During the era of the American Revolution, French and Spanish regiments were comprised primarily of Roman Catholics who customarily have objects and implements blessed before their use to invoke God’s blessing, favor and protection on them. Small objects, like medals, are blessed with a simple prayer. Larger, more important objects and occasions are blessed in the context of a Mass, the major liturgical ceremony. These include sacraments (baptism,[1] first communion, confirmation, marriage, and ordinations of priests and bishops) and larger objects and implements (houses, vehicles, vessels and ships, and regimental flags).

Accounts of the blessing of flags are extremely rare which makes the translation of the following document about the blessing of navy flags so important. But, to properly understand it, we should explain how the Mass was celebrated in the eighteenth century. From the Council of Trent (1545–1563) to the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), the altar was against a wall, and the priest and the congregation faced the same direction. In other words, the priest had his back to the congregation.

The Mass was entirely in Latin. It began with some prayers of repentance followed by one or two readings from the Bible and a reading from the Gospels. These were called lessons and were often followed by a homily or sermon in the native language explaining the readings and applying them to daily life. The first readings were read on the right side of the altar. The lectionary was then transferred to the left side for the reading of the gospel. Some churches had ambos or pulpits forward of the altar.

The main portion of the Mass begins after the readings and consists of three parts: the offertory, consecration and communion. The offertory involves the bringing of the bread and wine to the priest who then prays over it and blesses it. The consecration invokes the presence of God, the saints and the entire church. The priest then consecrates the bread and wine which Catholics believe now becomes the body and blood of Christ. He then leads the congregation in several more prayers before distributing the bread and wine (today usually only the bread) to the congregation at communion. The Mass ends with a few final prayers and the blessing of the people.

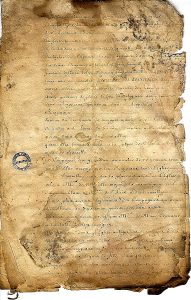

The original document describing the blessing of these navy flags is in the Archives de Finistère. It is in poor condition with tears, stains and blotches. It most likely dates from 1778 when the warship l’Actionnaire entered the service of the French Navy. Her captain, Vincent-Joseph-Marie de Proisy de Brison,[2] was prominently involved in the ceremony of the blessing of the flags; he died the following year. Here is a translation of what we can understand:

Regarding what has happened at the blessing of the navy flags [blotch] in the church of St. Louis at Brest.[3]

The celebration was announced the previous day by a carillon of bells and the following morning we beat the general[4] all along the gathering on Cazance Cross square. Army captain [torn] the flags which were to be blessed. It was decorated with gold fleur de lis and a tun in the middle of each with these words “per mare et terra”[5] and others had a white cross [1 word unintelligible] of red [2 words illegible] decorated with gold fleur de lis. There were also old flags that were captured [?] at the expedition of Riogavaiu [?]

About 10 [1 word unintelligible] of troops marched by division to St. Louis. The general was beaten [4 words unintelligible] in the [1 word unintelligible] of the battalion.

When they arrived at St. Louis square, they [torn] level of battle.

The company of grenadiers numbering 70 men, all elite men, accompanied the flags into church and the regiment remained on the square aside of the church. Then Mr. de Villevielle,[6] major of the Marines, took the white flag to Misters de St. Prix[7] and de Nouailles[8] as the most senior captains of the companies which are actually at [1 1/2 lines unintelligible] carried by Mr. Moré[9] to where Mr. de la Salle Proisy indicated.

The [1 word illegible] in church to the sound of fifes and drums in this order: fifes, drums, flags [1 1/2 lines unintelligible] two lines of file [1 1/2 line unintelligible]. Those who carried the flags arrived in the sanctuary [1 1/2 line illegible] . . . of the gospel and those who carried the old [flags] placed themselves [1 line unintelligible] except the tone of the exhortation when six grenadiers made them file to the edge of the sanctuary and they doubled back to the choir entrance all of which were guarded. The epistle side was reserved for the men of [1 word unintelligible] and that of the gospel for the men of the Navy. The company was brilliant and very numerous in church [1 word unintelligible] The women arrived there early.

The clergy proceeded to the choir to the sound of the march of the troops. All the preachers [1 word] Mr. the Rector officiated with deacon and subdeacon. Father [one word illegible] was his assistant. Msgr. the bishop de l’Eon[10] was supposed to preside over the ceremony, but he was incapacitated. He designated Mr. the Rector. The ceremony began with the psalm Exaudi di [Hear us, Oh God], which, like the rest of the office, was sung by two choirs and the organ [?] of the symphony. The Mass of the Holy Spirit followed when the troops then [unintelligible.]

