It is generally taken for granted that France was ready to jump into the war between Britain and the rebelling North American colonies on the side of the colonies as soon as the colonists showed themselves capable of giving the British a serious fight. After all, Britain had been a frequent antagonist to France, had recently humiliated France during the Seven Years War, and its relative power was steadily growing. Setting aside the differences of opinion between Turgot and Vergennes within the French court, which we will return to, this perspective misses the fundamental contingency of the circumstances that even allowed France to consider intervening efficaciously in the American Revolution. The French motivation for helping the Patriots being obvious, French assistance, key in securing the final victory at Yorktown, was only possible because of a singular window of relative peace in Central and Eastern Europe during the latter half of the eighteenth century. For no matter the strategic advantages France might have hoped to gain from effectively intervening in the conflict between Great Britain and its North American colonies, they would have been unable to devote adequate resources to the distant conflict had there not been relative peace between Russia, Prussia, and Austria during the period 1775-83.

Making this case requires a basic understanding of the basic trajectory of European great-power relations in the eighteenth century, the causes and consequences of the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, and the consequences of these and local events in Central and Eastern Europe, along with a description of the strategic landscape facing each of the great powers as the American Revolution got under way. For our purposes, these were, in no particular order, Russia, Prussia, Austria, France, and Great Britain—though the Ottoman Empire was also a factor.

Before turning to the anatomy of the French state to understand its increasingly deficient war-making capabilities, the broader landscape of the European great-power balance in the eighteenth century must be described. How the perpetual conflict and strategic posturing between the French Bourbons and Austrian Habsburgs was put uncomfortably to rest during the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 can be easily understood by tracing the arc of conflict over the first half of the eighteenth century and appreciating the different priorities and strategic challenges each power had and perceived. For, to paraphrase Lord Palmerston: States have no permanent friends, only permanent interests. As the relative capabilities of states change over time so too do each of their perceived interests and perceptions of their local threat environment.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century France was allied with the Ottomans, Swedes, and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This alliance structure, created by Louis XIV to check Austrian power, was destroyed, in large part, by the rise of Russia. The Czar’s armies defeated the Swedes in a series of wars at the start of the eighteenth century and eventually took part in the dismemberment of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Over the same period, just as England was being fiscally and institutionally reorganized in a way that henceforth made it a serious global imperialist contender, Prussia’s Frederick I instituted modernizing military reforms that made the already-centralized Prussian state formidable on the Continent in its own right. Its rise helped erode the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as well and further alarmed Vienna, already concerned by the growing strength of Moscow. As for the Ottomans, increasingly starved of trade revenue by global shipping and beset by increasing internal dissension, their power had already peaked, and numerous defeats at the hands of Austria and Russia made it an increasingly marginal player in European geopolitical considerations.

This instability resulted in serial alliance-switching in the decades prior to the American Revolution as the relative stability of the seventeenth century, defined by the struggle to prevent Habsburg dominance over the Continent, was eroded by the emergence of Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia as great powers. Thus, the conflicts of the eighteenth century resulted from what international relations scholars call “transitional friction.” The spheres of influence claimed and recognized by the existing great powers, Austria and France, came to be critically challenged by the newly emerging great powers who sought various changes to the status quo. This struggle between the hitherto dominant but rival powers to preserve their individual interests while variously fending off or accommodating the different claims of Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia ultimately led to the unlikely outcome of the long-time antagonists being joined together against the upstart powers after the First Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1756.

That was the direct, if drawn out, result of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), which had enhanced relative Prussian and Russian power. Austria, fearing itself exposed and in a weakened state, sought alliance with France at war’s end. This was in part because Britain had quickly switched sides to the Prussians. But France, for its part, did not wish to see Austria further weakened by British-backed Prussian incursions, as it increasingly viewed Austria as an essential buffer between it and the looming Russian colossus. And while the alliance forged in 1756 did critically buttress the Austrians, creating the conditions for the later period of relative peace in which the French Monarchy intervened in the American War for Independence, it cost France dearly in the second of the two major conflicts of the period, the Seven Years War (1756-1763), with the defeat of its coalition at the hands of British-American colonial forces spelling its eviction from the North American continent over a Prussian invasion of Austrian-held Silesia.

