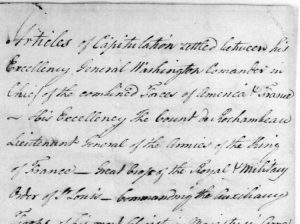

The surrender of the British Army at Yorktown in 1781 was implemented by the three-party Articles of Capitulation (“the Articles”), one of the most important documents of the Revolutionary War, since the surrender eventually led to the Peace of Paris (1783) and American independence. Curiosity as to the current location of the original Articles, i.e., those inscribed and signed October 19, 1781, led the writer to search for them, further intrigued by early twentieth century assertions that the American copy could not be found.[1] Since both Gen. George Washington and Lt. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis sent their governments copies of the Articles and retained the originals, the latter should be found in the papers of the two commanders.[2] Current repositories of those papers provide descriptions that imply or state they hold the original Articles,[3] which warrants a comparison between the originals and their published versions.

Chronology

The events of autumn 1781, leading up to the Articles set a groundwork of correspondence between the two generals. Cornwallis indicated his desire to negotiate the surrender of the British Army under his command in a letter to Washington on the morning of October 17, 1781. After further letters between them had established the required conditions of the surrender, two commissioners from each side met about 2 p.m. on October 18 at the Augustine Moore house near Yorktown to negotiate the specific terms to be codified in the Articles.[4] These negotiations lasted until 10-11 p.m., so that Allied commissioners Col. Henry Laurens and Louis-Marie, Vicomte de Noailles reached Washington’s quarters shortly before midnight with only a rough draft of the Articles.[5]

Since Washington’s diary for October 19 noted, “in the morning early I had [the Articles] copied,” the first fair copy of the Articles must have been inscribed during the initial hours of October 19, after the general had provided the commissioners with his position on each of the articles. Washington’s military secretary, Col. Jonathan Trumbull, Jr., penned this document, undoubtedly under the guidance of Laurens and de Noailles. When the Commander-in-Chief arose later that morning, perhaps 5-6 a.m., he reviewed Trumbull’s document then had another of his aides, Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, copy it.[6] At the same time, an aide to Lt. Gen. Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau made a French translation of the Articles. Tilghman required about two hours to prepare and proofread his copy; that work would have been completed by about 8 a.m.[7]

Washington then “sent word to Lord Cornwallis that I expected to have them signed at 11 O’clock . . . which [was] accordingly done.”[8] Allowing time for delivery and return, Cornwallis and his aides would have had about two hours to study the final version of the instrument of their surrender. His Lordship and his senior naval officer, Capt. Thomas Symonds, then signed the Articles and returned both copies to Washington, who was waiting in Redoubt No. 10. The general, Rochambeau, and Adm. Jacques-Melchior Saint-Laurent, Comte de Barras (in place of Adm. Francois Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse-Tilly, who was ill) signed the Tilghman copy of the Articles and Washington returned it to Cornwallis; Washington retained the Trumbull copy signed only by Cornwallis and Symonds.[9]

The Original Articles

The Articles consist of a preamble identifying the parties to the agreement, followed by fourteen articles covering the following terms:

- Statement of surrender

- Disarmament

- Method and time of surrender

- Protection of soldiers’ private property

- Soldiers to be prisoners of war

- Officers allowed parole

- Non-paroled officers allowed servants

- The ship Bonettato carry dispatches and soldiers to New York

- Traders’ rights and status

- Protection for Americans in the British Army

- Provision for hospitals for prisoners

- Provision for wagons for officers and surgeons

- Surrendered ships to belong to the French Navy

- No reprisals, and interpretation of wording

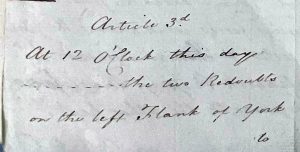

Beside each article the scribe inserted an indication of whether Washington had granted, rejected, or modified it. Following Article 14 is a date and place statement (“signature header”) and signatures of the parties, as described below.

