For many years Paul Revere was not prominent in the history of the Revolutionary War. Extremely versatile, he was a Massachusetts militia officer and artillery commander, a skilled artist and engraver, a caster of bells, an esteemed silversmith, and an industrialized coppersmith.[1] He also was a prosthodontist and at one point a forensic dentist.[2] Revere was the principal messenger of the patriot leaders, carrying messages to patriots in New York and Philadelphia on several occasions. Later, he wrote three accounts of his ride to Lexington. Despite these firsthand accounts, Revere did not appear prominently in histories that dealt in the period until after his death in 1818. After the fiftieth anniversary of the April 19 event he began to acquire notoriety largely through Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,” published in Tales of a Wayside Inn in 1863.

Although multitalented, reportage and handwriting were not among Revere’s strengths. He made two undated depositions that contain his version of his messenger ride on April 19. He subsequently witnessed the renowned battle on Lexington Green from “a house at the bottom of the street,” one that largely blocked his view of the militia. The rambling depositions had been thought not worthy of including with those of other witnesses in the history of the event prepared by Congress. Revere prepared a third account some years after the other two. Also not dated, this account was penned at the request by Jeremy Belknap, the then corresponding secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Revere’s text, edited by Belknap in 1798, did not differ materially from the earlier versions, but for the first time Revere focused upon the activities of Doctor Benjamin Church.[3]

As I have mentioned Dr. Church, perhaps it might not be disagreeable to mention some Matters of my own knowledge, respecting Him. He appeared to be a high son of liberty. He frequented all places where they met, Was encouraged by all the leaders of the Sons of Liberty, and it appeared he was respected by them, though I knew that Dr. [Joseph] Warren, had not the greatest affection for him. He was esteemed as a very capable writer, especially in verse: and as the Whig party needed every Strenght, they feared, as well as quoted him. But it was known that the Sons of Liberty Songs, which we composed, were parodized by him, in favor of the British, yet none dare charge him with it. I was a constant and critical observer of him, and I must say, that I never thought Him a man of Principle; And I doubted much in my own mind, whether He was a real Whig. I knew that He kept company with a Capt. Price, a half-pay British officer, and that He frequently dined with him and Robinson, one of the commissioners. I know that one of his intimate acquaintances asked him why he so often was with Robinson and Price? His answer was He kept company with them for the purpose of finding out their plans. The day after the Battle of Lexington, I met him in Cambridge, when He shew me some blood on his stocking, which he said spurted on him from a Man who was killed near him, and that he was urging the Militia on. I well remember that I argued with myself if a Man will risque his life in A Cause, he must be a Friend to that cause; and I never suspected him after, till he was charged with being a Traytor.

Revere’s account also related an incident that involved Dr. Warren.

“Church told Warren: I am determined to go to Boston tomorrow—Dr. Warren replied, are you serious Dr. Church? They will hang you if they catch you in Boston. He replied, I am serious and I am determined to go at all adventures. After considerable conversation, Dr. Warren said if you are determined, let us make some business for you. They agreed that he should go to get medicine for their and our Wounded officers. He went the next morning; and I think he came back on Sunday evening. After he had told the Committee how things were, I took him aside, and inquired particularly how they treated him? He said that as soon as he got to their lines on Boston Neck, they made him a prisoner and carried him to General [Thomas] Gage, where He was examined and then he was sent to Gould’s Barracks, and was not suffered to go home but once. After He was taken up, for holding a Correspondence with the British, I came a Cross Deacon Caleb Davis;—we entered into conversation about him; He told me that the morning Church went to Boston, He (Davis) received a Bilet from General Gage — (he then did not know that Church was in Town)—When he got to the General’s House, he was told the General could not be spoken with, that He was in private with a Gentleman; that He waited near half an hour,—When General Gage and Dr. Church came out of a Room, discoursing together, like persons who had been long acquainted. He appeared to be quite surprised at seeing Deacon Davis there; that he (Church) went where he pleased while in Boston only a Major Caine [Cane], one of Gage’s aids went with him. I was told by another person whom I could depend upon, that he saw Church go to General Gage’s House at the above time and then He got out of the Chaise and went up the steps more like a Man that was acquainted, than a prisoner.

