On April 7, 1776 American ships began dropping anchors off New London, Connecticut. Esek Hopkins, commander in chief of the new Continental navy, was returning from a successful raid on the town of New Providence on Nassau island in the Bahamas. While there, the Americans had seized eighty-eight desperately needed cannon and fifteen mortars, thousands of roundshot, other artillery implements and some gunpowder, though much of the last item had been spirited away by the island’s inhabitants.[1] It should have been the highlight of Hopkins’ Revolutionary War career. Instead, the raid proved controversial and marked the beginning of his downfall. At issue was the nature of the orders Congress had given Hopkins before the raid, his execution of them, and his interpretation of his own authority.

On January 5, 1776 the Naval Committee of the Continental Congress ordered Hopkins to take the Continental navy to the Chesapeake Bay, where Virginia’s governor had gathered a motley collection of small craft and Royal Navy vessels. Unless outmatched by the enemy there, Hopkins, who had the title commodore as the senior captain, was to enter the bay and sweep it of hostile vessels. Next, he was to perform the same mission on the Carolina coasts. After that, the American flotilla was to proceed to Rhode Island and “attack, take and destroy all the Enemies Naval force that you may find there.”[2] The committee’s orders were direct. The tasks were not a menu of options or recommendations, but a sequence of operations he was to undertake. The committee had a clear strategic purpose in mind: to clear the east coast of enemy naval forces, beginning in Virginia. It was an ambitious, and perhaps unrealistic, set of orders.

As if to emphasize its commitment to clearing the coasts, the committee and its members took additional steps and committed resources to coordinating with Hopkins on his coastal sweep. The committee informed the Virginia Convention the same day that it was aware of “the peculiar distress that the Colony of Virginia is liable to from a Marine enemy” and that Congress had assembled and fitted out an expedition to the Chesapeake Bay to “seize and destroy as many of the Enemies ships and Vessels as they can.” Moreover, it requested the convention to collect information about British naval dispositions and two hundred riflemen to rendezvous with a ship of the American fleet at Cape Henry, pass the information on to Hopkins, and possibly augment American seamen for operations in the bay.[3] Similarly, it ordered Cap. William Stone of the sloop Hornet to take his ship and the schooner Wasp from Baltimore and down the Chesapeake Bay, annoy the enemy there, and then rendezvous with Hopkins after joining them.[4] (Both ships eventually joined Hopkins in the Delaware Bay.)

Later in January, Christopher Gadsden, a committee member from South Carolina, wrote to Hopkins, “sooner or later I flatter myself we shall have your Assistance at Carolina where you may depend on an easy Conquest, to at least be able to know without Loss of Time when off the Bar the Strength of the Enemy.”[5] Just over a week later, on January 18, the committee was even more optimistic. It updated Hopkins with the news that the few British ships on the Carolina coasts had departed, likely for Savannah, with two Royal governors. Recognizing that the British vessels were inferior to the American flotilla, the committee suggested that Hopkins might be able to capture the ships and governors by proceeding to Georgia.[6]

The committee’s orders also provided Hopkins with an escape clause of sorts. This last, brief portion of Hopkins’ orders would prove his undoing:

Notwithstanding these particular Orders, which ‘tis hoped you will be able to execute, if bad Winds, or Stormy Weather, or any other unforeseen accident or disaster disable you so to do You are then to follow such Courses as your best Judgment shall Suggest to you as most useful to the American Cause and to distress the Enemy by all means in your power[7]

Whereas the committee’s orders to clear the coast were explicit, Hopkins’ latitude to act freely was conditional. He did not have to proceed with the Virginia mission if intelligence indicated the British were there in significantly superior force and he could pursue another course of action if weather or some unforeseen accident or disaster made clearing the coast impossible. Four members of the seven-man committee signed the orders: Hopkins’ brother, Stephen of Rhode Island, Silas Deane of Connecticut, Christopher Gadsden, and Joseph Hewes of North Carolina.

