Of the roughly nine hundred men who served at some point in the 8th Virginia Regiment in the Revolutionary War, only fifty-two have identified graves. Several of them are marked with wrong information that needs to be corrected. In some cases, the information is dramatically wrong. Sadly, this review of fifty-two grave markers from just one regiment may indicate a significant amount of bad information carved into stone in cemeteries across the eastern half of the United States.[1]

Leonard Cooper had one leg and he didn’t like to tell people why. When he applied for a veteran’s pension in 1818, he more than bent the truth in saying that he was in “a skirmish” at Paramus Meeting House, New Jersey where he “was wounded and lost his leg.”[2] The truth? He lost his leg in a duel with another officer at Pompton Plains in October 1779.[3] Cooper was the lieutenant commandant, or “captain lieutenant,” of Col. John Neville’s company of the 4th Virginia Regiment. This was a new rank for the Continental Army modeled on British practice that resulted from a cost-saving reduction in the number of officers. As the regiment’s senior lieutenant, Cooper led a company nominally under the direct command of the colonel.[4] Perhaps Abraham Kirkpatrick, the man who shot him, thought Cooper was putting on airs.

Whatever his reason, Kirkpatrick was clearly the aggressor. He attacked Cooper with a stick. Cooper apparently had a more peaceful temperament and showed no “disposition to demand satisfaction.” The era’s code of honor, however, required him to make the challenge. His peers could not abide Cooper’s reluctance to stand up for himself and told him that “unless he did, he must leave the Regiment, as they were Determined he should not rank as an Officer.” Cooper reluctantly complied. He and Kirkpatrick faced off with pistols and the hapless lieutenant took a ball of lead to his leg. The limb was amputated and he was transferred to the Corps of Invalids. He was one of the very last men discharged from the army at the end of the war.[5]

Cooper then went home to the Shenandoah Valley, got married, and had several children. Laws against dueling disqualified him from receiving a state or federal pension, but he did receive some bounty land. He was unable to mount a horse in the usual way, so he trained a mare to kneel for him. Even at the age of seventy he was reasonably independent, regularly riding to the county seat at Front Royal for community events such as court days and militia musters. One day in 1821, however, his mare wandered home with an empty saddle, its reins dragging behind her on the dusty road. Cooper’s body was found in the Shenandoah River. The consensus was that the horse had stumbled in the river’s rocky ford, throwing the old and crippled veteran into the current from which he could not escape. It was a sad end to a difficult life.[6]

Nearly three hundred miles to the west, there was another man named Leonard Cooper. He was a man of some note locally, having established a block house on the north bank of the Kanawha River in 1792 for the protection of settlers in what is now known as the Cooper district of Mason County, West Virginia. Daniel Boone once recommended him to Light Horse Harry Lee—then the governor of Virginia—for a militia commission. It is believed that this Cooper came from Maryland and settled there, where the Kanawha River pours into the Ohio, in about 1790. Little more is known about him, but one story recorded in 1891 relates that he and two other men were once ambushed by Indians at the mouth of the Coal River, a tributary of the Kanawha. One or both of the others were killed, but “Maj. Cooper by leaving his horse and fleeing on foot to the mountains managed to escape the fate which had overtaken his less fortunate companions.”[7]

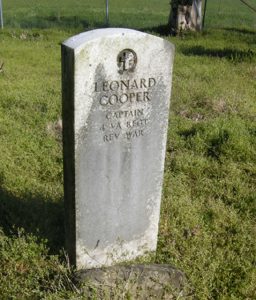

This is not a feat a one-legged veteran of the Continental Army could have accomplished, and yet a stone marker for the 8th Virginia veteran sits atop the sprinting frontiersman’s grave. The marker is set in a small, riverside cemetery ten miles up the Kanawha from Point Pleasant. The government-issued marker reads: “Leonard Cooper, Captain, 4 Va. Regt., Rev War.”[8] No dates are given, but genealogy websites indicate that the man buried there died in 1807—fourteen years before the Continental Army veteran drowned in the Shenandoah.[9]

