William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin, was the last Royal Governor of New Jersey, from 1763 to 1776. He is usually identified in U. S. History texts negatively as an ardent Loyalist and opponent of the American War of Independence. Historian Larry Gerlach offers a different view: “He was one of the most popular and successful of all royal governors, effectively representing both the crown and the people of New Jersey from 1763 to 1776.”[1] One area of his administration that is overlooked is his actions in 1766 seeing that justice was afforded to Native Americans in New Jersey.

William Franklin took office after the French and Indian War and during Pontiac’s Rebellion. Those events stirred up increased hatred for Native Americans throughout the Colonies and led to several atrocities directed towards them regardless of whether they had participated in attacks on settlers or they were non-belligerents. These acts of violence took place with disregard to the overall policy of the British Government to treat the Native American population with equanimity.

In 1766 two crimes were perpetrated against Native Americans in New Jersey that reflected this hatred: the murder in northwestern New Jersey (Sussex County) of a visiting member of the Oneida tribe; then the murder of two Lenni Lenape women who lived in Burlington County. In both cases, Governor Franklin, as the representative and chief law enforcement officer of the Crown, oversaw the capture, trial, and execution of the murderers. One result of his actions in these incidents occurred at the 1768 signing of a treaty with Native Americans at Ft. Stanwyck, New York, when an Oneida chief bestowed upon William Franklin the honorific “Sagorighweyoghsta” (Great Arbiter or Doer of Justice).[2]

William Franklin, born in Philadelphia in 1730, began life with a handicap: he was referred to as Benjamin Franklin’s “illegitimate son” and it was to be used as a slur on his character throughout his life and political career.[3] Deborah Read, Franklin’s common-law wife, raised William; she also had two children by Benjamin: son Francis Folger, born in 1732 but died of smallpox in 1736, and daughter Sarah (known as Sally) born in 1743.

Starting in 1750, Benjamin and William both agreed William would study law. He was apprenticed to a noted Philadelphia lawyer Joseph Galloway and Benjamin went so far as to secure William a future place at the Inns of Court in London where British lawyers studied to hone their skills.[4] At this time, Benjamin Franklin’s political career was in its ascendancy, plus his reputation as a scientist and philosopher was also enhanced. It seems William was happy to benefit from the success of his father, accepting several positions with the colonial government through Benjamin’s influence. It was during this period that William fell in love with Elizabeth Graeme, the daughter of Dr. Thomas Graeme, and they planned to marry.[5] The relationship was opposed by her parents but this did not deter the young couple’s plans. The relationship, however, came to an end when William accompanied his father to England in 1757.

Benjamin Franklin had been sent to England as a representative of the Pennsylvania Assembly opposing the Proprietary rule of the Penn Family. After William completed his legal studies, both Franklins proceeded to tour throughout the British Isles, meeting with some of the most influential men both in and out of the government. Evidence suggests that William didn’t devote all his time to his duties as personal secretary to his father; in 1760, an “unknown woman” presented him with a son, William Temple. Then in 1762 momentous changes occurred: Benjamin returned to America in August, William married Elizabeth Downes on September 4, and on September 9 he was named governor of New Jersey.[6]

When William Franklin arrived in New Jersey in 1763, unlike neighboring colonies, it had not been affected by hostile Native American actions in Pontiac’s Rebellion. While the intense fighting between English settlers and the Native Peoples occurred mainly in Trans-Appalachia (Ohio Country), it ingrained in many Anglos an intense hatred of all Indians. Historian Clinton Weslager notes:

Many friends or relatives of persons who had been massacred or taken into captivity by Indian war parties—particularly those who saw the mutilated bodies of loved ones lying in the smoldering ashes of burned homes—became “Indian haters” and sought reprisal. They called Indians “dogs” and “thieves” and cursed them to their faces.[7]

An example of this attitude toward all Native Americans was manifested in the actions of a group of Pennsylvanians who became known as the “Paxton Boys.” They murdered a group of Native Americans referred to as “Praying Indians” near Lancaster, Pennsylvania in1763.[8]

The first murder of a Native American during Franklin’s time in office occurred in April 1766. Governor Franklin described the murder in a Proclamation:

