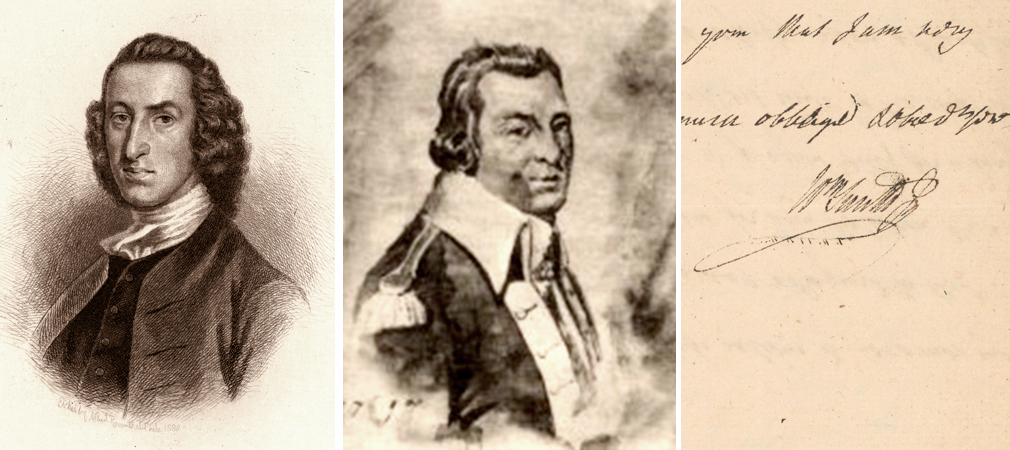

John Adams was making his way from Massachusetts to Pennsylvania for a convening of the delegates tasked to craft a response to the Coercive Acts when he and his entourage arrived in Manhattan on the morning of Saturday August 20, 1774. He met that day with numerous dignitaries and dined late into the evening at Hull’s Tavern with a group that included the attorney John Morin Scott. That conversation must have been productive because early Monday morning Adams joined Alexander McDougall from the Sons of Liberty on a coach ride to break fast at the Scott home in what was then still countryside in today’s Midtown Manhattan. John Morin Scott was one third of the powerful triumvirate of New York attorneys that included William Livingston and William Smith Jr. Judging by the tone of Adams’ diary entries, he seems not to have known the three New Yorkers personally until this visit, but he clearly was aware of their work and reputation. Adams wrote that Monday night that

Mr. Scott, Mr. William Smith and Mr. William Livingston, are the Triumvirate, who figured away in younger Life, against the Church of England—who wrote the independent Reflecter, the Watch Tower, and other Papers. They are all of them Children of Yale Colledge. Scott and Livingston are said to be lazy. Smith improves every Moment of his Time. Livingstone is lately removed into N. Jersey, and is one of the Delegates for that Province.[1]

The next day Adams ate a late lunch with McDougal, Scott, William Livingston’s brother Philip and others at the home of Peter Van Brugh Livingston, yet another sibling in that clan.[2]

Whatever John Adams thought of William Livingston, William Smith Jr., and John Morin Scott personally—and going by his writings Adams’s outlook fluctuated moment to moment—there is no dispute that the Triumvirate played crucial roles in both colonial life and the American Revolution. These three, and men like them, were born in colonial America in the first decades of the eighteenth century. These were the sons—and increasingly grandsons—of men born in the British Isles who had come to the New World in the wake of England’s 1664 victory over the Dutch and transformation of New Netherland into New York. Some lived in grand manors spread over tens or even hundreds of thousands of acres in the Hudson Valley and Upstate New York, their fields tended by tenants and enslaved people; others inhabited the city and worked as artisans, merchants, and lawyers conducting trade with the mother country and sister colonies. New York’s parvenus often intermarried with the Old Dutch, creating economic and familial ties that would last for generations. Yet somehow the descendants managed to maintain their religious, cultural, and linguistic ties to England, Scotland, and the rest of the Anglophone world. These sons of Britannia built many of colonial New York’s economic, educational, and social institutions, some of which still exist today. Despite everything they built in British North America, many would ultimately break away and help create the new nation.

