On October 18, 1777, New York provincial assemblyman, and tory, Crean Brush, penned his final will and testament from prison in Boston. After nineteen months of incarceration which included being held in irons, and “in a state of body and mind so debilitated by misfortune,” Brush made provisions for his wife Margaret, stepdaughter Frances, and biological daughter in Ireland, Elizabeth.[1]

American rebels captured Brush during the British evacuation of Boston in March 1776. Destined for Nova Scotia, Brush and his cargo of confiscated linens and silks were on a ship captured by privateers off Cape Ann. Three weeks after writing his will, Brush turned the tables on his captors and escaped. His daughter Elizabeth wrote that with “the assistance of a faithful friend he effected his escape . . . in the disguise of an Indian.”[2] An early American biographer tells it differently:

On Wednesday, the 5th of November following, Mrs. Brush, as was her custom, visited her husband in his cell, and remained with him several hours. The time for locking up the prisoners for the night having come, she was requested to terminate her visit. As the turnkey stood at the door, waiting for her appearance, a tall figure in woman’s garb passed out of the cell, walked with deliberation to the outer door, and disappeared in the darkness . . . Mr. Brush had escaped in his wife’s clothing.[3]

Having slipped past the jail guards, Brush managed a journey from Boston to British-controlled New York City, his first home in America after immigrating from the Kingdom of Ireland in 1762.[4]

Crean Brush was born in Northern Ireland to landed gentry in Tyrone County around 1725. By the 1760s he was a lawyer and widower with a daughter, Elizabeth. Leaving her in the care of his sister Rebecca and brother-in-law Arthur Clarke, Brush left a comfortable life for grand opportunities in North America.[5]

He practiced law in New York with Irish lawyer John Kelly and plied his craft on typical legal fare including deeds, powers of attorney and wills. Shortly after establishing himself in New York, Brush obtained employment as a law clerk in the office of Deputy Secretary Goldsboro Banyar.[6]

His personal life changed quickly. Brush courted Margaret Schoolcraft and they married in the Dutch Reformed Church. Margaret brought to the marriage her deceased sister’s illegitimate daughter Frances Montressor, being raised by Margaret as her daughter.[7]

Gov. William Tryon said Brush “conducted himself with diligence and integrity” while working for Banyar. It was in this capacity that Brush installed himself into the patronage machine of New York. Banyar, like Brush, was a lawyer born in the British Isles, the former in London, long-tenured with three decades in provincial government, with “a hand in virtually every land transaction . . . building valuable relationships and a considerable fortune.”[8] Brush grew to consider Banyar a close friend.

In 1772, Brush moved his family 200 miles northeast of New York City to the village of Westminster. Located on the Connecticut River, Westminster was the seat of government for newly-formed Cumberland County with its 4,024 people and 774 heads of families.[9] Brush brought his habit for ostentatious dress, and purchased a home in Westminster “north of the meeting-house, and was the only building in the town whose four sides faced the cardinal points.” The move was accomplished during legislative action establishing governance in the county—Brush was groomed and poised to be a major player.[10]

His connections paid-off—he was chosen commissioner of the court, county clerk, and surrogate of the court. As surrogate, he represented the colonial secretary and held power to administer oaths and oversee probate matters. Brush was involved in Cumberland’s division of townships into districts, and a circular bearing his name summarizing the changes was posted throughout the county.[11]

Toward the end of his first year in Westminster, a petition from freeholders in Cumberland County called for representation in New York’s general assembly. They elected Crean Brush and Samuel Wells of Brattleboro asassemblymen.[12]

Brush and Wells arrived in New York City in January 1773, and Brush was admitted to the assembly on the afternoon of February 2. The very next day he presented a spate of business related to Cumberland County, proposing amendments to existing legislation regulating highways, inns and taverns, and “a bill for raising the sum of £250, in the county of Cumberland, towards finishing the courthouse and gaol already erected in the said county.”[13]

Cumberland, Charlotte, and Gloucester Counties were recent creations from Albany County. Albany consisted of territory between the Hudson River and Lake Champlain in the west, and the Connecticut River to the east. The Green Mountains bisected the region and settlement accelerated after Britain’s victory in the French and Indian War. New York’s claim was supported by a 1684 grant from King James to his brother the Duke of York. In 1764, the Crown elicited delight from New York by confirming the Connecticut River boundary.[14]

