foot a military enterprise at Buffalo, to be carried on against Upper Canada, a part of the Queen’s dominions, at a time when the United States were at peace with Her Majesty; with having provided the means for the prosecution of the expedition; and with having done all this within the [British] dominion and territory, and against the peace, of the United States[32]

The trial, which lasted two days, was held in Canandaigua, New York. Mackenzie was fined ten dollars and sentenced to eighteen months in prison. Following his release, he remained in the United States. Mackenzie was granted amnesty in 1849 by the Reform ministry of Upper Canada and returned to Toronto in May 1850 where he resided until he died on August 28, 1861.[33] “A procession half-a-mile long followed his body to the Toronto Necropolis where [he] was buried in the north-east corner.”[34] The house where he lived at the time of his death is now owned by the city of Toronto, run by the Toronto Historical Board, and is open to the public.

Aftermath

The British Parliament was alarmed by the uprising. Shortly after the Battle of the Windmill an inquiry was launched to determine its cause along with the steps that were needed to prevent any future uprisings of a similar nature. In charge of the inquiry was Lord Durham who issued a report along with a suggested solution.

The whole party of the [Upper Canada] reformers, a party which I am inclined to estimate as very considerable . . . has certainly felt itself assailed by the policy pursued [by the Crown]. It sees the whole powers of Government wielded by its enemies [Parliament and the Crown], and it imagines that it can perceive also a determination [by the Crown] to use these powers inflexibly against all the objects which it most values . . . and that the party called the ‘family compact’, which possesses the majority in both branches of the legislature, is, in fact, supported at present by no very large number of persons in any party . . . I have no reason to believe that anything can make them [the population of Upper Canada] generally and decidedly desirous of separation, except some such act of the Imperial Government as shall deprive them of all hopes of obtaining real administrative power[35]

For Upper Canada to remain within the British fold, Durham claimed that the British government must surrender to the colonies the full authority to conduct their own internal affairs. It must also be prepared to see those affairs administered by their own elected representatives and carried out as best they see fit.

Thus, he argued for what has since become known as “responsible government,” the cabinet system that was already in operation in Great Britain. In the colonies this principle would mean that the governor must draw his executive advisors from men who had the confidence of the majority in the Assembly, that he must be prepared to change his advisers when they lost the confidence of this majority, and that as long as they retained this confidence he must carry on the government, in all internal matters, according to their advice, despite differing views that he or the British government might have. If this principle were not accepted, wrote Durham, the colonies would surely be lost; if it were [accepted], their connection with the mother country would be permanent, and beneficial to both.[36]

Through the office of a newly appointed Governor-General of Canada, Charles Poulett Thomson (later known as Lord Sydenham), this is precisely what happened! As part of his mandate Thomson, who arrived in Canada in October 1839, initiated two fundamental changes. The members now chosen to be part of the Legislative Council in Upper Canada would no longer be entitled to hold their positions for life, and any local replacements would not be part of a Family Compact. Some have even gone so far as to say, “that [Lord] Sydenham was making a clear statement that the power of the [Upper Canada] Toronto Family Compact was smashed beyond repair.”[37]

Parenthetically, nearly thirty years after the rebellion was over, the political significance of the Durham Report’s recommendation concerning the Family Compact was further extended to the federal level. At the end of a lengthy debate in 1865 the Canadian parliamentary minutes contained the following recommendation.

The first selection of the Members of the Legislative Council [for the country as a whole] shall be made from the Legislative Councils of the various Provinces so far as a sufficient number be found qualified and willing to serve; such Members shall be appointed by the Crown at the recommendation of the General Executive Government, upon the nomination of the respective Local Governments, and in such nominations due regard shall be had to the claims of the Members of the Legislative Council of the opposition in each Province, so that all political parties may, as nearly as possible, be fairly represented.[38]

Although the Crown would still have a say in who should become members of the federal Legislative Council, the Crown’s choice would now be confined to candidates nominated at the local level. By also asking the Crown to strive for balance among the political parties when making its choice, this further step would now eliminate, also at the federal level, any attempt to form a Family Compact.

It is not surprising, in view of the above, that on the 100th anniversary of the release of the Durham Report, the Canadian Historical Review devoted an entire issue to an assessment of the Report’s many achievements. Lord Tweedsmuir, the Governor-General of Canada, wrote in the issue’s introductory article that “no state paper ever issued by the British government has had a more profound influence on the course of Canadian history or on the development of British policy throughout the empire as a whole.”[39] Similarly, the author of the final article concluded that,

Durham’s Report remained and remains the epitome of responsible government . . . Without compromising the canons of historical scholarship we have tried in these commemorative lectures to honour his name and to demonstrate anew the fulfilment of the faith in which he died that Canada would one day do justice to his memory.[40]

Given these extremely positive comments, how did Mackenzie view the Report? According to Charles Lindsay, who published a two-volume biography of Mackenzie the year after his death, he would have been quite pleased with the recommendations. As his son-in-law, Lindsay had access to an extensive range of letters, notes and files kept by Mackenzie throughout his life. Based on this material Lindsay claimed that Mackenzie was not only in favor of responsible government, “he put forward responsible government as a principal of vital importance and as a needed reform.”[41] He was also quoted by Lindsay as having said,

