As 1776 was ending, a group of about 225 American prisoners was released from the British prisons in New York City to be sent to Patriot-controlled New England.[1] Most of them were enlisted soldiers from Connecticut, but there were also a few from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, and several officers.[2] They had so far survived the battlefield and the deprivations of imprisonment, but their greatest trial lay before them. They still had to get home.

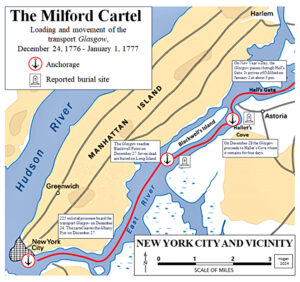

On December 24, the men were hastily paroled and marched down to the docks on the Lower East Side where a former merchantman called the Glasgow was moored. Before the Revolution, the ship had carried commercial goods but it was now serving as a military transport.[3] Many writers have dubbed the Glasgow a “prison ship” but in this instance, it was being used as a conveyance. Its belly was large enough to accommodate—albeit quite deficiently—the large number of paroled men who were put aboard. The ship’s master, Capt. Robert Craig, planned to make for the small coastal port of Milford under a flag of truce.[4] To get there, Craig would have to squeeze his way up the narrow East River, through the treacherous Hell’s Gate into the contested waters of Long Island Sound.[5] Under ideal conditions, the trip would have taken less than a week. Unfortunately, a series of misfortunes would keep the prisoners on board for eleven hard days.[6]

There was little chance the Americans would rise up. To win their parole they had pledged to refrain from any adverse action against the Crown. It would not only be considered dishonorable for them to go back on their word; parole violators also faced swift retaliation from their British captors—and possible punishment by Patriot authorities.[7] In any event, many of the prisoners were in a weakened state, their bodies wasted from the short rations and foul conditions in the city’s hellish military jails. No matter how dire their circumstances became, the prisoners knew the Glasgow and its crew provided their only means of escaping British-held territory.

Before dark on Christmas Eve, a lieutenant from Norwich named Jabez Fitch went down to the docks. Like other captive American officers, he was allowed by the British to move freely through the city. Weeks earlier, the British had granted leave to Maj. Levi Wells of Colchester so that he could raise funds and collect mail back in Connecticut for the prisoners. Wells had only just returned and some of the items he brought back were meant for men on the Glasgow. At the pier, Fitch passed the mail to Sgt. Rufus Tracey, an old friend of his from the Norwich area.[8] The news from home must have been a rare diversion for the enlisted soldiers on the ship.

Christmas morning brought little joy to the prisoners on the Glasgow that had yet to set sail. Lieutenant Fitch wrote in his diary that when he went down to the Albany pier to visit them, he learned twenty-one prisoners had died in the city overnight, including two on the ship.[9] Later in the day, another officer diarist from eastern Connecticut joined the enlisted men on the Glasgow.[10] Lt. Oliver Babcock had been keeping a daily journal since he was taken captive when Fort Washington fell in November. He would continue to document his journey home, thereby creating a unique contemporaneous record of the cartel ship’s passage to Milford. His December 25 entry “on board the ship Glasco” includes one error; he mistakenly identified the shipmaster as James, rather than Robert Craig as the captain’s name appears elsewhere. On Christmas Day, Babcock allowed himself a luxury not available to the common soldiers on the ship. He briefly returned ashore to have dinner with “Mrs. Cassander” and Lt. Aaron Stratten, a fellow officer who had not yet been exchanged. On the 26th, the same winter storm General Washington encountered at Trenton fell upon New York City. With the “rainy icey weather” delaying the ship’s departure, Babcock did what he could to relieve the suffering of his fellow soldiers, likely with his own funds. Lieutenant Babcock’s wife Marcy had sent him some “hard money,” meaning gold or silver coins, which had taken her “much trouble to procure.”[11] Babcock bought wine for the sick and bread that was passed around in the transport’s dark hold.[12]