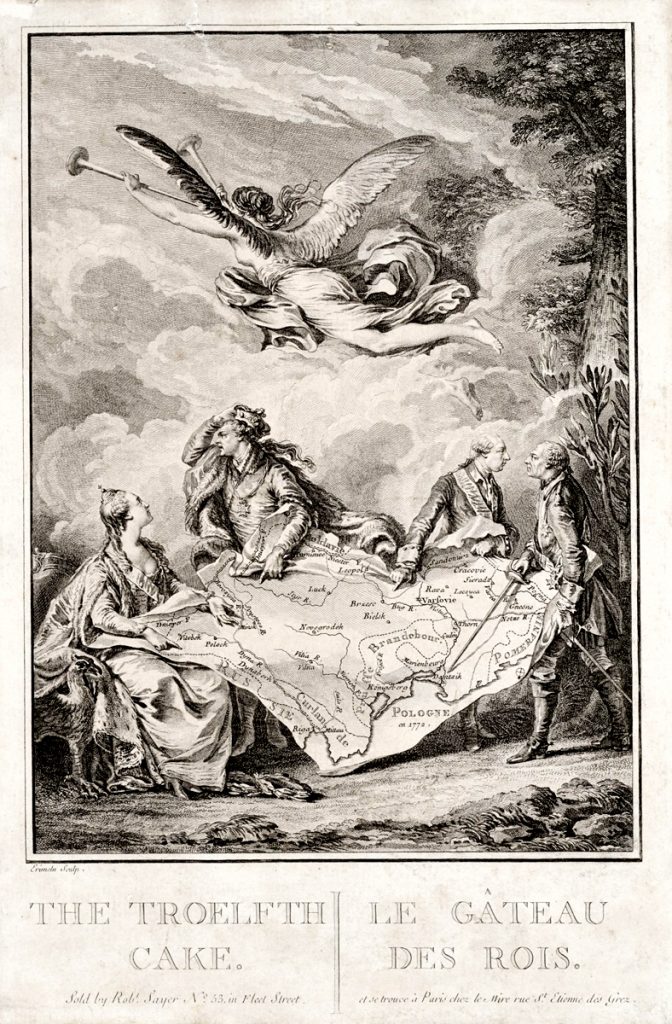

The years between the Seven Years War and American Revolution were filled by the Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774). It led to further Russian gains, and critically fueled further Austrian fears. It was under these proximate circumstances that the first partition of Poland, 1772, was decided between Austria, Russia, and Prussia as a way of satisfying the security concerns and territorial claims of each while allowing for a break in great power hostilities between them. So it was that on the eve of the American Revolution, France had open before it a window of several years in which it might undermine the upstart British position across the Atlantic without fear of having to critically divide its resources in a costly land campaign against a coalition of its easterly great power neighbors.

In each of their conflicts of the prior two decades, France had been required to fight Britain and its various allies on multiple fronts and had suffered for it. The basic problem was the still essentially feudal nature of the French state, whose limited fiscal capabilities and relative financial immaturity prevented it being able to effectively fund large armies and a commensurate navy simultaneously for long periods. Unlike Britain, which following the Glorious Revolution had undergone the fundamental centralizing institutional changes necessary to the state’s ability to sustain the large amounts of debt increasingly required to wage early modern industrial war (a rationalized and professionalized state, revenue collection, central bank, and developed credit markets), France under the Ancien regime was still rife with internal barriers to trade, with tax exemptions for the nobility and Catholic Church, was reliant on the sale of offices for revenue, and lacked a central fiduciary apparatus or good credit rating. Indeed, until the Swiss-born French Finance Minister Jaques Necker set about compiling his famous, or infamous, Compte rendu in 1781, wherein he outlined his assessment of state finances, there had been no centralized accounting of total French debt as such. Consequently, the French state faced twice the borrowing costs Britain did over the same period.

In an age of increasingly capital-intensive warfare, France’s continuing deficiency in revenue collection and financial capability translated directly into military disadvantage; and so while the French Foreign Minister of the period, the Comte de Vergennes, correctly perceived the geostrategic opportunity environment created by the revolt of Britain’s North American colonies, he should have listened to his colleague, the early economic liberal Jacques Turgot, briefly Minister of the Navy. Turgot correctly cautioned that, even though temporarily freed up to their east, French state finances could not bear the strain of yet another extensive exertion. Indeed, though the British would ultimately give up the fight, the drain on French resources during the few years it was involved was crippling, coming as it did atop the already staggering amounts of debt undertaken by the French Crown over the course of the previous four decades of near constant pan-European warfare.

At 1.3 billion livres, one could say it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Precision is impossible, but the French debt might have been as great as 12 billion livres by the time of the calling of the Estates General in 1789. But the financial costs of its involvement in the American Revolution are always cited among the causes of the French Revolution—involvement that would have been out of the question had it not been for the first partition of Poland.

Further Reading:

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Paul Kennedy (New York, NY: Random House, 1987)

The War of the Spanish Succession, James Falkner (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 2015)

The War of the Austrian Succession, Reed Browning (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993)

The Seven Years War in Europe, Franz A.J. Szabo (Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman, 2008)

America’s First Ally, Norman Desmarais (Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2019)

One thought on “From the First Partition of Poland to Yorktown”

This essay is very illuminating from a point of view not normally seen. However, France had three principal aims in entering the American War, all involving ripping off territory controlled by the British while the British were tied down in North America: 1) as much of India as they could get (and Suffren’s expedition to do that almost succeeded); 2) Barbados (which was impossible to reach due to weather at the moment the French tried); 3) Jamaica (Rodney’s crushing victory at the Battle of the Saintes ended that effort). So, if France had been able to capture those places, she could have avoided or at least delayed the bankruptcy that caused the French Revolution in 1789.