In 1812 when the British attacked the United States for the second time, Captain James Morris of the South Farms District of Litchfield, Connecticut, took quill to parchment to capture his six years of experiences during the Revolutionary War as an officer in Connecticut’s Light Infantry.[1] The light infantry was the battle-hardened, elite fighting force of Washington’s army and was at the front of the battle lines. Over the next several years when the spirit moved him he recounted for posterity his many battle experiences, including his heroism during the siege of Yorktown where he helped take redoubt 10 which broke the back of the British defenses and forced their surrender. He also described his survival as a prisoner-of-war for three-and-a-half years. This is Capt. James Morris’ story, one of unheralded heroism, patriotism, suffering, and triumph.

The Morris family immigrated from England in 1637 and was one the founding families of New Haven, Connecticut. Several generations prospered in New Haven before James’ father, known as Deacon James, married the recently-widowed Phoebe Barnes in about 1750 and decided to move north to the South Farms District of Litchfield where they started their family. Litchfield is an, “exceptionally handsome town, founded in 1715 in Connecticut’s northwest hills, and is considered one of the most historic locations in the state. During the Revolutionary War years, the village was a center of patriotic activity; and in a subsequent period of cultural flowering, the community earned a national name for its excellent educational institutions, fine houses, and sophisticated residents.” Morris’s farm was next to a carriage road that connected South Farms to the town of Bethlehem, located about seven miles south from the center of Litchfield and three miles north of the town of Bethlehem’s meeting house.[2]

James Morris was born on January 19, 1752 on a typical Connecticut farm for the times with a house which he described as “40 feet by 30, two stories high, kitchen back, a chimney at each end and a space way through, with a design that I should live in one half of the house.” The family attended church in Bethlehem and James was baptized by the famed pastor Doctor Joseph Bellamy in Bethlehem’s “old Meeting House.” Bellamy was one of New England’s leading pastors and social activists in his time.[3] The Morris and Bellamy families became close and remained close for many years. Jonathan Bellamy, Doctor Bellamy’s son, was good friends with both James Morris and Aaron Burr throughout his short life.[4]

James was a very bright child, leaning to read at age four. At age six, after he finished reading his father’s entire bible, his father honored his achievement by buying him his own bible which he cherished for many years. His youth was spent tending to farm duties, attending church meetings, and reading the bible with zeal. Throughout his life, even at a young age, Morris had an unwavering passion for education, learning, and teaching. In September 1771 at age nineteen he was accepted into Yale College and graduated in July 1775 with a degree in Divinity. He returned home and became a teacher in Litchfield’s Grammar School. But the war’s opening battle in Lexington, Massachusetts, in April 1775 disrupted his career plans. Unsolicited, the Connecticut State Legislature offered Morris the rank of ensign in the Connecticut Continental Line if he enlisted for six months. After consulting with his father and Doctor Bellamy he accepted the commission. His good friend and fellow Yale classmate, Jonathan Bellamy, received a similar offer and was commissioned at the same time.[5]

On August 27, 1776, under General Washington’s command, Ensign Morris’s first battle was the Battle of Long Island, after which he and the rest of Washington’s army safely escaped across the Hudson River. Three weeks later, on September 15 he was in the retreat from the city of New York when British troops landed on Manhattan. But his most memorable battle early in the war was the Battle of White Plains on October 28. And it was here his natural leadership skills became apparent. He wrote,

I was in the battle of White Plains, where sundry of the soldiers, my friends and acquaintances, were killed and where I heard the bitter groans of the wounded. The Captain and Lieutenant of the company were taken sick and were removed from the camp. The command of the company wholly devolved to me. The soldiers universally manifested a great respect for me, for my care of the sick and my attention to their wants, and for my sympathies in their distress.[6]

Near the end of his enlistment the Second Continental Congress offered Morris a promotion to second lieutenant if he reenlisted with the light infantry. With the army moving into winter quarters, and Litchfield being only seventy miles away, Morris returned home to consult with his father and friends before deciding. On January 1, 1777, Congress upped their offer; his rank would be first lieutenant if he reenlisted. He decided to not only reenlist, but he signed up for the duration of the war. His orders for the winter were to recruit soldiers from Litchfield and to oversee the inoculation of soldiers who hadn’t already survived smallpox. By the end of the May he had recruited “thirty to forty soldiers” and oversaw the inoculation of nearly 200 men. Tragically Morris’s fellow officer, classmate, and good friend, Jonathan Bellamy, died of smallpox on January 4 while stationed in New Jersey.[7]

At the beginning of June 1st Lieutenant Morris marched his new recruits to Peekskill, New York, where they joined Washington’s army.[8] It wasn’t long before the army went on the move. By the beginning of August, General Washington had moved his army to Pennsylvania in an effort to protect Philadelphia. British Gen. William Howe’s army had sailed out of New York and his ships were spotted in the Chesapeake Bay. In late August Howe’s army landed about fifty-five miles southwest of the city and on September 26 they captured Philadelphia.

