John Marshall’s life (1755-1835) has been the subject of many authors over the nearly 190 years since his death. Albert Beveridge, Charles Hobson, and Leonard Baker immediately come to mind. There are others, of course; and there are those works which look at the life of Marshall’s wife, Mary (Polly). Their home of nearly fifty years in Richmond, Virginia, is a much-visited site and continues to reach new audiences with innovative programming. Marshall’s published papers (Chapel Hill, 1973-1993) cover twelve volumes (a more manageable one-volume edition was published by the Library of America in 2010). This is to say that John Marshall is not one of the cadre of forgotten American Founders.

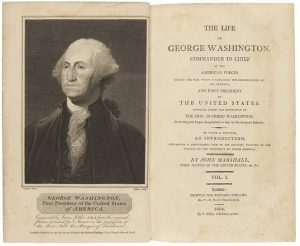

His contributions to the American story generally involve his work on the Supreme Court as Chief Justice from 1801 to 1835. Other aspects of his life, soldier, student, private attorney, and his work in France during the XYZ Affair are a close runner up in his story. Yet, another contribution to the American story, which commenced around the same time as his Supreme Court work, is his work in the development of the American history narrative biography; in particular, his landmark book The Life of George Washington. This aspect of Marshall’s life is vastly overshadowed by his Supreme Court career. While his Supreme Court career was precedent-setting, his publishing career was no less so, and indeed could be said to have ultimately led to the innumerable books and journals, print and electronic, which thrive to this day inspired by Marshall’s commitment to primary sources.

After the death of George Washington in December 1799, his nephew Bushrod Washington, a justice on the United States Supreme Court, began to consider a fitting tribute to his late uncle. A biography was the preferred choice, but who would write it? One of Washington’s secretaries, Tobias Lear, was considered, as was Bushrod himself. Martha Washington was also thought to support the idea of a biography to ensure the posthumous remembrance of her husband and was thought to support John Marshall as its author. In the year following his uncle’s death though, Bushrod was the prime mover of the idea.[1] Bushrod had inherited his uncle’s vast trove of papers along with the Mount Vernon estate itself, so, he had access to one of the most enviable sources of primary documentation available. After Lear was removed from consideration, Bushrod and Marshall were the two remaining viable options. Bushrod was already finishing up a publication project of his own, the Virginia State Court Reports, and suffered from eye problems, making prolonged research and writing difficult on top of his judicial duties.

In 1800, following an abbreviated term in the House of Representatives, John Marshall was appointed secretary of state by President John Adams. In the year following Washington’s death, the nation was struggling with growing pains, some self-inflicted, some as the result of the forces roiling Europe whose echoes reached America. President Adams had a disastrous year in 1800 and as secretary of state Marshall could do little but observe events as they unfolded at home and abroad. One of the domestic events impacting the president involved the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth resigned due to ill health. Adams nominated former Chief Justice John Jay, who declined. In the new year of 1801, Adams’ luck changed slightly (even after having been defeated by Thomas Jefferson in the election of 1800) when, feeling frustrated at every turn, he nominated Marshall as chief justice almost as an afterthought. Both men were together in an office working, and Adams wondered aloud whom he could nominate as chief since Jay had declined. Looking up at Marshall, he made the snap decision to put forth Marshall’s name, a move Adams would later look back upon with pride, writing to Marshall in 1825, “And it is the pride of my life that I have given to this nation a Chief Justice equal to Coke or Hale, Holt or Mansfield.”[2] Adams’ invoking the great English jurists was indeed an honor for Marshall.

When appointed, Marshall was simultaneously beginning to feel the pressure from his friend and fellow Justice Bushrod Washington to seriously consider the authorship of the proposed George Washington biography. In fact, Marshall had already caught the attention of publisher Caleb Wayne, who was corresponding with Bushrod. Wayne wrote to ask Marshall about being an author and about his access to George Washington’s papers. Marshall replied, “I receivd while in Virginia your letter of the 3d. inst. which I have forwarded to Mr. Washington. Shoud he write to me on the subject you shall immediately receive any communication he may make.”[3]

Marshall was also feeling pressure from financial concerns in his life. At the time he became chief justice, he was in debt by nearly $30,000, an enormous sum. He had speculated wildly in western lands and had been neglecting his law practice in recent years of service to President Adams. Therefore, the prospect of authorship, which could produce significant income quickly, appealed to Marshall. The reward for the project was premised on “tens of thousands of prosperous Federalists who could be depended upon to purchase at a generous price a definitive biography of George Washington.”[4]

