Pennsylvania settlers of the Susquehanna West Branch Valley endured extreme hardship through the first years of the revolution. The men and supplies they provided the Continental army left the frontier exposed and vulnerable.

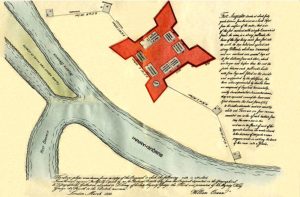

Fort Augusta, a traditional timber star-fort and vestige of the French and Indian War, stood in Sunbury at the confluence of the Susquehanna North and West Branches. The fort anchored the frontier’s defense.

The productive farms of the West Branch quickly became targets of Loyalist and Iroquois raids. With most of the militia away fighting with Washington, some settlers fortified their homes with log stockade walls large enough to provide room for neighbors to shelter inside. There was soon a string of these forts at regular intervals up the West Branch. When an enemy raiding party attacked, or was discovered approaching the valley, settlers grabbed the ammunition, powder and essential supplies they’d readied for a quick departure and headed to the nearest fort. This set a relay in action in which each settler warned their nearest neighbor. Valley residents congregated to the closest fort and waited until the danger passed.

Witness Anna Jackson Hamilton recalled the experience of a typical family. She said,

Upon hearing the signal, the man of the house sprang for his musket, usually kept over the fireplace. The older boys had important duties, each older child to shepherd one of the smaller ones, each to carry blankets, salt and flour . . . the mother to see to it that the baby of the family did not waken and cry out to betray what the family were doing . . . often the valley went to bed in their own cots but the rising sun would find them all assembled in the forts.[1]

Settlers endured a regular series of attacks that saw many killed and many farms and crops destroyed. Meanwhile, the war’s major campaigns continued to siphon ever-more militia and supplies from the valley.

Conditions were particularly dire by the spring of 1778. Northumberland County military leader Col. Samuel Hunter noted on March 28 that there were only two rifles and six muskets in the public stores.[2] Compounding the bleak situation, settlers hadn’t planted that spring since they hadn’t dared to leave the forts. Colonel Hunter further reported on May 31,

We are really in a melancholy situation in this county. The back inhabitants have all evacuated their habitations and assembled in different places. . . . The people in general are so discouraged that I am afraid we will not be able to make proper stands against the enemy unless we get more assistance from some other quarter.[3]

Enemy raids increased in frequency and severity through June. Then, news of the Wyoming Massacre reached Colonel Hunter at Fort Augusta. More than five hundred Loyalists and Iroquois attacked the North Branch Wyoming Valley and killed more than three hundred Patriot militia and settlers. This effectively removed all but the barest Patriot defense from the North Branch.

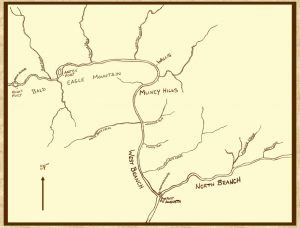

Colonel Hunter knew the West Branch was now even more vulnerable.[4] He sent word to Col. William Hepburn, who was leading a company of militia and local settlers gathered at Wallis’s, just north of present-day Muncy, to evacuate the entire West Branch valley.

Colonel Hepburn immediately began planning for the evacuation. But, he also needed to warn those further upriver. Robert Covenhoven and a young millwright, whose name has been lost, volunteered for the dangerous mission. They had to carry the evacuation orders to the settlers at Antes Fort, near present-day Jersey Shore. This meant they had to travel approximately twenty five miles through a no-man’s land of mostly undefended territory. They were essentially on their own.

Covenhoven knew raiders would stick to the regular valley paths.[5] The least dangerous route would be to travel across the top of Bald Eagle Mountain, which entailed a climb of about fifteen hundred feet, then down and up multiple deep ravines and through thick vegetation. Bald Eagle Mountain began directly across the river from Wallis’s. So, they crossed the river and started their ascent.

Covenhoven and the young millwright reached Antes Fort that evening. As they dropped down into the valley and approached the fort, they heard a shot. They later learned a young woman who ventured out to milk a cow had been fired upon. She was unharmed but the ball passed through her clothing. The enemy was certainly nearby.

Covenhoven delivered the evacuation order to Col. Henry Antes, who led those gathered at his fortified home. He, in turn, arranged to warn the settlers at Horn’s Fort, another fifteen miles upriver. Meanwhile, the Antes Fort settlers began securing boats to carry the women and children downriver. When those were exhausted, they employed whatever might float and could be pressed into service. They also worked to secure their belongings. They frantically buried whatever they couldn’t carry in places where they thought they could retrieve them, later.

The Horn’s Fort settlers arrived with news they’d been attacked and three of them had been killed. They’d carried the dead men’s bodies with them and buried them at Antes Fort before proceeding.