The Wrong Grave

Someone made a mistake. There is no reason to believe it was anything other than an honest error, though the news that Leonard Cooper of Mason County was never an officer in the 4th Virginia Regiment will certainly be disappointing to some. Captain-Lieutenant Cooper began the war as an ensign in the 8th Virginia Regiment, which was later combined with the 4th Virginia.[10] A survey of known grave markers for Cooper’s comrades reveals that there are at least six erroneously-placed headstones. Others mark the right graves but provide significantly incorrect service data. In every case but one, the errors are made on replacement headstones provided by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or its predecessor agencies. If the mistakes associated with this one regiment are typical, there will be hundreds more to be found in graveyards and cemeteries across many states.

Another marker sits alone in a copse of trees between vacation homes overlooking Lake Sinclair, Georgia. This one reads: “Corp. Drury Jackson, Slaughter’s Co., 8 Va. Regt., Rev. War.” While the Cooper headstone is of the post-World War I design familiar from Arlington and Normandy, this memorial is of the older style common to the graves of Civil War and Spanish American War veterans.[11] It is in a nice spot, but it should be in Virginia.

Drury and Utey Jackson enlisted in Capt. George Slaughter’s Culpeper County company of the 8th Virginia in February of 1776. The oddly-named pair, probably brothers, went south with Col. Peter Muhlenberg under Maj. Gen. Charles Lee to defend Charleston. Both men contracted malaria and Utey died of it on August 20. Drury survived and served out his two-year enlistment. He returned to Virginia and lived the rest of his days there. He applied for a pension in Madison County (which had been created from Culpeper) in 1818 and died in 1835. He seems to have moved over the Blue Ridge to Shenandoah County in his final years and is probably buried there. Though “Drury Jackson” seems like a name unlikely to be conflated, a previous investigation revealed that there were in fact three men with that name living in the southern states at the same time. The body under the stone in Georgia belongs to one of the men who established the “Trans-Oconee Republic” in 1794 in defiance of the federal government. This Drury Jackson was just eight or nine years old and living in what became Tennessee when his namesake in Virginia enlisted in Captain Slaughter’s company at Culpeper.[12]

Several miles to the north in Oglethorpe County, Georgia, there is a marker for “Charles O’Kelley” of the 8th Virginia Regiment. There was no such man, but there was a Charles Kelly in the regiment who belonged to a company raised in faraway Pittsburgh (which was claimed, during the war, by Virginia). The Findagrave.com page for the Georgia grave acknowledges that “Charles service in the 8th Virginia is questionable and no longer supported by the DAR.” Yet the stone remains.[13]

A man named Thomas Newman is buried in Clark County, Ohio and retains what appears to be his original headstone.[14] It reads simply: “Thomas Newman died Aug. 2 1821 in the 72 year of his age.” Flat on the ground below it, however, is a plaque asserting his service in the 8th Virginia. There was a Thomas Newman in the regiment, but he died in the Carolinas at the same time as Utey Jackson.[15] This is confirmed by an affidavit filed by the heirs of his brother pursuant to a rejected pension claim. No other soldiers with the name are recorded as having served in the Virginia Line.[16]

In Corydon, Indiana there is a marker for “John E. Long” of the 8th Virginia who lived from 1755 to 1828.[17]There is only one “John Long” on the 8th Virginia rolls, and he was reported dead on June 1, 1778. He was drafted for a one-year term on February 23 of that year, was reported sick at the Yellow Springs, Pennsylvania military hospital in May, and died there.[18] There do appear to have been other John Longs in the 4th, 6th, and 7th regiments.[19] Images of John E. Long’s original marker show that it made no mention of military service.[20]

