Col. Abraham Buford is most famous for his defeat at Waxhaws, South Carolina, on May 29, 1780. His defiant message to Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, his order for his men to hold their fire until it was too late, and the subsequent chaos and bloodshed that was later called the Waxhaws Massacre is well-known. What is not well-known is that even after Waxhaws, Colonel Buford rallied his survivors and continued to lead them in the field for another seven months. His command was filled with Continental Line and State Line veterans, new levies, substitutes, deserters, and drafted men to create “Buford’s Battalion,” sometimes called “Buford’s Regiment.” The battalion is often forgotten in the history of the Southern Campaign, despite over 100 veterans who were present at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and played an important role in the engagement.

Following the defeat at Waxhaws, Buford marched his survivors to Hillsborough, North Carolina. There Buford gathered about one hundred men of his old command. Some joined Lt. Col. Charles Porterfield’s Virginia State Detachment command and continued to serve with him for the next few months.[1] Maj. Gen. Johann de Kalb arrived in early June with the Maryland Division and assumed command of the new Southern Army at Hillsborough. Gen. Johann de Kalb reported that Buford’s men were mostly without arms and proper clothing, so on June 11 he permitted Colonel Buford to return to Virginia to refit and fill the ranks of his disorganized battalion.[2] Buford promised General de Kalb the newly reorganized battalion would return by the beginning of July.[3]

The difficultly in understanding Virginia Continental troops after the fall of Charleston is the plan that was made to reorganize the Virginia regiments versus what happened in reality. On July 18, 1780, Gen. Washington instructed Brig. Gen. Peter Muhlenberg on how the Virginia Line should be organized. The new Virginia Line would consist of seven regiments, designated the 2nd, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th Virginia Regiments. The Virginia General Assembly had passed a bill to recruit 5,000 men for the Continental Army, and if these new recruits could not be gathered all at once, Washington trusted Muhlenberg to pick a central location to gather them and fill each regiment to 504 rank and file, starting with the 2nd Virginia and then filling the next regiment.[4] The veterans of other regiments who were not included in the reorganization were to be transferred equally to the other seven regiments. Washington finished the letter by reminding him, as well as the other officers of the Virginia Line that “The crisis is a most interesting One — and on your and their exertions, and the discipline and bravery of the Troops, great and early events may much depend.”[5] The reality was that this plan was never executed. The dire situation in the Carolinas, followed by the campaigns of 1781 in the South and in Virginia necessitated troops being sent quickly into the field and no formal organization took place. The history of Colonel Buford’s Battalion is an example of the disorganization.

Colonel Buford arrived in Petersburg in late June to find everything in confusion. General Muhlenberg had assumed command of the Continental forces in Virginia including recruiting. His battalion’s strength was augmented by two companies of Continentals that had been left behind in Virginia by Buford in the spring, led by Capt. Thomas Bowyer of the 8th Virginia and Capt. Thomas Bell of Gist’s Additional Regiment. The remainder of the Waxhaws survivors were spread over other companies. Buford had promised to return by the beginning of July, but most of the supplies and arms that were in Virginia had already been sent south. General Muhlenberg found that Virginia now had to supply for the Virginia Line, as well as the Virginia State troops and the militia being organized to go south. Because of this, Buford was delayed in marching until mid-August at the earliest. On June 27, 1780, Gov. Thomas Jefferson was advised to outfit all the troops in priority of service, with Colonel Buford’s Battalion and any about to serve in the South to receive preference.[6]

On July 21, 1780, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, who had just assumed command of the Southern Army, wrote to Governor Jefferson and ordered that the “remains” of Buford’s Battalion, along with the men of the 1st Virginia State Regiment, march south as soon as possible to join his forces to retake South Carolina. The 1st and 2nd Virginia State Regiments had arrived back at Virginia the previous winter after serving with General Washington. As state troops, they were not raised to serve outside of the state unless ordered to by the governor or general assembly, but losses in 1777 had necessitated their service out of their home state. Many had been discharged over the spring as their enlistments had expired, and they now numbered no more than 300 officers and men combined. Neither the state regiments nor Buford’s Battalion were in any shape to go south, as they all lacked proper muskets, tents, uniforms, and blankets. Gates wrote that “no objection can arise in complying with this order” unless it dealt with clothing and arms, which Gates wrongly assumed the State of Virginia was prepared for.[7] Clothing was promised to the Virginia troops; the Clothier Department had been ordered by Governor Jefferson to have all state and continental troops issued hunting shirts instead of coats.[8]

