The Articles of Confederation described the first government of the new United States. As one may imagine from understanding the later debates on the Constitution in 1787, there were a number of points of contention on the Articles that were later re-argued for the Constitution. But there was one issue in the debate on the Articles that would ultimately play a significant role in the way the United States coalesced and grew. It did not have to be “re-litigated” when the Constitution was debated. The issue was the disposition of the continent’s western lands, those lands beyond the recognized borders of the British colonies. Who would own them, and how would they be managed? Despite all their failures, the settlement of the western lands question would become the most enduring contribution of the Articles of Confederation.

The founders had the foresight to begin design of a new government while the Declaration of Independence was still being drafted. On June 12, 1776, the Continental Congress formed a committee consisting of a single representative from each colony: Josiah Bartlett (New Hampshire), Samuel Adams (Massachusetts), Stephen Hopkins (Rhode Island), Roger Sherman (Connecticut), Robert R. Livingston (New York), John Dickinson (Pennsylvania), Thomas McKean (Delaware), Thomas Stone (Maryland), Thomas Nelson, Jr. (Virginia), Joseph Hewes (North Carolina), Edward Rutledge (South Carolina), Button Gwinnett (Georgia), and Francis Hopkinson (New Jersey). It delivered an initial draft just one month later, penned by John Dickinson. The Articles were debated by the full Congress until November 15, 1777, and that month the President of Congress sent a circular letter with the Articles to the state legislatures for their review and approval.

Yet the Articles were not fully ratified until February 2, 1781! Why so long? Besides the fact that there was a war going on that naturally occupied people’s time, the western lands issue held up the Articles for nearly four years after the draft was issued. To place this timing in some context, the Articles were finally approved only about seven months before the British surrender at Yorktown and two years and six months before the formal ending of hostilities in September 1783. The new nation got through most of the war without a fully approved structure of government. In the interim, the Continental Congress ran things, and while it probably hewed closely to the principles outlined in the Articles, the Articles were not the official law of the land.

When Dickinson delivered his draft, many debates arose, both before the document left Congress and after it went to the states for review. Two major issues involved apportionment of costs and representation in Congress. These two foreshadowed similar debates on the Constitution.

The argument on the apportionment of costs hinged on a familiar issue that would arise again—slavery, and whether enslaved people should be counted if the allocation was based on population. Benjamin Harrison of Virginia offered a compromise that two slaves count as one free laborer, presaging the three-fifths compromise later incorporated into the Constitution. Although a vote along sectional lines would have favored the counting of enslaved people in some manner, Congress eventually abandoned headcounts altogether and decided to allocate costs based on relative land values (a seemingly difficult and subjective number to quantify).[1] A parallel discussion emerged on voting rights by state and whether they should be weighted in some way or simply be one state, one vote. This time the fault line was between the large states and the small states. Roger Sherman of Connecticut proposed that two votes be taken on each question, one with voting weighted by state population and the other being one vote per state. Apparently, the delegates were not yet ready for the Connecticut Compromise of 1787 and voted to go with one vote per state.

This brings us to our main event—the debates over western land holdings. This is where things bogged down, at least for one state. The new lands acquired in the 1783 Treaty of Paris represented a vast territory stretching from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River between the southern shores of the Great Lakes and Spanish Florida. To whom did these lands belong? Initially seven states claimed them based on old colonial grants and Indian treaties: Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. These states supported this stance by claiming that the state of war with Britain meant that their borders reverted to those specified by their original colonial charters, which were expansive although still limited by the proclamation line of 1763 which limited expansion to the Appalachians. Many of these state claims were overlapping. The other six states had no claims beyond their existing boundaries.[2] Termed “landless” states, they feared that the other states, enlarged by western territories, would become economically and politically dominant[3]

In the initial comment period for the Articles, Maryland, one of the landless six, proposed the following change to Article IX: “the United States and Congress assembled shall have the power to appoint commissioners, who shall be fully authorized and empowered to ascertain and restrict the boundaries of such confederated states which claim to extend to the River Mississippi or the South Sea.”[4] This amendment was deferred and then voted down. So started Maryland’s battle.