The New Hampshire government had also been issuing land warrants in the same region. An impressive 138 chartered townships had been created on the west side of the Connecticut River which were divided and sub-divided, changing hands, in many cases trimmed to sizes sufficient for single-family sustenance farming. A chaotic tangle of competing land ownership between “Yorkers” and “New Hampshire Grant” holders pervaded the mountains, fields and forests, resulting in distrust and violence.[15]

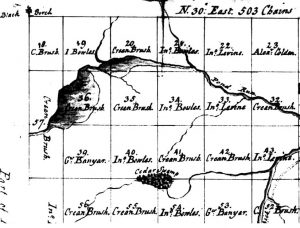

The New York and New Hampshire governors executed their grants differently but were equally motivated by fees augmenting their salaries. A patent—a survey and organization of unsettled land—was an asset for speculative gain or tenant income. Land ownership was power, and those with authority over it werefodder for bribes and for rewarding allies, friends and relatives. The beneficiaries of patents were groups called “proprietors” who were obligated to pay Crown taxes called “quit rents.” Crean Brush was a proprietor in several New York patents and owned well over 30,000 acres in Charlotte, Cumberland, and Gloucester counties.[16]

Between April 1765 and June 1776, over 2,000,000 patented acres were granted by New York governors in the New Hampshire Grant region. New Hampshire governor John Wentworth issued 3,000,000 acres west of the Connecticut River and to himself 65,000 acres. Both colonies issued grants to land speculators, though Wentworth was willing to grant land to any group willing to pay his cheap fees, allowing speculators to make a profit while offering affordable prices. Yeoman farmers poured in from New England, while New York patents were largely granted to New York City lawyers, merchants and speculators.[17]

In 1765, New York ruled the New Hampshire Grants illegal, requiring their owners to pay half-fees to validate claims that didn’t overlap with a New York patent. In response, a petition representing 600 New Hampshire Grant holders seeking a redress of grievances reached the Crown. A King in Council ruled that New York could no longer patent land in the New Hampshire Grant region. In April 1767 the governor of New York received tersely worded instructions: “His Majesty Commands you make no grants of these Lands and that you do not molest any person in the quiet possession of [Wentworth’s] Grant, who can produce good and valid Deeds.”[18]

The Crown rebuked New York’s land practices, issuing an acreage limit. Governor Tryon argued against the ceiling, explaining that large grants to “Gentleman of weight and consideration” were a bulwark against “the general levelling spirit” in the colonies. Compliance with the 1767 temporary ban on patents in the New Hampshire Grant region was largely ignored.[19]

In the provincial assembly, Crean Brush offered his legal writing skills to help establish New York dominance of the Green Mountain region. Brush barely warmed his seat in the assembly when he joined Philip Schuyler to draft a definitive document enumerating New York’s claim to the Connecticut River boundary. Intended for the colony’s agent Edmund Burke, the copious and detailed document was called A State of the Right of the Colony of New-York, with respect to its eastern boundary on Connecticut River, so far as concerns the late encroachments under the government of New-Hampshire. The piece was read before the assembly on March 8, 1773 and subsequently sent to London.

In March 1774 Brush was serving on the assembly’s committee of grievances when it received a petition from a subject in Charlotte County “complaining of many Acts of Outrage and Cruelty, and Oppression committed against their Persons and Properties by the Bennington Mob, and the Dangers and Injuries to which they are daily exposed.” The petition asked the Assembly to “take them under their Protection, and secure them against future Violence.”