The ranks of Buford’s Battalion were filled with old soldiers rather quickly. On August 1, 1780, General Muhlenberg reported to General Washington that he had collected five companies of sixty “old soldiers” each, organized into the battalion under Colonel Buford.[9] In addition to the 300 veteran soldiers, most of the paroled prisoners from Waxhaws had reported to General Muhlenberg at Chesterfield Courthouse, Virginia. The most senior company officers were placed in charge of the veterans and new recruits. Buford’s Battalion, as well as the State Troops, had been issued new hunting shirts in early August and were issued new muskets shortly afterwards.[10] The 1st Virginia State Regiment only waited for pay to march south, while the 2nd Virginia State Regiment’s march was halted due to disputes among their officers, in addition to the regiment only consisting of thirty rank and file. Despite being uniformed and armed, Colonel Buford’s Battalion did not march out of Chesterfield Courthouse until August 24 because they did not receive knapsacks and blankets until that time.[11]

Buford marched out of Chesterfield Courthouse with a mixture men in the battalion. Included were survivors of Waxhaws, old soldiers of the Virginia Line, and companies from the 1st Virginia State Regiment. After only eight months out of Continental service, the 1st Virginia State Regiment was again in Continental service.[12] General Muhlenberg reported to General Washington on August 24 that he had sent a battalion of 300 comprised of “old soldiers—recruits—& deserters.”[13] The battalion passed through Granville, North Carolina, on September 6, where Judge John Williams wrote to North Carolina Gov. Abner Nash that the men were “very well armed.”[14] Colonel Buford arrived in General Gates’ camp near Hillsborough, North Carolina, on September 9 and reported that the battalion had 250 officers and men fit for duty out of the 287 who marched with him from Petersburg, divided between seven companies.[15] Buford’s subordinate was Maj. Thomas Ridley of the 6th Virginia and a veteran of four years. The battalion consisted of seven companies as of September 9.[16] Buford was also joined by Lt. Col. John Webb with another 300 Virginia Continentals.[17] Other officers soon joined the battalion, including Capt. Andrew Wallace of the 8th Virginia. Capt. Thomas Bell later joined the Virginians at Hillsborough, as did several other officers of the Virginia Line. The difficulty in understanding which officers (as well as which men) were present is that there are few surviving returns; the known names are collected from letters, reports, and the pension applications of 234 veterans. It appears that the officers were moved around between the companies or with troops back in Virginia. Lt. Epaphroditus Rudder of the 1st Virginia State Regiment is one example. He was in command of a company in Buford’s Battalion in September 1780, but by November 1780 he is remembered by veteran James F. Hudgins as “engaged in enlisting soldiers for the Regular Army” in Petersburg, Virginia.[18] Rudder was listed as serving in the 1st Continental Light Dragoons the following year.

General Muhlenberg reported to Washington that he sent Buford’s Battalion properly armed and with knapsacks and blankets. General Gates, however, was astonished that Colonel Buford’s Battalion arrived with no tents. “Sickness, Death, and Desertion,” Gates wrote to Jefferson on September 9, “must certainly be the dire result sending Troops into the field at the antimoral equinox unfurnished with so essential an article.”[19] They were soon replaced by new levies that arrived at Hillsborough. On July 12, 1780, the Virginia General Assembly passed a new recruiting law which authorized 3,000 men to be recruited for eighteen months. Each county was ordered to fill a quota equal to one-fifteenth of their respective militia. If they failed to fill their quota within about two months, then a draft would take place. Starting in September, counties began to send portions of their quotas (if they met them) and due to a lack of supplies, as well as proper orders, some marched directly to Hillsborough to join Colonel Buford. On October 5, Lt. Ballard Smith marched into camp near Hillsborough with forty recruits from Botetourt County. The recruits arrived “in a manner naked” as General Gates reported to General Muhlenberg and “intirely unsupported with a Single Article a Soldier ought to possess.” Gates requested that Governor Jefferson “not send any men into the field, or even to this camp, that are not sufficiently clad, well furnish’d with Shoes, Blankets, and every necessary for immediate service.”[20]