Marshall, Bushrod, and their publisher Wayne would soon learn a hard lesson: relying on newly-formed party affiliations to base a business model for publishing was a bad idea. According to one biographer, “Marshall and Bushrod made extravagant estimates of the prospective sales of the biography and the money they would receive.”[5] The project was destined to have an overall Federalist feel, as Wayne was a noted Federalist partisan and editor of the Federalist newspaper Gazette of the United States. This virtually ensured the eventual publication would be tarnished by partisan innuendo. Marshall was so concerned about this that he did not allow his name to appear on in the final contract for the work, dated September 22, 1802, between Marshall, Bushrod, and Wayne, for fear of tipping off his cousin and arch political rival President Thomas Jefferson. Unbeknownst to Marshall, Wayne had reached out to Jefferson just five days previously, on September 17, 1802, asking for Jefferson’s support. He wrote, “Enclosed you will receive Proposals for publishing by Subscription, a History of the late General George Washington; your presenting it to any of your friends, will greatly oblige me, and should you think proper to sanction it with your own name, it will be duly appreciated.[6]

It did not take long for Jefferson to learn of the principals behind the project. He immediately thought it a ploy to influence the 1804 election, two years away. So incensed was Jefferson over the whole project that he spent the next twenty-two years of his life trying to recruit an author from his party to write a counter-biography—to no avail. Ironically, Jefferson was one of the first to subscribe to Marshall’s undertaking.[7] Nonetheless, by now a hyper-partisan, Jefferson did what he could to thwart sales, with some effect. “Jefferson’s attacks on the yet unwritten work caused most of the Republican postmasters to refuse to accept subscriptions” for the biography.[8]

John Marshall began the project with access to the greatest collection of primary sources then in existence: the papers of George Washington stored at Mount Vernon under the control of Bushrod Washington. Over the course of the project, Marshall would borrow thousands of letters and remove them to his home in Richmond for research. Marshall also started to collect firsthand accounts of Washington from those who worked with him during his long career. Marshall sent “letters to [Washington’s] friends from Revolutionary War days and of the postwar period asking them for additional information about specific events and for their general reminisces of Washington.”[9]

Marshall’s tenure as chief justice got off to a much better start than his role as biographer. While his historical methods would fit into any history lecture hall today (use of primary sources and reaching out to those who worked with Washington), Marshall found the process of starting the project challenging. His “day job” as chief justice was proving nearly overwhelming; added to this was the increasing pressure of the proposed biography. By 1803, a year after the contract was signed, subscribers to the proposed set were barely at 10 percent of those anticipated (30,000 were hoped for, barely 4,000 had subscribed by the end of 1803). In fact, even Marshall’s planned physical estimates of the proposed biography, “4 or 5 volumes in octavos of from 4 to 500 pages each,” was proving unrealistic due to the projected costs of production of the books versus the less than robust subscription base.[10]

Marshall, “somewhat tone deaf overall to Wayne’s business concerns, could only write how he had decided to solidify and streamline his approach to the process of editing his work in preparation for publication.”[11] Marshall wanted a work that was worthy of Washington. While Wayne did not disagree, he was still a businessman and profits and expenses had to be considered. The process of producing a set of books in the early nineteenth century did not favor a five-volume set totaling over 2,000 pages. Not only would they be unwieldly, but these volumes also needed to be filled with information based on original sources that most would have found unimaginably boring. More to the liking and the budget of the “average” American was Mason Weems, whose mostly fictional “biography” of Washington was being produced at the same time. (Weems also served as a subscription salesman for Marshall’s biography.)

Marshall’s first volume dealt mostly with colonial American history with no notice of George Washington. Subscribers had already started to demand their money back even before the first volume appeared due to delays, and the topic of volume one only increased those calls for refunds. Additionally, political tumult was impacting sales. Marshall and Wayne were forced to readjust their schedules several times by mid-1804 when volume 2 appeared. Still, “Not one sale beyond the subscribers occurred” during the first year or two and at best the publisher Wayne broke even.[12]

Worked dragged on for Marshall and Bushrod and by 1804 errors in their volumes were being caught by many readers. By June 1 Marshall was horrified at the number of errors. Citing the pressing needs of his day job, he wrote to Wayne:

During the pressure of my official business I have been able to give the sheets composing the first volume only a hasty reading. I inclose you a paper containing corrections—principally of errors in pointing. I wish it may be possible to make them before the first volume shall be published—but I fear this cannot be done. I have not had time to read the notes. Before any second edition I shall be glad to have the enclosed returned to me that I may at more leisure make more alterations.[13]

Furthermore, Marshall was having difficulty in determining quotation use (he had taken to quoting pages at a time from other works), references, and other components of authorship. Marshall wrote to Wayne on January 22, 1804:

Previous to the receipt of your letter of the 10th I had answerd all the enquiries which had before been made respecting the work in which we are engaged. I am a good deal puzzled to decide what is to be done respecting the authorities quoted. There was some difficulty in fixing the references because several pages successively are substantially taken from the same books & it was my idea that the whole shoud be considerd as referd to by placing the names of the authors at the foot of the pages. I cannot now correct it as I have not the manuscript, & can only advise that the mark of reference be placed at the end of some paragraph, as your judgement shall direct, on each page at the foot of which you find the names of the authors written. It will probably be generally right to place the letter of reference at the close of the last paragraph.

As the volume still continues too large, it is most advisable to reduce it by omitting such notes as your own judgement & that of any friend you may consult, shall dictate. I have mentiond that respecting the controversy in Massachussetts concerning a fixd salary & the ro[y]al proclamation issued after the conclusion of the war. I am desirous that you shoud select such others as you think may be parted with, so as to bring the book within a reasonable compass.[14]

In total, Marshall wrote some fifty-plus letters to Wayne during their partnership. He received as many.

Despite the problems encountered by Marshall, Bushrod, and Wayne, the research, writing, and publishing proceeded. Working through the machinations of President Jefferson, the popularity of the competing Mason Weems biography, the continued collapse of the Federalist party which Marshall in part depended on for sales, and of course, Marshall’s day job as chief justice (he authored some seventy-five opinions during the years of research and writing), the set was ultimately completed. By the fall of 1807, the final volume was published. Marshall and Wayne would continue to adapt the set with new editions featuring some or all the volumes over the rest of Marshall’s life.

Today, first editions of Marshall’s Washington are considered collectables. His one-volume edition, which was created a few years after his death, is still available in a modern edition through the Liberty Fund publishers. And while the academic discipline of history has become professionalized since Marshall’s days, his reliance on primary materials is still a standard of historical research and writing.

[1]Lawrence B. Custer, “Bushrod Washington and John Marshall: A Preliminary Inquiry.” American Journal of Legal History 4, no. 1 (January 1960), 43n42.

[2]John Adams to Chief Justice Marshall, August 17, 1825, Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[3]The Papers of John Marshall Digital Edition, rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/JNML-01-04-02-0340.

[4]Jude M. Pfister, America Writes its History, 1650-1850, the Formation of a National Narrative (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014), 109.

[5]Albert J. Beveridge, The Life of John Marshall, vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919), 224.

[6]Caleb P. Wayne to Thomas Jefferson, September 17, 1802,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-38-02-0360.

[7]Beveridge, The Life of John Marshall, 235.

[8]David Leslie Annis, “Mr. Bushrod Washington, Supreme Court Justice on the Marshall Court” (PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 1974), 109.

[9]Leonard Baker, John Marshall: A Life in Law(New York: Macmillan, 1974), 438.

[10]Bushrod Washington to Caleb Wayne, in Beveridge, The Life of John Marshall, 235.

[11]Pfister, America Writes its History, 111.

[13]The Papers of John Marshall Digital Edition, rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/JNML-01-06-02-0167.

[14]The Papers of John Marshall Digital Edition, rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/JNML-01-06-02-0147.

Recent Articles

Dr. John L. Linn’s Service with Two Armies and a Navy

The American Revolution Comes to Georgia: The Battle of the Riceboats, 1776

Being Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History

Recent Comments

"The American Revolution Comes..."

Excellent article. Thank you for correcting the narratives I had learned.

"The Discovery of an..."

While searching for ancestors who served in the Revolutionary war I happened...

"The Deadliest Seconds of..."

The Randolph blew up taking with it the flower of Philadelphia youth....