“Maryland’s refusal to agree to the Articles of Confederation until Congress should be given some portion of the West,” writes one historian, “was interpreted as a result of the ‘farsighted policy of Maryland in opposing the grasping land claims of Virginia and three of the Northern States.’”[5] This sentiment grew, frankly, less out of any noble patriotic aim or idealistic long-term vision than it did out of a straight-up jealousy of Virginia and the hopes and speculative dreams of the land companies within it.[6]

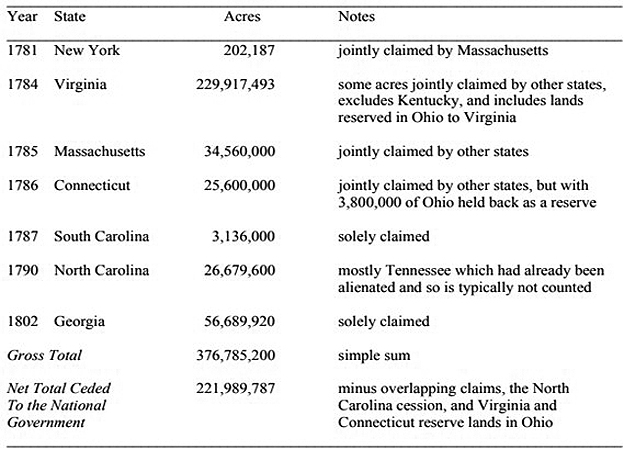

The landless states wanted the Articles to stipulate that Congress limit the boundaries of those states claiming western lands. Under their proposal, Congress would take ownership of the western lands and sell off them off, using the money to benefit all by paying off war debts. Beyond pure economic concerns, the landless states had concerns that Virginia, already the most influential state in the union, would raise its influence even more given its massive western holdings (230 million acres, over 60 percent of the total western acreage claimed by the seven states).[7] Figure 1 shows the land holdings of the colonies at the time the Articles were adopted.

Figure 1: Land holdings of colonies in 1781. (VirginiaPlaces.org)

Some states such as Virginia claimed that their borders extended all the way to the South Sea (the Pacific Ocean), which included land claimed both by the United States and Native Americans, and land claimed by Spain.

Dickinson’s first draft of the Articles provided for Congressional governance over the western lands, though weakly. The Articles implied that Congress had the authority to judge matters related to the boundaries of states or their jurisdiction, but only as a last resort. Adding to the uncertainty of this arrangement, Congress lacked the executive power to enforce such decisions. Even if Congress were to rule in matters of interstate conflict, it would be up to the states to abide by that ruling.

Samuel Chase of Maryland was a particularly strong supporter of vesting the power of controlling state borders in Congress. Benjamin Harrison of Virginia countered that Virginia’s large claims were simply based on its charter, just as Maryland’s were based on its. Harrison warned that “gentlemen shall not pare away the Colony of Virginia.”[8] Along the same lines, Benjamin Huntington of Connecticut, a state with western lands (albeit much smaller than Virginia’s) questioned whether the landless states could prove that Virginia’s claims and associated power posed a threat to the landless states and, even if they did, it didn’t follow that Congress could claim the right to alter the chartered borders of a colony. He urged unity against what he termed “mutilating charters.”[9]

At this stage, the power of Virginia won out. The delegates realized that, if stripped of its vast territories, Virginia would likely opt for disunion. They relented and Dickinson’s provision giving Congress power over the western lands was struck. But the battle was not over for the landless states, and they searched for other ways to solve the problem. But they had little defense other than to withhold approval of the Articles. In October they made a final attempt to write their desires into the Articles of Confederation. They offered a series of motions designed to give Congress power to fix the western limits of the landed states. Each of the motions failed.[10] Eleven states approved the Articles between late 1777 and late 1778. Virginia, perhaps not surprisingly, was the first to approve. Delaware held out for a year, approving in 1779. Maryland, now the lone non-approver, kept on sparring with Virginia.

Virginia’s General Assembly pushed back, after it signed but Maryland still hadn’t, against what it considered unlawful interference by the nascent national government in an independent state’s internal affairs. The legislature issued a “remonstrance” on December 14, 1779

Should congress assume a jurisdiction, and arrogate to themselves a right of adjudication, not only unwarranted by, but expressly contrary to the fundamental principles of the confederation; superseding or controuling the internal policy, civil regulations, and municipal laws of this or any other state, it would be a violation of public faith, introduce a most dangerous precedent which might hereafter be urged to deprive of territory or subvert the sovereignty and government of any one or more of the United States, and establish in congress a power which in process of time must degenerate into an intolerable despotism.[11]

But Maryland remained stubborn. By 1780 they were still flatly refusing to ratify until this issue was solved by the states claiming western lands ceding them to the national government for “the general benefit.” The problem of western land claims was clearly the only obstacle to final ratification of the Articles of Confederation.[12] Besides Maryland withholding its approval, the only other tactic for the landless states was to press states with such claims to cede their claims to the national government, despite a lack of any real negotiating leverage.