The yeoman farmers of the New Hampshire Grants made common cause with speculators to protect their homes and property. New York surveyors caught on New Hampshire Grant properties were driven off by their owners and neighbors. Ethan Allen, owner of a New Hampshire Grant investment enterprise called the Onion River Land Company, led the Green Mountain Boys in an information and armed resistance effort against New York. Allen and his men were labeled insurgents by the committee of grievances. The “Bennington Mob” was accused of throwing the region into turmoil through acts of property destruction, intimidation, and violence. Brush co-drafted the infamous bill known as the “12 Bloody Acts,” which made riotous assemblies of three or more individuals a felony, made any sheriff or magistrate killing a rioter in the act of apprehending free of penalty, and called for the arrest of Allen and other leaders of the Green Mountain Boys.[20]

In May, Ethan Allen sent Brush and Wells a warning with a postscript for the Irishman:

I have sundry ways received intelligence of your hatred and malice toward the N. Hampshire Settlers on the west side of the Green Mountains and particularly towards me. The report you made on behalf of Mr. Clinton is noticed by the Green M Boys. They have also took a retrospective view of a number of learned attorneys and gentleman (by birth) interested in the lands (by N. York Title) on which they dwell deluding the Assembly Part of the Members . . . I know it was the Land Schemers [who] Influenced the Assembly to pass the 12 Bloody Acts . . . Wells and You are but busie Understrappers to a Number of more Overgrown Villains which can Murther by Law without remorse. But I have to inform that the Green Mountain Boys will not tamely resign their necks to the halter to be hanged by your cursed fraternity of land jockeys who would better adorn a halter than we, therefore as you regard your own lives be careful not to invade ours for what measure you meet it shall be measured against you . . .

P.S. Mr. Brush Sir

As a testimony of gratitude for the many unmerited kindnesses, and services, you have done us the last session at New York &c &c we intend shortly visiting your abode, where we hope to have the honor of presenting you the beech seal . . .

To be yours sincerely,

Green Mountain Boys[21]

In addition to fighting the Bennington Mob, the conservatives in New York’s government were grappling with colonial resistance efforts promulgated by the First Continental Congress. Cadwalader Colden told the assembly at the start of the 1775 session: “We cannot sufficiently lament the present disordered state of the colonies . . . If your constituents are discontented and apprehensive, examine their complaints with calmness and deliberation.”[22]

Whigs in Brush’s constituency networked to undermine Royal authority and Congress was the catalyst. Meetings of patriots representing townships across Cumberland met in Westminster at various times from Fall 1775 through Winter 1776, forming a Cumberland Committee of Correspondence and encouraging support for the resolutions of Congress.[23]

On February 17, 1775, Suffolk County assemblyman Nathaniel Woodhull made a motion “that thanks of this house be given” to representatives of Congress “for their faithful and judicious discharge of the trust reposed in them by the good people of this colony.”[24] Woodhull’s motion was debated and voted down; Brush and Wells voted against it. The same scenario played out a few days later when assemblyman and congressional delegate Philip Livingston proposed a formal thanks to the colony’s merchants and citizens for their “public spirited, and patriotic” conduct in carrying out Congress’s non-importation association. Once again, Brush and Wells voted in the negative.

On February 23, Brush seized an opportunity for going on the record opposing Congress. A motion was made by a Livingston ally for appointment of delegates to the next Congress in Philadelphia on May 10.[25] Brush articulated his belief that a proper avenue for the colony’s redress of grievances existed within the established framework:

I again freely repeat my opinion . . . As the proposed Congress is to be a continuation of the last, and is to meet in consequence of their vote declaring the necessity of holding it, by nominating Delegates for it we shall, in effect, recognize the last Congress, and make ourselves, parties to all the measures then agreed upon. If this will be the consequence, as I conceive it clearly will, of the present motion, no other reason can be necessary why this House should not agree to it; because we have already determined not to consider the Proceedings of that Congress, much less espouse its principles or adopt its measures. But, sir, we are the legal and constitutional Representatives of the people; to us the care of their liberties is, in the most sacred manner, entrusted; and I think it would be a breach of our trust to delegate that most important charge to any body of men, whose powers are circumscribed by no law . . . I hope this House will have too much prudence, as well as virtue, to give a sanction to an assembly who would sap our Constitution, and may probably involve this once happy country in all the horrors of a civil war. However, let their determination be as it will, I shall have the satisfaction of doing my duty, in declaring my dissent to the motion now before the House.[26]

Brush and others defeated the proposal 17-9.[27]