The settlers launched the women and children off into the river while the men marched with the livestock along the shore. This allowed them to move their precious stock with them while also acting as a buffer between the women and children and any pending attacks. Everyone was jittery after the Horn’s Fort attack and expected more violence at every moment.[6] The tense mood was exacerbated by the mid-summer river exposing shallows and slowing the settler’s anxious progress. The flotilla began regularly grounding along the way. Women routinely jumped off the boats, allowing them to refloat, and then pushed them across the shallows until they got back to deeper water where they could re-embark.

A participant in the evacuation, Mrs. Hannah Miller, described an incident on the way:

they had placed boxes . . . along the sides of the craft, leaving a space in the center where the beds were made for the women and children. While a German woman was engaged doing something about the boat, she laid her baby on one of the boxes. It rolled off and, landing among the other children, commenced crying loudly. This alarmed all the mothers and they had a hard time to prevent their babies from crying. They feared that such a noise might attract the attention of the Indians lurking along the shore.[7]

As they progressed, settlers who’d gathered at forts further downriver joined the procession. Covenhoven described the flotilla as follows, “Boats, canoes, hog-troughs, rafts hastily made of dry sticks, every sort of floating article had been put in requisition and were crowded with women, children and plunder.”[8]

Though deprived of the companies of men off fighting in the army, the valley still held many settlers. The scene of them all evacuating simultaneously was memorable. Anna Jackson Hamilton described it, saying, “You couldn’t possibly count the people. Might as well try to count the raindrops in a cloud.”[9] Actual numbers of those fleeing were probably in the hundreds. Other witnesses told of how the sky at night was red with the flames of the burning farms and grain stores being destroyed by the enemy, behind them.[10]

Most of the locals who evacuated the valley rested briefly at Fort Augusta and then continued on down the river. Colonel Hunter implored militia leaders in Berks County to lend some aid. He wrote,

The inhabitants of the West Branch have suffered almost as much as Wyoming, though not at one time. . . . However, both branches are almost evacuated. . . . From all appearances, the towns of Northumberland and Sunbury will be the frontiers in less than twenty-four hours. The inhabitants of both towns, with a few of the fugitives from the upper parts of this county, seem determined to make a stand. But, how long they can do it is very precarious, and indeed without assistance from other counties their stand will be very short. In which case, you and other counties must experience the calamities we now feel by being the frontier.

Nothing but a firm reliance on Divine Providence and the virtue of our neighbors induces the few to stand that remain in the two towns. . . . If they are not very speedily reinforced they must give way, but will have this consolation, that they have stood in defense of their liberty and country as long as they could.

In justice to the county, I must bear testimony that the States never applied to it in vain. The whole State must know that we have reduced ourselves to our present feeble condition by our readiness to turn out upon all occasions when called upon in defense of the common cause. Should we now fall for want of assistance, let the neighboring counties reconcile to themselves, if they can, the breach of brotherly love, charity and every other virtue which adorns and advances the human species above the brute creation.[11]

The few settlers and militia who remained at Fort Augusta in the aftermath of the Big Runaway did hold. And, reinforcements arrived some tense days later. That laid the groundwork for eventually retaking both branches of the river and the bulk of the county between them. In fact, Fort Augusta became the supply depot for offensive operations that would soon wreak havoc on the enemy. But, for now, the devasted settlers held firm at the most critical moment and preserved the rest of the state from a similar fate.

In a 1959 presentation, Helen Herritt Russell commented on the West Branch settlers’ pivotal role in the revolution saying,

I submit to you that it was the contribution made by the people of the upper West Branch, together with the Northumberland County militia of which they formed a major part, that saved the war for the colonists; because by holding this far-flung line intact for as long as they did, the interior of the state could function in safety—a collapse at any other stage would have spelled disaster, and this they had prevented.[12]

[1]Helen Herritt Russell, “The Great Runaway of 1778,” Northumberland County in the American Revolution(Sunbury, PA: Northumberland County Historical Society, 1975-1976), 87.

[3]John F. Meginness, History of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania(Baltimore: Gateway Press, Inc. 1990 reprint of the original 1892 original,) 128-129.

[4]J. F. Meginness, Otzinachson: A History of the West Branch Valley of the Susquehanna (Baltimore: Gateway Press, Inc. 1991 reprint of the original 1889 edition,) 506.

[5]Meginness, History of Lycoming County, 134.

[8]Everts, Peck and Richards, History of that part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys embraced in the Counties of Mifflin, Juniata, Perry, Union and Snyder in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania(Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc. 1996 reprint of the 1886 original,) 108.

[9]Russell, “The Great Runaway,” 97.

3 Comments

Thanks for this! It was fascinating. Especially enjoyed the first-person descriptions of their experiences (from women!).

Thank you, Catharine! The American Revolution on the West Branch was very much everyone’s struggle. All who lived through the events of the war fought and sacrificed. And, there are many instances of women, there, who made a significant impact on achieving the final victory. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Thank you, Catharine! The American Revolution on the West Branch was very much everyone’s struggle. All who lived through the events of the war fought and sacrificed. And, there are many instances of women, there, who made a significant impact on achieving the final victory. I’m glad you enjoyed it.