Due to war and demographic change Dutch authority in North America began waning in the mid-seventeenth century. Events reached a turning point in 1664 when Petrus Stuyvesant surrendered New Netherland to the forces of Charles II. The English king granted his brother James, Duke of York, a major concession along the Eastern Seaboard. Dutch influence in the New World nonetheless remained strong. A Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67) gave way to a Third (1672–74), during which the Dutch even reclaimed Manhattan for a time. By February 1674 the British emerged ultimately victorious and in control once again.

New York remained a proprietary colony until Charles II’s 1685 death and James’s ascension to the British throne. New York then became a royal colony, and would remain so for the next nine decades. Through the remainder of the seventeenth century, despite conflicts with other European nations both on the European continent and in the New World itself, the British consolidated their influence in North America. They achieved greater stability in the British Isles as well. The English and Scottish parliaments passed Acts of Union in 1706 and 1707 and became the Kingdom of Great Britain on May 1, 1707. Meanwhile the British institutionalized their gains across the Atlantic. One group of historians write that “The basic constitutional principles of provincial New York were hammered out in the period 1708-1739. Gradually, constitutional procedures developed that were similar to but not identical with those of Great Britain.”[3]

One of the earliest to recognize and take advantage of the evolving order was Robert Livingston, who was born in the village of Ancrum, Scotland in 1654 and grew up in the port city of Rotterdam where he became fluent in Dutch. This fluency served him well when around the time of the English takeover in the mid-1660s he moved to the New World, settling eventually in what is today Albany. On July 9, 1679 he married Alida Schuyler van Rensselaer. The couple were fruitful and welcomed the fourth of their eventually nine children, Philip, on their seventh wedding anniversary in 1686. Two weeks later on July 22, 1686 Royal Governor Thomas Dongan issued Albany a municipal charter. That same day Governor Dongan also granted Robert Livingston a land patent of approximately 160,000 acres in the Hudson Valley.

The Scott clan too came from Ancrum. In the seventeenth century different branches of the family were already moving back and forth across the Atlantic and involving themselves in the affairs of the competing European powers in both the Old and New Worlds. One of them, a Capt. John Scott, settled in New York City in the early eighteenth century, where his first child and namesake was born in 1702. John the Younger became a merchant and in his twenties married Marian Morin, who begat their only child, John Morin Scott, in 1730.

William Smith was born in Newport Pagnell, England in the late 1690s, the oldest son of Thomas and Susanna. In 1715 the family moved to New York City, where Thomas quickly became involved in public affairs. Among other endeavors, he was one of the founding members of the First Presbyterian Church in New York City. Young William matriculated at Yale, from where he graduated in 1719. He received an advanced degree from that same institution in 1722 and stayed on as an instructor. In this time he also became involved in what became known as the Yale Apostasy, a dispute between Anglicans and Presbyterians over the direction of the college. Though just in his late twenties, William Smith was offered the Yale presidency.[4] Instead he returned to New York City, passed the bar in 1724 and entered the legal profession. One of his closest associates was the Scotsman James Alexander, who may or may not have come over on the same ship with the Smiths in 1715. (Accounts vary; Alexander’s arrival may have been in 1716.) Both also had growing families. James’s son, William Alexander, was born in 1726. William and wife Mary welcomed William Smith Jr. in 1728.

As British influence became increasingly codified James Alexander and William Smith were making names for themselves. The two attorneys also proved unafraid to stand against colonial authority, most notably in articles published in the New York Weekly Journal in criticism of Gov. William Cosby. This periodical was printed by a German immigrant named John Peter Zenger, who soon found himself sitting in the City Hall jail on Wall Street on charges of seditious libel for things published in the newspaper about Governor Cosby. Zenger was acquitted in 1735, though not before Chief Justice James De Lancey disbarred defense attorneys Smith and Alexander on April 16, 1735 at the start of the trial. Zenger’s acquittal was both a victory for freedom of speech and precursor of things to come. Alexander and Smith were restored to the New York Bar after Cosby passed away in 1736.