One concern that surfaced in the debate was that the states with western land holdings would move toward empire at some point. On the frontier westerners worried about the imperial or colonial intentions of the East, and they talked about it quite freely. It would be difficult to disabuse those states of the visions of their own colonial holdings.[13] With freebooters on the loose like Aaron Burr and James Wilkinson, the latter (and perhaps the former) under the pay of the Spanish, anything was possible. It is not overstating the case to say that the “conflicts over which governments had jurisdiction over these lands created the first crisis of disunion.”[14]

Examples of this had surfaced already. In 1784 the North Carolina Assembly entertained a proposal for three counties of its western lands to be organized as the state of Franklin. The state even went so far as to hold a constitutional convention, agreeing on things like a unicameral legislature and guarantees of religious freedom. John Sevier was appointed governor, and a delegate was dispatched to Congress to request that Franklin be admitted to the union as the fourteenth state, for which there were no real processes or rules. Due to a number of complications with land treaties with the Cherokees, the state of Franklin teetered; by 1787 new leaders rallied for a return to North Carolina sovereignty. Sevier tried but failed to interest the Spanish governor in New Orleans to annex the state, and was as a result arrested for treason. He was rescued from prison by a heavily-armed gang of followers before he could be tried. In February of 1789, Franklin leaders including a repentant Sevier took an oath of allegiance to North Carolina, clearing the way for North Carolina to include the Franklin land as part of their state in the session of Congress. The short existence of the state of Franklin, if nothing else, provides a representation of how Congress did not want the process for new states to work.[15]

When Maryland’s resistance finally broke, it wasn’t because Virginia wore them down. Instead, it was precipitated by a series of raids by the British navy and privateers throughout the Chesapeake Bay region in 1780. When Maryland asked the French to provide ships to block the raids, the French responded with a suggestion that Maryland should ratify the Articles of Confederation first.[16] The ongoing campaign by landless states also had slowly worn down opposition to those states’ proposals, and later in 1780 Congress resolved that all lands ceded by states to the national government should be “disposed of for the common benefit of the United States.” As these conditions were hammered out, states one by one from 1781 through 1802 ceded their western lands to the national government. The commitment to cede these lands in 1781, along with the practical considerations of French defense support, opened the door to the final ratification, by Maryland, of the Articles of Confederation on March 1, 1781.[17] On March 1, 1784 Congress accepted Virginia’s cession of western lands, three years after the completion of the Confederation.[18]

The avalanche of state cessions is shown in Figure 2.[19]

Figure 2: Cessions of land from each state, 1781—1802. Used with permission of Farley Grubb, National Bureau of Economic Research.

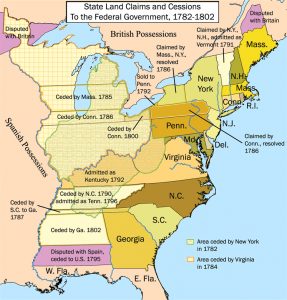

Between 1780 and 1787, Congress affirmed its authority over the ceded lands and established the basic principles and policies of land distribution and governance for decades to come. This was accomplished by the passage of three great ordinances—the Ordinance of 1784, the Ordinance of 1785, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787—the first initiated under Thomas Jefferson and then fleshed out and carried forward by others in Congress, with the 1785 and 1787 Ordinances superseding the 1784 Ordinance.[20] The cessions happening simultaneous to this are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Land cessions from 1782 thru 1802. (Wikipedia.com)

Particular attention should be paid to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which historian Robert Remini has dubbed the “Bulwark of the Republic.” The signature achievement of the Articles of Confederation government, this Ordinance was one of the most important, progressive, and far-reaching legislative acts in the nation’s history.[21] The Northwest Ordinance, along with the Land Ordinances of 1784 and 1785, set up the structure for the orderly addition of states to the union. Until these Ordinances, there had been significant dangers of states setting up their own colonial empires or territories coming under foreign influence.

