“One of the most creditable actions of this war in which an American privateer was engaged took place on September 6, 1781.”—Edgar Stanton Maclay, A History of American Privateers

Comdr. Charles Stirling intently inspected the distant ship headed toward his command, HMS Savage, a sixteen-gun sloop of war cruising thirty-five miles off Charleston, South Carolina. It was early in the morning of September 6, 1781, and the other vessel was approaching from the east, so was not easily identified. Stirling estimated it was about four miles away when it turned into the wind as though pausing while it studied his own vessel, allowing him to identify it as American and probably a privateer. He saw that it was armed with twenty guns that he assumed were nine-pounders; Savage was armed with six-pounders so was outgunned by the privateer but Stirling commanded a Royal Navy vessel with a disciplined crew, partially offsetting his ordnance disadvantage. He decided to chase the vessel to bring her to action or drive her away since a convoy from England was expected at Charleston. The commander soon noticed that the privateer was not fleeing as he expected but was using its windward advantage to edge down on Savage, with the apparent intent to engage. Stirling brought his own ship into the wind to await the enemy. As the vessel approached, he saw it was armed with twelve-pounders rather than nine-pounders, giving it a two-and-a-half to one weight of metal broadside advantage. At that point Stirling decided to run for it in hopes a miscue by the privateer during a running fight would improve his position.[1]

The Privateer

The privateer encountered by Commander Stirling was the Philadelphia-built Congress, a brig carrying twenty twelve-pounder iron guns on her main deck and four six-pounder brass guns used as bow- and stern-chasers. At 450 tons she was one of the largest privateers launched at Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War and proved to be such a rapid vessel that even fast British warships could not catch her. Congress was in fact the size of a small British sixth-rate and was often described as a frigate. Her owners were a group of Philadelphia merchants led by Matthew and Thomas Irwin and Blair McClenachan, sponsors of numerous privateers throughout the war. Among those who purchased equity positions from the original owners was Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, whose correspondence provides useful insight concerning the privateer’s cruise.[2]

Congress’s captain was fifty-year-old George Geddis (or Geddes) who in 1779 had commanded the sixteen-gun privateer Holker for McClenachan. During two cruises he took eight prizes and provided the ship’s owners £1.1 million in profit. The first lieutenant was Richard O’Brien whose later career included a ten-year captivity in Algiers followed by service as consul-general there. Congress’s crew of 200 was the largest recorded for a Philadelphia privateer, reflecting the expectation that she would take numerous prizes requiring crews to take them to a safe port. Among her crew was a former Continental Army captain, Allen McLane, who commanded the ship’s marines, some of whom were also former Continental soldiers; they would figure prominently in the action with Savage.[3]

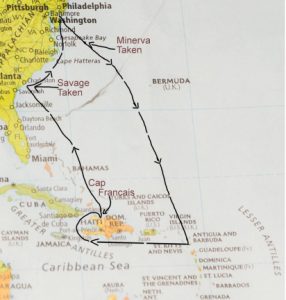

Congress sailed from Philadelphia about June 23, 1781, on a cruise to the West Indies that was planned to last four months. In the absence of a ship’s log the description of her cruise is based on the limited records kept by others. Within a few days she took the brigantine Minerva, bound from Tortola to New York, and sent the prize to Philadelphia. Congress continued to the Leeward Islands where she arrived about July 10. She had the bad luck to be there while Admiral Sir George Rodney’s fleet, split between Barbados and Antigua, was provisioning. That fleet included numerous frigates and sloops of war that patrolled the islands, providing security for prizes sought by the privateer. They recorded stopping and inspecting a number of neutral vessels including several Danish ships. One of these may also have been stopped and sent into Martinique by Congress before her neutrality was established. The privateer later reported to her owners that she “brought many vessels to” but took no prizes in the islands.[4] About the end of July she attempted to take a prize that escaped while attracting the attention of a British frigate that damaged Congress in “a sea fight.”[5] When the would-be prize arrived in New York she reported that Congress had been captured and taken into Antigua, not realizing that the privateer had used her superior speed to escape.[6]