Many wealthy colonists sent their offspring abroad to Oxford or Cambridge in preparation for entering business or the law, but Philip Livingston, William Smith, and the widow of John Scott educated their sons in British America. Between 1731 and 1741 four of Philip Livingston’s boys—Peter Van Brugh (1731), John (1733), Philip (1737), and William (1741)—graduated from Yale. In 1745 Philip Livingston, who had become the second lord of Livingston Manor after his Ancrum-born father’s 1728 death and expanded the family’s already considerable wealth through a number of enterprises—including the human slave trade—donated £28 sterling to Yale in appreciation for the education his sons had received there. Eleven years later school administrators used Livingston’s funds to create Yale’s first endowed professorship.[5] William Smith—himself a Yale graduate who in the 1720s had turned down the college presidency—sent his son there as well. William Jr. graduated in 1745. John Morin Scott received his degree in New Haven the following year.

The lives of these young men intertwined via marriage and career in the insular milieu of New York’s colonial elite. They were fortunate to have come of age when they did. Historian Milton M. Klein explains that “The transformation of the law in colonial New York took place about the middle of the [eighteenth] century, coincident with a period of marked business expansion. Heightened commercial activity produced an astonishing increase in litigation, and this, in turn, created and enlarged demand for legal services.”[6] William Livingston clerked in the law office of James Alexander. Chafing under Alexander’s abrasive style, he moved to the practice of William Smith. There he was joined by William Smith Jr., and John Morin Scott. The Triumvirate came into their own under William Smith’s tutelage.

William Livingston had chafed under James Alexander’s strict ways at the office, but he could not escape the Alexander family’s grasp at home. On November 3, 1739 William’s brother, Peter Van Brugh, had married Mr. Alexander’s daughter, Mary. Nine years later on March 1, 1748 William’s sister, Sarah van Brugh Livingston, married Mr. Alexander’s son William, thus Lord Stirling himself became William, Philip, and Peter Van Brugh Livingston’s brother-in-law. Four years after that marriage William Smith Jr. joined the extended Livingston family as well, marrying Janet Livingston on November 3, 1752.

Personally, professionally, and politically the mid-eighteenth century was a time of challenge and opportunity for energetic and intelligent men in British Colonial America. Still, the New York Province lagged in many ways. It says something about the colony’s intellectual development, or dearth thereof, that Massachusetts (Harvard, 1636), Virginia (William & Mary, 1693), and Connecticut (Yale, 1701), all had institutions of higher learning half a century and more before New York. Other, even smaller, communities too had come first. The New Light Presbyterians, for instance, established the College of New Jersey in Elizabeth in 1746 before eventually moving to Princeton. This involvement of religious orders in establishing learning institutions was hardly unique to the Presbyterians. Puritans had been instrumental in founding what became Harvard and Yale, and Episcopalians faithful to the Church of England (Anglicans) had been involved in the creation of William & Mary. Now the Anglicans wanted to do the same in Manhattan.

Everyone recognized the need for an institution of higher learning for New York City. In 1737, the year Philip Livingston received his degree from Yale, there was a sum total of fifteen college graduates in the entire Province of New York.[7] That number had not grown significantly in the succeeding years. In the early 1750s the Triumvirate found themselves in the middle of a dispute with colonial authorities and the Church of England (Anglicans) over the founding of King’s College. At stake—as William Livingston, William Smith Jr., and John Morin Scott saw it—was the degree to which the Church of England would exercise authority over the school. The three Presbyterians expressed their concerns regarding the college and other matters in “The Independent Reflector,” a magazine they formed in November 1752 and which lasted for a year. They were only somewhat successful in curbing Anglican power upon King’s College. In response the Triumvirate joined three associates in founding the New York Society Library, which they envisioned as a secular counterweight to the new college. The modest library opened on the second story of City Hall in autumn 1754, just down the street from the new college whose classes were meeting on the grounds of Trinity Church.