The people of this Province neither desire to break up their ancient connection with Great Britain, nor are they anxious to become members of the North American Confederation; all they want is a cheap, frugal, domestic government, to be exercised for their benefit and controlled by their own fixed land-marks, they seek a system by which to ensure justice, protect property, establish domestic tranquility, and afford a reasonable prospect that civil and religious liberty will be perpetuated, and the safety and happiness of society affected.[42]

If Lindsay’s comments are correct, an immediate question arises: how is it possible to reconcile the above with the many republican-oriented statements in Mackenzie’s 1837 draft “constitution” along with his stated goal at the outset of the rebellion to separate Upper Canada “from the mother-country”? Two closely connected answers come to mind. First, Mackenzie may have chosen to follow the American model of revolution and launch a rebellion because, at the time, he may have felt that only through an armed uprising would it be possible to remove the deleterious effects of the Family Compact on the progressive thinking advanced by the Legislative Assembly. Second, he may also have felt that only through the clauses in his draft constitution and in the arguments advanced in his pre-rebellion rhetoric would it be possible to obtain an uprising of sufficient strength to bring about what he considered an essential change in the governing structure that followed from the Act of 1791. In essence, it could be argued that although he clearly lost on the battlefield, because his uprising led to the Durham Report which, in turn, produced what he so desperately desired, in the end Mackenzie did achieve that which he favored from the very beginning: responsible government for the people of Upper Canada and the right for its residents to remain within the British fold.

[1] Charles Lindsey, The Life and Times of Wm. Lyon Mackenzie (Toronto, ON: CW. P.R. Randall, 1862), 2:334.

[2] John Charles Dent, The Story of the Upper Canadian Rebellion (Toronto: ON: C. Blackett Robinson, 1885), 368.

[3] Ibid., 369.

[4] R.A. MacKay, “The Political Ideas of William Lyon Mackenzie” The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, Vol. 3 No. 1 (February 1937), 20.

[5] Colin Read and Ronald J. Stagg, The Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada: A Collection of Documents (Ottawa, ON: Carleton University Press, 1985), 96.

[6] Ibid., 96-101.

[7] Edwin C. Guillet, The Lives and Times of the Patriots (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1968), 10.

[8] Jean-Paul Bernard, The Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 in Lower Canada (Ottawa, ON: Canadian Historical Association,1996).

[9] Phillip A. Buckner, The Transition to Responsible Government (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1985), 164.

[10] Gerald M. Craig, Upper Canada: The Formative Years 1784-1841 (Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 1963), 110.

[11] Rick Salutin and Theatre Passe Muraille, 1837 William Lyon Mackenzie and the Canadian Revolution (Toronto, ON: James Lorimer & Company, 1976), 50-51.

[12] Colin Read, The Rising in Western Upper Canada, 1837-1838: The Duncombe Revolt and After (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1982), 5.

[13] While the Family Compact is recognized as a major contributing factor to the Mackinzie Rebellion, there were others such as the Clergy Reserves that gave also rise to much dissatisfaction. For a detailed discussion of these factors see Read and Stagg, The Rebellion of 1837, 1985.

[14] Read, The Rising in Western Upper Canada, 9.

[15] Craig, Upper Canada, 249.

[16] Read, The Rising in Western Upper Canada, 205.

[17] Shaun J. McLaughlin, The Patriot War Along the Michigan-Canada Border: Raiders and Rebels (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2013), 153.

[18] Craig, Upper Canada, 250.

[19] McLaughlin, The Patriot War, 28.

[20] Donald E. Graves, Guns Across the River: The Battle of the Windmill, 1838 (Fitchburg, WI: Robin Brass Studio, 2013), Chapters 3 and 4.

[21] McLaughlin, The Patriot War, 10-11.

[22] Ibid., 30.

[23] Lindsey, The Life and Times of Wm. Lyon Mackenzie, 2:365.

[24] McLaughlin, The Patriot War, 46.

[25] Ibid., 60.

[26] Fred Landon, Western Ontario and the American Frontier (Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart Ltd. 1967), 176.

[27] Ibid., 179.

[28] Graves, Guns Across the River, 69.

[29] Ibid., 181.

[30] McLaughlin, The Patriot War, 167-174.

[31] David Flint, William Lyon Mackenzie: Rebel Against Authority (Toronto, ON: Oxford University Press, 1971), 161.

[32] Ibid., 169.

[33] Ibid., 179.

[34] Ibid., 184.

[35] Gerald M. Craig, Lord Durham’s Report (Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 1963), 92.

[36] Ibid., vi.

[37] Michael S. Cross, A Biography of Robert Baldwin: The Morning-Star of Memory (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2012), 48.

[38] Parliamentary Debates on the Subject of Confederation of the British North American Provinces, 3rd Session, 8th Provincial Parliament of Canda (Ottawa, ON: Edmond Cloutier, 1865), 1028.

[39] Lord Tweedsmuir, “The Centenary of the Publication of the Lord Durham’s Report,” The Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 20 No. 2 (June 1939), 114.

[40] Ibid., 191,194.

[41] Lindsay, The Life and Times of Wm. Lyon Mackenzie, 1:179.

[42] Ibid., 178-179.

Recent Articles

The New Dominion: The Land Lotteries

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...