It was not until Friday, December 27 that the Glasgow finally cast off, but it sailed only a few miles to Blackwell’s Point on what is today known as Roosevelt Island. In his characteristic stoic style, Lieutenant Babcock impassively noted that seven dead were buried on nearby Long Island.[13] On the 28th the cartel ship advanced a short distance to Hallet’s Cove where two dead were buried ashore. The ship remained idle for several more days; stranded, said Pvt. Thomas Tryon of Middletown, by unfavorable winds.[14] The stagnant hours of cold and hunger continued to drain the prisoners’ strength, and more of them took their final breaths. One of these was Sgt. Joseph Barnes, a militiaman taken at Fort Washington. His passing was especially poignant. Back in September, his wife Thankful had died after giving birth to their fourth child.[15]

It is not known how much food was initially taken for the voyage, but the surviving accounts indicate it was inadequate both in quantity and quality. Packed below the transport’s decks, the shivering prisoners were fed some “black, coarse broken bread” and a reduced serving of pork.[16] During the delay at Hallet’s Cove, Lieutenant Babcock tried to supplement the men’s meager rations by buying a sheep and twenty gallons of molasses from the locals.[17]

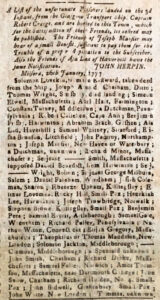

On New Year’s Day of 1777, the Glasgow again set sail. As it passed through Hell’s Gate, it nearly suffered disaster. Its wooden hull struck a rock, but said Babcock, it “got off safe.” Finally, on January 2 in the dwindling daylight, the transport dropped anchor in Milford Harbor. By then, about 200 of the Americans were still alive.[18] According to Lieutenant Babcock, it was on the 3rd that the “poor sick men” were put ashore.[19] Since the Glasgow would have anchored away from the shore, the Americans were probably shuttled to the beach in a ship’s boat. They carried with them the lifeless bodies of Pvt. Joseph Arnold of East Hampton and Pvt. Solomon Lovekin of Ipswich, Massachusetts. Even as they reached the friendly shore, the luckless men suffered still more hardship. Somehow, Pvt. Thomas Wright of Simsbury “died landing.”[20] Oliver Woodruff, a private from Capt. Bezaleel Beebe’s Litchfield company later recalled that “quite a number of us had our feet frozen,” possibly from wading ashore in the surf or walking through snow.[21]

As the men filed into Milford, their “rueful countenances” bespoke the harsh treatment they had experienced in New York.[22] Alarmingly, some of the men were also showing signs of smallpox. The townsfolk rightly feared the contagion would spread and they forbid the arrivals to stay in their homes.[23] Even so, they did their best to care for them. Private Woodruff recalled, “Soon after we got there they brought us three corn baskets full of boiled beef, potatoes and bread, and every one that was able to help himself got as big a piece as he could.” Sadly, the prisoners’ withered bodies were not ready for such a feast. Wrote Woodruff, “Nineteen died that night from over eating.”[24] Woodruff’s assessment may have been prescient. During World War II, doctors learned that starving patients could die if reintroduced to food too quickly.[25] Known as Refeeding Syndrome, this paradoxical toxic reaction would have been unknown to the well-meaning people of Milford. In the days ahead, smallpox would claim still more of the former prisoners. In all, forty-six men of the exchanged prisoners were buried in Milford’s cemetery.[26]

Those who were able wasted no time leaving for home. On January 4, for example, Lieutenant Babcock had a “physick” and then set out on foot.[27] For some, the journey proved too difficult; there were harrowing reports of men dying along the road.[28] Their exodus also spread smallpox among the civilian population. In Stratford, Capt. John Brooks, the local barrack master, felt compelled to help the forlorn veterans who were passing through his town. Despite taking “every precaution,” the disease broke out in Brooks’ own family and then through the town, infecting hundreds of residents.[29] Private Tryon recalled that as he walked back to Middletown, passing strangers avoided him. Although he was able to make it home, he soon fell terribly ill. He barely pulled through.[30] Lieutenant Babcock was not so lucky. Though he joyfully returned to his Stonington farm, he had carried the deadly virus with him. He died of smallpox on January 24. His three young children also became infected and two followed him to the grave.[31]