Perhaps most jarring is the existence of two graves in different states for the same soldier: Abraham Hornback in Menard County, Illinois and Abraham Hornbeck in Spencer County, Indiana.[21] Hornback enlisted in Capt. Abel Westfall’s company early in 1776 and was picked to be in Capt. James Knox’s company in Morgan’s Rifles in 1777. He consequently participated in very important service at the taking of Gen. John Burgoyne at Saratoga. The Indiana stone, though newer, appears to be the correct one.[22]

John Graves, a junior officer in the 8th Virginia who later served as a captain and major in the Old Dominion’s militia, is also seemingly buried in two places. Graves’ obituary remembered him for guarding Nathanael Greene’s crossing of the Yadkin River during the Race to the Dan and he was present for Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.[23] The erroneous marker is in Boone County, Kentucky.[24] The correct one is in Wilkes County, Georgia.[25]

The Wrong Information

Added to these misattributed gravesites is another category of markers displaying incorrect information about the veterans lying beneath them. Once again, none of these stones appears to be original, though one is quite old. An elegant Shelby County, Kentucky memorial for 8th Virginia Capt. James Knox reads: “Col. James Knox. Was born in Ireland. Came to America at the age of 14 years. Served in the Revolutionary War. Died Dec. 24, 1822, at an advanced age.” The stone is from the middle of the nineteenth century, which is evident from its style and from the minute inscription “J. Falconer, Madison, IA.” Falconer was a stone carver known to be active in Madison, Indiana in the 1840s and 1850s.[26] The stone’s inscription perpetuates an evidently false tradition that Knox immigrated alone as a teenager. Earlier records make it fairly clear that he was in fact born in what is now Bath County, Virginia.[27]

The grave of another captain, later a militia general, lies outside Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Here, like the grave of Thomas Newman, the original headstone remains. It is severely worn and broken into pieces, but has been cemented back together and is upright again. As with Newman, the inscription makes no mention of the decedent’s military service other than his rank title: “To the memory of Gen. William Darke who died November 26th 1801, in the 66th Year of his Age.” A fairly rare original footstone is marked as one would expect with a simple “W.D.” Directly behind the original headstone is an old-style government marker that reads: “Lt. Col. Wm. Darke, 10 Va. Mil. Rev. War.” A 2017 metal plaque provides more biographical detail, including his service as “Captain & Major—8th Regt. Va.” and asserts again that he was “Lieutenant Colonel—10th Regt. Va.” Darke held many positions during his extensive military career. He was both captain and major of the 8th Virginia, but at no time during the Revolution was he in active militia service nor was he ever an officer of the 10th Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line.[28] He did, as a Continental lieutenant colonel, command Virginia militia during the Yorktown campaign. He also held the rank of lieutenant colonel during the 1791 Sinclair Expedition, commanding a regiment of United States levies (six-month federal draftees). The only senior militia command he held after 1775 began in 1792 when Virginia reorganized its militia system. He was appointed a brigadier general, commanding the four regiments from Frederick and Berkeley counties that made up the 16th Brigade.[29] He led these men in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion under (militia) Maj. Gen. Daniel Morgan.[30]

Other 8th Virginia veterans are, like General Darke, wrongly described as militiamen on replacement grave markers. James Range, buried in Carter County, Tennessee, is memorialized in the recessed shield of an old-style government marker as: “Jas. Range, 8th Va. Mil., Rev. War.”[31] Harmon Commins, buried in Anderson County, South Carolina, is remembered on a newer stone as “Harmon Commins, Va. Militia, Revolutionary War, Feb. 1851.”[32]

Dates and battle participation are also sometimes given incorrectly. A family-funded memorial to Arthur Johnson in White County, Illinois, inaccurately credits the veteran with participation in the “Siege of Norfolk” and the Battle of Paoli. It is unlikely that he was at either event.[33] A West Virginia state historic marker next to the grave of William Eagle in Pendleton County states that he enlisted a year before he actually entered the service.[34]

History and Analysis

Veterans’ grave markers are widely trusted to be accurate. There is something about the sanctity of a grave and the power of words carved into stone that elicits deference. The very phrase “carved in stone” has come to describe certainty and finality. Yet this survey of known markers for just one Continental regiment reveals that at least twelve markers have problems ranging from a wrong enlistment date to sitting on the wrong grave entirely. An overview of the history of veterans’ grave markers sheds some light on how this came to be.

About nine hundred men served in the 8th Virginia regiment over the course of its not-quite-three-year career.[35] Marked graves have been identified for fifty-two of them.[36] There were no government programs or patriotic societies to provide headstones when Revolutionary veterans died, and how their graves were originally marked was determined by their families and circumstances. Many families, perhaps a significant majority, could not afford professionally engraved stone memorials. In these cases, wooden markers were often used which rotted within a matter of years. Other veterans were given fieldstone markers with their names and dates scratched into them. The gravestones of Capt. John Stephenson and Lt. Jacob Parret are a higher-end examples of this and survive in Harrison County, Kentucky and Rockingham County, Virginia.[37] All others of this kind are unlikely to be distinguishable from other fieldstones today, though a few may still poke out of the ground in various cemeteries, melancholy in their anonymity.

The first government-provided markers were the responsibility of frontier garrison commanders in the decades before the Civil War. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, “In the course of time, a fairly uniform method of marking burials came into being. A wooden board with a rounded top and bearing a registration number or inscription became the standard. No centralized system for recording burials existed.”[38] This practice continued though the Civil War. After that bloody war ended, the challenge represented by maintenance of hundreds of thousands of wooden markers quickly became apparent. After an extended debate over design (marble versus galvanized iron coated in zinc), the recessed-shield marker design still associated with Civil War graves was introduced in 1873. In 1879, the stones became available for the unmarked graves of veterans—including soldiers of the Revolution—in private cemeteries. The design remained in use with only minor changes into the twentieth century. All government-issued markers for Spanish American War veterans were of this type. A variant with no shield and an angular top was introduced for Confederate veterans in 1906.[39]

After World War I, a new and plainer style of grave marker was introduced for soldiers of that war and later. This “general” design remains the standard for new military graves and is familiar from large national cemeteries. Flat ground markers then became available as well.[40] By this time, known Revolutionary War graves were in a period of stasis. In most cases they either had a durable original or a recently-installed government headstone. An estimate of the balance between these circumstances for 8th Virginia graves can be calculated from the number of old-style markers that have been found. That number is only eight, three of which were marked or placed in error. This suggests that from the 1880s to at least the 1930s there was little need or opportunity to place new markers on Revolutionary graves.[41] Not only were known graves marked, but the locations of most graves that had been unmarked since the deaths of a veteran’s immediately descendants were permanently forgotten. (The exact sites of nearly all wartime burials were never individually marked and were therefore forgotten immediately.) Even Lt. Col. Richard Campbell, a veteran of the 8th Virginia who was Virginia’s second-highest-ranking battlefield casualty after Gen. Hugh Mercer, is buried anonymously somewhere around Eutaw Springs, South Carolina.[42] In all, more than eight hundred 8th Virginia grave sites, about 94 percent of the total, are unknown and unmarked.[43]

While the existence of just five accurately-placed old-style markers shows there was little need for them a century ago, that has changed. Many original stones, especially those made of marble, have now eroded, crumbled and broken. Patriotic societies such as the Sons of the American Revolution and the Daughters of the American Revolution have for decades taken on the task of making sure these graves, too, are not forgotten. The Department of Veterans Affairs will provide a new marker, free of charge, at the request of a descendent. Today, twenty-three out of fifty-two identified graves of 8th Virginia veterans are marked with modern-style government markers, indicating that nearly half of the total have been replaced in the last few decades.

This has coincided with an explosion of genealogical information available on the internet, not all of which is accurate. The 8th Virginia’s 94 percent lost grave rate shows definitively that authoritative information for unmarked graves has always been hard and usually impossible to find. Yet today, easily accessible databases that may identify individuals with the same name, living at the same time, and residing in the same state produce new opportunities for conflation and error. Admittedly, inaccurate information and wishful thinking are not new, as the erroneously-placed old-style markers for Abraham Hornback and Drury Jackson show.