On March 13, 1775, Crean Brush was with the Assembly when armed conflict exploded at Westminster. An armed mob of eighty persons occupied the courthouse to prevent the next day’s business. The anger stemmed from eviction and foreclosure actions scheduled at the courthouse. Sheriff William Paterson of Cumberland County arrived with a posse and, failing to disperse the mob peacefully, fired warning shots. The mob returned fire, wounding a judge. In subsequent fighting one rioter was killed and nine wounded. The court defiantly held business the next day, and “a number of persons partly of the said County (Cumberland) and partly from the Provinces of Massachusetts Bay and New Hampshire assembled, surrounded the Court House.” The judges and clerks were imprisoned in the county jail.[28]

“The Westminster Massacre” caused Lieutenant Governor Colden to excoriate the assembly to “strengthen the hands of civil authority” and warn that “negligence of government will ever produce a contempt of authority.” The assembly debated whether to provide support for re-establishment of peace in Cumberland County. The measure passed on a faction-line vote with Brush in the affirmative. Brush made a motion for funds to supplement the effort, which also passed.

Open war after the Battles of Lexington and Concord made Brush’s residence in Westminster untenable. Added to his corrupt “Yorker” status was a perception that Brush was an unrepentant Tory. Not only did he oppose Congress vehemently, in October 1774 Brush had called for the arrest of Dummerstown farmer Leonard Spaulding for high treason after he spoke out against the British Quebec Act which legitimized Catholicism in Canada. Outrage led to Spaulding’s release and left simmering anger toward Brush and the county magistrates.[29]

Crean Brush, with “utmost difficulty and hazard of his life,” fled with his wife to Boston.” His property in and around Westminster was confiscated. His personal library, law books and furniture were “scattered among the households of the neighborhood.” Brush’s co-representative, Samuel Wells, had deeper roots in his community and tried to remain in Brattleboro, enduring harassment from an aggrieved Leonard Spaulding. Unable to stay an uninterested party, Wells became a spy for the British. He was found out and fled, dying in Canada after the war. Among Wells’ creditors at the time of his death was the Estate of Crean Brush.[30]

Brush did not sit idle within British lines at Boston. He approached commander-in-chief Gen. Thomas Gage for employment. In October 1775 Gage told Brush that “the inhabitants have expressed some fears concerning the safety of goods especially as a great part of the houses will necessarily be occupied by His Majesty’s Troops and the followers of the Army as Barracks during the winter season.” Gage offered Brush a wage to collect and catalogue personal property of loyal Bostonians leaving the city.[31]

On January 10, 1776 Brush requested permission to conquer the New Hampshire Grant region, proposing:

one body under his command to occupy proper posts on the Connecticut River, and open a line of communication from whence westward towards Lake Champlain . . . your memorialist’s intimate knowledge of that frontier enables him to ensure your excellency that such an establishment in that country will become absolutely necessary for the purpose of reducing to obedience, and bringing to justice, a dangerous gang of lawless banditti, who, without the least pretext of title, have by violence, pressed themselves of a large tract of interior territory, between the Connecticut River on the East, and the waters of the Hudson’s River and Lake Champlain on the West, in open defiance of government.[32]

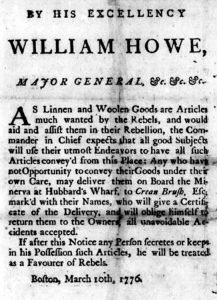

Nothing came of this request, but Gen. James Robertson recommended Brush to Gage’s replacement, Gen. William Howe. Howe considered Brush a “Loyal & Zealous Subject,” and employed him in work that earned the loyalist animosity in Boston.[33] With evacuation in the near future, Howe posted a circular throughout the town:

As Linen and Woolen Goods are Articles much wanted by the Rebels, and would aid and assist them in their Rebellion, the Commander-in-Chief that all good Subjects will use their utmost Endeavors to all such Articles convey’d from this Place; Any who have not Opportunity to convey their Goods under their own Care, may deliver them on Board the Minerva at Hubbard’s Wharf, to Crean Brush, Esq; mark’d with their Names, who will give a Certificate of the Delivery, and will oblige himself to return them to the Owners, all unavoidable Accidents accepted.