A large portion of the General Howe’s army encamped outside of Philadelphia in the town of Germantown and General Washington planned a surprise attack on the British troops. At six o’clock on the evening of October 3 under the cover of darkness, Washington’s army began its twenty-mile march to Germantown. At first light on October 4 Washington’s troops fell upon the British. 1st Lieutenant Morris with the light infantry units were at the front of the attack. Despite a heavy fog Washington’s troops gained the advantage.[9] But Gen. Adam Stephen, who commanded the Connecticut Light Infantry, became lost in the heavy fog made worse with the addition of musket smoke. General Stephen blundered badly when he mistook a group of American troops for British troops and opened fire. The firefight caused both units to break and flee, and the British took advantage of it. This culminated in a near disaster for the Americans. Washington lost hundreds of men on the battlefield and another 500 of his men were captured. General Stephen was found to have been drunk during the battle. Shortly afterwards he was court martialed, stripped of his command, and booted out of the army.[10]

One of the captured men was 1st Lieutenant James Morris. He was now a prisoner-of-war and would remain one for the next three-and-a-half years. He wrote of his capture:

But the success of the day, by the misconduct of General Stephen, turned against. Many fell in battle and about five hundred of our men were made prisoners of War, who surrendered at discretion. I being in the first company, at the head of one column that began the attack upon the Enemy, was consequently in the rear of the retreat. Our men, then undisciplined, were scattered. I had marched with a few men nearly ten miles before I was captured, continually harassed by the British Dragoons and the Light Infantry. I finally surrendered, to save life, with the few men under my command, and marched back to Germantown under a guard.[11]

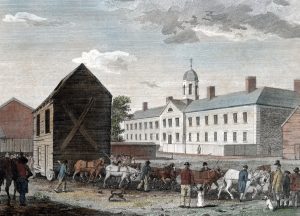

For the first six months he was held captive in Philadelphia’s New Jail, a most terrible place:

At this time and in this jail were confined seven hundred prisoners of War. A few small rooms were sequestered for the officers and each room must contain sixteen men. We fully covered the whole floor when we lay down to sleep, and the poor soldiers were shut into rooms of the same magnitude with double the number. The soldiers were soon seized with the jail fever, as it was called, and it swept off, in the course of three months, four hundred men who were buried in one continuous grave without coffin, lying three deep, one upon another . . . our number being daily decreased by the King of Terrors. Such a scene of mortality I never witnessed before. Death was so frequent that it ceased to terrify; it ceased to warn; it ceased to alarm survivors.[12]

By the end of April 1778 Morris had become so weak and ill he was granted a “parole of pardon” and was able to live outside the prison with the promise to remain within the city limits of Philadelphia. He lodged with a kind family who nursed him back to health. Once he regained some strength he frequented the Library Company of Philadelphia to read. He’d learned about the library from his jailers who brought him books from the library during his months in jail. At the end of May British forces withdrew from Pennsylvania and moved all the prisoners-of-war. Morris and the others were marched onto a ship which sailed to Long Island, New York.[13]

James Morris was granted another parole and lodged with a Dutch family in what is now Brooklyn. Compared to the horrors of the Philadelphia jail, his next three years as a prisoner-of-war were Elysian Fields. He spent his time gardening and walking, and became friends with his neighbor, Mr. Clarkson, who “owned the most extensive private library that I had ever known in the United States.” Clarkson allowed Morris free access to his collection and he immersed himself in books on ancient and modern history.[14]

On January 3, 1781, three-and-a-half years less one day after his capture, Morris was released in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in a prisoner exchange. He immediately marched north to New Windsor, New York, and rejoined General Washington’s army. He discovered that in his absence he had been promoted to the rank of captain. After a two month’s furlough to visit his family he rejoined the army and was given command of a light infantry company composed of men drawn from several Connecticut regiments.[15]

During the summer’s campaigns around Westchester County, New York, Morris commanded his company in several battles in which, “numbers fell on both sides. I was personally involved in several severe actions of which the Light Infantry must always be in front. I then experienced many narrow escapes, but still I was preserved, not a bone fractured, not even a flesh wound, while others fell by my side.”[16]

General Washington and French General Rochambeau received word on August 15, 1781, that the French navy was willing to support a military campaign against British general Charles Cornwallis’s forces stationed in Yorktown, Virginia. Washington and Rochambeau quickly devised a plan. They would feign an attack on General Howe’s army in New York to hold his army there while secretly marching both of their armies south to Yorktown. If this plan worked Cornwallis’s forces would be bottled up with no escape by land or sea. Washington could finally deliver a fatal blow to the British military, one he had worked for for more than six years.