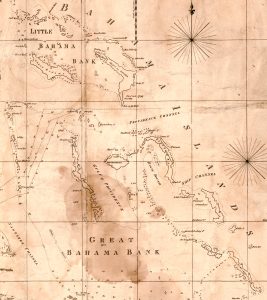

The navy flotilla spent the better part of the next six weeks stuck in the Delaware River and Bay, trapped by ice, unfavorable winds, and a shortage of men. As the senior captain—and because the navy had no rank higher than captain—Hopkins became the operational commodore in addition to his position as commander-in-chief. There is evidence that he already had the Bahamas in mind. On February 14, as he prepared to depart, Hopkins ordered Capt. Nicholas Biddle of the Andrew Doria to keep company with him and, if separated, “use all Possible Means to join the Fleet as soon as possible.” But more importantly, if Biddle was separated and unable to rejoin shortly, he was to “make the best of your way to the Southern part of Abacco one of the Bahama Islands, and there wait for the Fleet fourteen days.”[8] Indeed, Abaco island proved to be the fleet’s next destination. Once in the Bahamas the navy seized two local vessels whose captains informed Hopkins of a large store of gunpowder in Nassau on New Providence island. Consequently, the fleet made that its target, rather than the Virginia capes or the Carolina coast.[9] The Americans captured New Providence in a coup de main on March 3 and occupied the town for two weeks before departing on March 17. The fleet returned to American waters and fought an inconclusive battle with the Royal Navy frigate Glasgow before settling in at the New London anchorage.

Despite Hopkins’ capture of artillery, which largely remained in New England, Congress questioned his execution of his orders. Dissatisfaction in the south was particularly acute. During May, Congress shifted responsibility among a number of committees “to enquire how far Commodore Hopkins has complied with the said instructions, and if, upon enquiry, they shall find he has departed therefrom, to examine in to the occasion thereof,” which included calling witnesses and examining papers.[10] The issue eventually landed with the Marine Committee in July. It filed a report on August 2, which was set aside to be taken up by the whole Congress at a later date.[11] Hopkins requested a hearing and sat before the Marine Committee on Monday, August 12. He responded to the committee’s initial findings and requested that two witnesses appear on his behalf. After some discussion, the committee dismissed Hopkins and the whole body started its debate.[12]

The committee did not keep a transcript of its interviews, but Hopkins’ defense of his command can be reconstructed from his report to Congress and in a memo Thomas Jefferson drafted after the August 12 hearing. In his report, Hopkins noted that many of his crewmen were ill, some with smallpox, and he did not think the fleet could remain in colder waters. That was the reason he selected the rendezvous in the Bahamas. He also lost contact with the small ships Hornet and Fly after leaving the Delaware Bay, which may have made him less confident in his intelligence gathering capabilities, although he did not mention it in the report.[13] According to Jefferson, the commodore elaborated that had not gone to Virginia because he believed British naval forces there outmatched him, especially with so many American seamen down due to illness. He did not visit the Carolina coasts because he believed enemy forces in both places had gone to Georgia, where they also were superior to his own flotilla. Hopkins chose Abaco as a rendezvous site because it was closer to Georgia than the Carolinas. While at Abaco, he learned that powder was stored in New Providence, so he proceeded there with the intention of seizing it. He returned to New England because he still believed British forces in Savannah outmatched him and that Rhode Island needed his seized cannon more than the Carolinas. Moreover, he was more confident in safely reaching New England. Curiously, Hopkins then decided not to depart Rhode Island for the Carolinas because his orders directed him to Rhode Island. Importantly, Hopkins viewed the “escape clause” in his orders less conditionally; his judgment about the public good was sufficient to depart from his directed coastal sweeps of Virginia and the Carolinas. According to Jefferson, Hopkins summed up the challenge of balancing a centralized strategy against a commander’s discretion, or at least his reading of it: “Instructions are never given positively and it is right they should not be, because of change of circumstances.”[14] Whether Congress and its committees saw things in the same light was another question.

Jefferson rejected Hopkins’ arguments, concluding that the commodore’s decision to forego his southern missions and proceed directly to the Bahamas was premeditated. As evidence, he pointed to the facts that Hopkins had not actively sought intelligence in the Chesapeake or Carolinas, but was instead satisfied to accept hearsay. In particular, he questioned Hopkins’ decision to pass South Carolina by. After all, Gadsden had made some arrangements for the commodore to get a pilot and receive intelligence. For Jefferson, Hopkins’ decision to forego the Carolina portions of his mission was inexcusable, “that being not only the main object of his expedition, but in truth the object of equipping the navy.” Jefferson went on to dissect every point Hopkins made regarding his technical difficulties, but more importantly offered his own view on the limits of Hopkins’ discretion regarding his orders: “True all instructions have [a] discretionary clause. This proves they have some positive intention, otherwise there was never a positive instruction and never a disobedience of orders, which is not true.” In other words, if a commander’s freedom to act always trumped the purposes for which he had been given command, then positive orders were meaningless. Jefferson concluded that Hopkins never intended to obey his.