If after this Notice and Person secrets or keeps in his Possession such Articles, he will be treated as a Favourer of the Rebels.[34]

Brush was empowered to question merchants and search their property upon suspicion of non-compliance. He realized help was needed and appealed to General Robertson. Brush was assigned four loyalists including Richard Hill, a native of Ireland and loyalist volunteer who had lived on 900 acres in Westminster purchased from Brush. Hill was a member of Sheriff Paterson’s posse that engaged rioters in the Westminster Massacre. Consequently, Hill’s home was plundered by the mob, and he fled to Boston with his family.[35]

A day after Howe’s proclamation, merchant Samuel Dashwood was at his home and shop when a sword-wielding Crean Brush forced his way through the back door. Dashwood and his family watched the unwelcome visitor brazenly move through the home to the front. Brush opened the door to the shop, allowing his posse to enter. The raid lasted two hours, and according to Dashwood was served “with great force and violence” and “terror of myself and family.” Dashwood also claimed Brush threatened that “if any person should presume to interrupt . . . they would thrust their bayonets into such a person.” Nine large trunks and two large chests of silks and cloth were carried away.[36]

Merchant John Rowe recorded the visit Brush paid:

This morning I rose early and very luckily went to my warehouse—when I came there, I found Mr. Crean Brush with an order and party from the Gen. who was just going to break open the Warehouse which I prevented . . . They took from me to the Value of Twenty Two hundred & Sixty Pounds Sterling . . . in Linens, Checks & Woolens. This Party behaved very Insolently and with Great Rapacity.[37]

Brush carried out similar confiscations on merchants Samuel Austin, Cyrus Baldwin, John Barrett, Samuel Partridge, and John Scollay. Austin wrote that Brush “did by force and Arms, with near Twenty Soldiers, with their Guns and Bayonets enter my House and took from me in goods and merchandise. I apprehend it needless to say anything about the rude and insulting behavior of the officer (Crean Brush) who took my goods.” Brush’s confiscations surely brought him a measure of satisfaction—Austin, Baldwin, Barrett, Dashwood, Partridge, and Scollay were Sons of Liberty.[38]

Brush was determined to head off complaints of his raids, explaining to General Robertson:

These People your Memorialist are irritated against him but your Memorialist begs leave to assure your Honor he is fully able to prove that his Conduct toward them was governed with politeness coolness & moderation true it is that when attempts were made to engage his attention in tedious dissertations on Magna Charta & the rights of British Subjects with intent to retard him in the execution of his Office he did interrupt such Harangues & with an Irony which inflamed their resentments complimented them on their Eloquence which had in Town Meetings been so successful as to throw all America into confusion but that I was upon Business which I was determined to execute without interruption.[39]

With only a week to complete his assignment, Brush worked on little sleep and faced a scarcity of transportation: “The goods I received from the stores taken on board and stowed away with all the care and attention my peculiar situation would possibly admit.” He chose the ship Elizabeth and “had but two boys and a man onboard none of them mariners and ignorant of stowing goods which were however put away the best manner they could.”

Elizabeth departed Nantasket Roads at the entrance of Boston Harbor on the afternoon of March 21, 1776, carrying sixty-three passengers including thirteen soldiers and four enslaved people.[40] The voyage of Capt. John Ramsey’s ship was tension filled. In addition to seized materials in trunks and cases, Brush had on board the four loyalists that helped him along with their families, in cramped quarters between decks guarding their own provisions.[41]

A British major added to Brush’s burden by placing nineteen barrels of flour in his care. The crew broke into one of the barrels and Brush harangued them. He was resting below decks when an angry crew member, taking umbrage, threatened him. Brush and the crew sparred verbally, causing Captain Ramsey to lose patience and promise him imprisonment if he “uttered three words more.”[42]

On March 29, Elizabeth became separated from its escort and was fallen upon by the Yankee privateer Hancock fifty miles east of Cape Ann. Hancock closed with Elizabeth and fired a broadside. Elizabeth answered with small arms fire. Two more privateers arrived, convincing Captain Ramsey to surrender in the late afternoon.[43]

Elizabeth was brought into Portsmouth. Brush’s inventories, orders and sealed letters were confiscated. General Washington was informed that the most valuable part of the prize taken off Cape Ann was an ample store of rum from the West Indies, and the prisoners “were examined by the General Court, who were all committed to prison Yesterday, Brush in Irons.”[44]