On August 21, Captain Morris and General Washington’s army began their long breakneck march to the head of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia. On the August 29, they arrived and were transported by sail to Williamsburg where the American and French armies encamped. A few days later they marched the thirteen miles to Yorktown. On October 9 the historic siege of Yorktown began.[17]

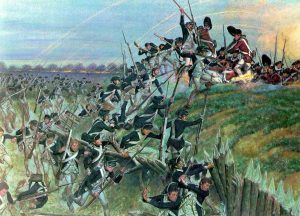

The relentless bombardment of Yorktown took its toll on the British forces, who were unable to escape through the Chesapeake Bay due to the French navy. General Washington’s army gained the advantage as, one-by-one, General Cornwallis’s land escape routes were sealed shut and the besiegers drew closer. Two redoubts—small, enclosed earthen forts—were critical to the security of the British position.These redoubts, numbered 9 and 10, held high ground and were protected by 200 battle hardened, well entrenched soldiers. Both redoubts were fortified with abatis, felled trees with sharpened branches facing outwards towards the enemy, and surrounded by deep trenches. A frontal assault was Washington’s only option to take the redoubts. Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton asked for and was given command of three battalions, a total of 400 men, to take redoubt 10. French General Baron de Viomeniland his 400 soldiers were to take redoubt 9.[18]

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton would personally lead the assault and asked for volunteers from his battalions to join him at the vanguard of the assault. The group called itself the forlorn hope as casualties were expected to be high. Capt. James Morris’scompany would be the first company behind the forlorn hope.[19]

On the evening of October 14 Washington ordered all cannons to begin firing on the redoubts to weaken them for the assault. The British did not see the gathering troops in the darkness of a nearly moonless night.

The attack opened when several incandescent shells were fired into the air to illuminate the ground for the attack. Noiselessly the troops advanced with “cold steel,” fixed bayonets on unloaded muskets. Surprise was on their side but a stumble by a soldier over the pock-marked terrain and the accidental firing of a musket would lose their advantage. Closely behind the forlorn hope Captain Morris and his company dashed across the quarter-mile of open land. Once spotted by the British, heavy musket fire ensued that went over the heads of the forlorn hope but landed on Morris’s troops. But the men raced forward. Quickly a small section of the abatis was hacked open and Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton hopped onto the shoulders of another soldier and sprang onto the parapet. The forlorn hope poured through the opening. Overrun, the seventy British defenders quickly surrendered and the redoubt was taken. Stunningly the whole assault and capture took less than ten minutes.[20]

Morris wrote of the assault in his memoirs:

On the 16th day at evening [actually the 14th] . . . the Light Infantry were ordered to take a Fort by storm . . . Accordingly as soon as twilight of the evening was gone, we began our march for that purpose. I then had the command of the first Company at the head of the column that supported the Forlorn Hope. Not a man was killed in Forlorn Hope; they were so near the Fort before they were discovered that the Enemy overshot them and the whole firing fell upon the main body. There were eight men killed near the head of the column, all within less than thirty feet of the place where I stood, and about fifty men were wounded. Yet in this dangerous situation, I by kind Providence was preserved. The Forlorn Hope, commanded by Colonel Alexander Hamilton, were successful in taking the fort.[21]

General Washington wrote of the assaults: “The bravery exhibited by the attacking Troops was emulous and praiseworthy—few cases have exhibited stronger proofs of Intripidity coolness and firmness than were shown upon this occasion”[22]

With both redoubts taken the American and French artillery were moved up and the final bombardment of the British began. On October 17 a red-coated drummer appeared followed by an officer waving a white handkerchief requesting a parley.[23] The next day negotiations for the British surrender were hammered out.