Back in Milford, those too sick to travel were sheltered in the meeting house, tended by the town’s physician, Dr. Elias Carrington. A local mariner named Capt. Stephen Stow understood it was risky, but he volunteered to help Doctor Carrington in the makeshift hospital.[32] There are also reports that family members went to Milford to care for their loved ones. According to a family history, fifty-seven-year-old Ephraim Bidwell journeyed from Glastonbury to tend to his sick son Joseph. Smallpox would claim both men, as well as the selfless Captain Stow.[33]

There are hints that some of those too frail to walk home were carried out by ship. Sgt. Heman Baker, a Tolland levy, was on a list of those initially said to be too sick to leave Milford.[34] He was reportedly taken up the Connecticut River by “a vessel” as far as the Hockanum landing in East Hartford.[35] Enfeebled by smallpox, Baker could go no further, and he died on January 21. There may have been others who had traveled with him. Another Tolland levy named Pvt. George White had also been on the list of the sick. A family history states he died in East Hartford on January 17.[36] Baker was laid to rest along Willow Brook at the edge of a farmer’s field. White may have been buried at the same spot.[37] Another of the returning sick who died around the same time was twenty-five-year-old Pvt. Aaron Drake. His grave is ten miles to the north in what today is part of South Windsor.[38] Sgt. Elisha Benton of the 17th Connecticut Regiment was able to reunite with his family in Tolland but he was soon overcome by the pox. His sweetheart Jemima Barrows reportedly died after caring for him.[39] The two are buried near each other on the Benton homestead.[40] Their loss only compounded the Benton family’s grief. Elisha’s brother Pvt. Azariah Benton had died on December 29 aboard the ship.[41]

One of the most emotionally charged themes associated with the Milford cartel is the allegation that the British had intentionally sent smallpox carriers aboard the transport to infect the other prisoners and the civilian population in Connecticut.[42] One of the starkest examples of this view was expressed by Pvt. Elijah Stanton of Preston. In his 1832 pension application, Stanton attested that the prisoners “were put on board a sloop at New York & kept there eleven days & then a man brought on board sick of the small pox & almost all the prisoners took it & died applicant had it—He thinks it was the object of the British to kill them by this maneuver—They were then set on shore, & applicant got home, and the second day after he got home, he broke out of the small pox—Got home 9th day of January 1777.”[43] A similar view of British malevolence came from Col. John Chester two weeks after the cartel ship disgorged the afflicted in Milford. In a letter to General Washington’s Aide-de-Camp, Col. Samuel Webb, Chester stated, “Most who have got home in the neighboring towns, are taken with the small pox, which undoubtedly was given them by design.”[44]

There is no doubt that men on the Glasgow had been exposed to smallpox and that the contagion spread to civilians in Connecticut. What is not certain is that this happened as the result of a British plan. It took some time for the notion of British biological warfare to emerge. The first story of the cartel ship’s arrival in the January 8 Connecticut Journal described the prisoners’ woeful condition but made no mention of smallpox. Nor did Lieutenant Babcock speak of the illness in his journal, though he must have known the disease had broken out on the transport. As Oliver Woodruff put it, “For several days previous to landing we had the small pox aboard.” Other than a curious reference to taking a “physick” in Milford, the noble Lieutenant Babcock related no concern that his health was at risk or that he could pose a threat to others. On his way back to Stonington, he took meals in public houses and he ate and slept in the homes of acquaintances, at least one of whom was a physician.[45] He even spoke before “Both houses of Assembly” in Middletown. If he was beginning to experience any ill effects he never said so. But the variola virus was probably already secretly multiplying inside his body, like a gathering army waiting to strike.

It could be that just a few men had developed pustules during the voyage, even though many others had unknowingly been infected. With each passing day, more showed outward symptoms but by then, virus carriers had already taken to the roads, oblivious to what lay in store. As word spread of their deaths, and of innocent civilians becoming sick, the accusations against the British began.

What little is known about the preparations for the Milford cartel suggests it was not intended to be a death ride. The Glasgow had previously held prisoners in New York but it is a stretch to equate it with the Wallabout Bay prison hulks like the Jersey. In early November 1776 Col. Ethan Allen and twenty-four other prisoners transferred from Halifax were put aboard the Glasgow in New York harbor.[46] Allen was generally quite critical of his treatment in British hands, but in a letter to General Washington, he spoke better of the “Transport Cal’d the Glasgow . . . where I am well Used, and have in great measure recover’d my Health.” Elsewhere, Allen wrote that “Capt. Craige” and his lieutenant shared their cabin and rations with him and that he “was in every respect well treated.”[47] There are also indications that the severely sick were kept off the ship. For example, the men from Captain Beebe’s Litchfield company who were “too ill” were not allowed to go home on the Glasgow. Most of Beebe’s men who were left behind died in New York of smallpox.[48]

There is no record of how the men who went aboard the ship were chosen. According to Lieutenant Fitch, the group included “what privates of the 17th Regt remained living,” most of whom had been prisoners since the end of August.[49] Others were from assorted units who were captured at varied times, including militiamen taken at Kip’s Bay and Fort Washington. Sgt. David Hendrix of New Canaan was wounded and captured at White Plains on October 28 and Sgt. Richard Holden of Colonel Israel Hutchinson’s Massachusetts Regiment was taken the following day near King’s Bridge.[50] Pvt. Matthew Button of Preston was captured on September 23 at Montressor’s Island.[51]

Another belief associated with the Milford cartel is that some of the prisoners had been deliberately poisoned by the British. A county history from the late 1800s relates that prisoners from the Middletown area had been provided a “savoury soup” in New York just before they were released. Those who ate the soup “all died, either on the way home, or soon after arrival, evidently the result of some slow poison introduced with their food.”[52] According to this account, the victims included Pvt. Jesse Swaddle, who probably died aboard the ship, and Sgt. John Smith and Pvt. John Snow, who both died in Milford. Also mentioned were rangers Elisha Taylor and Seth Doane who perished soon after they reunited with their families in East Hampton. In his pension affidavit, Thomas Tryon described the case of “two lads by the name of Johnson” who he believed drank poisoned water.[53] The pair had both returned to Middletown where Stebbins Johnson died on January 12 and Prosper Johnson on April 4.[54] A confused account from the western part of Connecticut describes the sad fate of a soldier captured at Fort Washington named “Remembrance” who died on his way home after drinking poisoned water. The History of Torrington identifies him as Remembrance Sheldon, however, no man from Connecticut by that name was a prisoner in 1776. The story likely refers to Pvt. Remembrance Loomis of Captain Beebe’s Company who died on his way home.[55]

There were of course no autopsies or scientific analysis of the Glasgow men’s deaths. These kinds of post-mortem examinations are a fairly modern practice. All that was available in 1777 was supposition. But the heartfelt inferences of grieving people, no matter how sincerely held, do not constitute evidence of murder. It is clearly true that many of the malnourished former prisoners sent aboard the Glasgow died mysteriously within days, weeks, or months of their release. Survivors of the ordeal, as well as the anguished families and friends of those who perished, concluded these puzzling and fitful deaths could only have been caused by poison and the perpetrators had to be British. But an objective analysis reveals other suspects. Exposure, disease, exhaustion and despair may have played a part. Tragically, in some cases the toxin that finished the job may have been generous portions of otherwise healthy food lavished by those who loved the men most.

There is no surviving manifest with the names of each of the 225 or so Americans who were sent aboard the Glasgow. This makes it impossible to fully determine what became of all of them. From various contemporary accounts, we know that at least seventy men died on the ship or at Milford. My research shows dozens more died in early 1777 while returning along Connecticut’s country roads, or soon after they had arrived home.