Brush, uniquely singled out for irons, was compelled to provide sworn affidavits related his frantic days carting off cloth and silks. His confiscations were not considered in light of the military purpose in his order from General Howe, but rather as wanton theft. The exhausted lawyer must have thought it possible he would never leave the jail alive. He penned his will, reaffirming for posterity his loyalty to the Crown by dating the document “the 18th year of his Majesty’s Reign.” His estate was divided between his wife Margaret, stepdaughter Frances, and natural daughter Elizabeth. The bequeathment consisted of debts he was owed but was principally tied up in his vast landholdings.[45]

Brush escaped but died in New York City just months later. The May 21, 1776, edition of The Independent Chronicle and the Universal Advertiser of Boston reported that Brush “retired to his chamber, where, with a pistol, he besmeared the room with his brains.”[46]

Brush’s daughter in Ireland applied to the Loyalist Claims Commission for relief. The certificates supporting Elizabeth’s application avoided specific mention of how he died. General Robertson stated that “his endeavors drew on him the resentment of all who wished for Rebellion & Revolt,” and that “his life was rendered miserable, and his death occasioned by misfortune.”[47]

In the first half of the nineteenth century, a legend persisted that Brush cut his own throat with a razor in a New York law office.[48] Cumberland County Loyalist Timothy Lovell, in sworn testimony in a lawsuit brought by Brush’s Estate for the recovery of debts, said he was fetching firewood for Brush at his residence-in-exile in New York City when he returned to find him dead with his throat cut.

Historians Patrick J. Duffy and Nicholas Muller speculate that Ethan Allen murdered Brush. In 1777 Allen, who bitterly detested loyalists and especially Brush, was a prisoner of war on parole and free to walk the New York city streets until the British sent him to Long Island. Allen broke his parole in August, was brought back to the city and imprisoned in the provost. It is possible that Allen ran into Brush or was told his whereabouts. Brush died while Allen was in the provost, but Duffy and Muller, citing the frequency of escapes from that provost, believe Allen may have slipped out, killed Brush and returned.

The strangest twist in Brush’s story was his stepdaughter Frances’s marriage to Ethan Allen. In February 1784 Frances, at twenty-four a widow with a young child, and widower Allen at forty-six, married in Westminster. This effectively made Allen a co-beneficiary to Brush’s estate.[49]

Brush’s wife Margaret remarried and lived the rest of her life in Westminster. In the wake of her father’s death, Elizabeth Brush applied to the Loyalist Claims Commission for financial assistance, obtaining supporting certificates from Gage, Howe, Robertson, and Tryon.

In 1782 she married Thomas Norman of Drogheda, near Dublin. Norman used his modest inheritance to purchase a commission in the British Army and was financially ruined by a lawsuit. As a result, he vigorously assisted in recovering his late father-in-law’s estate.[50] Elizabeth owned one-third of her father’s estate and purchased the other two-thirds from Margaret and Frances, becoming the sole heir. Attorneys including Brush’s friends John Kelly and Goldsboro Banyar tried to recover Crean Brush’s debts and land. Some land in New York proper was recoverable, but the land in Vermont was “irrevocably lost” to confiscation. The Normans, along with other claimants, recovered a cash settlement from Vermont.

Elizabeth and Thomas Norman had four children and moved to the United States, first living in Westminster, then permanently settling in Caldwell, New York, on land owned by Brush.[51]

[1]The Will of Crean Brush, New Hampshire, Probate Court (Cheshire County); Probate Place: Cheshire, New Hampshire, case 101, vol. 1-2, 1771-1793.

[2]Elizabeth Martha Brush to the Earl of Carlisle, November 19, 1782, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, Kew, Surrey, The National Archives of the United Kingdom (TNA).

[3]Benjamin H. Hall, History of Eastern Vermont, from its earliest settlement to the close of the eighteenth century (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1858), 624.

[4]Elizabeth Brush to the Earl of Carlisle, American Loyalist Claims Commission, TNA; Evidence of the foregoing Memorial of Thomas Norman and Elizabeth Martha his Wife Daughter of Crean Brush, January 19, 1788, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO12/30, TNA.

