A lesser-known action during Gen. John Burgoyne’s 1777 campaign occurred at Ticonderoga and Mount Independence in the days surrounding the first battle at Saratoga in mid-September. What became known as “Brown’s Raid” has commonly been interpreted as playing a key role in the defeat of Burgoyne’s invasion. Such is not necessarily the case and, as often happens in war, supplies lie at the heart of the question.

When Burgoyne’s army of British and German regulars, Loyalists, Indians, and Canadians began their move south from Canada in June, they carried with them unresolved supply problems. A large portion of their provisions and stores had to come from England and the ships carrying them had not arrived before the army set out.[1] To augment the army’s supplies until those from England arrived, Burgoyne relied on the success of two assumptions—that his army would receive significant support from Loyalists encountered during the advance and, that his men would be able to forage for the remainder of their needs. The slightest disruption in these assumptions would create serious problems.

Burgoyne experienced much more than a slight disruption: the Loyalist support he counted on never materialized, and the enemy retreating before his army took with them every useful item they could carry and destroyed the rest. By early August, Burgoyne had realized his assumptions had not been well-founded and it would not be long before provisions would start to run low. His army still had over thirty miles to go to reach their objective and, while the enemy had not put up prolonged resistance so far, their numbers had begun to grow and they had established a line of defenses at the junction of the Mohawk River with the Hudson. The fighting over those last few miles would be the toughest of the campaign. Moreover, time threatened to run out. Much of the summer had been cold and wet and the possibility of raw autumn weather arriving early hovered over the army.

To complicate the situation, even though adequate supplies may have been in Canada or even a hundred miles closer at Ticonderoga, Burgoyne did not have the ability to quickly get them to his army. From the outset, Burgoyne had experienced a shortage of carts, wagons, bateaus, oxen, horses, and even harnesses with which to move provisions and stores. By August, with a largely worn-out transport system, the army could move, at best, only four days of provisions per day: at worst, only one. And, that did not include moving any other stores of all types—most importantly, ammunition.[2] Burgoyne needed to find another source of supplies, horses, and oxen or face a brow-wrinkling decision on whether or not to continue the advance.

Possible salvation arrived in the form of information about a large quantity of supplies and cattle in Bennington, Vermont, a few miles to the east. Seizing the opportunity, Burgoyne sent 1,400 German troops in two detachments to capture them. On August 16, around 2,500 American troops routed both detachments, killing over 200 and taking 700 prisoners. In spite of dwindling provisions and stores, Burgoyne decided to continue on.

Already sixty miles from his primary magazine at Ticonderoga, Burgoyne knew that moving forward meant supplies would not be able to reach his army in a timely manner. To rectify the situation, he delayed his advance and began to move all the necessary provisions and stores from Ticonderoga south to be carried with his army.

It took a month to transport everything the army needed from Ticonderoga to Fort George on the south end of Lake George, then to Fort Edward on the Hudson, and finally to the army encamped on the east bank of the Hudson River near the confluence with the Batten Kill. On September 13, with the goods finally on hand, the army broke camp and crossed to the west side of the Hudson. Burgoyne had his men dismantle the bridge and the army resumed its advance. A month later, Burgoyne and his now-disheveled soldiers would return to the same place to lay down their arms in surrender.

The forces opposing Burgoyne’s advance also knew of his supply problems and his long, tenuous line of communications and supply to the north. Around the time of the Bennington battle, the Americans devised a plan to attack the key to that line, Fort Ticonderoga, in a manner that “will most annoy, divide, and distract the enemy.”[3] Rather than capturing the fort, the Americans looked to destroy supplies, wagons, carts, and shipping and force Burgoyne into detaching troops to protect his connection to the north. In essence, do anything that would weaken Burgoyne’s army.

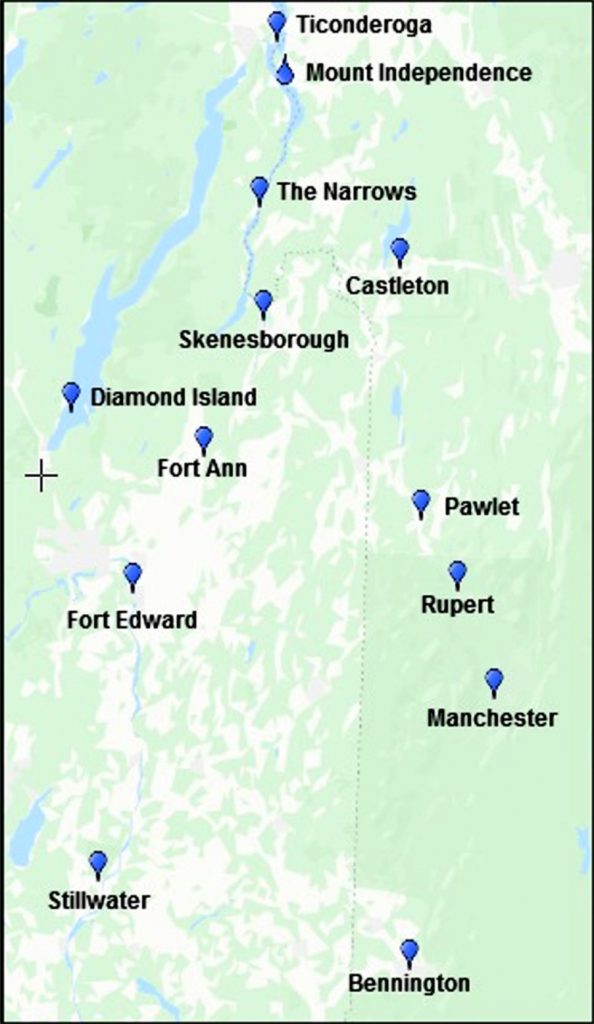

The heart of the plan consisted of three detachments under the overall command of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln.[4] One detachment led by Col. Benjamin Woodbridge would attack the post at Skenesborough on the south end of the extension of Lake Champlain commonly called “The River.” A second detachment commanded by Col. Samuel Johnson would attack Mount Independence on the east side of The River opposite Ticonderoga. With the first two elements serving as support and diversions, Col. John Brown’s third detachment would attack the positions surrounding Ticonderoga. Gen. Jonathan Warner, who joined Johnson after the initial attacks, took overall command of affairs at the Mount and Ticonderoga.

Opposing these parties, British Gen. Henry Watson Powell commanded a garrison of 1,000 men.[5] The majority came from the British 53rd Regiment and the German Prinz Freidrich Regiment with the remainder made up of men from the artillery, navy, Canadian artificers and laborers, and sick and wounded in the hospitals.

In early September, Lincoln began to gather his troops around Bennington, Vermont. They then moved forty miles north to the final staging point in Pawlet where around 2,000 men made camp in the fields surrounding the town. The three 500-man detachments set out on September 12.

The first to reach his objective, Colonel Woodbridge found Skenesborough abandoned and prepared to assist Brown and Johnson as they retired following their raids. The real action started on September 18. Colonel Brown attacked positions around Ticonderoga that morning and, encountering minimal resistance, his men succeeded in overrunning most of the defenses including the battery on top of Sugar Hill (Mt. Defiance). They did not attempt an attack on the fort itself, only demanded its surrender which Powell promptly refused. Colonel Johnson struck at Mount Independence and drove in the pickets but did not attempt a direct attack on the Mount’s formidable defenses.

Brown and Johnson remained in place surrounding the enemy positions and sporadically fired on them for three more days. With no orders to capture the fort or Mount Independence, and lacking siege capabilities, Warner and Johnson retreated overland back to Pawlet and Brown took his forces up Lake George.[6] On the way, Brown attempted an attack on Diamond Island on the south end of the lake where the British had stored some supplies. Warned of the coming attack by an escaped prisoner, the island’s garrison beat back Brown’s forces. The attack a failure, Brown’s men landed on the east side of the lake, burned what plunder they couldn’t carry, and retired back to Pawlet.[7]

The raid had some significant results. Brown had captured nearly all of Ticonderoga’s outworks, 330 of the enemy, over 200 bateaus and other boats, several cannon, and hundreds of small arms along with some ammunition, numerous carriages, harnesses, cattle, horses, clothing, and other stores. They also freed and armed 118 prisoners (many from July’s battle at Hubbardton). Brown’s men sent the captives south to prisons, destroyed the carriages, harnesses, and boats, killed or released the animals, and took with them a considerable amount of supplies while burning the rest. Johnson’s detachment had helped bottle up the garrison and Woodbridge at Skenesborough controlled any passage on The River.

Based on the results outlined above, it would seem the raid’s goal and objectives had been met—they certainly had from the American perspective. Even from the perspective of the Crown forces at Ticonderoga, it would seem the attackers had done what they set out to do. Braunschweig Lt. August Wilhelm Du Roi wrote, “Not only was the transportation of supplies to our army very difficult on account of the attacks made by the enemy, but all communication between our armies was cut off.”[8] Further, with Woodbridge in control of Skenesborough and Brown’s men destroying most of the boats on Lake George, reinforcements could not move beyond Ticonderoga. Even if the route south opened up, most of the carts and harnesses necessary to transport supplies had been destroyed in the raid.[9] Leaving Burgoyne with dwindling provisions and stores and no replacements for casualties and desertions, it would seem Brown’s Raid, coming right at the time Burgoyne’s army needed provisions, stores, and troops the most, seriously impacted Burgoyne’s campaign.

However, the question of whether or not Burgoyne’s line of communications had been severed cannot be conclusively answered by looking at it through the American perspective or even the perspective of the Crown forces at Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. The answer can only be found by looking at it through the eyes of Burgoyne and his men.

Several pieces of evidence point to a different conclusion. Perhaps the most significant factor that seems to be overlooked by many historians is the timeline of events. Brown’s and Johnson’s men attacked their respective objectives on September 18 and, it is claimed, cut Burgoyne’s line of communication. But by the time of the raid, Burgoyne had already crossed the Hudson and, most importantly, knew that, “from the hour I pass the Hudson’s River and proceed towards Albany, all safety of communication ceases.”[10]

Burgoyne’s decision regarding communications went well beyond mere “safety.” In the inquiry into the campaign before the House of Commons in 1779, Burgoyne and others on the expedition commented on deliberately cutting the line of communications with Ticonderoga and Canada. For example, in his questioning of Capt. John Money, deputy quarter master general of the expedition, Burgoyne asked, “Why did the army remain from the 16th of August to the 13th of September, before they crossed the Hudson’s River to engage the rebels at Stillwater?” Money answered, “To bring forward a sufficient quantity of provisions and artillery, to enable the general to give up his communication[author’s emphasis].” A bit later in his testimony, Money commented on how officers with Burgoyne knew that he chose to move on Stillwater, “under the necessity of giving up his communication.”[11] Another unknown officer wrote in his journal for September 13, “The Bridge from Batten Kill was broken up, and floated down the River, and all communication with Canada voluntarily cut off.”[12]

Burgoyne planned to sever the line of communications—and abandon any posts along that line—long before his army actually crossed the Hudson. In a letter to Lord George Germain dated August 20, Burgoyne wrote that, “To maintain the communication with Fort George during such a movement [crossing the Hudson and going forward], so as to be supplied by daily degrees at a distance, continually increasing, was an obvious impossibility. The army was too weak to have afforded a chain of posts.”[13] By the time Woodbridge’s detachment reached Skenesborough, the British garrison had been long gone. The same can be said for Fort Edward and any other posts along that route. Clearly, Burgoyne had chosen to abandon his ties to the north long before Brown’s Raid had progressed much beyond the planning stage.

But, even if communications had not been voluntarily abandoned, would Brown’s Raid have mattered to Burgoyne’s army? The answer is, probably not. It has already been shown above that Burgoyne took a month to move the necessary provisions and stores out of Ticonderoga and south to his army. That is why Colonel Brown wrote, “There is but a small quantity of provisions at this place.” In addition, what stores Brown found must not have been of much value to either Burgoyne or Brown (largely the army’s personal baggage)—the former left them at Ticonderoga and the latter burned most of what he captured.[14]

What of the reinforcements stalled at Ticonderoga? Even if Brown had not destroyed the transport for their provisions and stores thereby allowing the troops to move on, Powell feared a return by Brown’s force and refused to allow those men to leave. Further, Burgoyne himself explained that those reinforcements actually mattered little: he wrote that they would have arrived “in time to facilitate a retreat, though not in time to assist my advance.”[15] Given that a large number of Gen. Horatio Gates’ army had crossed the Hudson just north of Burgoyne’s camp, even the possibility of retreat is questionable.

There is evidence that Gates, entrenched with his army on Bemis Heights, knew Brown’s Raid would not have any real value: he probably had learned of Burgoyne abandoning his line of communications, thereby voluntarily doing Brown’s work for him. On September 17, with Brown and Johnson still on the march toward their objectives, Gates wrote to Lincoln, “would it not be right, you take some Station near or upon the North [Hudson] River? … your posting Your Army somewhere in the Vicinity of mine [at Stillwater], must be infinitly Advantageous to Both … it would embarrass [Burgoyne] exceedingly.”[16] While Gates certainly intended his words to be taken as orders, the phrasing allowed Lincoln some discretion and he allowed the raid to continue.

On September 19, at the height of the raid and not having received word of Lincoln following his “suggestion,” Gates wrote another letter to Lincoln saying in much sterner language that he ought to be at Stillwater and ordered him to take position with 500 or 600 men on the east side of the Hudson.[17]In hopes to satisfy Gates, Lincoln did send 700 men (late arrivals at Pawlet) that he had intended to reinforce Woodbridge in a drive towards Fort Edward.[18]

Lastly, there is a distinct lack of documentation that the British felt any concern about the Americans attacking Burgoyne’s line of communication. There are occasional vague references to possible American threats such as Burgoyne’s famous comment, “The Hampshire Grants [Vermont] … hangs like a gathering storm upon my left”[19]or his note to Powell, “It is said they [the Americans] are in some force of Militia towards Connecticut with a detachment at Pawlet.”[20]Early in the campaign, this dearth of comments can be attributed to the lack of any viable American forces near Burgoyne. Later, the lack of concern can be attributed to Burgoyne having already severed that link with Ticonderoga.

Brown’s Raid developed at a time when the goal and objectives seemed valuable and attainable. At its inception, should it have been successful, the raid might well have created a serious problem for Burgoyne’s army. But over the weeks between planning and implementation, conditions changed so that the results of the raid had little value. Short on supplies, worn out, wet, and facing an entrenched enemy nearly three times its numbers, Burgoyne’s army would have suffered a defeat regardless of Brown’s activities.

[1]Ironically, Burgoyne had foreseen this very problem in his Thoughts for Conducting the War from the Side of Canada submitted in February, 1777, to Lord George Germain, the secretary of state for the colonies. This report formed the basis for Burgoyne’s invasion just four months later.

[2]Questioning of Captain Money, Deputy Quarter Master General, in Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition From Canada, as Laid Before the House of Commons (London: J. Almon, 1780), 41.

[3]Benjamin Lincoln to John Brown, Pawlet, Vermont, September 12, 1777, Correspondence of the American Revolution, ed. Jared Sparks (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1853), 2:525.

[4]Most of the troops and the senior officers came from Massachusetts militia regiments. Some Vermont militia and Samuel Herrick’s Rangers along with Continentals from Col. Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys and Capt. Benjamin Whitcomb’s Rangers joined them.

[5]Using the eighteenth century maxim of needing one man for every four feet of perimeter to adequately defend a post, Ticonderoga and Mount Independence required around 7,000 men.

[6]Lakes George and Champlain flow north, so moving south on these waterways is going “up” the lakes.

[7]John Brown to Benjamin Lincoln, Skenesborough, September 26, 1777, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, vol. 74 (October, 1920), 289.

[8]August Wilhelm Du Roi, Journal of Du Roi the Elder, trans., Charlotte Epping, Americana Germanica, No. 15 (University of Pennsylvania: 1911), 101.

[9]Allan MacLean to Guy Carleton, Ticonderoga, September 30, 1777, Fort Ticonderoga Bulletin 7, No. 2 (July, 1945), 33.

[10]Burgoyne to Germaine, August 20, A State of the Expedition, xxv-xxvi.

[11]Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, 45.

[12]For Want of a Horse, George G. F. Stanley, ed. (Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada: Tribune Press, 1961), 143.

[13]Burgoyne to Germaine, August 20, A State of the Expedition, xxii.

[14]Brown to Lincoln, Lake George Landing, September 18, 1777, NEHGR, vol. 74 (October, 1920), 286.

[15]Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, 15.

[16]Horatio Gates to Benjamin Lincoln, Bemis Heights, September 17, 1777, The Horatio Gates Papers, 1726-1828, microfilm (Sanford, South Carolina: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1978), 5:659-60.

[17]Gates to Lincoln, Bemis Heights, September 19, 1777, The Horatio Gates Papers, 5:685; “General John Glover’s Letterbook,” Essex Institute Historical Collections, Salem, MA, v112, issue 1 (January 1976), 43.

[18]Lincoln to Gates, Pawlet and Castleton, September 20, 1777, The Horatio Gates Papers, 5:700, 703-4.

[19]Burgoyne to Germaine, August 20, A State of the Expedition, xxv.

[20]Burgoyne to Powell, September 21, 1777, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bad6720b-4728-a00b-e040-e00a18067aa1.

4 Comments

Fascinating analysis! At least, Gen. Lincoln’s failure to follow Gates’ commands and Brown’s raid did no harm. Additionally, Mike, you provide another example of the British strategic inability to attack and control territory beyond the immediate reach of their concentrated armies.

“Brown’s Raid” has commonly been interpreted as playing a key role in the defeat of Burgoyne’s invasion.” It did not impede the impetus of Burgoyne to continue his drive south, however, it did help to increase the aura of isolation. And that if Burgoyne could not go forward, (as Freeman’s Farm demonstrated) he could no longer go backward. At what point did Burgoyne decide he only had two options, go forward or surrender? When did he give up the third option of retiring to Ticonderoga and wintering there? I think that is where Lincoln’s force (and Brown’s raid) had its real impact. It did not defeat Burgoyne, but it enhanced that defeat by elevating it to a catastrophic surrender.

Thank you for this informative article. As a point of clarification, this article by Michael Barbieri refers to Col. John Brown, someone not to be confused with the John Brown that led the attack on the HMS Gaspee in 1772: https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/03/conspiracy-destroy-gaspee/

He was, however, the fellow who was killed at the Battle of Stone Arabia (Mohawk Valley area), October 19, 1780, by a Loyalist-British-Indigenous raiding party under Sir John Johnson.