There were also, fortunately, at least thirty-five of the Glasgow prisoners who survived past the spring of 1777. These include Thomas Tryon who eventually regained his health, was properly exchanged in 1779 and enlisted again as a fifer.[56] Ens. Joel Gillet of Harwinton lived until 1823, though his health never fully returned.[57] After he landed at Milford, Sgt. Theophilus Huntington of Bozrah lived another fifty-three years.[58] Fate caught up with Pvt. Ebenezer Keys in 1781. He accidentally drowned in Killingly.[59] Pvt. Joshua Wright of Cambridge, Massachusetts had been captured while serving with the ranger company at Fort Washington. He re-enlisted in 1778 and died in 1833.[60] Pvt. John Fletcher of Simsbury and Pvt. Peter Way of Lyme both lived to be seventy-three.[61] Oliver Woodruff was one of the longest-lived survivors. He wrote down his Revolutionary War experiences for his family when he turned eighty.[62] He died ten years later in Livonia, New York.

The Milford cartel was part of a general release of American prisoners by Gen. William Howe that continued into early 1777.[63] General Washington came to believe the British commander was cynically sending out dying men, hoping to receive healthy British prisoners in exchange.[64] An alternative explanation—at least for the Milford cartel—was that at the end of 1776, Howe sensed that victory was at hand. The Continental Army had suffered a season of devastating defeats in Brooklyn, at Kip’s Bay, and Fort Washington. Its remnants appeared to be a demoralized rabble that had ceased to be a serious threat. By making humanitarian gestures, Howe may have been trying to appeal to Americans who had become war-weary, to weaken their anti-British sentiment. By unilaterally paroling the prisoners in New York, Howe was restricting their ability to return to the battlefield while freeing himself from the burden of housing, feeding, and guarding them. Perhaps Howe did not want to kill off American civilians as much as he wanted to reclaim them as dutiful subjects of the king. But the cold weather, the disagreeable wind, and the variola virus conspired to ruin his scheme.

The Milford cartel was not only a tragedy for the prisoners who died and the people of Connecticut. By creating an angry citizenry thirsting for revenge, the enterprise was a disaster for General Howe.[65] Continuing into February 1777 more groups of Connecticut soldiers were paroled, but they would not be sent back by ship. They would go out of New York City on foot, across the King’s Bridge to the Bronx.[66]

Today, the story of the Glasgow cartel is still remembered by the people of Milford where a brownstone obelisk bears the names of those who died there, including that of their heroic Samaritan, Stephen Stow. Elsewhere in Connecticut, where the returning prisoners died separately and sometimes anonymously over a span of several weeks, the story is all but unknown. The memory of these soldiers’ sacrifice is preserved only in local or family histories, or on worn headstones in the state’s ancient burial grounds. But we should remember them all.

[1] Lieutenant Thomas Catlin “Deposition made on the 3d of May 1777,” quoted in Alain White, The History of the Town of Litchfield, Connecticut, 1720-1920 (Litchfield, CT: Enquirer Print, 1920), 78; Jabez Fitch, The New-York Diary of Lieutenant Jabez Fitch, ed. William H. W. Sabine (New York: The New York Times and Arno Press, 1971), 93.

[2] Connecticut Journal (New Haven), January 8, 1777, February 19, 1777; Journal of Oliver Babcock in Marcy Brown, Revolutionary War Pension Application, December 16, 1840, Pension Number W. 16,865, National Archives.

[3] Ethan Allen, A narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen’s captivity, Third Edition, (Burlington: H. Johnson & Co., 1838), 108; Ethan Allen to George Washington November 2, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0051; New York Gazette & Weekly Mercury, January 9, 1775; The Norwich Packet, June 15, 1778.

[4] Connecticut Journal, February 19, 1777.

[5] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[6] Journal of Oliver Babcock; Thomas Tryon, Revolutionary War Pension Application, August 25, 1839, Pension Number S. 32023, National Archives.

[7] Gary Brown, “Prisoner of War Parole: Ancient Concept, Modern Utility.” Military Law Review, Volume 156, no. 6 (June 1998): 211.

[8] Fitch, New-York Diary, 93.

[9] Ibid., 94.