John Adams did not see things the same way. He was satisfied with much of Hopkins’ defense and found it, in the main, sufficient to excuse the commodore’s actions. Instead, he detected a distinct note of regionalism and an “anti New England Spirit.”[15] Jefferson’s indictment, and Adams’ defense, of Hopkins have the air of lawyerly arguments, more suited to a courtroom than the deck of a ship. Unfortunately, neither they nor Hopkins—as explained by Jefferson—made a strategic argument for either following or disregarding his orders. At a minimum, Hopkins and Adams failed to appreciate the depth of southern concerns about Britain’s naval activities on the coasts there.

On August 15, Congress resumed debate over the committee’s report on Commodore Hopkins and his adherence to orders. It resolved that “Commodore Hopkins, during his cruise to the southward, did not pay due regard to the tenor of instructions, whereby he was expressly directed to annoy the enemy’s ships upon the coasts of the southern states; and, that his reasons for not going from Providence immediately to the Carolinas, are by no means satisfactory.”[16] Adams recorded the vote as six colonies in favor of the resolution, three opposed, and three divided.[17] The Congress did not necessarily fault Hopkins for going to the Bahamas, but for not proceeding from there to the Carolina coast. Clearly, the coastal sweeps ordered on January 5 remained foremost in mind.

The censure was not enough to remove Hopkins from command, but it marked the beginning of his downfall. Southern dissatisfaction with the New Providence raid was only exacerbated by the dispensation of the artillery Hopkins seized, which did not make its way south. Disagreements between himself and George Washington over troops the general had loaned the commodore were elevated to Congress. Similarly, Hopkins and his captains regularly argued amongst themselves and the complaints of seamen made their way to Congress. To compound the problem, personnel shortfalls, equipment inadequacies, and the growing strength of the Royal Navy in American waters made major American fleet operations next to impossible for the rest of the year, something the Continental Congress did not always appreciate. In his profile of the commodore, historian William Fowler, Jr. described him “as an ordinary man who had the misfortune to live in extraordinary times.”[18] Hopkins was finally dismissed from the service at the beginning of 1778.

[1] Nathan Miller, Sea of Glory: A Naval History of the American Revolution (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press), 1974, 111; “Commodore Esek Hopkins to Governor Jonathan Trumbull, April 8th 1776,” William Bell Clark, ed. Naval Documents of The American Revolution (Washington, DC: The U.S. Navy Department, 1962 – ), 711-712 (NDAR).

[2] “Naval Committee to Commodore Esek Hopkins, January 5, 1776,” NDAR, 3:637-638.

[3] “Naval Committee to the Virginia Convention, January 5, 1776,” NDAR, 3:640.

[4] “Naval Committee to Captain William Stone, January 5, 1776,” NDAR, 3:640. Both ships were later ordered to convoy American vessels out of the Chesapeake and then rendezvous with Hopkins at the Delaware capes. “Journal of the Continental Congress, January 9, 1776,” NDAR, 3:692; “Naval Committee to Captain William Stone, 10th January 1776,” NDAR, 3:719).

[5] “Christopher Gadsden to Commodore Esek Hopkins, 10th Janry 1776,” NDAR, 3:720.

[6] “Continental Naval Committee to Commodore Esek Hopkins, January 18, 1776,” NDAR, 3:847.

[7] “Naval Committee to Commodore Esek Hopkins, January 5, 1776,” NDAR, 3:638.

[8] “Commodore Esek Hopkins to Captain Nicholas Biddle, Febry 14th, 1776,” NDAR, 3:1291.

[9] “Journal Prepared for the King of France by John Paul Jones,” NDAR, 4:133.

[10] “May 22, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 4:375 (JCC). Naval Documents of the American Revolution generally refers to the committee as the “Naval Committee” and Journals of the Continental Congress as the “Marine Committee.” Both names are used here to be true to the source material.

[11] “August 2, 1776,” JCC, 5:628.

[12] “August 2, 1776,” JCC, 5:648.

[13] “To the honble. John Hancock Esqr, April 8th 1776,” Alverda S. Beck, ed., The Letter Book of Esek Hopkins (Providence, RI: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1932), 46-47.