That same year the international stakes had grown exponentially. On May 28, 1754 Lt. Col. George Washington of the Virginia Militia and his Native American allies under the leadership of the Mingo leader Tanacharison led a small raid against French forces in western Pennsylvania. It was the opening skirmish in the French and Indian War. Men such as Benjamin Franklin had been concerned about Native American relations and intercolonial affairs for the past several years, and as it turned out Franklin and an entourage of Pennsylvania colonists arrived in New York City the very week after Washington’s battle to discuss such matters. On approximately June 8 Franklin and the Pennsylvanians met with James Alexander in New York City regarding an upcoming conference to be held in Albany. On June 19 James De Lancey—who had disbarred James Alexander and William Smith nineteen years previously during the Zenger affair—convened representatives from several colonies at the Albany Congress in the courthouse of that town. As lieutenant governor, De Lancey presided. William Johnson, an Irishman and British officer who had come to America in 1738 and in the succeeding years cultivated strong military and commercial ties to the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, also played a prominent role. So also did William Smith. William Livingston and William Alexander, whose father James had met in New York City weeks earlier with Franklin and others, also attended.

Commissioners and attendees from the seven participating colonies who met at the Albany Congress argued and debated in the summer heat in the ensuing weeks. Participating and pressing their own interests too were Native American representatives from the Six Nations. The hosts presented the Native Americans with gifts of wampum and other items in gestures of faith and hope that the Iroquois Confederacy would not ally with the French. On July 10 the commissioners released a Plan of Union largely drafted by Benjamin Franklin listing a number of recommendations relating to Native American treaties, colonial trade, taxation, and other issues that the colonists might pursue in greater unison in the coming years. The victim of Crown and Parliament’s rigorous guarding of their own prerogatives and the escalating violence of the French and Indian War, the Albany Plan came to naught.

The Livingstons, Scotts, Smiths, and Alexanders were all active in various capacities for the duration of the conflict. This is not surprising given the centrality of New York State in military campaigns, the threats posed by the French to British interests in the North America, and the stakes involved for the Livingston faction personally, politically, and financially. William Alexander became an aide and secretary to British commander Gen. William Shirley. Alexander wrote to Benjamin Franklin on Shirley’s behalf from Albany on November 12, 1755 briefly explaining the logistics and supply situation, mentioning the death that summer of Gen. Edward Braddock, and asking the scientist and statesman to say hello to his son William.[8] In that missive he also mentioned passing receipts on Franklin’s behalf to his brother-in-law Peter Van Brugh Livingston, who as a New York merchant was expediting defense contracts and providing matériel to the British war effort. Philip Livingston remained active in New York City politics and invested in several privateering ventures against the French. As if to accentuate their British ties, on November 19, 1756 Philip and dozens of others including his brother William and their friend John Morin Scott gathered in New York City and founded the Saint Andrew’s Society of the Province of New York. Philip Livingston was elected its first president. He continued as a New York City alderman and in 1759 becoming a member of the New York General Assembly.

The Livingston and their associates were doing equal parts good and well during the conflict. William was especially active. One historian explains that throughout the French and Indian War:

Lawyers benefited from the flood tide as well as the ebb of commerce, and the years of the French and Indian War proved especially remunerative to the legal community. New York City became the hub of the imperial supply line to the colonies, and the upsurge of business ended the city’s “bad times.” Lawyers reaped the harvest of maritime litigation that followed, much of it stemming from ship seizures, captured cargoes, and the suppression of the illicit trade with the French and Dutch West Indies. Maritime cases were heard in the Court of Vice-Admiralty, which sat in New York City. [William] Livingston was among the few attorneys who virtually monopolized the practice of this court.[9]

William was thus understandably committed to the British court system as practiced in the New York province. Intellectually he was as well. In 1762 he and William Smith Jr. published “Laws of New-York, from the 11th Nov. 1752, to 22d May 1762.” This was the second in a two-volume set. Over ten years previously, the New York General Assembly had commissioned the two young lawyers to author “Laws of New-York, from the year 1691, to 1751.” That monograph provided a digest of colonial New York jurisprudence from the early years of the rule of William and Mary to just past the midpoint of the eighteenth century. Now the 1762 volume continued that project, and included many laws pertaining to the still very much ongoing war against the French and their Native American allies.