Captain Geddis decided to sail to Cap Francais (today’s Cap-Haitien, Haiti) for repairs and reprovisioning on her way to a more promising cruising area. From the Leeward Islands Congress sailed south of Hispaniola then turned north through the Windward Passage, seeking prizes from the trade between Jamaica, the Bahamas, and North America. Instead on the afternoon of August 6 near the northwestern cape of Hispaniola Congress was intercepted by Actionnaire, a French sixty-four that was patrolling ahead of the French fleet under Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, comte de Grasse-Tilly. That fleet had departed Cap Francais on August 5 bound for the Chesapeake Bay. De Grasse left at Cap Francais over 160 French merchantmen awaiting convoy to France, protected only by harbor defenses, and wanted to satisfy himself that Congress was indeed an American privateer and not a British ship in disguise. Actionnaire escorted Congress to the flagship where Captain Geddis sent Lieutenant O’Brien and Captain McLane with the privateer’s credentials to meet with de Grasse. Following their successful “examination” by de Grasse the privateer was accompanied by Actionnaire to Cap Francais where they arrived August 8.[7]

Congress took on provisions and at least one crew member, a master’s mate, and repaired damage received in the Leewards. While at Cap Francais Captain Geddis wrote letters to the privateer’s owners and to the Continental Congress, the latter possibly to explain his interaction with the neutral vessel sent to Martinique. Soon after August 18 Congress departed Cap Francais for the coast of South Carolina where British-occupied Charleston attracted commercial traffic that included potential prizes. Two months into the cruise the privateer had taken only one prize and the frustrated Geddis was looking for more to justify her owners’ investment. Shortly after dawn on February 6 he sighted Savage.[8]

His Majesty’s Ship Savage

The Royal Navy warship Savage was a three-masted sloop of war of 302 tons that was commissioned in April 1778 as a fourteen-gun vessel requiring a crew of 125. Her bottom was copper-clad which would have given her a speed advantage over most similar vessels. By the time she sailed for North America the following year she carried sixteen six-pounders. Under her initial commander, Lt. Thomas Graves, she is perhaps best known for her April 1781 depredations in the Potomac River including the threat to Mount Vernon. Following Graves’ promotion into another ship, twenty-one-year-old Comdr. (and future Vice Adm.) Charles Stirling took command May 7, 1781.[9]

The new commander soon demonstrated his aggressiveness. One of his first actions was a July 15 surprise raid above Dobbs Ferry on the Hudson, when Savage captured the American sloop Magdalen. Continental and French artillery were waiting when she sailed down the river on July 19 and inflicted what they described as “considerable damage.” Savage had been repaired by early August when she sailed from New York for Virginia, probably carrying dispatches from Gen. Sir Henry Clinton to Lt. Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis. Off Cape Henlopen on August 4 Savage in company with several other British vessels took the American privateer Belisarius. After a brief call in Chesapeake Bay she continued on her way to Charleston, South Carolina and on August 9 took another prize, the American brigantine Two Sisters. She was patrolling the South Carolina coast to protect friendly shipping when Stirling sighted Congresson September 6.[10]

The Action

When Captain Geddis brought Congress into the wind early on September 6 it was for the purpose of evaluating an attack on what was plainly a British warship. With Congress’s superiority in firepower and crew size, Geddis knew he could capture the prize and expected it would be a valuable addition to the Continental Navy and thus lucrative for his owners; he decided to attack using tactics that should minimize damage. The weather was clear and the sea calm so he would approach the sloop’s quarter to allow his marines to pick off Savage’s crew. Then he would use his superior firepower to damage her sails and rigging while avoiding severe damage to her hull.[11]

Accordingly, as Stirling had observed, Congress turned downwind towards Savage. Despite the latter’s copper bottom she was slower than the privateer which drew within range; at 10:30 the privateer opened with her bow chasers as she approached Savage’s quarter. At 11:00 Congress’s marines began a musket fire that quickly killed Savage’s sailing master. This was followed by broadsides by both ships that, according to Sterling, took place at close range. After an hour of such fire Savage “was almost a wreck” in terms of her sails and rigging and she had become difficult to control. Stirling had not surrendered so at about 12:30 Congress dropped astern of Savage to allow Geddis to consider his next move.[12] His attempt to force surrender before Savage was heavily damaged had not worked so he would have to make use of his superiority in ordnance.