Sometime after, perhaps a Year or two, I fell in company with a Gentleman who studied with Church—in this coursing about him I related what I have mentioned above; He said he did not doubt that He was in the Interest of the Brittish; and that it was He who informed General Gage that he knew for certain, that a Short time before the Battle of Lexington, (for He then lived with Him, and took Care of his Business and Books) He had no money by him, and was much drove for money; that all at once, he had several Hundred New British Guineas: and that He thought at the time, where they came from.

Benjamin Church was born in Newport, Rhode Island, and graduated from Harvard College in 1754, decades before its medical school was founded. He studied medicine as an apprentice with Joseph Pynchon and later continued his studies in London. He returned to Boston and became a well-regarded physician and surgeon. Among his patients was John Adams.[4]

As friction intensified between the colonies and Britain, church wrote in colonial publications in support of the Whigs. During this time, he was considered an ardent patriot and yet a clandestine Tory sympathizer. He treated some of the wounded of the Boston Massacre, and in 1773 he delivered the Massacre Day oration which marked him as an eloquent orator.

In 1774, Church became active in Massachusetts provincial politics and was made a member of the colony’s Committee of Safety, a body that was charged to prepare for an armed conflict. About this time, Gen. Thomas Gage began receiving intelligence concerning the Provincial Congress’s activities. On February 21, 1775, the Provincial Congress appointed Church and Joseph Warren to conduct an inventory of medical supplies that were on hand for the army and to purchase supplemental supplies that they deemed were needed.

On May 8, 1775, shortly after revolutionary conflict began, Church became a member of an examining board for the army’s surgeons. In effect Church was the first Surgeon General of the United States with the title of “Chief Physician and Director General” of the Continental Army’s medical service. He held this post only from July 27, 1775, to October 17, 1775. Church attempted to standardize the quality of care and establish general hospitals. As troops from around the colonies descended upon the area around Boston however, the other army doctors, now overwhelmed with patients, largely ignored Church’s efforts. When regimental surgeons objected to the director general’s commands, he retaliated by withholding supplies. In time, tempers flared between the army surgeons and Church. General Washington was called upon to calm the medical tempest.[5] During this inquiry Church was formally accused of providing intelligence to the British, “aid or comfort” to the enemy.[6]

Evidence was presented that Church had sent an encrypted letter addressed to a British officer in Boston by way of a former mistress. The letter was intercepted and found to contain an account of the American forces situated around Boston. The disclosure proved to be of not great importance, but it did ask for directions for continuing the correspondence thus providing evidence of Church’s devotion to the crown. The matter was placed before a court of inquiry made-up of general officers, Gen. George Washington presiding. Church admitted authorship of the letter, but he attempted to explain the purpose of the communication by stating it was written to impress the enemy with the Continental Army’s strength and position. He had hoped that this knowledge might prevent an attack while the army was still short of ammunition. The court decided that because Church had ongoing correspondence with the enemy it was recommended that the matter be referred to the Continental Congress for its action.[7]

Church was briefly incarcerated in Cambridge. The Massachusetts provincial Congress arraigned Church on November 2. Despite a powerful defense appeal, he was expelled as a member of the legislative body, an important outcome because Church was a member of the patriot inner circle. The doctor was then incarcerated in Norwich, Connecticut, ironically the birthplace of Benedict Arnold. While in jail he was not allowed pen, ink, or blank paper. During pleasant weather he was permitted outside, but only under guard. He was not allowed to converse with anyone except in the presence and hearing of a town magistrate or the sheriff of the county. Church became ill and in time was returned to Massachusetts under bond and remained imprisoned until 1778. He was named in the Massachusetts Banishment Act of that year and was deported from Boston; his status as a prisoner ended because he was exchanged for a captured American doctor. But the boat on which he sailed from Boston bound to the West Indies never arrived at any port. “Many pious patriots thought God had been more just in his treatment of the traitor than had man.”[8]