The Treaty of Paris ended the war on February 10, 1763 with the British grip on North America stronger than ever. Peace, however, has a way of bringing its own challenges, not least hubris and overreach. The Sugar and Currency Acts of 1764 were followed the next year by a Quartering Act mandating that colonial governments house and provision British troops and a Stamp Act on paper goods. From the colonists’ point of view the Stamp Act in particular was a bridge too far. Its duties on dozens of items, not least legal and financial documents, was of special concern to New York’s lawyers and merchants. John Morin Scott and others created the Sons of Liberty in response. In early October 1765 representatives from nine colonies gathered at City Hall on Wall Street to debate what to do. Part of the New York contingent included Philip Livingston and his cousin Robert R. Livingston.

For two weeks the Stamp Act Congress debated and on Saturday the 19th issued a thirteen-point Declaration of Rights outlining colonial concerns. The delegates were serious about repealing the Stamp Act, but showing themselves to be more conservative than the Sons of Liberty, underscored their faith and loyalty in a short epilogue:

Lastly, That it is the indispensable duty of these colonies, to the best of sovereigns, to the mother country, and to themselves, to endeavour by a loyal and dutiful address to his Majesty, and humble applications to both Houses of Parliament, to procure the repeal of the Act for granting and applying certain stamp duties, of all clauses of any other Acts of Parliament, whereby the jurisdiction of the Admiralty is extended as aforesaid, and of the other late Acts for the restriction of American commerce.[10]

The New York Mercury printed on November 7 that in late October New York merchants had issued a non-importation agreement agreeing not to trade in British goods.[11]

London authorities repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766 but issued a Declaratory Act emphasizing Parliament’s legal right to tax the colonists. True to that legislation’s intent, they followed up with the so-called Townshend Duties on myriad goods and services. Meanwhile politics in New York continued at the local and state level. For generations the Livingston and De Lancey families and their respective allies had engaged in bitter political infighting, though sometimes uniting when their vested interests made cooperation mutually beneficial. The late 1760s was not one of those periods. In 1768 both Philip Livingston and John Morin Scott ran for seats representing the city in the New York General Assembly. Bitterly opposed to them was James De Lancey, the son and namesake of the onetime state chief justice who had died in 1760. Livingston was all but guaranteed an assembly seat on name recognition alone. Therefore, in the words of historian Luke J. Feder, the De Lancey clique “focused all of its efforts on ruining the reputation of John Scott Morin.”[12] The strategy worked at least at the local level, though the Livingston faction maintained its majority colony-wide. The feud continued into the 1770s, with each faction gaining and losing influence as circumstances evolved.

Events accelerated in the 1770s, though on some levels life went on. For instance, members of The Moot, a professional organization of lawyers whose ranks included William Livingston, William Smith Jr., John Morin Scott, John Jay and others, continued meeting regularly in taverns and eating places to discuss the minutiae of jurisprudence. Men tried to thread the needle between their support for British authority and resistance to Crown and Parliamentary policy, but each succeeding crisis created its own time for choosing. William Livingston himself left New York City altogether in 1772 and sought escape as a gentleman farmer, building an estate, Liberty Hall, in Elizabethtown, New Jersey.

Shortly after the middle-aged William Livingston’s arrival in Elizabethtown, the young Alexander Hamilton appeared there as well. The teenager had survived a major hurricane in St. Croix in August 1772 and left shortly thereafter to pursue an education in North America. Livingston encouraged and mentored Hamilton for several months in Elizabethtown, effectively taking the young man into his family and prepping Hamilton before his matriculation at King’s College. William’s daughter Sarah married John Jay on April 28, 1774 in the Great Hall of the spacious Livingston home. Over the course of that year as news of the Coercive Acts crossed the Atlantic, there were calls for a meeting among colonists to craft a response. On Monday September 5, 1774 William Livingston walked into Philadelphia’s Carpenter’s Hall alongside his brother Philip Livingston and son-in-law John Jay of New York at the First Continental Congress. The following April Philip was leading a provincial convention at the Exchange Building in Lower Manhattan to choose delegates to a Second Continental Congress when news arrived of the events at Lexington and Concord.