After the secret,[11] an armchair was placed in the middle of the altar where the celebrant was seated turned toward the people. All the clergy were lined up farther away toward the sanctuary. Mr. Abbé du Maimaw uttered the following speech:

Blessed be the Lord, the God of the armies who strengthens those who fight and who teaches them to be victorious.

And so, many other times the prophet [one word], in the throes of a holy reconnaissance, has seen the benefits of the God of Israel who has vanquished all the enemies as well. Thus, sirs, it is often up to you to express yourselves as [one word] because the same God has made you feel a wall. Realize what his strong arm can do in favor of a nation which is dear to him here. Sirs, am I not permitted to proclaim an innumerable multitude of victories his valor has granted over the enemies of the state ruminating from glowing witnesses of divine protection, worthy subjects of the great prizes of the worlds? You bore the terror of his name to the farthest climes, devoted by the states of the service of his navies but even more devoted by the heart to his person and to his glory. It was very little for you, sirs, to humble, by a thousand defeats, the pride of the powers which dare to contest the empire of the seas. It required even more prodigious exploits that were foreign to your illustrious corps [and] would conclude by signaling your zeal.

Little accustomed to fighting on land but accustomed to winning, you have won as many times as you have fought. We have seen laurels growing everywhere under your feet in the defense of Camarec,[12] the sieges of Nice, Gibraltar and Barcelona, the glorious campaigns of Flanders and Italy, the captures of Cartagena and Rio di Janeiro are no less the praise of your value than the battles of the English Channel, Malaga and of so many other great naval actions which history alone has the right to count the number and to report the glorious circumstances.

Heroes by sea, heroes by land, it is by such exploits, sirs, that you have consecrated the motto which we see glowing on your flags. May Almighty God bless them with us to accompany you wherever you will bring them in his name for the glory of your august master. But you, Christian soldiers, manifest today such ardor to follow these heroes who lead you in combat. Remember that you should never abandon these flags, come what may, which will be granted to you as a sacred trust, but on the contrary you must animate yourselves one another in an emulation worthy of the French name to flee any action which answers to what we have the right to expect of you.

After that, may a wise minister, trustee of the King’s plans and of his graces, have authority to announce to him new efforts of your courage and crown them with new rewards. Especially, sirs, may you never lose sight of this other standard which is that of the religion of Jesus Christ which you profess in the most edifying manner of the world. Never forget that he is the true author of your triumphs. An exemplary piety has, up to now, merited us his omnipotent protection.

Continue to march under this same piety. The God of the armies will continue to combat with you and as you have always been victorious with him, you, sirs, will always become [in]vincible.

This discourse finished, the officers carried the flags [2 words unintelligible] to the deacons [1 word unintelligible] or seated [6 words unintelligible] which the celebrant did standing one against the other [?] [3 words unintelligible] to make [4 words unintelligible] who was seated after the [6 words unintelligible] presented it to Mr. de Villevielle after having had him put his hand on the gospel to give him [1 word illegible] the accolade. Misters de St. Prix and de Nouailles did the same.

These men then brought these flags to present them to the officers who carried the old ones to them [5 words unintelligible] captains of the army who brought them to the sacristy. The celebrant then sang the preface after which the troops knelt until the communion. The drums beat “to the fields,” at the time of the elevation, which interrupted a motet which had [3 words unintelligible] and the regiment which was in front of the church knelt. At this signal, we also beat “to the fields.” The Mass finished, the troops devoted themselves and one intoned the Te Deum[14] at the sanctus[15] to the devicto mortis aculeo[16] and, at the end, the “to the fields” was beaten.

During the Te Deum, the regiment that was outside the church fired two volleys. The Te Deum finished, the troops went out in the same order as they arrived except that Misters Mayor Coateasaun[?] and de la Salle Proisy carried the flags and a few other officers had retaken their place among the troops.

When the flags came into view of the troops who were outside the church, they fired a third volley at their appearance. They also went to join the others a little further which was cut off [1 line unintelligible]. At the end of the cold, the officers or soldiers presented their [1 word unintelligible], went to get the flags at Mr. the Count de L. . . [1 line unintelligible]. At the end of the ceremony, they withdrew the bayonet and brought the musket to the shoulder [3 words unintelligible]

[1 line unintelligible] Then, the infantry officers [9 words unintelligible] Mr. the Rector, