Fabulous: adj. 1) wonderful; 2) existing only in fable.

Emily Geiger is celebrated in numerous books and articles, memorialized on monuments, and portrayed in videos.[1] Her fame rests on the story that as a teenager she volunteered to carry a message from Gen. Nathanael Greene to Gen. Thomas Sumter in South Carolina when no man would dare to do so. As the story goes, Miss Geiger was stopped by enemy scouts who put her in a room and sent for an older woman to search her, and while waiting, she ate the message, the contents of which Greene had told her. Her mission undetected, she completed her journey and recited the contents of the message to Sumter.

Over time the tale acquired layers of conflicting ornamentation, mainly from writers who valued style over accuracy, but also from some serious historians. Benson J. Lossing, respected author and illustrator of Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, gave the above account of Emily Geiger’s ride in that work published in 1859.[2] In 1881, however, he gave a different version that he claimed was told to him in 1849 by a Mrs. Buxton. In that version not one, but two women searched Emily Geiger—Mrs. Buxton as a young girl, and her mother.[3] Lyman C. Draper, author of Kings Mountain and Its Heroes, was informed by sixty-six-year-old “Maj. Theodore Starke” of Columbia, South Carolina, that Emily Geiger did not ride alone, but was accompanied by his aunt, Rebecca Starke, then about seventeen years old. “The girls [were] put in a room, & women sent for to search them. The girls at once opened & read the letter, so as to know its contents, tore in two, each agreeing to eat one half of it. Emily soon made way with her portion; the other failed—when Emily, the good hearted, & frank Dutch girl, exclaimed, ‘Blast your dainty stomach, Rebecca Starke; give it to me, & I’ll eat it,’ & did so.”[4]

The story of Emily Geiger would be much different if the accounts attributed to Buxton or Starke had been better known, but it happened that a version by Elizabeth F. Ellet published in 1848 in The Women of the American Revolution became the most popular.[5] As others have noted, Ellet enclosed her account of Emily Geiger’s exploit in quotation marks and stated that it had previously “appeared in several of the journals.” After much searching we found that Ellet quoted a version by Judge William Dobein James printed first in the Charleston Mercury on July 21, 1824, and subsequently reprinted in other newspapers.[6] Unfortunately Judge James did not name his sources. As a youth James had served with Francis Marion, but he did not mention Geiger’s ride in his Sketch of the Life of Brig. Gen. Francis Marion published in 1821. By 1824 he had written a biography of Sumter that was never published,[7] and he may have heard about Geiger while researching that book

Judge James began his account as follows:

At the time General Greene retreated before Lord Rawdon from Ninety-Six, when he had passed Broad River he was very desirous to send an order to Gen. Sumter who was on the Wateree, to join him, that they might attack Rawdon, who had now divided his force.

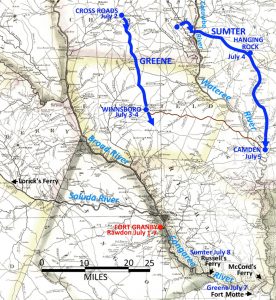

This passage by James is accurate, except that Greene’s original plan was to attack Fort Granby near Friday’s Ferry on Congaree River before Lt. Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon arrived there. On June 19, 1781, the approach of Rawdon had forced Greene to lift his siege of Ninety Six. Greene retreated northeast with Rawdon in pursuit until June 24, when Rawdon turned back to Ninety Six. Greene continued across Broad River, and on June 25 he decided to attack the British post at Fort Granby. He sent letters to Sumter and Marion urging them to join him near Friday’s Ferry for the planned attack.[8] Apparently anticipating Greene’s plan, Rawdon marched from Ninety Six to Fort Granby, arriving in the evening of July 1. In the following two days Greene marched toward his objective, stopping at Winnsboro on July 3 and 4, as shown on the accompanying map. At the same time, Sumter marched eastward across Catawba River, then southward toward Camden on Wateree River to check on the manufacturing of arms for his troops, arriving there on July 5. Thus according to James’s account, it would have been on July 4 or 5 that Greene needed to send a message to Sumter on Wateree River.

James continued his account by stating that Greene “could find no man in that part of the State who was bold enough to undertake so dangerous a mission.” Here the story of Emily Geiger’s ride begins to fall apart. Greene had already ordered Sumter to join him in the letter dated June 25, ten days before Sumter arrived on the Wateree River. Greene and Sumter exchanged several other letters on the subject before, during, and after Emily Geiger supposedly made her perilous ride, and all the letters appear to have reached their recipients within a day of being sent. On July 2 Sumter wrote to Greene that he intended to join him. On July 3 Greene wrote two letters to Sumter, one stating that Sumter’s “letter of yesterday overtook me on the march for the Congaree,” and the other stating that he had been informed that Rawdon arrived at Friday’s Ferry at about 11 PM on July 1. Both letters reached Sumter by the following day, as Sumter acknowledged in a letter to Greene written “near the Hanging Rock” on July 4. On July 6 Sumter wrote to Greene that he had arrived at Camden on the previous day, and that he would proceed a short distance and await further orders. There is no mention in this letter of anyone having conveyed a message orally to him from Greene. On July 7 Greene wrote to Sumter informing him that Rawdon was leaving Fort Granby, and on the next day Sumter acknowledged receipt of that letter.[9] Sumter was then at Russell’s Ferry on Congaree River, and on the following day he, as well as Marion, finally joined Greene. In the meantime Rawdon had gone to Orangeburg about thirty miles south of Fort Granby, where he remained until at least July 16.

It is apparent that the premise of Emily Geiger’s ride is baseless. We are not the first to observe that Greene did not need Emily Geiger to send a message to Sumter. Almost a century ago Alexander Samuel Salley, Jr. (1871-1961), secretary of the South Carolina Historical Commission, commented on it in a scathing article that opened with, “Some of the absurdities that are offered in support of spurious history would be amusing if so many people did not take them seriously.”[10]

Judge James’s account continues as follows:

The country to be passed through for many miles was full of blood-thirsty tories, who on every occasion that offered imbrued their hands in the blood of the whigs. At length Emily Geiger presented herself to General Greene, and proposed to act as his messenger; and the General, both surprised and delighted, closed with her proposal. He accordingly wrote a letter and delivered it, and at the same time communicated the contents of it verbally, to be told to Sumter in case of accidents. Emily was young, but as to her person or adventures on the way, we have no further information except that she was mounted on horseback upon a side-saddle, and on the second day of her journey she was intercepted by Lord Rawdon’s scouts.

This passage should have raised questions. Did Greene know Emily Geiger well enough to trust that she was not a Tory spy who would warn the defenders of Fort Granby of the planned attack? If Greene knew she was a true Patriot, would he really have been so callous as to expose her to “blood-thirsty tories, who on every occasion that offered imbrued their hands in the blood of the whigs?” The last clause in the passage quoted above tells us that Geiger’s journey occurred over a period of at least two days and brought her within reach of Rawdon’s scouts. The shortest route between Greene and Sumter (highlighted on the map) would have taken her no closer than twenty miles from Rawdon’s base at Fort Granby. It is unlikely that Rawdon would have had scouts that far distant, pinned between the two armies of Greene and Sumter.

Dr. W. T. Brooker, after “patient and untiring research extending over a period of several months” but without citing evidence, proposed a route that would have brought Geiger within range of Rawdon’s scouts.[11] He asserted that Emily first crossed Saluda River at Lorick’s Ferry about thirty-five miles southwest of Winnsboro, then went eastward toward Fort Granby another thirty-five miles distant. Along the way, according to Brooker, she was “accosted by three British troopers and learned for the first time that Rawdon had passed down the river on the south side the night before.” Rawdon had in fact arrived on the evening of July 1, but as seen above, Greene knew that already and should have warned Geiger to stay away.

James’s account continues:

Coming from the direction of Greene’s army, and not being able to tell an untruth without blushing, Emily was suspected and confined to a room; and as the officer in command had the modesty not to search her at the time, he sent for an old tory matron as more fitting for that purpose. Emily not wanting in expedient, and as soon as the door was closed and the bustle a little subsided, she ate up the letter piece by piece. After a while the matron arrived, and upon searching carefully nothing was to be found of a suspicious nature about the prisoner, and she would disclose nothing. Suspicion being thus allayed, the officer commanding the scouts suffered Emily to depart for where she said she was bound.

According to Brooker, the Tory woman who conducted the search was named Hogabook, and she was assisted by her daughter (Lossing’s Mrs. Buxton?). According to James, after being searched, Geiger

took a route somewhat circuitous to avoid further detention, and soon after struck into the road to Sumter’s camp, where she arrived in safety. Emily told her adventure and delivered Greene’s verbal message to Sumter.

According to Brooker, Geiger’s route was indeed somewhat circuitous: she proceeded thirty miles southeast to cross Congaree River at McCord’s Ferry the following morning, then rode another thirty miles northward to cross Wateree River, and at last recited the message to Sumter at Camden on the afternoon of July 4. A total of 130 miles in three days, in the July heat of South Carolina! We single out Brooker’s story simply to illustrate the lengths to which defenders of the story have gone in attempting to reconcile its incongruities.

According to James, in consequence of Emily Geiger’s ride, Sumter “soon after joined the main army at Orangeburg.” In fact, of course, the message would have been about Fort Granby, since Greene did not know that Rawdon had left for Orangeburg until July 7.[12] James concluded his account as follows:

Emily Geiger afterwards married Mr. Threrwits [sic: Threewits], a rich planter on the Congaree. She has been dead thirty five years; but it is trusted her name will descend to posterity among those of the patriotic females of the Revolution.

Often cited as proof of Emily Geiger’s existence is an invitation to her wedding to John Threewits on October 18, 1789. The original invitation is said to have been kept in a box with other relics, including “the set of jewels presented by General Greene to Emily on her wedding morning.”[13] Greene must have regarded her highly to have gone to such expense and trouble after being dead three years. If, as Judge James stated, Emily Geiger had been dead thirty-five years at the time he wrote about her, then she would also have been dead at the time of her wedding. Another encumbrance to the marriage would have been that John Threewits already had a wife.[14]

In addition to John Threewits, his brother Lewelling and another man have been proposed as Emily Geiger’s husband. “I will have to indict Emily for bigamy yet,” Salley sarcastically joked.[15] Lewelling Threewits did, in fact, marry a Geiger, but her name was Ann Mary (Anna Maria).[16] It is possible that Judge James got the name wrong, or Emily may have been a nickname for Ann Mary Geiger, but we have found no evidence for that. In any case, even if Ann Mary Geiger was Emily Geiger, it would not change the fact that the ride attributed to Emily Geiger was unnecessary and unsupported by any evidence.

Emily Geiger could simply have gestated in Judge William Dobein James’s mind at a time when it may have been in a precarious state. Two years after publishing his account of her, Judge James was accused of “habitual intoxication and drunkennness . . . daily, openly and publicly, and thereby hath often rendered himself from indisposition of body and imbecility of mind . . . unfit for understanding and correct decision of cases brought on for trial before him.[17] In 1827 he was impeached and removed from the bench.

Judge James did get one thing right: in spite of the lack of evidence, Emily Geiger’s name has descended to posterity among patriotic females of the Revolution. Emily Geiger’s fabulous ride might best be viewed as symbolic of the actual services performed by numerous unnamed women in the American cause.

[1]For examples see “Emily Geiger: a set of source documents,” sciway3.net/clark/revolutionarywar/geigeroutline.html.

[2]Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, vol. 2 (New York: Harper Brothers, 1859), 488-489.

[3]Benson J. Lossing, “Fair Messenger,” Harper’s Young People: An Illustrated Weekly II no. 86 (June 21, 1881), 530-531. Lossing stated that he “lodged at the house of a planter not far from Vance’s Ferry, on the Santee, where I passed the evening with an intelligent and venerable woman (Mrs. Buxton).” In the version in Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Lossing stated that he “passed the night at Mr. Avinger’s,” and he did not mention Mrs. Buxton. We have not found a Mrs. Buxton in census or other records. Also missing is a man surnamed Simons, who Mrs. Buxton said was a grandson of Emily Geiger living a few miles away.

[4]Notes by Lyman C. Draper on information from “Maj. Theodore Starke,” Draper Manuscript Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society, Thomas Sumter Papers, 11VV525, copy provided by the Southern Revolutionary War Institute, McCelvey Center, York SC. Transcribed at sciway3.net/clark/revolutionarywar/draper.html. “Maj. Theodore Starke” was more likely Mayor Theodore Stark (1805-1882), who was mayor of Columbia from 1866 until July 1868. localhistory.richlandlibrary.com/digital/collection/p16817coll10/id/13/. “Dutch” generally meant German, but the Geiger’s were German-speaking Swiss.

[5]Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Women of the American Revolution, vol. 2 (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1848), 295-297.

[6]We have been unable to find a copy of the original article from the Charleston Mercury. The version quoted here is from The Raleigh, North Carolina Register, August 10, 1824.

[7]Charleston Mercury, July 3, 1824, page 2. We do not know if the manuscript of James’s biography of Sumter survives.

[8]Nathanael Greene to Thomas Sumter and Greene to Francis Marion, June 25, 1781, in Dennis M. Conrad, ed. The Papers of Nathanael Greene vol. 8 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1995), 457-458.

[9]Papers of Nathanael Greene 8:482-486, 493, 503, 504, 511.

[10]A. S. Salley, Jr., “Grave of Emily Geiger: Myth Worshipers’ Mecca,” The State (Columbia, South Carolina), November 6, 1927.

[11]W.T. Brooker, “Emily Geiger’s Ride,” Orangeburg Times and Democrat, December 18, 1913, 6.

[12]Greene eventually decided not to attack because Rawdon was too well defended at Orangeburg.

[13]“Relics of Emily Geiger,” sciway3.net/clark/revolutionarywar/geiger21.html.

[14]A deed in Fairfield County, South Carolina Deed Book I, 165, dated June 25, 1782, indicates that John Threewits was married to Mary Thomas. Fairfield County SC Deed Records 1789-1797, image 418, www.familysearch.org. She was still the wife of John Threewits as late as February 27, 1802, as shown by a deed in Edgefield County SC Deed Book 22, 282-285. Edgefield County SC Deed Records 1802-1803, image 339, www.familysearch.org.

[15]“Insists ‘Emily Geiger’s grave’ is invention by myth builders,” The State, November 20, 1827, 10. Lyman C. Draper was told by Jacob and Abram Geiger of Lexington District that Emily Geiger married Lewelling Threewits. Sumter Papers 11VV529. “Lewelling” is the spelling given by his brother, John Threewits, and Lewelling Threewits signed his name as Lew’g Threewiits in the audited account for his Revolutionary War services. revwarapps.org/sc3039.pdf.

[16]Charleston County SC Deed Book Z-5, 352, September 27, 1787. Charleston, Charleston County SC Land Records 1787-1788, image 586, www.familysearch.org. Anna Mary Geiger apparently died soon after signing the deed, because Lewelling Threewits and his second wife, Eleanor Fitzpatrick, had a son, Llewellen Williamson Threewits, who reached legal age shortly before January 8, 1810 (thus born in 1788).

[17]“Proceedings of the General Assembly of South Carolina in the Matter of the Impeachment of Judge William Dobein James, November-December, 1827, and January, 1828,” page 6, dc.statelibrary.sc.gov/handle/10827/20769.

5 Comments

Excellent article. I did not know of Geiger before this. Certainly an important topic worthy of attention here.

I thoroughly enjoyed this well researched and witty article. I guess my SC Rev War knowledge has been seriously undeveloped as I’ve never heard of the fabulous saga of Emily Geiger. I wonder what the lady would think of serious scholars delving into her fabulous story 250 years after it didn’t happen. Thank you for taking the trouble to lay this story to rest with irrefutable evidence…although I suspect it will rise again.

An excellent article. My congratulations on some fine research and deduction.

South Carolina’s version of New York’s Sybil Luddington…

A well-researched article, that clearly demonstrates the difference between legend and documented facts. I truly love legends and believe they are important, but they are dangerous to rely on when writing actual history. Well done.