Though he played a significant role in British victory at the Battle of Camden August 16, 1780, the leadership of Lt. Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon throughout the Camden District (northeast South Carolina) prior to that battle has long gone unrecognized.[1] Few know that Lord Rawdon was charged by his commander, Lt. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis, with subduing rebel insurgents and pacifying the area from June to August 1780. During this time Rawdon attempted to restore royal government, recruit Loyalist militia, and administer the king’s oath of allegiance to local inhabitants.

Nonetheless, Rawdon’s troops soon confronted Patriot militias led by generals Thomas Sumter and Richard Caswell, who attempted to disrupt pacification efforts while encouraging Patriots to prepare for the arrival of an advancing American Continental army under command of Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. Once within the Camden District, Gates’s army sought favorable ground upon which to defeat Cornwallis. Gates’s attack on that fateful morning of August 16, 1780, was repulsed and his army destroyed: a major U.S. battlefield defeat.

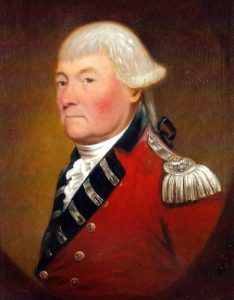

Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings (1754-1826), known as Francis, Lord Rawdon from 1762-1783, was an Anglo-Irish officer who served for almost nine years during the American Revolution. Posted to Boston in 1774, young Lieutenant Rawdon experienced his first combat June 17, 1775, during the Battle of Bunker Hill. Commenting on his bravery, General John Burgoyne would say of him: “Lord Rawdon has this day stamped his fame for life.”[2] Rawdon was soon promoted to captain and given a company command in the 63rd Regiment of Foot (his uncle, Lord Huntingdon, advanced him £1,500 to pay for his commission). Selected as an aide-de-camp to Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, he eagerly wrote his uncle: “I shall learn my business under so able an officer.”[3]

Rawdon accompanied General Clinton during the failed attempt to take Charlestown, South Carolina in 1776, and later that year provided valuable service during the British conquest of Long Island, eventual seizure of New York City.

A staunch believer in the British Empire, Rawdon was instrumental in standing up a Loyalist Irish regiment in 1778—the Volunteers of Ireland. General Clinton believed such a unit would attract and entice Irish soldiers serving in the American army to desert and join the British cause.[4] Chosen by Clinton to command the new regiment, Rawdon was promoted to provincial colonel, whereupon he devoted himself and much of his fortune to the new regiment’s success.[5]

On April 18, 1780, Rawdon and his Volunteers of Ireland arrived in South Carolina. Attached to Lord Cornwallis’s command operating east of the Cooper River, Rawdon and his troops helped to close off the last remaining American line of communications, forcing the surrender of American Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln’s army and the city of Charlestown (today Charleston) on May 12.[6]

After the surrender, Cornwallis and 2,500 infantry and cavalry (including Rawdon’s Volunteers) were ordered by General Clinton, now Commander-in-Chief in North America, to eliminate remaining enemy forces in South Carolina and occupy/pacify the northeast region of the province. Wasting little time, Cornwallis broke camp on May 18 and in due course occupied the town of Camden on June 1.[7] The British proceeded to fortify and convert it into a major logistics base. Rebel property and goods were seized—including the house, mill, and distillery of Joseph Kershaw, a leading Patriot. The town was roughly two city blocks consisting of homes and shops, to which the British added a military barracks, “huts and material to resist hot weather,” and a surrounding palisade log fence.[8] The British fortified Kershaw’s home (converted into British headquarters) as well as the town jail and powder magazine.[9]