[14] “Jefferson’s Outline of Argument Concerning Insubordination of Esek Hopkins, 12 August 1776,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-15-02-0547.

[15] “Monday August 12, 1776, from the Diary of John Adams,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0166.

[16] “August 15, 1776,” JCC, 5:659.

[17] John Adams to Samuel Adams, August 18, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0217.

[18] William M. Fowler, Jr, “Esek Hopkins: Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Navy,” in James C. Bradford, ed., Command Under Sail: Makers of the American Naval Tradition, 1775-1850 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 15.

4 Comments

I’m sorry, but I have to disagree strongly with the thrust of this article. Because Congress was terrified that they had already given Washington too much power on land, they limited Hopkins at sea by prohibiting him from taking any action without first obtaining a vote of his captains. The captains vetoed Rhode Island when they learned that the British Naval force there had been greatly enlarged; they vetoed the Chesapeake when they learned that a strong British Naval force had arrived there; they vetoed Charleston because no accurate charts of the dangerous approaches could be found. That left Nassau. There isn’t room here to say all that should be said.

Thanks for the comment. Love to hear more detail about your evidence so I can check it out. I always thought it odd that Congress censured Hopkins for what looked to be a successful mission, which is what prompted me to look into the issue. The January 8 orders were probably unrealistic so the decision making you describe is pretty logical. But, it doesn’t seem to track with the interaction between Hopkins and the Congress leading up to his censure. At a minimum, there was not a strategic meeting of minds before the Naval Committee issued Hopkins’ orders on January 8.

In his letter reports to John Hancock and Nicholas Cooke on April 8th, Hopkins didn’t offer any of those reasons. Hopkins indicated he “formed an Expedition against New Providence” at Abaco in the Bahamas when Hornet and Fly didn’t make the rendezvous there. Similarly, John Paul Jones described the decision to attack New Providence as an opportunistic one made in Bahamian waters after the fleet learned about gunpowder stored there. (Both sources are cited in the article in notes 9 and 13).

If the captains had vetoed Hopkins discretion, as you argue, I also would have expected him to rely on them in explaining his decision to Congress, but he only called two witnesses. (JCC, V, 648, note 12 in the article). Jefferson’s summary of Hopkins’ in-person defense, which likely reflected the former’s southern biases, does note that Hopkins claimed to have received intelligence about one ship joining Dunmore at the Virginia Capes. But, according to Jefferson, Hopkins declined to go to the Carolinas because the British vessels there had gone to Georgia. This may be a reference to the January 18 letter from the Naval Committee to Hopkins, informing him of that case. But, the committee clearly expected him to follow the British to Georgia since his mission was essentially to destroy British vessels plaguing the Carolina coasts.

As for Rhode Island, that was to occur third under his January 8 orders. Hopkins’ choice of a rendezvous point at Block Island left the option to proceed there open to him. He explained his rationale for not pursuing the Glasgow into RI waters, where he would have encountered a substantial British squadron, as the result of 30 of his “best Seamen” being aboard prize ships and some of the crew on board his vessels as being drunk. So, to secure the prizes he had already taken he “thought it most prudent” to end the chase of the Glasgow and proceed to Connecticut. No doubt the poor performance of his flotilla and the damage taken in the Glasgow fight weighed on his mind.

In any event, the point of the article was to explain Congressional reasoning for censuring Hopkins, not to pass judgment on Hopkins’ decision-making or the reasonableness of the Congressional thought process. As I mentioned in the piece, Jefferson and Adams seem to think more like lawyers than a commander in the field. All that said, Hopkins didn’t make the arguments you offered in his letters to Congress, the governor, or in his examination by Congress (if Jefferson is accurate in his recording of the latter). If Congress had constrained Hopkins by the votes of his captains and they had indeed voted that way, then we need a better explanation for Hopkins offering up other reasons for his command decisions and why Congress censured him at all.

Hello Mr. Sterner, do you have an email I could reach you at about some of your work, and some of my studies? If you do not want to publish it here perhaps we can find another way off line from here? I could post my own here if you prefer? I was not sure if it would be blocked or censored if I posted it, not sure of the rules here, but just wanted to reach out and let you know I have enjoyed your work, particularly on events during 1782 and I would like to speak with you more about it if possible.

Thank you sir!

You can send messages to a JAR author to the editors address (see the About > Contact link); they will be forwarded to the author.