[10] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[11] Affidavit of Daniel Babcock in Marcy Brown, Revolutionary War Pension Application, December 16, 1840, Pension Number W. 16,865, National Archives.

[12] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Tryon Pension Application.

[15] A Pay Roll of Capt. Jonathan Johnson’s Company in Col. Phillip B. Bradley’s Regiment of 30 June 1776 to date of discharge, US, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives; Middletown Part I A, Barbour Collection of Connecticut Vital Records, Connecticut State Library, accessed through Ancestry.com; Truscott C. Barnes, Barnes Family Yearbook, 1910 (Winsted, CT: Winsted Printing & Engraving Conn., 1910), 22.

[16] Catlin “Deposition.”

[17] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[18] Connecticut Journal, January 8, 1777

[19] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[20] Connecticut Journal, February 19, 1777.

[21] Oliver Woodruff, “Letter dated April 30, 1835,” quoted in Susan Woodruff Abbott, Woodruff Genealogy, Descendants of Matthew Woodruff of Farmington, Connecticut (New Haven, CT: The Harty Press, 1963), 77.

[22] Connecticut Journal, January 8, 1777.

[23] Tryon Pension Application.

[24] Woodruff, “Letter.”

[25] Martin A. Crook, “Refeeding Syndrome: Problems with Definition and Management.” Nutrition 30, no. 11-12 (2014): 1449.

[26] Federal Writers’ Project for The State of Connecticut; Milford Tercentenary Committee, History of Milford, Connecticut, 1639-1939 (Bridgeport: Press of Braunworth & Co., 1939), 63.

[27] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[28] Brian P. O’Malley, Brian P., “1776 – The Horror Show,” Journal of the American Revolution, January 29, 2019, allthingsliberty.com/2019/01/1776-the-horror-show/.

[29] Royal Ralph Hinman, A Historical Collection from Official Records, Files, &C., of the Part Sustained by Connecticut, During the War of the Revolution: With an Appendix, Containing Important Letters, Depositions, &C., Written During the War (Hartford, CT: Printed by E. Gleason, 1842), 115-116.

[30] Tryon Pension Application.

[31] Brown Pension Application.

[32] Federal Writers, Milford, 63.

[32] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[33] Joan J. Bidwell, Bidwell family history, 1587-1982 / compiled by Joan J. Bidwell v.1 (Baltimore, MD: Gateway Press, 1983), 28; Federal Writers, Milford, 63.

[34] Connecticut Journal, January 8, 1777.

[35] Joseph Olcott Goodwin, East Hartford: Its History and Traditions (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood & Brainerd Co., 1879), 118.

[36] Allyn S. Kellogg, Memorials of Elder John White, One of the First Settlers of Hartford, Conn., and of His Descendants (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood and Company, 1860), 108.

[37] Charles R. Hale, Hale Collection of Connecticut Cemetery Inscriptions, vol. 13 (Hartford, CT: Connecticut State Library, 1937), 280.

[38] Entry for Aaron Drake, January 1777, “Connecticut, Charles R. Hale Collection, Vital Records, 1640-1955,” FamilySearch www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2658554.

[39] Tolland Vital Records 1715-1850, Barbour Collection of Connecticut Vital Records, Connecticut State Library, accessed through Ancestry; Elisha Benton gravestone, South Yard Cemetery, Tolland, Connecticut, FindaGrave.com.

[40] Tony J. Norris, “For a Change of Pace, Go East,” Hartford Courant, May 13, 1983, D10.

[41] Barbour Collection of Connecticut Vital Records, Connecticut State Library, accessed through Ancestry.com.

[42] Tryon Pension Application; Loren Pinckney Waldo, The Early History of Tolland (Hartford, CT: Press of Case, Lockwood & Co., 1861), 79.

[43] Elijah Stanton, Revolutionary War Pension Application, June 7, 1832, Pension Number S. 14,623, National Archives.

[44] James Watson Webb, Reminiscences of Gen’l Samuel B. Webb of the Revolutionary Army (New York: Globe Stationery and Printing Co.), 31.

[45] Journal of Oliver Babcock.