Congress came alongside Savage and mauled her with her ten twelve-pounders and all four six-pounders. According to Stirling, following this onslaught three of Savage’s eight guns were useless and nearly all the crew on the forecastle and quarterdeck were dead or wounded. With Savage’s mizzenmast shot away and her mainmast barely standing, and with Congress’s crew preparing to board Savage, Stirling struck his colors. The time was 14:45, the action having lasted over four hours. Savage’s losses were eight killed and twenty-six wounded and her damage such that five days were required to repair her sufficiently to make sail. Geddis’s attempt to capture Savage in good condition had foundered on Stirling’s determined defense, forcing him to use his overwhelming ordnance advantage to defeat her.[13]

Post Action

During the repairs to Savage, the privateer’s crew spent three days putting Congress into condition for sailing. Together the ships made sail for Philadelphia on September 11 but were sighted the next day by the British warship Solebay, a twenty-eight-gun frigate serving on the South Carolina coast. Solebay easily recaptured Savage on September 13 since despite repairs the latter was unable to carry sufficient sail to escape. She was taken into Charleston on September 22. Congress, with Commander Stirling and Savage’s crew on board, continued to Philadelphia where she docked on September 18.[14]

Many years later Edgar Stanton Maclay characterized the Congress-Savage action as “creditable,” that is, praiseworthy if not quite outstanding; that seems a proper assessment.[15] The victory of a privateer over a Royal Navy vessel, whatever the mismatch, certainly deserved praise. The victory might have been rated outstanding had it not come at such a high price: Congress lost eleven killed and thirty wounded and required further repairs after reaching Philadelphia. Defeating a warship had required the privateer to fight like a warship.

[1]Charles Stirling to Thomas Graves, September 23, 1781, The London Gazette, December 15, 1781; J. Ralfe, The Naval Biography of Great Britain (London: Whitmore & Fenn, 1828), 3:76.

[2]Bond of Thomas Irwin and George Geddis to Michael Hallegas, May 18, 1781, “Papers of the Continental Congress,” Ships’ Bonds, Letters of Marque, fold3.com; Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia), November 17, 1781; “List of Private Armed Vessels, to whom commissions were issued by the State of Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania Archives, Second Series, 1:366-375; Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714-1792 (St. Paul: MBI Publishing Company, 2007), 266; Charles Pettit to Nathanael Greene, August 23, 1781, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Dennis M. Conrad, ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 229. Measured tonnage values are provided for both vessels.

[3]William Bell Clark, “That Mischievous Holker: The Story of a Privateer,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 79 (1955): 28-35; Matthew Irwin to George Washington, July 9, 1789, Founders Online; Robert J. Allison, The Crescent Obscured(New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 154; Allen McLane Papers, New York Historical Society.

[4]Bill of sale of a share in the ship Congress, May 28, 1781, amended June 25, 1781, Miscellaneous Numbered Record 20555, U.S. Revolutionary War Miscellaneous Records (Manuscript File), 1775-1790s, Records Pertaining to Continental Army Staff Departments, Record Group 93, National Archives Publication M859; Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), June 30, 1781; New-York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury (New York), July 16, 1781; Captain’s log of HMS Convert, ADM 51/207, entry for July 7, 1781, National Archives, London; Conrad, Nathanael Greene Papers, 229.The circumstantial evidence that Congresssent a neutral vessel into Martinique is as follows: Soon after Congress arrived in the Leeward Islands, Samuel Parsons, the unofficial U.S. agent in Martinique, addressed two letters to the Continental Congress that were received soon after a letter written by Captain Geddis. Parson’s letters were “referred to the committee on the letter of 18 August from G. Geddes.” The privateer captain would probably only have written the Continental Congress to defend a violation of his letter of marque terms such as interfering with a neutral vessel. See Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1912), 21:944, 968.