[5]John J. Duffy and Eugene A. Coyle, “Crean Brush vs. Ethan Allen: A Winner’s Tale,” Vermont History, Vol. 70, Summer/Fall (2002), 104; Certificate of Arthur Clarke, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA.

[6]Duffy and Coyle, Winner’s Tale, 104; Crean Brush Account Books, 1765-1766, New York Historical Society, https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A106621; Certificate of Lord William Tryon, February 10, 1784, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA.

[7]The Archives of the Reformed Church in America, New Brunswick, New Jersey, Collegiate Church, Ecclesiastical Records, Baptisms, Members, Marriages, 1639-1774;John J. Duffy and Eugene A. Coyle, “Crean Brush vs. Ethan Allen: A Winner’s Tale,” Vermont History, Vol. 70, Summer/Fall (2002), 104.

[8]Certificate of Lord William Tryon, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA; Biographical Note, Goldsboro Banyar and Banyar Family Papers 1727-1904, New-York Historical Society Museum & Library, http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/nyhs/banyar/bioghist.html.

[9]An Inventory of Lands belonging to the Estate of the late Crean Brush of Cumberland County, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/116, TNA; Jay Mack Holbrook, Vermont Census of 1771(Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Center, 1982), Table 9, Cumberland County Population in 1771 and 1791.

[10]Hall, Eastern Vermont, 604-605; Session] Begun the 7th of January, 1772, and ended, by prorogation, the 24th of March Following, Journal of the Votes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Colony of New York, from 1766 to 1776, inclusive (New York: J. Buel, 1820), 64, 70, 110 (JVGA).

[11]Hall, Eastern Vermont, Appendix G—Division of Cumberland County into Districts, 743-744.

[12][Session] Begun the 5th of January, 1773, and ended, by prorogation, the 8th of March Following, 41, JVGA, 41; Hall, Eastern Vermont, Cumberland County Civil List: 767.

[13][Session] Begun the 5th of January, 1773, JVGA, 42-44, 65.

[14]Holbrook, Vermont Census, Table 3, Origin of Vermont Counties; Representation of the Lords of Trade on the New Hampshire Grants, December 3, 1772, in E.B. O’Callaghan ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of New York (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1857), 8:330-337 (DRCNY).

[15]Charles A. Jellison, Ethan Allen: Frontier Rebel (Syracuse: University of Syracuse), 19-21.

[16]Irving Mark, Agrarian Conflicts in Colonial New York: 1711-1775, (New York: Ira J. Friedman, Inc., 1965), 19; An Inventory of Lands belonging to the Estate of the late Crean Brush, TNA; Hall, Eastern Vermont, 605.

[17]Jellison, Frontier Rebel, 20, 22; Mark, Agrarian Conflicts, 22.

[18]Jellison, Frontier Rebel, 23-24; Earl of Shelburne to Governor Moore, April 11, 1767, DRCNY, 8:917.

[19]Mark, Agrarian Conflicts, 25, 31; Governor Tryon to the Earl of Hillsborough, April 11, 1772, DRCNY, 8:293-294; Frederick Franklyn Van de Water, Vermont: The Reluctant Republic, 1724-1791 (New York: The John Day Company, 1941), 56.

[20]Mark, Agrarian Conflicts,196; Jellison, Frontier Rebel, 44-45, Hartford Courant, June 21, 1774; An Act for preventing tumultuous and riotous Assemblies, March 9, 1774, in William Slade, ed., Vermont State Papers (Middlebury: J. W. Copeland, 1823), 42-48.

[21]Ethan Allen to Crean Brush and Samuel Wells, May 19, 1774, in John J. Duffy, ed., Ethan Allen and His Kin: Correspondence, 1772-1819 (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1998), 16-17.

[22][Session] Begun the 10th of January, 1775, and ended, by prorogation, the 3rd of April Following, JVGA, 4, 85, 100.

[23]The Pingrey Papers, History of Windsor County Vermont, ed., Lewis Cass Aldrich and Frank R. Holmes (Syracuse: D. Mason and Co., 1891), 47-49 (HWCV).