British authority in New York was collapsing and into the void New Yorkers, like colonists elsewhere, were filling the breach. On May 23, 1775 Peter Van Brugh Livingston was appointed president of New York’s Provincial Congress. Just over one month later he sent representatives across the Hudson River to New Jersey to escort the newly appointed commander in chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, into the city. General Washington convened with Peter V.B. Livingston and other members of New York’s Provincial Congress before hurrying on to Cambridge, Massachusetts to organize his nascent forces. Washington and the Continental Army seized Dorchester Heights on March 4, 1776, and less than two weeks later the British army left Massachusetts to regroup temporarily in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In late June spotters announced the arrival of Admiral Richard Howe’s fleet off the coast of Staten Island. In the following weeks Admiral Howe and his brother, Gen. William Howe, prepared their men for the battle everyone knew was coming. John Morin Scott, for one, had sensed the coming danger and sent his daughter Mary to Liberty Hall in Elizabethtown to stay with the William Livingston family.[13] The engagement came in late August. Gen. William Alexander and the Maryland 400 fought Gen. Charles Cornwallisand his men near Brooklyn’s Old Stone House. Alexander was captured, though not before giving Washington, Alexander McDougal, John Morin Scott and other leaders a chance to regroup and assess in Brooklyn Heights at the Council of War before the evacuation across the East River.

The Patriots were ultimately pushed out of Manhattan. The ensuing years were difficult ones in New York City. The British held the city from summer 1776 until late November 1783. Fires in 1776 and 1778 destroyed much of the already overburdened city’s housing stock and infrastructure. William Livingston had been fortunate to leave when he did in 1772. He became the state of New Jersey’s first governor in 1776, taking over from the final British colonial executive, William Franklin. He would hold that gubernatorial position until his death in 1790. William Livingston was also one of the framers of the United States Constitution. His brother Philip Livingston’s Brooklyn estate was taken over by the British and used as a field hospital. Philip died in York, Pennsylvania when the Continental Congress was convening there in June 1778, less than two years after he had signed the Declaration of Independence. He rests in York’s Prospect Hill Cemetery. William and Philip’s good friend John Morin Scott served in a number of military and civilian capacities until the war’s end and died in September 1784. Among other things he helped William and Philip’s brother-in-law, John Jay, write the New York State Constitution along with their cousin Robert R. Livingston and others. William Alexander,Lord Stirling, did not live to see the war’s end, having died in January 1783. Conspicuously absent in these events was William Smith Jr. The attorney who had been one-third of the Triumvirate did not join the Patriot cause. Though a staunch Loyalist, Smith lived for part of the war at Livingston Manor north of Manhattan under the protection of his longtime friends before relocating to British-occupied New York City. After the war he spent some time in London and eventually took a post in Canada, where he became Chief Justice of the Province of Quebec.

Little physically remains of New York City’s Revolutionary War experience. Many of the social and cultural institutions created in the time of British rule by these men and others like them do remain. King’s College became Columbia University after the defeat of the British and moved uptown long ago. After several moves over the centuries the New York Society Library today stands on East 79th Street. The Saint Andrew’s Society of the State of New York is still meeting regularly.

For all they had done via their polemical essays, legal scholarship, jurisprudence, and public service, the Triumvirate of William Livingston, John Morin Scott, and William Smith Jr., remain largely unknown today. When recently asked by a visitor to Liberty Hall Museum (the New Jersey estate of William Livingston that since May 6, 2000 has been open to the public for tours, weddings, and cultural events) why this founder is so little known today, the guide speculated that it is largely due to Mr. Livingston’s not having fought directly in battle. Livingston never engaged the Redcoats in any dramatic battles but he did serve as a brigadier general in the New Jersey Militia for a time, and proved a responsive and dedicated soldier. Washington Irving in volume two of his “Life of George Washington” describes Livingston as “a man inexperienced in arms, but of education, talent, sagacity and ready wit.”[14] His greatest military contribution was rallying troops into defensive positions when the Howes arrived off the New York and New Jersey coasts. Livingston resigned his commission in 1776 to become the wartime governor and proved equally effective in organizing men and matériel in this civilian capacity. Because of New Jersey’s geography and military significance, Governor Livingston communicated frequently with General Washington throughout the war.