[46] Allen to Washington, November 2, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0051.

[47] Allen, Narrative, 88.

[48] Payne Kenyon Kilbourne, Sketches and chronicles of the Town of Litchfield, Connecticut: Historical, Biographical, and Statistical: Together with a Complete Official Register of the Town (Hartford, CT: Press of Case, Lockwood and Company, 1859), 99-100.

[49] Fitch, New-York Diary, 149.

[50] David Hendrix, Revolutionary War Pension Application, July 27, 1818, Pension Number S. 37098, National Archives; Connecticut Journal, February 19, 1777; Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War. A Compilation from the Archives, vol. 8 (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., State Printers, 1901), 111.

[51] Peter Force, ed., American Archives – Fifth Series, vol. 3 (Washington: Clarke & Force, 1837-1846), 717; Hinman, A Historical Collection, 317.

[52] Henry B. Whittemore, History of Middlesex County, Connecticut: With Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men (New York: J. B. Beers & Co., 1884), 401.

[53] Tryon Pension Application.

[54] Stebbins Johnson, gravestone, Old Farm Hill Cemetery, Middletown, Connecticut, digital image s.v. “Stebbins Johnson,” FindaGrave.com; Prosper Johnson, gravestone, Old Farm Hill Cemetery, Middletown, Connecticut, digital image s.v. “Prosper Johnson,” FindaGrave.com.

[55] Samuel Orcutt, History of Torrington, Connecticut, From Its First Settlement in 1737, with Biographies and Genealogies (Albany: J. Munsell, printer, 1878), 225; Kilbourne, Sketches, 101.

[56] Tryon Pension Application.

[57] Joel Gillet, Revolutionary War Pension Application, May 6, 1818, Pension Number S. 36540, National Archives.

[58] The Pension Roll of 1835 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1992.

[59] James Newell Arnold, Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636–1850 (Providence, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Company, 1891–1912).

[60] Joshua Wright, Revolutionary War Pension Application, June 1, 1820, Pension Number W. 19660, National Archives.

[61] Connecticut Courant (Hartford), September 7, 1813; Lucy Way, Revolutionary War Pension Application, June 7, 1838, Pension Number W. 18228, National Archives.

[62] Abbott, Woodruff Genealogy, 77; Oliver Woodruff, Revolutionary War Pension Application, September 27, 1832, Pension Number S. 14885, National Archives.

[63] O’Malley, “1776 – The Horror Show.”

[64] Washington to William Howe, April 9, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0103.

[65] Richard Buel, Jr., Dear Liberty: Connecticut’s Mobilization for the Revolutionary War, (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press), 154.

[66] William Slade, Diary of William Slade, New Canaan, Conn., Later of Cornwall, VT, quoted in Danske Dandridge, American Prisoners of the Revolution (Charlottesville, VA: The Michie Company, 1911), 499, 500-501; Ichabod Perry, Reminiscences of the Revolution (Lima, NY: published by Ska-Hase-Ga-O Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, 1915), 17.

10 Comments

Thanks for a beautifully researched and written article. I have been frustrated by all the mythology about this event and you have provided an excellent analysis. Thank you.

Thank you, Selden.

Well written and researched. Thanks!

Thank you, Margaret.

Selden and Margaret, thank you both for your comments. I appreciate the feedback!

Tom, thank you for such a well written and researched article. I am the City Clerk of Milford and as the 250th anniversary approaches.

I will be reaching out to the city and town officials of the home towns of the POW’s with the expressed goal of “remembering them all.” The research you have done will make this job easier.

Thank you for publishing such a detailed account.

You are welcome, Peter. Let me know if I can be of assistance. Tom

Mr. Hogan – Your article is astounding! Growing up in Milford I learned the story of Stephen Stow and as an adult I have docented at his house countless times but I have never known the full story until your article. Thank you.

Thank you, Mr. Stowe. I appreciate your hospitality when I visited the hose and cemetery last year. Tom

Peter and Arthur – Thank you for your thoughts. My compliments to your community which has never forgotten those who sacrificed during the Revolution.