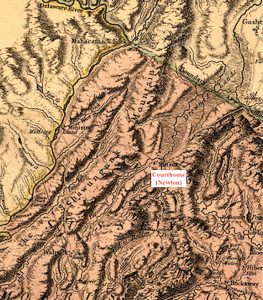

Whereas I have received Information from one of the principal Officers of the County of Sussex, that a most inhuman Murder and Robbery has been lately committed near Minisink, on the Body and Effects of an Indian of the Oneida nation, who had come there to trade, and had behaved himself soberly and discreetly; and that one Robert Simonds, alias Seamonds, had been charged with the same was on the second day of April Instant committed to the common Goal of the County aforesaid.[9]

The Oneida were part of the original Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy—Mohawk, Oneida, Onondagas, Cayuga, and Seneca (in 1722 a sixth was added, Tuscarora)—that controlled much of what became New York state and the Great Lakes region. Throughout the colonial wars between the French and English, the Iroquois, for the most part, remained, neutral. During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), under the influence of Sir William Johnson, the British Indian Agent in the north who had been adopted by the Mohawks, the Mohawk and Oneida took active parts in the war on the side of the English. The killing of a friendly Oneida caused consternation to those who wished to continue friendly relations with the Iroquois.[10]

Two men, Robert Seymour and David Ray, were suspected of the murder. Seymour was described as a “base Vagabond fellow” who had deserted from the British Army.[11] He was arrested for the crime and taken to the Sussex County Jail located in the county seat, Sussex Courthouse (today Newton, New Jersey). Locals in Sussex broke him out of jail and he was hidden by his neighbors who threatened harm to anyone who tried to turn him in to the authorities. This reaction by residents eventually emboldened Seymour to come out of hiding and resume his normal life as a farmer.[12] To help bring Seymour to justice, Governor Franklin stated:

I do promise, that the Person or Persons who shall after the Date hereof, who shall apprehend the said Robert Simmonds alias Seamons or any Person guilty of the Murder and Robbery aforesaid, shall, upon conviction of the Offender, receive from the Treasury of this Province, ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS Reward.[13]

Answering the order to rearrest Seymour, the Sheriff replied that it was useless to do so becasue no Sussex County jury would convict him. Franklin then ordered the Sheriff of neighboring Morris County to arrest Seymour and asked the Provincial Legislature to change the venue of the trial, which they refused. As a result, the Sussex magistrates refused to call a special court into session; instead they would wait the five months until the Provincial Circuit Court came there. Being rebuffed by local authorities, Franklin appointed a Court of Oyer and Terminer under Charles Read,[14] who held the trial in Sussex County and invited Native American observers.[15]

Although the murder occurred in April it wasn’t until December 18, 1766, that a grand jury indicted Seymour on the charge of murder and David Ray for manslaughter. Ray decided to ask for the “benefit of clergy” and pled guilty. His punishment was to be branded on the hand and then released.[16] As for Seymour, despite witnesses attesting that he admitted his crime and declared “he would destroy any Indian that came in his way,” he wanted his case to go to trial.[17] A description of Seymour’s actions, given at the trial, was quite vivid:

The evidence against him was—His Behavior to the Indian before they went together from the House, his being possessed of the Indian’s Gun and Goods, Proof that he broke the back and Legs of the dead Body, and buried it, that he confessed the Murder to some Witnesses and declared he would destroy any Indian that came in his Way. He challeng’d several of the Jury, denied the Fact, and said he bought the Goods found on him, of a Sailor.[18]

Seymour was found guilty but he believed that he would be freed again like he was when he was originally arrested. Governor Franklin, anticipating this possibility, ordered twenty-five militiamen to guard the prisoner night and day. A newspaper account described Seymour’s last hours:

The next Morning he was brought to the bar, and sentenced to be executed between three and four that Afternoon, at which time he was brought out, strongly guarded by Detachments from adjacent Companies of Militia–He appeared dismayed—at the Gallows, made a short Prayer, declared that he lived a very wicked Life, and was Guilty of the Fact for which he was to suffer: He was then executed.[19]

Of the Oneida observer at the trial, the Governor stated:

An Indian of Note, of the Oneida Nation, had with some Difficulty been prevail’d upon to attend the Trial, from the first to last—he was respectfully treated, and appeared highly satisfied with the Justice of the Proceeding, which he said should represent to his Brethern.[20]

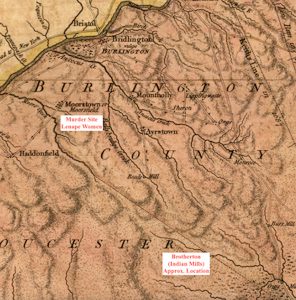

The next murder of Native Americans in New Jersey took place in June 1766 in Burlington County. As troubling as the murder of a visiting Oneida trader in Sussex County was, the murder of two local Lenni Lenape women was viewed as even more heinous.

The native people who originally lived in what was to become New Jersey were the Lenni Lenape (“true men” or “original people”); they were also known as the “Delaware,” a name given to them by English settlers.[21] The Lenape were an Algonquin-speaking people who lived in what is today southern New York, through eastern Pennsylvania, all of New Jersey and Delaware, south to Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The Lenape were not a single tribe under one chief; rather they were three distinct groups who spoke different dialects: the Munsee in the North, Unami in the Central Region, and the South, Unalactgio. Overriding these dialect groups were three matrilineal clans that were found in all of the regions: Turtle, Wolf, and Turkey, with the Turtle Clan having the most influence. It has been estimated that pre-European settlement there were about 20,000 Lenni Lenape.[22] Through decimation from inter-tribal warfare (with the Susquehannock and the Iroquois Confederation), followed by the introduction of European diseases, mainly small-pox, by the start of the eighteenth century they numbered about 4,000.[23]

As European settlement encroached on Lenape land in New Jersey many began to move west to the Pennsylvania area between the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers. Others moved farther west to the Ohio Valley area joining the Miami Confederation. Throughout this migration period, the Lenape continued to cede more and more land in New Jersey to the Europeans so that by 1750 no more than 200 to 300 Lenni Lenape in New Jersey remained living in a tribal group setting, or on their farms or near towns, usually having friendly relations with their European neighbors. As Clinton Weslager described the situation:

Although there had been a series of movements of New Jersey Indians across the Delaware river—to settle in the Forks at Easton, Pennsylvania, to affiliate with the Moravians at (the first) Gnadenhutten, and later to join other migrants at Shamokin and Wyoming—a small group of Delawares clung tenaciously to their New Jersey homes. They no longer resided in villages but were scattered in rural areas, a few families had their own cornfields and vegetable patches. Perhaps they owned a horse or a few pigs, and some raised chickens. They fished and crabbed in season, some made splint baskets, brooms, cornhusk mats, and wooden bowls, and peddled them from door to door.[24]

Sadly, these benign relations took a turn for the worse with the coming of the French and Indian War.

In 1755 some of the Lenape who emigrated from New Jersey sided with the French and began attacking settlements in northeastern Pennsylvania between the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers, with a few incursions into northwestern New Jersey. While the majority of European residents in central and southern New Jersey were in no danger from Indian attacks, with continued stories of “Indian massacres” they became suspicious of local Lenape. By 1756 the suspicion of the motives of local Lenni Lenape went so far that Gov. Jonathan Belcher joined with Pennsylvania and offered a bounty for the scalps of “hostile Indians.”[25] Eventually, with the French prospects for victory over the English in the decline, relations between the Lenni Lenape and New Jersey’s government were settled with the 1758 Treaty of Easton in which the Lenni Lenape basically ceded all “tribal” land claims in the colony.[26] This led to the purchase of a large tract of land in Burlington County that became the first “Indian Reservation,” known as Brotherton.[27]

Moving ahead to June 1766 in relatively peaceful Burlington County, the New York Journal or Weekly Post Boy recorded:

Burlington, in (N. Jersey) July 3, 1766, Two Indian Women were barbarously murdered a few Days ago, at Morristown [sic, Moorestown], in this County, by two Scotch-Irish strollers. One of the Murderers, named James Anin, was committed to our Gaol, the Night before last, the other, James M’Kensie, is not yet taken.[28]

The attack and murder occurred on June 26, 1766. The victims were two Lenni Lenape women identified as Catherine and Hannah, “who had long resided in the neighborhood of the place where the murder was committed.”[29] The two men identified as “Scotch-Irish strollers” James Anen (aged fifty-four) and James McKinsey (aged nineteen) both had spent time on the Pennsylvania and Virginia frontier regions, an area that experienced a good deal of brutality during the warfare associated with the Pontiac’s Rebellion. Supposedly the younger man, McKinsey, had been the servant of a “Scotch” officer killed at Pittsburgh. Anen and McKinsey had met in Philadelphia and decided to travel to New York together, where McKinsey hoped to meet with the widow of his deceased master.[30] Over the next month, newspaper accounts what happened next.

The two perpetrators arrived in the Moorestown area where they “begged for charity.” While they were eating, the two Lenape women came to the same place. The “youngest of the men gave them abusive language.” The women went into nearby woods where they rested; one of them had a “clean shift” and the other a “new piece of linen” they bought that day. They were seen laying near the road and it was supposed they were asleep. Three days later, Sunday, June 29, “two persons perceived the stench, and on going near the bodies found that they were dead; whereupon the coroner was called, whose inquest found them to be murdered by persons unknown.”[31] Anen and McKinsey became the chief suspects when it was recognized that “Anen sold the shift and McKinsey the piece of linen about two miles from Moorestown” on the last day the women were seen alive. An alarm went out. Anen was apprehended and sent to the Burlington jail; McKinsey fled back to Philadelphia but was soon arrested and returned to Burlington. Each man stated that the other was the one who committed the murders.[32]

They were indicted and a court of Oyer and Terminer was held in Burlington on July 30. In the indictment it was noted that both men stated that they went over to the women “with the intent to ravish them if they refused their offer.” Both admitted being present at the murders and taking the women’s goods, but each continued to maintain it was the other “giving the stroke.” The jury found them both guilty and they were sentenced to death by hanging. The execution took place on Friday, August 1, 1766.

When led to the gallows, the murderers provided more details of their crimes, but each man continued to blame the other. Anen “thought it a duty extirpate the heathen.” McKinsey claimed that both women were knocked down by Anen, but “one of the Indians, on receiving the blow from Anen, struggled violently,” so McKinsey “to put her out of her pain, sunk the hatchet in her head.” A newspaper account added, “The youngest of the squaws was near the time of delivery and had marks of shocking treatment which the most savage nations on earth could not have surpassed.” To demonstrate that justice was done, “A few of the principal Indians in Jersey were desired to attend the trial and execution, which they did, and behaved with remarkable sobriety.”[33]

The murders of these Native Americans in New Jersey attracted the attention of the British government. The Earl of Shelburne (William Petty) was the Secretary of State for the Southern Department that included the American Colonies. In a letter dated September 13, 1767 to Governor Franklin he wrote “that the most unprovoked violences and Murthers have been lately committed on the Indians, under the Protection of His Majesty, and whose Tribes are at Peace and Amity with His Majesty’s Provinces and that the offenders have not yet been discovered and brought to Justice.” Further, Shelburne ordered Franklin “that you apply yourself in the most earnest manner to remedy and prevent those Evils, which are as contrary to the Rules of good Policy as of Justice and Equity.”[34]

On December 16, 1767, Governor Franklin wrote a reply to Lord Shelburne detailing the actions he took to apply “Justice and Equity” with regards to the murders:

In answer to your Lordship’s Letter of the 13th of September, relative to the Violences & Murthers which have lately committed on the Indians under the Protection of His Majesty, I can assure you Lordship that whatever may be the Case in the other Colonies nothing of the kind has been suffered to pass with Impunity in this Province. . . .There has been lately two Persons executed here for the Murder of two Indian Squa’s, belonging to a small Tribe settled in the interior Parts of the Province, on Lands given them by the Publick.[35]

Franklin went on to describe the background of the perpetrators, noting that they “were not inhabitants of the Colony” and that he “omitted nothing in having the Villains apprehended.” He further explained how the murderer of the Oneida in Sussex County was arrested and would be dealt with appropriately.[36]

Governor Franklin continued in this letter to give an overview of how he dealt with Indians in these instances:

These are only two Affairs of the kind which have happened in this Province during my Administration; & I hope these Instances of Attention and Regard to the Indians will prove an Advantage to the British Interest with them, as well as of Service to those Colonies where they have not met with the same Justice.[37]

He added that of all the colonies New Jersey probably had the least amount of dealings with Indians “as they do not pretend any and Claim to Lands within our Limits, and we have no Trade or Intercourse with them except now & then.”[38]

His last words on the subject of the Indian murders were in a letter to Shelburne dated December 23, 1767:

I have this Moment receiv’d a Letter from Judge Read, whom I sent into the County of Sussex, with a Special Commission of Oyer & Terminer to try one Seamour, the Supposed Murderer’ of the Oneida Indian, in which he informs me, That he procured Indians to attend the Trial, and that Seamour was convicted and executed, a Detachment of the Militia attending the Execution to prevent a Rescue.[39]

Franklin summarized his attitude toward Native Americans in New Jersey by ending his Proclamation dealing with the murder of the Oneida with the following admonition:

And I do likewise in the most earnest Manner recommend it to the Inhabitants of this colony, to behave with Kindness, Humanity, and Justice, to such Indians who shall visit the Frontiers in a friendly Manner, as such a Conduct will have a tendency to perpetuate the Blessings and Advantages of Peace.[40]

Gov. William Franklin’s actions in applying justice in these cases of murders of Native Americans in New Jersey have been looked upon by historians as almost unique in the British colonies. Marshall Becker summarizes Franklin’s resolution of dealing with the murders:

The murders seem to have been prompted by greed spurred on by racism, rather than being related to contemporary military activities. That the perpetrators of these deeds were swiftly apprehended, tried and hanged may reflect the colonial government’s commitment to justice for Native American inhabitants of New Jersey.[41]

Further, Alden Vaughan sees that Governor Franklin’s actions in bringing justice to Native Americans were different than in the other British Colonies:

New Jersey’s handling of the two murder cases in 1766 demonstrated that not every colonist wanted to exterminate the Indians and that colonial courts on rare occasions administered impartial justice, the baneful shadow of the Paxton Boys did not reach every corner of British America. But New Jersey’s record was atypical.[42]

Governor Franklin’s actions in seeking and obtaining justice for Native Americans in these two cases justify the title “Sagorighweyoghsta” bestowed upon him by the Oneida.

[1]Larry R. Gerlach, “William Franklin: New Jersey’s Last Royal Governor,” New Jersey’s Revolutionary Experience, no. 13 (Trenton: NJ Historical Commission, 1975), 5.

[2]“Ratified treaty # 7: Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768,” Edward O’Callaghan, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, vol. 8. (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons, and Co.,1857), 132.

[3]For discussions on who his mother was and the effects of his illegitimacy see: Sheila L. Skemp, “William Franklin: His Father’s Son,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 109 no. 2 (1985), 145-78; Charles Henry Hart, “Who Was the Mother of Franklin’s Son. An Inquiry Demonstrating That She Was Deborah Read, Wife of Benjamin Franklin,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 35 no. 3 (1911): 308-14.

[4]Gerlach, “William Franklin: New Jersey’s Last Royal Governor,” 11. Franklin was admitted to the Bar of the Middle Temple, November 1758.

[5]Elizabeth Graeme was a noted American poet. For a brief review of this amazing woman’s life see: History of American Women—Colonial Women, www.womenhistoryblog.com/2009/01/elizabeth-graeme-fergusson.html.

[6]Elizabeth was the daughter of a wealthy Barbados sugar planter.

[7]Clinton A. Weslager, The Delaware Indians: A History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1972), 247.

[8]For an excellent review of the role of the Paxton Boys, see Alden T. Vaughan, “Frontier Banditti and the Indians: The Paxton Boys’ Legacy, 1763-1775,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 51 no. 1 (1984): 1–29.

[9]“Extracts from American Newspapers to New Jersey,” vol. VI, 1766-1767, in Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, vol, XXV, First Series, William Nelson, ed., (Paterson, NJ; The Call Printing & Publishing Co., 1903), 91-93.

[10]For an excellent overview of the history of the Iroquois see Paul A. Wallace, “The Iroquois: A Brief Outline History,” Pennsylvania History, Vol. 23, no. 1 (January 1956), 14 -28.

[11]Alden T. Vaughan, “Frontier Banditti,” 15. Governor Franklin referred to him as Simonds or Seamons; in a number of present-day histories he is known as Robert Seymour. The governor did not mention the second person believed to be involved in the murder, David Ray.

[13]“Extracts from American Newspapers,” 94. No mention if anyone ever received the reward.

[14]Charles Read was the secretary for the governor and the legislature; also, he was a judge on the Provincial Supreme Court. For a brief biography of this influential individual, see: J. Granville Leach, “Colonel Charles Read,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 17, No. 2 (1893), 190-194.