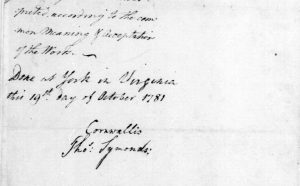

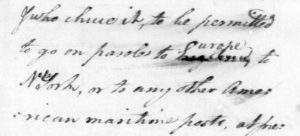

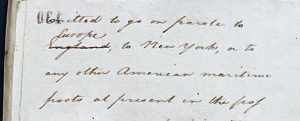

The Trumbull copy of the Articles is in the George Washington Papers in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, as is a contemporary copy.[10] This nine-page document is written neatly and shows little sign of the pressure Trumbull was under during those early morning hours. However, he was obviously thinking of a surrender of British personnel only when he wrote in Article 6 that officers would “be permitted to go on parole to England, to N York, or to any other American maritime ports, at present in the possession of the British Forces.” His use of “England” proves useful to these observations. Recognizing that the Articles in general and Articles 3, 6, 8, and 9 specifically required that the document have an effective date, Trumbull added this signature header at its end: “Done at York in Virginia this 19th day of October 1781.” The British signed directly below this.[11]

The Tilghman copy of the Articles is contained in the Cornwallis Papers in the British National Archives.[12] A ten-page document in the secretary’s graceful handwriting, it differs from the Trumbull copy in that most of the latter’s uses of “&” were converted to “and.”[13] It also incorporates the following subtle differences that identify which original was the source of many of the later copies:

| Article | Trumbull copy | Tilghman copy |

| 5 | A field officer from each nation, viz. British . . . | A field officer from each nation, to wit British . . . |

| 9 | The Traders to be considered as prisoners of war on parole. | The Traders to be considered as prisoners of war upon parole. |

| 13 | The shipping & boats in the two harbours . . . | The shipping and boats in the two harbors … |

Tilghman omitted a signature header and instead inserted in Article 3, following “at 12 o’clock this day,” a blank in which the date was to have been inserted by a signer. Cornwallis did not insert the date when he signed the document, leaving that for Washington to add.

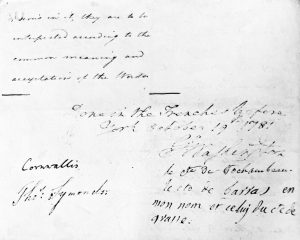

In lieu of that, Washington added this header adjacent to the British signatures: “Done in the trenches before York October 19th 1781;” his signature and those of his French colleagues follow.

Only Two Signatures?

In a 1938 paper on missing archival material, Randolph G. Adams of the Clements Library wrote: “When, in editing the writings of Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick came to look for the original manuscript of the articles of capitulation at Yorktown signed by Washington, Cornwallis, Symonds, Rochambeau and Barras, he could not find it in the possession of the United States government . . . A signed copy should have gone to the Americans, but where was it?”[14] Others reached a similar conclusion, based on the assumption that all the parties to the Articles signed all (in this case two) copies and distributed them to all signatories.[15] Certainly, Cornwallis required a copy signed by the allies to commit them to articles that would impact his surrendered troops for months if not years; Washington recognized that and sent him the Tilghman copy that included all five signatures. However, Washington’s goal was the surrender, disarmament, and dispersal of Cornwallis’ troops, events that took place later in the day October 19 or on subsequent days, and to assure that he needed only the signature of Cornwallis on the Articles.[16] The addition of his own signature and those of his French colleagues to his copy was, to him, superfluous. This is confirmed by American copies of the Articles made a few days after the surrender and printed in Philadelphia newspapers, contained in the Continental Congress Papers, and prepared for private use; these show that Cornwallis and Symonds alone signed the Articles that were sent to Congress.[17] Hence, the Trumbull copy in the Library of Congress bearing only the signatures of the two British commanders is the copy Fitzpatrick sought.

The French Translation

Rochambeau and de Barras joined Washington in signing the Tilghman copy of the Articles which of course was in English. Rochambeau had one of his aides prepare a translation to send to his government that concluded with the statement, Traduit litteralement d’apres l’original reste entre les mains du general Washington (literally translated from the original, still in the hands of General Washington).[18] That faithfulness to the Trumbull copy includes Angleterre as a destination in Article 6, the significance of which was underscored by subsequent developments. This document was included with the French general’s letter of October 20 to his Minister of War, Philippe Henri, Marquis de Segur, informing him of the surrender. Copies of that letter were carried to France by two of Rochambeau’s officers via frigates that left several days apart; while both arrived safely, the original of the French translation of the Articles has not been found.[19]

Additional Observations

Washington’s diary mentions having had the Articles copied after he reviewed Trumbull’s work the morning of October 19. The above chronology demonstrates that there was time for Tilghman to make only one copy before it and the Trumbull copy were taken to Cornwallis to be signed. Thus, only two copies of the Articles were made that morning, one in each aide’s handwriting.