Of General Cornwallis’s historic surrender and the subsequent American celebration, Morris wrote:

On the 18th, a day of respite, our soldiers were directed to wash up and appear clean on the next day. . . . On the 19th day our whole Army and the French Army assembled; our Army on the right and the French Army on the left, about six rods apart, and each line reached more than a mile on an extended plain. We were thus drawn up to receive the vanquished. The British Army marched between our two Armies, drums beating their own tunes, colors muffled, and after they passed in a review of our Army they piled their arms on the field of submission and returned back in the same manner into York Town. . . . On the 20th day . . . General Washington ordered the Army to assemble for Devine Service and give thanks to God for the success of our arms. . . . How far preferable was this to people professing to be Christians than the heathenish custom of a drunken pow-wow and exulting over the humble vanquished. Here General Washington’s character shone with true lustre in giving God the Glory.[24]

After processing the captured military equipment Washington’s army marched back north to the east bank of the Hudson River, arriving in November 1781. Although the war didn’t end for another two years, in November 1782 Capt. James Morris was released from the army and returned back to civilian life in Litchfield, ending his Revolutionary War service.[25]

Throughout the next decades Morris was a leader in the Litchfield community, but is best remembered for his dedication to the advancement of education. In 1790 he established the Morris Academy, one of the first schools in the country to admit girls and young women after their primary education ended. He believed that, “where there was a virtuous set of young ladies there was a descent class of young men.” Over the next ninety years students across the expanding United States and nine foreign countries attended the academy.[26]

When the British attacked America in the War of 1812, James Morris was ceremoniously appointed First Major of Connecticut’s 2nd Regiment in June 1813 but did not campaign with the army.[27]

James Morris passed away on April 20, 1820, and was buried in the Morris Burying Ground, locally known as the East Morris Cemetery.[28]

Many Revolutionary War heroes were celebrated for their service and sacrifice by having cities and towns named in their honor. George Washington has fifty-three municipalities in the United States named for him, Benjamin Franklin has fifty, and Alexander Hamilton has thirty-nine.[29] First Major James Morris from the South Farms section of Litchfield was thus honored posthumously in 1859 when South Farms separated itself from Litchfield. The new town was named Morris, Connecticut. And in 1934, the town’s public school was named James Morris School.[30]

In 1891 Columbia University bought the original Morris family homestead and several adjoining farms to create a unique beloved educational summer camp named Camp Columbia, used by the university’s engineering department for over a hundred years. At the beginning of the new millennium in 2000, Columbia sold the 600-acre campus to the state of Connecticut and it is now Camp Columbia State Park.[31]

Over his lifetime James Morris gathered countless stones from the field’s rocky soil and used them to build the farm’s traditional New England stone walls. In 1942 alumnae of Columbia’s School of Engineering collected all the stones from his walls and used them to build the camp’s iconic seventy-five-foot water tower a short distance from where the Morris home once stood.[32] The water tower is now all that remains of the camp and the Morris homestead, and is the centerpiece of the Camp Columbia State Park. A staircase leads to a covered belvedere where visitors are treated to an unparalleled view of the surrounding New England countryside. Although not built as a monument to James Morris, it does serve as a fitting monument to his Revolutionary War service and dedication to the advancement of education in America.

[1]Robert Clark Morris, Memoirs of James Morris of South Farms in Litchfield (Yale University Press, 1933), III-IV.

[2]Morris, Memoirs of James Morris of South Farms in Litchfield, V-VI, 6; www.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/litchfield-the-making-of-a-new-england-town/.

[4]Ibid., 15; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Bellamy; aminoapps.com/c/hamilton/page/item/jonathan-bellamy/8Jel_WdHXIQLlJeeDkBV1pN2Q0WZgwD4p.

[5]Morris, Memoirs, 4-5, 11-15; aminoapps.com/c/hamilton/page/item/jonathan-bellamy/8Jel_WdHXIQLlJeeDkBV1pN2Q0WZgwD4p.

[7]Morris, Memoirs, 16-17; aminoapps.com/c/hamilton/page/item/jonathan-bellamy/8Jel_WdHXIQLlJeeDkBV1pN2Q0WZgwD4p.

[10]en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Stephen.

[18]www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/fix-bayonets-revolutions-climactic-assault-yorktown.

[20]Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) 163-164.

[22]allthingsliberty.com/2020/04/what-they-saw-and-did-at-yorktowns-redoubts-9-and-10/

[26]Barbara Nolen Strong, The Morris Academy; Pioneer in Coeducation (Torrington, CT: Quick Print, 1976),22, 28-34, 92-123; Morris, Memoirs, 53.

[28]www.findagrave.com/memorial/66757808/james-morris.

[29]en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_memorials_to_George_Washington#Municipalities_and_inhabited_areas; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_places_named_for_Benjamin_Franklin#Municipalities; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamilton.

[30]Strong, The Morris Academy,75-76; www.ctinsider.com/connecticut/article/Morris-Celebrating-Its-150th-Anniversary-16872808.php’

[31]portal.ct.gov/DEEP/State-Parks/Parks/Camp-Columbia-State-Park-Forest/Overview.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...