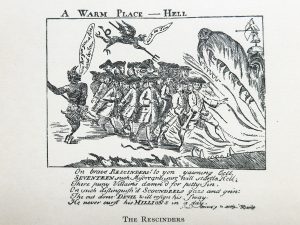

Some years earlier the Son of Liberty Revere was engaged in etching a political image in his shop. Entitled “A Warm Place—Hell”, it was a representation of a violent entrance to an imagined hell through a pair of monstrous open jaws resembling those of a shark from which flames ensued. A satanic image with a large pitchfork was depicted driving seventeen “Rescinders” into the flames. From the devil’s cartoon-balloon mouth were the words, “Now I’ve got you! A fine haul, by Jove!” Those members of the General Court of Massachusetts who voted not to rescind a resolution (sort of political double entendre) were, in essence, disapproved the king’s imposition of the Stamp Act.

By chance Benjamin Church stopped by Revere’s workshop and, after seeing the nearly completed engraving, he authored the following lines to be included beneath the complex image:

On brave Rescinders orders! To yon yawning cell!

Seventeen such miscreants there will startle hell;

These puny Villains, damned for petty sin,

On such distinguished Scoundrels gaze and grin;

The outdone Devil will resign his sway;

He never curst his millions in a day.[9]

Perhaps Church was prescient that day. Paradoxically may have penned an epigram that prophesized his own “Warm Place—Hell” for Paul Revere.

[1]Louis Arthur Norton, “Coppering the Fleet and an American Entrepreneur,” Nautical Research Journal, vol. 59. no. 2 (2014), 120-28.

[2]Mike F. Nola, “Paul Revere and Forensic Dentistry,” Military Medicine, vol. 181, no.7 (July 2016), 714–715.

[3]Edmund S. Morgan, Paul Revere’s Three Accounts of his Famous Ride (Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2000).

[4]Christopher T. Leffler; Stephen G. Schwartz, Ricardo D. Wainsztein, Adam Pflugrath, and Eric Peterson, “Ophthalmology in North America: Early Stories (1491–1801),” Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases Vol. 9 (2017), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5533269/.

[5]Justin McHenry, “John Morgan versus Henry Shippen: The Battle that Defined the Continental Medical Department,” The Journal of the American Revolution, January 28, 2020.

[6]John A. Nagy, Dr. Benjamin Church, Spy: A Case of Espionage on the Eve of the American Revolution (Yardley, Pa.: Westholme, 2013).

[7]“Dr Benjamin Church and the Dilemma of Treason in Revolutionary Massachusetts,” The New England Quarterly 70, no. 3 (1997): 443 – 62.

[8]Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He lived In (New York, NY: The American Past Book of the Month Club, 1942), 304.

[9]Eldridge Henry Goss, The Life of Colonel Paul Revere (Boston, MAS: Plympton Press, 1891), 62.

3 Comments

Greetings Mr Norton,

I enjoyed reading your article about Paul Revere and Benjamin Church, but I thought it important that you should distinguish between the Benjamin Church who fought in King Philip’s War and who captured King Philip, and the Benjamin Church who you discuss in your article?

Perhaps this is something well known to your audience? or perhaps they are the same person? (I think not). Perhaps these two persons are related?

(If so, how distant or closely related are they?)

Thank you, Otis Read

Hi. Great article, but the caption for the Revere portrait has a typo. The artist for this portrait is Gilbert Stuart NEWTON (after a life portrait by Gilbert Stuart)– an important distinction. See: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/49476. Thanks.

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. The error has been corrected.