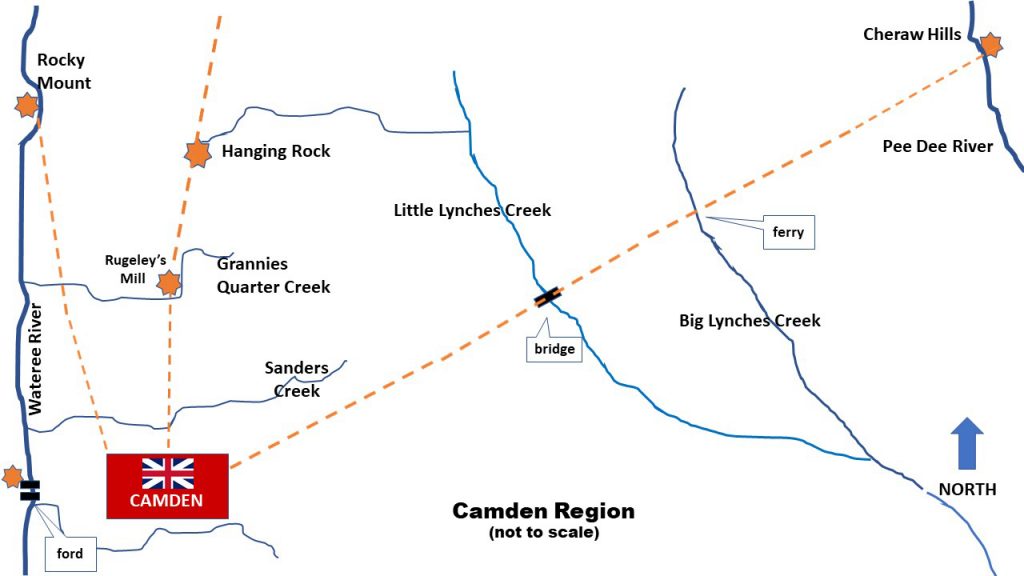

Before returning to Charlestown to govern the colony, Cornwallis appointed Lord Rawdon as the Camden District commander leaving him 700 regulars and Loyalist troops to secure Camden and establish three outposts further north. Likely recommended by local Loyalists, each post was situated on key terrain along roadways or waterways and within mutual supporting distance. Roughly drawn, the Camden region extended from Rocky Mount (Wateree River) on the west, to Hanging Rock (center), and further east to the Cheraw Hills (Pee Dee River), all three extending influence into North Carolina.

Lord Cornwallis had no intention of advancing his army into North Carolina until August or September. This “interval of time,” said Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, “was deemed indispensably requisite for the construction of magazines with properly-secured communications, for a clear establishment of the [Loyalist] militia, and for a final adjustment of those civil and military regulations which in future were to govern Georgia and South Carolina.”[10]

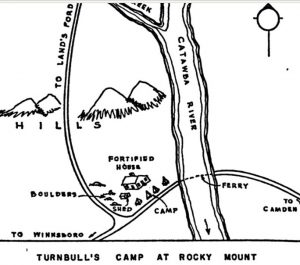

According to Tarleton, the initial disposition of Rawdon’s troops was “Rocky mount . . . occupied by Lieutenant-colonel George Turnbull, with the New York volunteers and some militia;” the 23rd and 33rd regiments of foot, Volunteers of Ireland, British Legion infantry, Hamilton’s corps, and a detachment of artillery, in and about Camden; and to the northeast, the 71st Regiment under Maj. Archibald McArthur at the Cheraw Hills in the vicinity of the Pedee River.[11] The stationing of the 71st Regiment—composed of Scottish Highlanders—was likely deliberate. They were to establish and maintain contact with Scottish Loyalists at Cross Creek, North Carolina, the epicenter of Highlander settlement.

During the first days of June, British emissaries ventured beyond the Camden region and into North Carolina to engage in 1780-style pacification. Inhabitants were expected to: (1) take an oath of allegiance to the king; (2) remain prisoners on parole if formerly in arms against the king’s troops; (3) accept and reestablish royal government; and (4) serve, if called, in the Loyalist militia.

As is the case with many military pacifications, ambiguous policy wrought havoc. General Clinton, who believed Britain should “gain the hearts & subdue the Minds of America,” issued a confusing proclamation on June 3 prior to returning to New York.[12] However well intentioned, what Clinton did was release surrendered Patriot militia from their paroles and require them to take the king’s oath of allegiance with an obligation to serve in the Loyalist militia. For hundreds of paroled Carolinians who might have sat out the war and remained neutral, the proclamation now forced them to choose sides. Most resumed their allegiance to the American cause.[13] Clinton left the enforcement of this new policy to Lord Cornwallis who suddenly found himself mired in Charlestown settling Loyalist vs. paroled-Patriot disputes and other administrative minutia. In Tarleton’s view Cornwallis failed miserably: “He endeavoured so to conduct himself, as to give offence to no party; and the consequence was, that he was able entirely to please none.”[14]