The men of Buford’s Battalion were a mixture of veterans, volunteers, drafted men, and substitutes. Based off the surviving veterans, the average age for the enlisted soldiers was twenty-three years old, with a range between fifteen and fifty-two years. The average soldier in the Battalion had at least two years of military service before 1780, with some having been in service since the beginning of the Revolution. Two of the companies came from the 1st Virginia State Regiment in September 1780, and were comprised of mostly men enlisted for the duration of the war with three years of experience. Around three-fourth of the sergeants in the entire Battalion were veterans. Sgt. John Porter had served two years in the 5th Virginia Regiment, then again for six months with the Virginia Militia and had fought at the Battle of Stono Ferry, South Carolina in 1779. Pvt. James Bridget was a veteran of the 10th Virginia and had survived the disaster at Waxhaws.[21] Pvt. William Jewell still bore the scars of Waxhaws with sword and bayonet wounds on his arm, chest, and head as well as a missing thumb. He joined the battalion later in the fall of 1780 after escaping from the British at Charleston.[22] Most of the veterans of the 1st Virginia State Regiment had fought at the Battles of White Marsh and Monmouth, as well as Stony Point and Paulus Hook.

Other soldiers had joined with little to no military experience. Sgt. William Chandley of Capt. Bell’s Company was a twenty-five year-old Irishman who had joined the Virginia Line after running away from his employer in New York.[23] John Bullard had escaped imprisonment after he was captured at the Battle of Camden while in the militia and enlisted in Capt. Thomas W. Ewell’s Company of 1st Virginia State Regiment.[24] Others found themselves forced into service. William Williams was twenty-three years old when he was drafted from his home county of Botetourt and attached to Captain Bowyer’s Company. John Guise enlisted as a substitute for his brother Philip and the nineteen-year-old left his family from Rockingham County to serve eighteen months.[25] By December 1780, about 500 Virginia Continentals had been sent to join Colonel Buford’s Battalion in North Carolina.[26]

While more levies were brought into the camp of Buford’s Battalion in October, another familiar face of the Virginia Line joined the Southern Army. Col. Daniel Morgan, the rifleman who had gained fame commanding troops during the Saratoga Campaign, arrived on October 2; he was promoted to brigadier general on October 13. Morgan came at the request of General Gates to take command of the light infantry of the Southern Army. He organized a force consisting of men from the remnants of the Maryland Line, the remainder of the Delaware Regiment under Capt. Robert Kirkwood, and Virginians from Buford’s Battalion. The light infantry corps was divided into five companies: three from Maryland, one from Delaware, and one from Virginia. Capt. Peter Bryan Bruin, a veteran officer who had served with Morgan since 1775, was appointed to command of the Virginia Company.[27] Bryan picked the most experienced and best suited men from Buford’s Battalion to serve in the light infantry. Most of the men selected were veterans, and Bruin also appeared to have a bias for finding men from the Shenandoah Valley or Blue Ridge Mountain regions of Virginia. At least eleven soldiers who had fought at Waxhaws were selected by Captain Bruin to join the light infantry; some accounts claim that there may have been more.[28] Captain Bruin was recalled to Virginia to take command of troops there in November, and Capt. Andrew Wallace was selected to command the company. This light infantry company would fight at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781.

While Wallace and his men marched with General Morgan, Colonel Buford and the rest of the battalion marched with General Gates until he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene in December 1780. Buford became very annoyed as men were continuously pulled from his command to join the light infantry or other commands, and requested leave in October to return home until a regiment could be raised that would be totally his. General Gates refused the request. The detachment of Wallace’s men, illness, desertion, and more companies pulled to reinforce Brig. Gen. Edward Steven’s command, Colonel Buford was left with three companies by November 1780.[29] He had marched with a detachment of 207 Virginia Continentals along with the Maryland Line from Hillsborough on November 10, toward Charlotte, North Carolina. 293 Virginians, mostly the “Eighteen-month men” were left to be collected at Hillsborough by General Stevens.[30] Major Ridley marched the eighteen-month men from Hillsborough eight days later, despite their condition being a “deplorable one” and only able to march after receiving some articles of clothing.[31] Major Ridley wrote to General Stevens that the majority of the eighteen month men were without shoes and didn’t want to march on until they received new ones. Ridley finally received shoes from New Bern and marched 250 men to join Colonel Buford on November 17.[32]

The condition of the men of Buford’s Battalion was best described by Moses Rollins. Moses was seventeen years old when he left his parents and nine siblings in Culpeper County, Virginia, and enlisted for the duration of the war. He marched with Lt. Ballard Smith to Hillsborough to join General Gates’ Army. Rollins joined the army with “only one suit of half worn clothes” with only one shirt and no blanket; in this condition he “did his duty as a soldier.”[33] Colonel Buford received new brown regimental coats to issue to his men. In addition, each man received a shirt made by the ladies of Baltimore, Maryland shortly after the victory at Cowpens.[34]

By January 1781, however, Colonel Buford was no longer with his command. Illness had taken its toll on him and he was sent to gather supplies in Salisbury, North Carolina. He returned to Virginia the following month and continued in an administrative position there for the remainder of the war. Maj. Thomas Ridley assumed command of the battalion.[35] Those who remained in Buford’s Battalion with Ridley in 1781 marched with General Greene during the “Race to the Dan” and finally received new blue short jackets in February 1781. Buford’s Battalion was not the only battalion of Virginians in the Southern Army. Col. John Green of the 6th Virginia marched from Virginia with 400 Continentals in December 1780, and Lt. Col. Richard Campbell led another 400-man battalion from Chesterfield Courthouse in February 1781. The Virginians were organized into one brigade led by Brig. Gen. Isaac Huger.

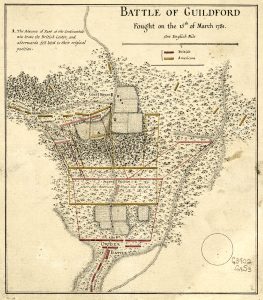

At the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781, Major Ridley led the battalion alongside Col. John Green’s battalion.[36] It is hard to say where exactly Colonel Buford’s Battalion fought on the battlefield. Most certainly they were on the third line with the rest of the Virginia Brigade, but they are often not mentioned on maps depicting the battle nor in the reports. Despite this, the veterans themselves remembered the battle. A total of 111 officers and men who served in Buford’s Battalion either stated after the Revolution their involvement in the battle, or other records indicate they were present in five companies. The companies were commanded by Capt. Thomas W. Ewell, Capt. Thomas Bowyer, Lt. Hezekiah Morton (who was wounded), Lt. Reuben Long, and Lt. Robert Jouett. Sgt. John Bullard of Captain Ewell’s Company (who was wounded in the battle) reported that Major Ridley was still in command of the battalion when they arrived at Guilford Courthouse. Sgt. William Chandley of Captain Bell’s Company stated the same and that he served under Colonel Green at the same time.[37] Pvt. Edward Moody of Captain Ewell’s Company remembered that he fired eighteen rounds during the battle.[38] Pvt. James Bridget, a veteran of five years serving under Captain Bowyer, was disabled when a musket ball broke his right leg.[39] Pvt. Philip Wolfenbarger of Shenandoah County, Virginia, stated that he fought at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and remembered that Major Ridley was in command during the battle.[40] With Buford’s men most likely serving under Col. John Green, they were then part of the rear guard as Colonel Green and his Virginians were the last unit to get off in good order from the battlefield when General Greene ordered a retreat.

In addition to those fighting on the third line near the Courthouse, some of the men of Buford’s Battalion fought in two different light infantry companies. The first company was led by Capt. Andrew Wallace, and he commanded about fifty to sixty men. His company occupied the extreme left of the American first line, with the light infantry of Lee’s Legion on their right (roughly 120 men), followed by Col. William Campbell’s Virginia riflemen (roughly eighty men).[41] Once the first line broke, Wallace and his men fell back toward the southern portion of the battlefield. Engaged in a “battle within a battle,” the Virginians of Wallace and Campbell, alongside Lee’s Legion, engaged with the British 1st Battalion of Guards, the Regiment von Bose, and Tarleton’s British Legion. Eventually they were forced to withdraw, with Captain Wallace killed (the third Wallace brother to die in service during the Revolution), accounts claim their action lasted even after the rest of Greene’s infantry withdrew from the Courthouse area.

On the right flank of the second line fought the other company of light infantry, commanded by Lt. Philip Huffman. Very little information on Huffman can be found before he was commissioned an ensign in the 8th Virginia in the spring of 1777. He was captured at Germantown later that year but escaped in the spring of 1778.[42] He was left in Virginia in the spring of 1780 and led a detachment of recruits to join Colonel Buford’s Battalion that fall. At the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, his light infantry company had been formed recently from men from Buford’s Battalion as well as Colonel Green’s Battalion.[43] Huffman and his men operated with Captain Kirkwood’s Delaware Continentals as what was termed “Colonel Washington’s Light Infantry,” because they served directly under Col. William Washington of the 3rd Continental Light Dragoons. When the first line broke, they fell back to the right flank of the second line in a similar manner to Wallace’s men. They principally fought against the light infantry of the Guards and the Jägers, and fought alongside the Virginia riflemen led by Col. Charles Lynch. Sgt. Maj. William Seymour of the Delaware Regiment remembered that the light infantry of Huffman and Kirkwood fought “with almost incredible bravery.”[44] They were again forced back to the third line where they fought alongside the rest of the Virginians under General Huger, but Huffman was not with them. He had been killed shortly after the fighting began on the second line. Of the 111 officers and men known to have been present at the battle, twenty-two were killed, wounded, or captured.

Almost three weeks after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Colonel Buford’s Battalion ceased to exist. On April 4, 1781, General Greene ordered that Brigadier General Huger, Lieutenant Colonel Campbell, and Lieutenant Colonel Hawes “form the several detachments of Virginia troops into two Regiments of Eight Companies each.”[45] Major Ridley and those who remained of Colonel Buford’s Battalion were consolidated with the companies of Colonel Green’s Battalion and became the 1st Virginia Regiment under Lieut. Col. Richard Campbell.[46] The State Line officers, such as Captain Ewell, were sent back to Virginia with some of the men to join the new 1st Virginia State Regiment, while many of the men were taken by Continental officers. Major Ridley had been placed a supernumerary officer but at the request of General Greene, he remained with the Virginia Brigade until he retired on May 30, 1781. The last official mention of Buford’s Battalion is seen in a court martial held on May 13, 1781, while the Southern Army marched through South Carolina. “John Blackburn of Colo. Buford’s Regiment” was tried for “desertion, joining the enemy, and bearing arms against the United States.” Blackburn plead guilty to desertion, but not guilty to the rest. The court found him guilty and Blackburn was hung alongside two other deserters from the Maryland Line on May 19.[47]

Though the battalion had been disbanded, the service for the soldiers was not yet over. Some of the men were sent back to Virginia to guard supplies or prisoners and were attached to Lt. Col. Thomas Gaskins’ Battalion which fought in the Siege of Yorktown. The majority of the soldiers remained with General Greene and fought in the Virginia Brigade at Hobkirks Hill, Ninety-Six, and Eutaw Springs. Many of the men were placed under Lt. Reuben Long and served as light infantry under Lt. Col. William Washington. All those who had enlisted or had been drafted for eighteen months were discharged at Salisbury, North Carolina, in January 1782, where Maj. Smith Snead had the final command; he wrote to Greene that he discharged them there as they lacked shoes, breeches, and blankets, and he didn’t believe they would make a march as a unit. The discharged veterans made their way home the best they could, with some not reaching home until three or four months later. Those who had enlisted for longer terms were left in South Carolina under Lt. Ballard Smith, who commanded them as light infantry until they were merged with Lt. Col. Thomas Posey’s Virginia Battalion in August 1782. These veterans did not return to Virginia until June 1783 when they were discharged at Richmond, Virginia.