[15]The Court of Oyer and Terminer functioned as the court of general jurisdiction in serious criminal cases—i.e., those which required an indictment or presentment for the Crown to proceed. See: George C. Thomas III, “Colonial Criminal Law and Procedure: The Royal Colony of New Jersey 1749-57,” NYU Journal of Law and Liberty, vol. 1, no. 2 (2005), 672.

[16]Asking for the “benefit of clergy” was part of British Common Law that allowed a first-time defendant to be spared execution for a capital crime. Also, in Colonial British America, a person convicted of manslaughter who was spared execution was branded with the letter M. See: Benefit of Clergy, www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1250.html.

[17]“Extracts from American Newspapers,” 92-93. In all the newspaper accounts and histories of this event, the murdered individual’s name was never given, he was only identified as an “Oneida.”

[18]“Extracts from American Newspapers,” 271.

[21]The Delaware River was called by the Native Americans Wihittuck; in 1610 Samuel Argall, on an exploring expedition, named the bay and river after the then governor of Virginia, Thomas West, Lord De La Warre. Today tribal groups in various states refer to themselves as “Delaware Nation.”

[22]Jean R. Sunderal and Claude Epstein put the pre-European Lenape population at 12,000. “Lenape—Colonial Land Conveyances in West Jersey: Evolving in Space and Time,” New Jersey Studies (Summer 2018), 186.

[23]See:Native Americans: Lenni Lenape, Penn Treaty Museum, www.penntreatymuseum.org/americans.php#lenapehistory. The article states from latest census data the number of Lenni Lenape (Delaware) is back to the 20,000 number, with largest concentration in Oklahoma.

[24]Weslager,The Delaware Indians, 261.

[25]“Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey, Vol. IV 1756-1761,” Documents of Relating to the Colonial History of New Jersey, Vol. XX, William Nelson, ed., (Patterson, NJ: Call Pub. & Printing, 1898), 39-41. On July 26, Belcher rescinded the bounty on Indian scalps.

[26]For what transpired at the Easton Conference see: “The Minutes of a Treaty held at Easton, in Pennsylvania, in October, 1758,” Evans Early American Imprint Collection, quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N06429.0001.001/1:2.11?rgn=div2;view=fulltext.

[27]For an overview of the Brotherton Reservation see: “Passing of the Indians,” XVI, Moorestown and Her Neighbors—West Jersey History Project, www.westjerseyhistory.org. Today the Brotherton Reservation is known as Indian Mills, Shamong Township, Burlington County.

[28]“Extracts from American Newspapers,” vol. VI, 160. In the articles dealing with this incident the names of the accused were spelled in various ways; the consensus of the correct spelling was James Anen and James McKinsey. On July 17 a correction was published that the murders took place near Moorestown, not Morristown.

[29]“Pennsylvania Gazette, August 7, 1776,” Extracts from American Newspapers, 184 -185. The description of the events of the murders and the events surrounding them are mainly from this article.

[30]Extracts from American Newspapers, 159.

[34]“Shelburne to Franklin, Sept. 13, 1767,” Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, vol. IX, 1757 -1767, Fredrick W. Ricord and William Nelson, editors, (Newark, NJ: Daily Advertiser Printing, 1885), 570. Shelburne mentioned that he received the reports of the murders from “Superintendent of Indian Affairs,” who was Sir William Johnson.

[35]“Letter from Franklin to Shelburne Dec. 16, 1767,” ibid., 575.

[40]“Extracts from American Newspapers to New Jersey,” 94.

[41]Marshall J. Becker, “A New Jersey Haven for Some Accultured Lenape of Pennsylvania During the Indian Wars of the 1760s,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 60, No. 3 (July 1993), 334.

[42]Vaughan, “Frontier Banditti,” 17.

2 Comments

Excellent and interesting article regarding Gov. William Franklin and his dealings with murders of Native Americans in New Jersey. This is to me that type of information that history buffs need to know and is rarely published. William Franklin deserves to be know for his actions as governor in New Jersey and not for being Benjamin Franklin’s Tory son. Thanks Joseph for your research and writing.

On of the best articles I have read in a while. It brings some very important information about William Franklin to the public, information that needs to be included in any real and honest assessment of William Franklin’s career and life.