To the layman’s eye the signatures of Cornwallis and Symonds on the Trumbull copy match those on the Tilghman copy and that of Cornwallis matches others known to be his. All other extant “signed” copies of the Articles either state they are copies or contain signatures obviously in the same handwriting as the text.[20]

Cornwallis noted that the wording of Article 6 meant that surrendered officers were allowed to go to England but not to Europe, imposing a hardship on the twenty percent of his officers who were from the German states. His Lordship assumed (correctly since Washington did not object) that this was an unintended drafting error and had “England” crossed-out and “Europe” inserted above it in both copies he signed.[21] Supporting this scenario is the distinctive handwriting of “Europe,” which appears to be the same in both copies and differs from that of Trumbull and Tilghman. Also, the French translation includes Angleterre in Article 6 with no cross-out, indicating the latter was not an American correction.[22]

The Trumbull and Tilghman copies of the Articles alone contain this alteration; all other copies, including those made within days of the surrender, contain only the word “Europe” in Article 6.

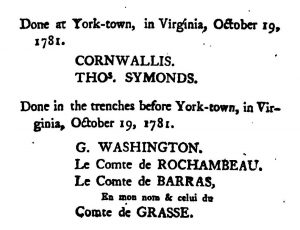

The Two Signature Headers

Various publications have printed the Articles with all five signatures and both signature headers, i.e., “Done at York in Virginia this 19th day of October 1781” and “Done in the trenches before York October 19th 1781.” In many of these “Yorktown” is used instead of “York.” However, neither of the originals of the Articles includes both headers nor uses “Yorktown” in its single header, raising the question as to the origin of that practice. The first use of both signature headers is in a pamphlet published by Cornwallis in 1783, in response to General Sir Henry Clinton’s pamphlet attempting to place the blame for the Yorktown campaign on his former subordinate. Cornwallis’ pamphlet contains a copy of the Articles that incorporates both signature headers with “York” changed to “York-town,” and with the word “pretext” in Article 14 changed to “pretence.”[23] These features appear in the version of the Articles printed in the works of Banastre Tarleton, Jared Sparks, Henry P. Johnston, and others spanning 163 years.[24]

Why did Cornwallis make this change to the Articles in his pamphlet since, in December 1781, the London Gazette had printed the Tilghman copy (originally transmitted by Cornwallis) showing only the “Done in the trenches . . .” header?[25] Possibly because this pamphlet was a defense against Clinton’s criticism of his actions during the campaign and particularly at Yorktown. The header in the London Gazette version implied that Cornwallis had gone to the trenches to surrender to the allies. Adding “Done at York-town. . .” served as a reminder to all readers of his personal location during the siege and surrender.

Summary

Washington and Cornwallis retained the two originals of the Articles, sending copies with their reports on the surrender to their governments. No doubt that was to protect and preserve the originals given the vagaries of transportation at the time, compounded by the hazards of war. Consequently, those documents have survived to the present in the papers each man left and are preserved in government repositories in their respective countries. They were the only two copies of the Articles made the morning of October 19, 1781, and their originality is confirmed by internal evidence. Many versions printed subsequently differ slightly from the text of these originals.

[1]Randolph G. Adams, “The Character and Extent of Fugitive Archival Material,” The American Archivist 2, no. 2 (April 1939), 85.

[2]George Washington to Thomas McKean, October 19, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07206; Charles Cornwallis to Henry Clinton, October 20, 1781, PRO 30/11/74, folios 113-116, UK National Archives. However, the history of Washington’s papers following his death indicates there were many opportunities for documents such as the Articles to have gone astray. See: George Washington Papers: A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress (Washington: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, 2009), 5-13. Clinton had a copy of the Articles made for his files prior to sending them to his government; it is in the Clinton Papers, Volume 18212, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[3]The Library of Congress online description refers to the Articles as “Capitulation Articles, with Copy,” while the UK National Archives online description states that their copy is “the original,” possibly Cornwallis’ personal copy. See, respectively: www.loc.gov/item/mgw429634/and www.discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C6672221.

[4]Edward M. Riley, “St. George Tucker’s Journal of the Siege of Yorktown, 1781,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 5, no. 3 (July 1948): 392; “Henry Knox to John Adams, October 21, 1781,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-12-02-0020.

[5]David Cobb, “Before York Town, Virginia,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 19 (1881-1882), 69; “General Richard Butler’s Journal of the Siege of Yorktown, The Historical Magazine8, no. 3 (March 1864), 110; Diary of George Washington, entry for October 18, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-03-02-0007-0006-0012.