Dr. James White, a North Carolina congressman who in the words of one recent historian had a dream of empire for “Greater Franklin,” told Don Diego de Gardoqui, the Spanish minister to the United States, that the western settlements would separate from the United States if Spain would reopen the Mississippi River, provide a military alliance and commercial concessions, and permit them to expand their territory down the Tennessee River past the Muscle Shoals to the headwaters of the Alabama and Yazoo Rivers.[22] Another such threat involved the ever-scheming James Wilkinson. He came to Kentucky from Maryland around 1783 and quickly established himself as a leader of the movement to separate Kentucky from Virginia. He demanded radical action, and there was plenty of talk about establishing an independent nation. Wilkinson and his friends called for a declaration of independence from Virginia and from the United States. It was decided to take the issue to the people and the question of separation was narrowly rejected, a little too close for comfort.[23]

What made the difference, what completely turned the situation around, was the passage of the Northwest Ordinance. It was passed by a skeleton crew of only eighteen congressmen as all the big guns were either at the Constitutional Convention or out of the country on diplomatic missions. But the backbenchers came through, passing the ordinance on July 13, 1787. Now the West knew that Congress had a policy with respect to the territories and that that policy meant colonial rule until such time as the settlers were prepared to take their place as co-equals with the other states in the Union. The United States could now expand, not as an empire with subject peoples and territory but by the orderly addition of new, sovereign states; and these states, in the words of the Ordinance, would be “on an equal footing with the original States in all respects whatsoever.”[24] At the Constitutional Convention, delegates approved Article IV, section 3, paragraph 2 of the Constitution which stated, “The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other property belonging to the United States.”[25]

So was the Articles of Confederation the major failure it has been known as? Well, maybe, but what was achieved here was worth the price of admission so to speak. It set the stage for an orderly growth of the American republic and ultimately secured the achievement of its destiny.

[1]William J. Watkins, Jr., Crossroads for Liberty (Oakland, CA: Independent Institute, 2016), 31.

[2]Farley Grubb, Founding Choices – American Economic Policy in the 1790s (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 261.

[4]The Library of Congress: Journals of the Continental Congress, June 22, 1778.

[5]Merrill Jensen, “The Cession of the Old Northwest,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 23, No. 1 (June 1936), 27.

[7]Watkins, Crossroads for Liberty, 32.

[10]Jensen, The Cession of the Old Northwest, 33.

[11]Virginia’s Cession of the Northwest Territory,www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/cessions.html.

[12]Grubb, Founding Choices, 263

[13]Robert V. Remini, “The Northwest Ordinance of 1787: Bulwark of the Republic,” Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 84, No. 1 (March 1988), 17.

[14]Grubb, Founding Choices, 259.

[15]Michael Toomey, “The State of Franklin,”northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/state-of-franklin/.

[16]Virginia’s Cession of the Northwest Territory,www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/cessions.html.

[17]Grubb, Founding Choices, 264, as discussed in Journals of the Continental Congress 19: 208-24.

[18]Jensen, The Cession of the Old Northwest, 48.

[19]Grubb, Founding Choices, 264.

[21]Remini, “The Northwest Ordinance of 1787: Bulwark of the Republic,” 15.

4 Comments

Excellent article, but there is one error which should be noted. The Northwest Ordinance, as originally passed by the Confederation Congress on July 13, 1787, ceased to be operative upon the adoption of the Constitution, and did indeed have to be relitigated. Accordingly, the First United States Congress passed legislation, on August 7, 1789, and with minor modifications so the Ordinance was made consistent with the Constitution, substantially affirming it. The Supreme Court, in Strader v Graham (1850), confirmed as much.

Got it. Thanks for clarifying. It’s a fine point but one I missed.

Enjoyed this thoroughly researched and well-presented piece. Simply want to mention, since the article does not, that Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Public Good, published in 1780, which argued that the western lands ought to be resolved by the Confederation Congress because after the Declaration of Independence these disputed lands no longer belonged to the states but to the new nation, played a role in helping resolve the impasse over the disposition of those lands. Virginia, of course, never forgave him and refused any efforts after 1783 to provide Paine with some remuneration for his services during the Revolution, even though it decided to give up its western land claims. Some believe Paine’s Public Good was a production by land speculators and that Paine’s pen was hired for their purposes. But it is interesting to note that one Virginian, who stood to lose plenty by Virginia’s decision, was one of Paine’s most ardent supporters after the war on behalf of Paine’s pleas for some sort of reward for his contributions.

Incidentally, Paine’s Public Good also called for a constitutional convention to remedy the defects of the Articles of Confederation, just as Alexander Hamilton did in the same year in a letter to James Duane. Both were written before the Articles were even ratified.

Should have mentioned in the previous post that the Virginian who had plenty to lose potentially by Virginia’s decision to give up its western land claims was George Washington.