[1]Asher Crockett Pension, W2533, Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters, revwarapps.com (SCAR Pensions and Rosters).

[2]Enclosure: Johann Kalb to the Board of War, June 20, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-26-02-0347-0002.

[3]Horatio Gates to Abraham Buford. -07-20, 1780. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Library of Congress.

[4]George Washington to Peter Muhlenberg, July 18, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-27-02-0147.

[6]Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia Vol. II, ed. H. R. McIlwaine (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1931), 261.

[7]Horatio Gates to Thomas Jefferson, July 21, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-03-02-0579.

[8]Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia Vol. II, 267.

[9]Muhlenberg to Washington, August 1, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-27-02-0344.

[10]Jefferson to Gates, August 4, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-03-02-060.

[11]David Jameson to James Madison, August 30, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-02-02-0047; Henry A. Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army (Philadelphia, PA: Carey and Hart 1849), 200.

[12]Jefferson to George Gibson, August 14, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-03-02-0637.

[13]Muhlenberg to Washington, August 24, 1780,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-27-02-0571.

[14]John Williams to Abner Nash, September 7, 1780, The State Records of North Carolina, Volume 15 (Goldsboro, NC: Nash Brothers Book and Job Printers, 1898), 77.

[15]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Abraham Buford, September 9, Weekly Return on Troop Strength. September 9, 1780. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Library of Congress.

[17]Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg, 202.

[18]James F. Hudgins Pension, S8740, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[19]Horatio Gates to Thomas Jefferson, September 9, 1780, Manuscript/Mixed Material. Library of Congress.

[20]Gates to Jefferson, October 6, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0017.

[21]James Bridget Pension, S39208, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[22]William Jewell Pension, W11946, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[23]William Chandley Pension, W5027, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[24]John Bullard Pension, S3103, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[25]John Guise Pension, W4686, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[26]Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron Steuben to Washington, May 23, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-05847.

[27]Peter Bryan Bruin Pension, S42092, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[28]Research complied by author.

[29]Abraham Buford to Gates, November 1, 1780, State Records of North Carolina, Volume 14, 722.

[30]Edward Stevens to Jefferson, 10 November 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0135.

[31]Stevens to Jefferson, 18 November 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0153.

[32]Stevens to Gates, November 16, 1780, State Records of North Carolina,Volume 14, 738.

[33]Moses Rollins Pension, W10241, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[34]Abraham Hamman Pension, W10088, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[35]John Bullard Pension; United States Congress. House. Committee On Revolutionary Claims. John McDowell-legal representatives of … Report. (Washington, DC: Government printing office, 1858), www.loc.gov/item/tmp92002582/.

[36]Edward Greenelsh Pension, S5209, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[37]John Bullard Pension; William Chandley Pension, W5027, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[38]Edward Moody Pension, W2156, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[39]James Bridget Pension, S39208, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[40]Philip Wolfenbarger Pension, W6575, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[41]Lawrence E. Babits and Joshua B. Howard, Long, Obstinate, and Bloody; the Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 221.

[42]Revolutionary War Service Records, Fold3.com.

[43]John Guise Pension, W4686, SCAR Pensions and Rosters.

[44]“A Journal of the Southern Expedition, 1780-1783,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography,Vol. VII (1883), 378.

[45]Orders, April 4, 1781, Orderly Book of Nathanael Greene, 1781, Apr. 1 – July 25. Manuscripts, Huntington Digital Library.

[46]It was also referred to as the “1st Virginia Detachment” when the eighteen-month men were discharged in January 1782.

[47]Orders, May 18, 1781, Orderly Book of Nathanael Greene, 1781, Apr. 1 – July 25.

3 Comments

Great job with this, John! Valuable research on a confusing period.

John, I’ll echo Gabe’s comments. Excellent research, nice detail and analysis.

Great article. Explains a lot of the post-Waxhaws restructuring. It helped fill an information gap regarding on a specific veteran I’ve been researching. Keep up the good work Mr. Settle!