The new policy did not work well at Camden either. When Rawdon advanced his Volunteers of Ireland north into the area of the Catawba River valley in June, he made an unpleasant discovery. Stopping at an Irish settlement in the Waxhaws to assess the allegiances of the Irish settlers, Tarleton reported:

The sentiments of the inhabitants did not correspond with his lordship’s [Rawdon’s] expectations: He there learned what experience confirmed, that the Irish were the most averse of all other settlers to the British government in America.[15]

Nevertheless, while at Waxhaws Rawdon created a committee of inhabitants who seemed to favor the establishment of royal government through a Conservator of the Peace. He also tried to persuade them to form a Loyalist militia, but they declined.[16] Instead, Rawdon concluded that Henry Rugeley, a Loyalist militia leader from Camden, should be sent to administer Waxhaws. He then withdrew his force four days later (June 15) saying, “I do not see that by prolonging my stay here any advantage can accrue; nor do I at present observe any point to be gained by advancing further.”[17]

Rawdon may have made a mistake: First, his withdrawal sent the wrong signal to inhabitants in the immediate vicinity—abandonment. “Rawdens Retreat, I dare Say Confirms them [the inhabitants] in the Belief that we are only here for a few days,” wrote an exasperated Lt. Col. George Turnbull to Cornwallis from his Loyalist outpost at Rocky Mount.[18] And second, Rawdon’s sudden withdrawal south freed up Patriot militia under command of Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford who impatiently waited for an opportunity to attack a large nest of Loyalist militia gathering at Ramsour’s Mill, North Carolina. So long as Rawdon was within a day’s march of Ramsour’s, Rutherford hesitated, considering an attack ill-advised.[19]

Truly the situation of the king’s friends in North Carolina remained tenuous. Ignoring Cornwallis’s dispatches instructing Loyalists to wait for the arrival of his Royal army of liberation, overzealous North Carolina Loyalists encouraged neighbors and sympathizers to form militias. The most well-known leaders were Lt. Col. John Moore and Samuel Bryan. Suddenly, regions of North Carolina which Patriots considered pacified erupted.

Not waiting for Rutherford’s militia, 400 Patriot militia under the command of Col. Francis Locke attacked Moore’s 1,200 Loyalists at Ramsour’s Mill on June 20. It ended in a clumsy mutual bloodletting of farmer versus farmer. The number of casualties (about 170 for each side) may have indicated a draw, but the Rebel militia managed to overawe Moore’s followers and disperse them.

Seventy miles northeast of Ramsour’s, Loyalist Samuel Bryan reacted angrily over Moore’s defeat. Exhorting Loyalists to “rise in arms” and join him in the vicinity of his plantation, approximately 500 men from the Yadkin region rose up and joined him. Warned that Rutherford’s Salisbury Brigade was now moving to intercept him, Bryan’s men retreated south along the Pee Dee River towards the 71st Regiment’s outpost at Cheraw Hills, picking up an additional 300 Loyalists along the way.

Reaching safety, Bryan formed his 800 North Carolina “refugees” in a hollow square where they were warmly welcomed by Maj. McArthur. Commissary officer Charles Stedman saw them:

They presented to our view the horrors of a civil war. Many of them had not seen their families for months, having lived in the woods to avoid the persecution of the Americans. Numbers of them were in rags, most of them men of property. . . . These, with families and friends, they abandoned, to manifest their attachment to the British government.[20]

Bryan’s weary North Carolinians brought alarming news: an American Continental army was approaching from the north.Tarleton remarked:

The news brought by these Loyalists created some astonishment in the military, and diffused universal consternation amongst the inhabitants of South Carolina: They reported, that Major-general de Kalbe . . . was advancing from Salisbury, with a large body of continentals; that Colonel Porterfield was bringing state troops from Virginia; that General Caswall had raised a powerful force in North Carolina; and that Colonel Sumpter had already entered the Catawba, a settlement contiguous to the Waxhaws.[21]

Prior to this, pacification and Loyalist militia recruiting proceeded at a sluggish pace: a few leading rebels had accepted paroles. Believing their cause lost, Col. Andrew Pickens, Col. Isaac Hanes, and Brig. Gen. Andrew Williamson laid down their arms. Although there were signs that not all was well, Cornwallis informed Clinton on June 30: “The surrender of General Williamson at ninety-six and the reduction of Hill’s Iron Works [June 17] by the dragoons and militia under Turnbull has put an end to all resistance in South Carolina.”[22]