Best-Practice Recommendations

Eight suggestions for more accurately preserving veterans’ graves are made below. No criticism is intended by offering them. The maintenance and replacement of Revolutionary War veterans’ graves is important work for which no one is responsible other than those who volunteer to take up the task. Given that the vast majority of graves have already been lost, these people and the patriotic societies they work with are owed a great deal of gratitude. They almost always do their work accurately and well, especially in the modern era.

Awareness. Descendants, historians, and patriotic societies should be aware that most Revolutionary War headstones are no longer original. (Just fourteen of the fifty-two surveyed here.) Any non-original stone has the potential to contain inaccurate information, particularly in service details. In general, any upright marker that claims military service is probably not original. Original table-style markers with more extensive inscriptions may mention military service, but these are mostly seen at the graves of senior officers such as 8th Virginia colonel (and general) Peter Muhlenberg and Maj. Abraham Kirkpatrick.

More research. Historical research on the Revolution is dominated by the study of events and commanders. Comparatively little work is done at the regiment or company level. This is the sort of granular work that can help identify and avoid mistakes. This article was only possible because of my own focus on the 8th Virginia.

Three checks to confirmation bias. The addition of new service claims to a gravesite is almost always the product of genealogical research. The installation of a new, government-issued marker is often (but not always) done in coordination with patriotic societies. The stones are most often issued by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. While the patriotic societies require proof before conferring membership, they have not always been so discerning about grave markings.[44]The Department of Veterans Affairs appears to issue markers without asking many questions. Descendants, patriotic societies, and the Department should all be strict about documentation and willing to say “no” if a claim is not really proven.

Leave original stones in situ. William Darke’s original headstone, through broken in pieces and cemented back together, remains on site. It is now accompanied by a government marker, perhaps a century old, and a fairly recent metal plaque. The original stone is the only object that contains no errors. It is important to install new markers when the old ones have broken or deteriorated in order to avoid the loss of yet another site. However, whenever possible, the original markers should be left in place even in their damaged condition. In addition to being original-source documents, they are in most cases the only tangible objects that connect us across time with the warriors in the ground. That significance cannot be replaced, only removed.

Use recessed-shield markers. The old-style, recessed-shield markers presumably fell out of use sometime after the last Spanish American War veteran was interred. The Department of Veterans Affairs has made them available again and as originally intended they are the proper style for Revolutionary graves if a government-issued marker is used.[45]The uniformity of the modern-style markers makes a powerful visual impact at Arlington and other national cemeteries. Revolutionary veterans, however, are far more likely to be buried individually in churchyards and isolated family cemeteries. The old-style markers better communicate the antiquity and importance of these sites.

Use granite markers. Government markers are available in both marble and granite. Marble deteriorates far more quickly. It is likely that many graves have been lost because they were marked with marble or sandstone memorials.

Address incorrect markings. Some judgement is required in discerning the best way to do this, according to varied circumstances. Recently-installed markers with incorrect information should simply be removed or replaced. Others may have historic and even instructive value and should be corrected with supplemental objects. The best approach for Drury Jackson’s marker, hundreds of miles from his actual grave, might be to take it home to Virginia and display it on the grounds of the Culpeper County courthouse.

Say thanks. Preserving their graves is one of the few means we have for thanking these long-dead Patriots for their service. We should also thank those who volunteer to do the work. We can do this by providing them with the resources and information they need to get the job done.

A catalogue of known 8th Virginia graves may be seen at 8thvirginia.com.

[1]Thanks to Dale Corey of the Virginia Society, Sons of the American Revolution and Stuart Martin of the Kentucky Society, Sons of the American Revolution, for reviewing this manuscript. The views expressed are mine.

[2]Leonard Cooper pension fileW6712, C. Leon Harris, transc., Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters.