[6]Diary of George Washington, entry for October 19, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-03-02-0007-0006-0013. In the first copy the disposition of each article, which could only have come from Washington, is in the same handwriting as the rest of the text, i.e., that of Trumbull. Therefore, Washington’s instructions must have been provided soon after the commissioners returned. The speculated time of Washington’s rising is based on his reputation for being an early riser.

[7]The writer required an hour and a half to make a neat handwritten copy of Trumbull’s copy using a ballpoint pen. Tilghman would have required more time to make his handsome copy using a quill pen and undoubtedly checked the completed document carefully against the Trumbull copy. Since he began after Washington had reviewed Trumbull’s copy, say around 6 a.m., he likely would have completed his work around 8 a.m. Tucker’s journal says the Articles “were signed and exchanged” at 9 a.m.; assuming this means they were completed and sent to Cornwallis for signing at 9 a.m. suggests the development sequence began slightly later. See, Riley: “St. George Tucker’s Journal,” 392.

[8]Diary of George Washington, entry for October 19, 1781.

[9]Edward M. Riley, “Yorktown During the Revolution,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 57, no. 3 (July 1949), 283. The Articles had to be conveyed from Washington’s Headquarters to Cornwallis’ Headquarters, about three miles, and from there to Redoubt No. 10, less than one mile.

[10]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Capitulation Articles, October 19, 1781, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The “contemporary copy” may have been the one included by Washington with his report to the Continental Congress.

[11]Trumbull’s journal covering the siege and surrender has survived but does not mention his role as a scribe of the Articles. See “Minutes of Occurrences respecting the Seige and Capture of York in Virginia, extracted from the Journal of Colonel Jonathan Trumbull, Secretary to the General, 1781,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society14 (1875-1876), 337.

[12]“Articles of Capitulation,” PRO 30/11/74, folios 128-134, UK National Archives. The writer is indebted to Dr. Benjamin L. Huggins of the Washington Papers for pointing out that the last four lines on the first page are in Trumbull’s hand. The balance of the document appears to be in Tilghman’s hand.

[13]Tilghman converted thirty-seven of Trumbull’s thirty-eight “and signs” (modified “+” signs shown in the text as “&”) to “and.” Other differences between the two copies are varied use of capitalization and punctuation.

[14]Adams, “The Character and Extent of Fugitive Archival Material,” 85.

[15]“The Background and Purposes of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library,” (New York, 1939), 2; Correspondence of General Washington and Comte de Grasse, The Institut Francais de Washington, ed. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1931), xiii.

[16]In Washington’s view Cornwallis was the commander of all British forces at Yorktown. However, Cornwallis did not have the authority to surrender Royal Navy or merchant ships, so he had Captain Symonds sign the Articles as well.

[17]Pennsylvania Evening Post (Philadelphia), October 25, 1781; Continental Congress Papers, Letters from George Washington 10: 299-307, www.fold3.com; “Articles of Capitulation,” GLC02437.0955, Henry Knox Papers, Gilder Lehrman Institute: New York.

[18]Henri Doniol, Histoire de la Participation de la France a l’Etablissement des Etats-Unis d’Amerique (Paris: Libraire des Archives Nationales at de la Societe de l’Ecole des Chartes, 1892), 5: 568-573.

[19]Doniol, Histoire de la Participation, 5: 567; The Campaign in Virginia 1781, Benjamin Franklin Stevens, ed. (London, 1888), 2: 204 provides a nineteenth century archival location of the French translation of the Articles; efforts to locate that document today were not successful.

[20]For example, see Copy of the Articles of Capitulation between General George Washington and Earl Cornwallis after the Battle of Yorktown, General Henry Sewall Papers, Maine State Archives, Augusta. One exception to the statement in the text is the copy made by Maj. Samuel Shaw, aide to Brig. Gen. Henry Knox, in which Shaw attempted to duplicate the British signatures. See “Articles of Capitulation,” GLC02437.0955, Gilder Lehrman Institute. Contemporary unsigned copies also exist. See “Articles of capitulation of the British forces under Lord Cornwallis, 1781,” Mss12: 1781 Oct 19:1, Virginia Museum of History & Culture, Richmond.

[21]A draft of a portion of the Articles, possibly by one of the British commissioners who negotiated them, includes part of Article 6 in which the relevant word is “Europe” indicating that the commissioners intended to use that word. See Draft of the articles of capitulation and surrender of the British forces under Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown: (Yorktown, October 1781), Accession Number MA 488.3, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

[22]Doniol, Histoire de la Participation, 5: 570. Had the French translation been made later than the morning of October 19, the relevant destination in Article 6 would have been l’Europe.

[23]Earl Cornwallis, An Answer to that part of the Narrative of Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Clinton, K.B. Which relates to the Conduct of Lieutenant-General Earl Cornwallis during the Campaign in North-America, in the Year 1781 (London: Printed for J. Debrett, 1783), 226.

[24]Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (Dublin, 1787), 452-456; The Writings of George Washington, Jared Sparks, ed. (Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1888), 8:533-536; Henry P. Johnston, The Yorktown Campaign and the Surrender of Cornwallis (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1881), 187-189; American Historical Documents 1000-1904, Charles W. Eliot, ed. (New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1910), 172-173; The Moore House/Yorktown Battlefield/Colonial National Historical Park (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950).

[25]London Gazette, December 15, 1781. The newspaper printed the Articles received by the British government from General Sir Henry Clinton.

8 Comments

What a great detective story! Nice work tracking down these important documents.

Ad fontes forever!

A really interesting deep dive and investigation! I’m a big fan of such explorations based on extant archive material. One correction, however – it was Lt. Col. John Laurens, not his father Henry Laurens, who negotiated the terms (considering Henry was in the Tower of London at the time!).

Anna,

You are certainly right about which Laurens was the negotiator. Thanks for that correction.

Bill

Salut –

de Grasse never set foot on American soil but there is no evidence that de Grasse was ill. More importantly, Mr. Reynolds writes of the two “Allied commissioners Col. Henry Laurens and Louis-Marie, Vicomte de Noailles.” There were three. The third was Guillaume Jacques Constant de Liberge de Granchain (1744-1805), Intendant of the Squadron of Jacques-Melchior Saint-Laurent, comte de Barras, who represented the French navy. In a long letter to his mother from “Camp before York 20 October 1781” he wrote (excerpt) “I don’t know whether it was circumstance that made M le comte de Grasse to pick me to go to headquarters during the siege to deal with the generals of the land [armies] about the maritime operations. This commission which at first threw me into great embarrassment turned strongly into my favor. It led me to be one of the negotiators charged with bringing about the articles of surrender, and I am at this point occupied with taking possession of the vessels and other naval effects of the enemies”. Almost 50 letters written from America are in Archives familiales of Capitaine de Vaisseau Guillaume-Jacques-Constant comte de Liberge de Granchain. Call number 764AP, 8.7. Archives nationales – Département des Archives privées, Paris, France. (My translation)

He is also mentioned in the GW Papers. Washington informed de Grasse on October 19, 1781: “Mr de Grandchain assisted yesterday in digesting the Articles of Capitulation; as soon as this business is terminated I propose to do myself the honour of waiting upon Yr Excelly on board. I have the honor etc.

https://founders.archives.gov/?q=grandchain&s=1111311111&sa=&r=4&sr=

Robert,

Concerning de Grasse’s illness, Washington mentions it in the October 19, 1781, letter to the admiral in which he stated that “Grandchain assisted yesterday in digesting the Articles of Capitulation ….” I had interpreted the quote to mean that Washington consulted with Grandchain (as well as Rochambeau) concerning the language of the Articles, rather than meaning that Grandchain was a commissioner. I suppose Grandchain’s letter to his mother from which you quoted could be understood either way. However, note that Washington’s diary entry of October 18, 1781, stated that “Colo. Laurens & the Viscount De Noailles … were appointed [commissioners] on our part.” Grandchain is not mentioned.

Bill

Bill –

the original reads:

Elle [the order to go on land] m’a conduit a être un du commissaires chargés de convenir des articles de la Capitulation, et actuellement je suis occupé a prendre possession du bâtiments et autres…

You can interpret that any which way you want to. And yes, Washington did not mention Granchain in his letter to Congress. Odd to think, wouldn’t you say, that Cornwallis would have Symonds sign for the Royal Navy but there would not be anybody there for the French Navy?

Sharing link on Facebook page, “Yorktown Campaign Route.”

Salut –

“two of Rochambeau’s officers via frigates that left several days apart”.

Rochambeau had selected the duc de Lauzun and William de Deux-Pont as “the two superior officers who have performed the two most distinguished feats.” Lauzun’s feat was the cavalry engagement with Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton on 3 October in Gloucester; Deux-Pont’s the storming of Redoubt No. 9 on the night of 14 October. On 22 October 1781, the duc de Lauzun sailed for France on the frigate Surveillante with the news of the victory at Yorktown and anchored in Brest in the evening of 19 November. William de Deux-Ponts sailed from Virginia on the frigate Amazone on 1 November, reached France even faster on 20 November after a 20-day crossing.