[5]Allen McLane Papers. Logbooks of frigates and sloops of war known to have been in the Leeward Islands at this time do not mention an action with an American privateer so the encounter with Congress was minor, that is, in the category of “fired several shots at the chase.”

[6]New-York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury (New York), August 27, 1781; Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), September 12, 1781.

[7]Conrad, Nathanael Greene Papers, 229; Navigation Journal of the Fleet under the orders of M. Comte de Grasse, entries for August 5-8, 1781, MAR/B/4 Fonds de la Marine, Service general, campagnes, National Archives, Paris; Journal of Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, Francisco Morales Padron, ed. (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1989), 200, 209-210; Karl Gustaf Tornquist, The Naval Campaigns of Count de Grasse (Philadelphia: Swedish Colonial Society, 1942), 49; Allen McLane Papers. In the last reference McLane recalled this “examination” and added that he “gave it as his decided opinion” that de Grasse should take his fleet to Chesapeake Bay to assist the Continental Army. De Grasse had made that decision about July 18 but was not likely to have discussed it with a stranger since he did not tell his own officers their destination until off Havana on August 18. See John G. Shea, The Operations of the French Fleet under the Count De Grasse in 1781-2 as Described in Two Contemporaneous Journals (New York, 1864), 63.

[8]Conrad, Nathanael Greene Papers, 229; Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), October 6, 1781; Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1912), 21:944.

[9]Winfield, British Warships, 281, 283-284; The Revolutionary Journal of Baron Ludwig von Closen 1780-1783, Evelyn M. Acomb, ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1958), 97; “‘Burnt All Their Houses:’ The Log of HMS Savage during a Raid up the Potomac River, Spring 1781,” Fritz Hirschfeld, ed., Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 99 (1991), 513-530; Dictionary of National Biography, 1898 edition, s.v. “Stirling, Sir Walter.” Savage’s log for September 1781 has not been located and probably no longer exists.

[10]Royal Gazette (New York), December 1, 1781; Captain’s log of HMS Amphitrite, ADM 51/10, entry for August 3, 1781, and Master’s log for HMS Medea, ADM 52/2398, entry for August 3, 1781, National Archives, London. Savage was probably carrying Clinton’s August 2 letter to Cornwallis.

[12]Ibid. Stirling said that “accident obliged [Congress] to drop astern” and that she lay “directly athwart our Stern for some minutes.” Whether accidental or deliberate, Geddis used the time to change tactics and to prepare boarding parties.

[14]Ibid.; Captain’s log for HMS Solebay, ADM 51/4345, entries for September 12 and 13, 1781, National Archives, London; The Royal Gazette (Charleston), September 22, 1781; Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), September 19, 1781.

[15]Edgar Stanton Maclay, A History of American Privateers (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1899), 211. Congress’s losses are from Stirling’s account since as a prisoner on the privateer after his surrender he could observe the results of the action. Other sources give Congress’total losses ranging from twenty-five to forty.

2 Comments

Thank you for this article. I live in Charleston so next time I look at the ocean I’ll remember this exciting story. I have a question on the recapture of the Savage though. Instead of letting the Brits recapture the Savage, could the Americans have put prisoners to lifeboats and scuttle the ship thereby denying the enemy the prize? Thank you for any insight you may offer.

Response to question by Jim Poch: Jim, HMS Savage carried a small prize crew from the privateer Congress (which took the British crew as prisoners to Philadelphia) and they had no quick method of scuttling Savage when HMS Solebay threatened (no Kingston valves as in more recent vessels). A month later at Yorktown, the British scuttled HMS Fowey by drilling holes in the hull, which probably took more time than was available to the Savage’s prize crew. Bill