[24][Session] Begun the 10th of January, 1775, JVGA, 38.

[25][Session] Begun the 10th of January, 1775, JVGA, 40, 44-45.

[26]Speech of Mr. Brush, of Cumberland County, on this question, February 23, 1775, Peter Force, American Archives, Northern Illinois Digital Library, https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A98782.

[27][Session] Begun the 10th of January, 1775, JVGA, 44-45.

[28]Hall, History of Eastern Vermont, 184-186; Jellison, Frontier Rebel, 98-99; Colonel Wells and Crean Brush, representatives of Cumberland County report of a violent riot in their county during which Justice Butterfield was wounded, New York Colony Council Minutes, March 21, 1775, NYSA_A1895-78_V026_06, New York State Archives, https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/85117.

[29]The Pingrey Papers, HWCV, 49-50.

[30]The Memorial of Thomas Norman and Elizabeth Martha Brush, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA; Hall, Eastern Vermont, 628, 724-725.

[31]Thomas Gage to Elizabeth Martha Norman, December 5, 1783. American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA; Thomas Gage to Crean Brush, October 1, 1775, in William B. Clark et al., eds. Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 13 volumes (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1964-2019), 2:263-264 (NDAR).

[32]Hall, Eastern Vermont,611-612.

[33]William Howe to Elizabeth Martha Norman, December 13, 1783, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA.

[34]Proclamation from Gen. William Howe to the People of Boston, March 10, 1776. Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, Roll 88, Record Group 360, NARA.

[35]Certificate of William Paterson, Sherriff of Cumberland County for Richard Hill, March 18, 1780,American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/13, TNA; The Claim of Richard Hill, Esq., a loyalist from the Township of Westminster, County of Cumberland,American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/13, TNA; Crean Brush to William Howe, March 26, 1776, NDAR, 4:522-523; Hall, Eastern Vermont, 611-612.

[36]Samuel Dashwood Deposition on goods seized by British troops. Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, Roll 88, Record Group 360, NARA.

[37]John Rowe, Letters and Diary of John Rowe: Boston Merchant 1759-1762 1764-1779, ed. Annie Rowe Cunningham (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1903), 301-302.

[38]Samuel Austin to John Adams, December 23, 1785, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-18-02-0032; Col. William Palfrey, An Alphabetical List of the Sons of Liberty who din’d at Liberty Tree, Dorchester, August 14, 1769, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, http://masshist.org/database/8.

[39]Crean Brush to James Robertson, March 25, 1776, NDAR, 4:501-502.

[40]Joshua Wentworth to Stephen Moylan, April 15, 1776, NDAR, 4:828-830.

[43]Extract of Letter from Cambridge dated April 7, 1776, NDAR, 4:694; Journal of the Continental Congress, October 14, 1776, NDAR, 6:1263-1265.

[44]John Gizzard Frazer to George Washington, April 14, 1776, NDAR, 4:808.

[45]Isaac Smith, Sr. to John Adams, April 6, 1776, NDAR, 4:676; Will of Crean Brush.

[46]Hall, Eastern Vermont, 626.

[47]James Robertson to Elizabeth Brush, February 1, 1784, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA.

[48]Hall, Eastern Vermont, 625.

[49]Duffy and Muller, Inventing Ethan Allen, 129-133, 142-146.

[50]Henry Dogherty to the Loyalist Claims Commission, February 10, 1784, American Loyalist Claims Commission, 1776-1835, AO13/63, TNA.

One thought on “Hell’s Half-Acre: The Fall of Loyalist Crean Brush”

Samuel Wells did not die in Canada after the war. He died in Brattleboro on August 6, 1786 and was buried there, in the Meeting House Hill Cemetery.

Sources:

1. Vermont, U.S., Vital Records, 1720-1908.

2. Hall, Benjamin H., History of Eastern Vermont, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1858, p. 725.

3. Burnham, Henry, Brattleboro, Windham County, Vermont: Early history with biographical sketches of some of its citizens, Brattleboro: D. Leonard, 1880, p. 64.

His surviving family settled in Canada between 1798 and 1802, in what is now Farnham, Quebec.

He is my fifth great grandfather.