[3]Brig. Gen. James Wood affidavit, Leonard Cooper pension file, Library of Virginia.

[4]Robert K. Wright, Jr. The Continental Army(Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1986), 126-127; Don N. Hagist, “Untangling British Army Ranks,”Journal of the American Revolution, May 19, 2016.

[5]“Leonard Cooper to Virginia Delegates,”June 22, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration; Leonard Cooper pension file.

[6]Hugh E. Naylor letter, July 21, 1932, Edith Cooper Shaver, transc., “The Cooper Papers,” VaGenWeb.org; “Cooper to Virginia Delegates,” n2; Worthington Chauncey Ford et al., eds., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789,34 vols. (Washington, 1904–37), 5:793; William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, 13 vols. (New York: Bartow, 1819–23), 9:38.

[7]Virgil A. Lewis, First Biennial Report of the Department of Archives and History of the State of West Virginia (Charleston, WV: Tribune Printing Co., 1906), 224; Hamill Kenny, West Virginia Place Names (Piedmont, WV: Place Name Press, 1945), 183-184; History of the Great Kanawha Valley, 2 vols (Madison: Brant, Fuller & Co., 1891), 2:36. The rank title “major” presumably refers to position in the county militia. Leonard Cooper of Shenandoah County is unlikely to have ever held the rank of major in any military organization.

[8]“Capt. Leonard Cooper,”Findagrave.com. Line breaks and all-caps are removed and some punctuation altered in this and following marker transcripts.

[9]“Capt. Leonard Cooper,”Findagrave.com.

[10]“Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War” (CSR), National Archives and Records Administration, 959:1236-1308; Leonard Cooper pension file.

[11]“Pre-World War I Era Headstones and Markers,”U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

[12]Drury Jackson pension file S38075, Will Graves, transc., Southern Campaigns; Gabriel Neville, “Stolen Honor in Georgia,”Emerging Revolutionary War Era, May 25, 2020.

[13]“Charles O’Kelley,”Findagrave.com

[14]Thanks to James A. Freeland for bringing this grave to my attention.

[15]CSR, 1050:401-411; James Newman and Thomas Newman pension fileVAS387, Will Graves, transc., Southern Campaigns.

[16]John H. Gwathmey, Historical Register of Virginians in the Revolution (Richmond, 1938, repr. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1973), 583.

[17]“John Edward Long,”Findagrave.com.

[20]“John Edward Long,”Findagrave.com.

[21]“Abraham Hornback,”Findagrave.com; “Abraham Hornbeck,”Findagrave.com. Despite the variant spellings, both markers clearly refer to the same man.

[22]Abraham Hornback pension file W10120, Will Graves, transc., Southern Campaigns.

[23]“Virginia documents pertaining to John Graves,” VAS3751, C. Leon Harris, transc., Southern Campaigns; “John Temple Graves,”Findagrave.com.

[24]“John Graves,”Findagrave.com.

[25]John Temple Graves,”Findagrave.com.

[26]“Eliza Jackson,”Findagrave.com; “Eliza Irvin Bain,”Findagrave.com.

[27]“James Knox,” S. Bassett French biographical sketches, p. 126, Library of Virginia; Joseph Addison Waddell, Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, from 1726 to 1871, 2nd edition (Staunton, Va: C. R. Caldwell, 1902), 320.

[28]Gabriel Neville, “William Darke and George Washington in Politics, Business and War,” Magazine of the Jefferson County Historical Society, 84 (2018): 23-38 (posted at The 8th Virginia Regiment).

[29]“Militia establishment and register of militia commissions of the Virginia Militia, 1792-1796,” Accession 36902, State government records collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

[30]Neville, “William Darke,” 36-37.

[31]“James Range,”Findagrave.com; CSR 1051:345-359.

[32]“Harmon Commins,”Findagrave.com; CSR, 1041:2007-2018; H. Commins pension file S21701, C. Leon Harris, transc., Southern Campaigns.

[33]“Arthur Johnson,”Findagrave.com; CSR, 963:149-201; Gwathmey, Register, 845.

[34]“Eagle Rocks,”Historic Marker Database; Gabriel Neville, “Catching Eagles,”The 8th Virginia Regiment.

[35]Gabriel Neville, “The Soldiers of the 8th Virginia Regiment,”The 8th Virginia Regiment.

[36]Gabriel Neville, “Veterans at Rest: Known Graves, Part One,”The 8th Virginia Regiment.

[37]Gabriel Neville, “Veterans at Rest: Known Graves, Part Two”; “Jacob Perrit,”Findagrave.com

[38]“History of Government Furnished Headstones and Markers,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, cem.va.gov/history/hmhist.asp.

[39]“History of Government Headstones.”

[41]Neville, “Veterans at Rest,” part one.

[42]Gabriel Neville, “Shenandoah Martyr: Richard Campbell at War,”Journal of the American Revolution, December 3, 2019.

[43]Most men from Capt. John Stephenson’s company cannot be identified at all, so some number of additional grave markers may be extant but not identifiable as associated with the 8th Virginia Regiment.

[44]This has improved. The SAR, for example, implemented a new archival resource called the Patriot Research System in 2018 and now requires source documentation accompany requests for burial markings.

[45]“Pre-World War I Era Headstones and Markers,”U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

6 Comments

Excellent research, prime mythbusting. Really well done, I enjoyed reading this one. Great pointers at the end too.

Good job of research and excellent recommendations. My own 8th Virginia ancestor, Joachim Fetzer, is one of the 800+ who have no marker. He is buried in Emmanuel Lutheran Cemetary, Woodstock, Shenandoah County, Virginia.

Great information. Unfortunately most grave sites will never be found. In May 2022 I had a VA marker placed for my 3rd MD SAR ancestor as a cenotaph in Oak Hill WV. He was buried 8 miles away on the ridgeline above his home on upper Loop Creek. Placement was selected next to his son a daughter-in-law. Many other descents are in this cemetery. After submitting the forms, the VA was very helpful and a granite marker was on the way. Unfortunately it was not until the third marker did one arrive undamaged. The funeral home said this was often the case. The VA had a special coordinator who handled this time period. She was referred to as the “old guys” coordinator and was great to work with.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/228200450/benjamin-johnson?_gl=1*13zi543*_ga*MTcyNjA2MDIxMS4xNTU2NjU0NTg3*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*MTY3NjU3NjQ5Mi4xODkuMS4xNjc2NTc4MzI4LjQwLjAuMA..*_ga_B2YGR3SSMB*Y2UzZGNkMDktMmFkYS00OTUzLTgzODYtZTI2OThmNWI4YjM3LjE5Ny4xLjE2NzY1NzgzMjguNDMuMC4w

Bill – If your ancestor is buried here, you should have no issues ordering a marker. Enlist the nearby SAR Chapter. They should be eager to coordinate a marking ceremoney. Also coordinate with the cemetery for placement. I’m a geneaologist for my chapter in FL. The Beckley WV chapter did all the work for my ancestors ceremoney. I see that your ancestor is already listed in the SAR

This is an really interesting article. I can see how errors can be made. I do a lot of genealogy and have documented several thousand Revolutionary War soldiers. Probably the most common error is mixing up cousins, kinsmen and sometimes unrelated soldiers of the same name, this happens often especially on old DAR/SAR applications and records. One lady as an example joined the DAR through the service of my 5th Great Grandfather Wm. Ogle, a Cumberland Co., Pa. militiaman although he she was actually a descendant of his 1st cousin of the same name, an Ensign in Frederick Co., Maryland Militia.

There are indeed a lot of errors to be found, accidental or intentional. However, Patriot Arthur Johnson’s participation in the Siege of Norfolk was not disputed when it was stated in support of his pension application. See transcription at https://revwarapps.org/w10152.pdf. (As local SAR registrar, I just worked up a supplemental application on this man for one of our members.)