Livingston’s friend John Morin Scott did fight in the army, and was wounded at White Plains. He too resigned his commission early in the war, in March 1777, before serving the Patriot cause in other ways. Scott then died in 1784 at just fifty-four before having the opportunity to contribute to the growth of the nation or tell his own story. The Loyalist William Smith Jr. had left entirely and eventually settled in British Canada.

The Triumvirate were largely supplanted in the historical memory by other, usually younger men from their inner circle whom they had groomed for public life and service. These included William Livingston’s protégé Alexander Hamilton, son-in-law John Jay, and Jay’s good friend and onetime law partner Robert R. Livingston, the younger cousin of William and Philip who among other things had served on the Committee of Five at the Second Continental Congress that drafted the Declaration of Independence; he later negotiated the Louisiana Purchase during the Jefferson Administration.

[1]John Adams, “1774. Aug. 22. Monday,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0004-0005-0010.

[2]John Adams. “1774 Aug. 23. Tuesday,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0004-0005-0011.

[3]David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A Short History of New York State (Ithaca: Cornell University Press for the New York State Historical Association, 1957), 39.

[4]Maturin L. Delafield,“William Smith — Judge of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York,” Magazine of American History 6, no. 4 (April 1881): 265.

[5]AntonyDugdale, J.J. Fueser, and J. Celso de Castro Alves, Yale, Slavery and Abolition (New Haven: The Amistad Committee, Inc., 2001), 3.

[6]Milton M. Klein, “The Rise of the New York Bar: The Legal Career of William Livingston,” The William and Mary Quarterly 15, no. 3 (July 1958): 335.

[7]Robert W. Anthony, “Philip Livingston —A Tribute,” The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association 5, no. 4 (October 1924): 311.

[8]WilliamAlexander to Benjamin Franklin, November 12, 1755, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-06-02-0109.

[9]Klein. “The Rise of the New York Bar,” 343.

[10]Journal of the First Congress of the American Colonies, in Opposition to the Tyrannical Acts of the British Parliament. Held at New York, October 7, 1765 (New York: E. Winchester, 1845), 27-29.

[11]“New York Merchants Non-Importation Agreement; October 31, 1765,” avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/newyork_non_importation_1765.asp.

[12]Luke J Feder, “’No Lawyer in the Assembly!’: Character Politics and the Election of 1768 in New York City,” New York History 95, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 156.

[13]Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution Vol. 2 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1852), 805.

[14]Washington Irving, Life of George Washington Vol. 2 (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1860), 240.

2 Comments

Mr. Muchowski,

As an enthusiastic reader of JAR, I found your article to be very informative and, for me, it connected so many dots.

If I may, however, I’d like to add that William Smith, Jr.’s legacy was that he remained loyal to the crown by refusing to sign a pledge of allegiance to the American cause and was appointed Chief Magistrate of New York and counselor to General Henry Clinton during the revolution. Ref. “Major John Andre’ – A Gallant in Spy’s Clothing” by Robert Hatch and Secret History of the American Revolution” by Carl Van Doren.

William Smith Jr. eventually became Chief Justice of Nova Scotia.

William Smith Jr.’s brother, Joshua Hett Smith was Major Andre’s cohort in the Arnold treachery of 1780.

Respectfully,

Roy Voltmer

Roy, thank you for the thoughtful response. I’m glad you found the article informative and appreciate the information regarding the Van Doren book and the career of William Smith Jr. It’s a fascinating and very much understudied story.

Be well,

Keith