Writing to Cornwallis, Rawdon complained that Clinton’s “Proclamation strikes hard at us now, for these frontier districts who were before secured under the bond of Paroles, are now at liberty to take any steps which a turn of fortune might advise.”[23] On July 7 he again vented to Cornwallis saying:

That unfortunate Proclamation . . . has had very unfavourable consequences. The majority of the Inhabitants in the Frontier Districts, tho’ ill Disposed to us, from circumstances were not actually in arms against us. They were therefore freed from the Paroles imposed by Lt. Colonel Turnbull & myself; & nine out of ten of them are now embodied on the part of the Rebels.[24]

Despite this policy mishap, Rawdon soldiered on; he seemed to have a sense of what pacification entailed—good civil governance and protecting loyal inhabitants from insurgents. This included imprisoning 160 suspected rebel sympathizers who refused to join Camden’s Loyalist militia when called out.[25]

Cornwallis advised Lieutenant Colonel Turnbull at Rocky Mount (and likely Rawdon), to appoint a major commandant to each district where the Americans had earlier placed a field officer. Cornwallis suggested,

a very plain Man with a good Character & tolerable Understanding will do, He is to act more in a civil than a Military Character, & as we are not at present troubled with Law, all that is required of him is to have sense enough to know right from wrong & honesty enough to prefer the former to the latter.[26]

Given the opportunity to integrate three newly-raised Loyalist militia companies into his New York Volunteers, he demurred, saying, “I do imagine it woud not answer to Enroll such People in a Corps with ours who are High Disciplined and not Indulged with the same Conditions.”[28]

Intelligence reports convinced Turnbull that “Those Rebells Embodyd Between Charlotburg & Salisbury Over awes great part of the Country and Keeps the Candle of Rebellion still Burning.”[29] But he did react to threats when they materialized. When he received actionable intelligence, he authorized search-and-destroy missions. Informed of “an Iron works about Fifty miles to the westward . . . a Refuge for Runnaways, a Forge for casting Ball and making Rifle Guns &c.” he ordered Loyalist Capt. Christian Huck to demolish it.[30]

Nor was Turnbull adverse to using gold—a useful tool when pacifying occupied areas. He attempted to bribe Patriot Capt. John Henderson (captured at Hill’s Ironworks) into abducting South Carolina governor-in-exile John Rutledge, promising him he would be “Handsomely Rewarded,” and informed Cornwallis saying: “Some times great Villains will do services at all Events. I thought it best to put it to the trial.” But nothing came of it.[31]

Rawdon too was a believer in the power of money. Sending Capt. David Kinlock’s troop of cavalry into the Waxhaws he informed Cornwallis: “I have bidden him try to purchase a Detachment of the Enemy from the Waxhaw people. Gold will, I think, outweigh the spirit of rebellion,” although “it is very strong in my old friends [the Scotch-Irish].”[32]

Countering Rawdon’s efforts, Patriot inhabitants incessantly inveigled soldiers of the Volunteers of Ireland to desert each time they entered the Waxhaws.[33] In disgust, Rawdon offered rewards for the capture or execution of any deserters apprehended.[34] Turnbull complained that “The Rebells have Propagated a story that we Seize all their young men and send them to the Prince of Hesse, it is inconceivable the Damage such Reports has done.”[35]

Rawdon also used “liberal offers of the Secret Service money” to obtain information. In a letter to Cornwallis, he implied that Capt. Alexander Ross, Cornwallis’s aide-de-camp, may have been running several British intelligence operations, but only one of Ross’s “emissaries” (informants) managed to return to give Rawdon any information, making him suspect the other agents had been “taken up.”[36]

Turnbull’s tactical-level fight provides an excellent example of low-level pacification efforts. He was an “on-scene” commander with the best grasp of the situation within the Rocky Mount district. He attempted to tailor his approach to local conditions, and conducted “intelligence-operations . . . at the lowest possible level.” His Rocky Mount outpost was “as close as feasible to the population that it was seeking to secure, relying on local intelligence and security assessments.”[37]

When Turnbull received the news of Moore’s calamity at Ramsour’s Mill, he advanced his New York Volunteers north thirty-five miles to Brown’s Crossroads on his own initiative, informed Rawdon and requested twenty additional dragoons. Turnbull moved north to comfort and protect the Loyalists living in the upcountry; although Rawdon had his doubts, he trusted him, reporting to Cornwallis that Turnbull “would not have made the movement had he not been thoroughly convinced there was no risk in it, &, as I am unacquainted with the circumstances of that district, I repose myself on his prudence.”[38] Instead of recalling Turnbull, Rawdon sent additional arms and ammunition with a 100-man escort made up of the Prince of Wales Regiment, and not twenty but sixty dragoons to support his subordinate.

Keeping Rawdon off balance

News of the approaching Continental army emboldened the Rebels. They established an outpost, “Camp Catawba,” on July 1 at Old Nations Ford under the leadership of South Carolinian Thomas Sumter. His militia, a mix of South and North Carolinians, soon numbered around 600 men (most of them mounted) who were eager to see action. And Sumter was not one to disappoint—he had seen combat early in the Revolution while in command of the 6th Regiment, South Carolina Continental Line. In fact, eighty veteran soldiers of his 6th Regiment joined him at the Catawba encampment.[39]

On or about July 6-7, Rawdon’s situation within the Camden district began to transition from pacification to defense. Rawdon admitted as much when he informed Cornwallis that while he could march his forces into the Waxhaws and “remove Sumpter immediately,” forcing the Patriot commander to retreat to Salisbury, he could not hold the position because he had no “exact account of De Kalb.” Rawdon disclosed that any movement north would put him over two days march from the 71st Regiment at Cheraw Hills leaving that outpost vulnerable.[40]

Rawdon understood the threat posed by Sumter and wanted him gone. He sent Loyalist Colonel Rugeley a list of American officers, empowering him to offer 500 guineas to the man who would lead Sumter into a British ambush.[41] Moving his units to counter perceived threats, Rawdon sent a detachment of New York Volunteers stationed at Camden back to rejoin their unit at Rocky Mount; he also ordered McArthur to fall back from the Cheraw Hills position leaving only light troops in the Pee Dee region once word was received that DeKalbs’ army was at Salisbury (an order which McArthur ignored). Meanwhile, he ordered the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers under Maj. Thomas Mecan to make a quick thrust into the Waxhaws “to disarm such of the Inhabitants as did not enroll in the Militia.”[42]

Mecan may have made it only as far north as Hanging Rock. Hearing the British were again moving north, Sumter’s entire 600-man force moved south to engage them but found nothing. Falling back to his Catawba camp, Sumter and his officers decided to send their men home for several days to assist with the harvest as well as reprovision and enlist additional recruits.[43]

This intelligence reached Lieutenant Colonel Turnbull at Rocky Mount who ordered Captain Huck to capture two influential rebel leaders—Capt. John McClure and Col. William Bratton. It was believed McClure was at home reaping grain, while Bratton was rumored to be posting proclamations and promising pardons to neighbors who had taken the king’s oath.[44]With a force of thirty-five Legion Dragoons, twenty mounted infantry of the New York Volunteers and fifty militia, Huck moved north towards Fishing Creek on July 10.

Capt. Christian Huck and those like him help, in part, to explain why British attempts at pacification failed in the Camden District and other areas occupied by British forces. Huck was no saint. He threatened and mistreated local inhabitants with whom he came in contact; there was no reconciliation or neutrality in most of his actions. His men robbed and plundered, they humiliated friend and foe alike and at times detained not just men, but women and children. Huck used terrorist-style threats when interacting with Patriot families, subjecting them to indiscriminate punishments which included violence and threats of hanging.

In the early morning of July 12, Huck and his troops, encamped at James Williamson’s plantation, were attacked by several elements of Sumter’s militia led by local Patriot officers. Huck was killed and his command routed and destroyed; few of his men escaped unscathed. The Patriot victory became known as “Huck’s Defeat” and resonated throughout the upcountry—Patriots rallied around Sumter’s militia. It confirmed Rawdon’s worst fears that the “greater part of the Waxhaw people have joined the Rebels; the rest live under the Enemy’s protection.”[45]

While Rawdon fretted over the movements and the whereabouts of DeKalb’s Continentals and Gen. Richard Casswell’s North Carolina militia to his northeast, Sumter strategized that a successful attack on Turnbull’s Rocky Mount camp might force Rawdon to abandon all his northern outposts.

On July 28, Sumter with 600 mounted men proceeded down the Catawba River towards Rocky Mount. Meeting with young cavalryman Maj. William Davie and his North Carolina dragoons, it was agreed that Davie would launch a diversionary attack on Rawdon’s outpost at Hanging Rock.

Outnumbering Turnbull two to one, Sumter’s men attacked Rocky Mount July 30 and immediately encountered stiff resistance from 150 stubborn New Yorkers and 100 Loyalist militia. According to Patriot Col. William Hill, it became apparent that the Loyalists had fortified a large clapboard house:

the Enemy had wrought day and night and had placed small logs about a foot from the inside of the wall and rammed the cavity with clay, under this delusion we made the attack; but soon found we could injure them noway, but by shooting in their portholes.[46]

After three failed assaults and two attempts to set the fortified buildings on fire (a major thunderstorm interfered), Sumter reluctantly withdrew after eight exhausting hours—bent but not broken.

Davie, on the other hand, executed a successful if not textbook raid on a contingent of Loyalist cavalry at Hanging Rock in front of the onlooking Loyalist garrison, inflicting significant losses without losing a man. His raid exposed the vulnerabilities of that unfortified outpost. In fact, Davie’s report was so encouraging that Sumter revised his plans: he determined to attack Hanging Rock.[47]

Although the antagonists may not have recognized it, Rocky Mount signaled a major shift in American and British strategies within the Camden region. For Patriot forces it heralded a shift from erratic-irregular to quasi-conventional-style warfare calculated to support the arrival of a Continental army. For Rawdon, it portended a defensive strategy compelling him to defend the Camden District and prepare for impending battle.

Surveying his situation the day after Turnbull’s successful defense of Rocky Mount, Lord Rawdon could take pride in the fact that Camden District and his outposts continued to successfully defend themselves and protect the king’s loyal subjects in their peaceful pursuits, but he was under no illusions: both he and Cornwallis were convinced the Rebels intended “to commence offensive Operations immediately.”[48]

[1]For discussion purposes, this author defines the greater Camden District to include Rocky Mount, Hanging Rock and Cheraw district.

[2]Paul David Nelson, Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Marquess of Hastings: Soldier, Peer of the Realm, Governor-General of India (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Press, 2005), 12.

[3]Francis, Lord Rawdon to uncle Francis Hastings, 10th Earl of Huntingdon in Nelson, Francis Rawdon-Hastings,19.

[4]Rawdon to John Andre, May 21, 1780, www.royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/voi/voilet8.htm.

[5]“The Volunteers of Ireland,” The American Catholic Historical Researches, New Series, Vol. 3, No. 4 (October, 1907), 339-351.

[6]Carl Borick, A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 251.

[7]Cornwallis dispatched Tarleton’s Legion to pursue Col. Abraham Buford’s 350 retreating Continentals. Tarleton attacked and defeated Burford on May 29 at Waxhaws, South Carolina, destroying Buford’s command and earning a reputation for ruthlessness and cruelty. Thomas J. Kirkland and Robert M. Kennedy, Historic Camden Part One, Colonial and Revolutionary (Columbia, SC: State Company, 1905), 142–143.

[8]Banastre Tarleton, A history of the campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the southern provinces of North America, (Dublin: Colles, 1787), 89.

[9]Kershaw-Cornwallis House, www.scpictureproject.org/kershaw-county/kershaw-cornwallis-house.html.

[10]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 88.

[12]Nelson, Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 33; Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 73-74.

[13]Or, did Patriots simply recover from the “shock and awe” of a British occupation and begin to resist?

[14]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 92.

[16]Rawdon to Cornwallis, June 11, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/123-125, Cornwallis Papers, British National Archives, Kew, UK.

[18]Turnbull to Cornwallis, June 16, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/162–163), Cornwallis Papers.

[19]Robert D. Bass, Gamecock: The Life and Campaigns of General Thomas D. Sumter (Holt, Rinehart and Winston. New York, 1961), 57

[20]Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, Volume2, (London: J. Murray, 1794), 197.

[21]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 94.

[23]Rawdon to Cornwallis, June 22, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/179–182, Cornwallis Papers.

[24]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/252–255, ibid.

[25]Nelson, Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 61.

[26]Cornwallis to George Turnbull, June 16, 1780, PRO 30/11/77/11–12, Cornwallis Papers.

[27]Turnbull to Cornwallis, July 6, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/250-251, ibid.

[28]Turnbull to Cornwallis, June 12, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/147–148, ibid.

[29]Turnbull to Cornwallis, June 16, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/162–163, ibid.

[30]Turnbull to Cornwallis, June 15, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/158–159, ibid. This was William Hill’s Iron Works, a facility capable of producing a variety of weapons including small cannons. See Scoggins,The Day it Rained Militia, 139.

[31]Turnbull to Cornwallis, June 19, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/171–172, ibid.

[32]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/252–255, ibid.

[33]John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1997), 131.

[34]Kirkland and Kennedy, Historic Camden, 214.

[35]Turnbull to Cornwallis, June 15, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/158–159, Cornwallis Papers.

[36]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/252–255, ibid.

[37]Turnbull’s behavior closely mirrors today’s Joint Publication 3-24, Counterinsurgency (Joint Chiefs of Staff, April 25, 2018) Employment Considerations, Decentralized Execution, III-28.

[38]Rawdon to Cornwallis, June 22, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/179–182, Cornwallis Papers.

[40]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/252–255, Cornwallis Papers; Otho Williams, “A Narrative of the Campaign of 1780,” in William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathaniel Greene (Charleston, SC: A.E. Miller, 1822), 485.

[42]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 10, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/264-265, Cornwallis Papers.

[43]Michael Scoggins, The Day it Rained Militia: Huck’s Defeat and the Revolution in the South Carolina Backcountry May-July 1780, (The History Press, Charleston, SC, 2005), 101.

[45]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/252–255, Cornwallis Papers.

[47]Davie attacked three companies of Bryan’s North Carolina Loyalists. See Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, 1812 (New York: University Publishing, 1869), 176.

[48]Cornwallis to Clinton, July 14, 1780, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr15-0191.

4 Comments

On July 1, 1780, Rawdon wrote Rugeley that he would award ” the inhabitants ten guineas for the head of any deserter belonging to the Volunteers of Ireland, and five only if they bring him in alive”.

The letter written to Rugeley was genuine, but according to Rawdon, merely a threat to scare them. He wrote on 24 December 1780 of the incident: “You must expect to hear me talked of as a monster of cruelty: For the Rebels who have in this Country been guilty of the most atrocious barbarities, never fail to raise the most violent outcries when we punish the treachery of their partisans with the severity due to it. I esteem it highly dishonest to let the fear of vulgar obloquy intimidate one from the performance of what one knows to be one’s duty: Therefore, under any circumstances that require stepping beyond the line of precedent, I must always be very liable to incur misrepresentation. Washington, with a view of sowing dissention, sent to Sir H. Clinton a letter of mine which was intercepted by Gates; with a grievous complaint against it’s severity; It was a Lettre Fulminante, calculated to terrify our pretended friends in the Country, from enticing the troops to desert; & it will give a mighty pretty idea of my character, if it appears in a London news-paper. A letter of similar spirit from Ld. Cornwallis, was sent at the same time by Washington to the Comr. in Chief: The latter does not appear to have understood his antagonist’s drift. I think I have worse success in letters than any man living: I suppose it is because I write in general as I speak, from the immediate emotion of my heart, without considering much, what opinion may in consequence be passed upon me.” Source: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, Granard Papers: Letters from the 1st Marquess of Hastings, 1776-1781, T3765/M/4/2, No. 19.

Thanks for providing context to the quote. I came across it while researching a related topic and it struck me as rather extreme, even for the time. I was generally aware of the letter being elevated to American commanders. To your point, I have not come across any evidence of deserter’s heads being brought in during that campaign.

From what I can surmise you’ve been doing lots of research on Rawdon. Hopefully, he will the topic of a forthcoming publication?

Hey Doug. Yes, I am working on a major Rawdon project for the State of South Carolina’s 250th Commission. Stay tuned! I neglected to mention above, that extract I posted of Rawdon’s was written to his mother…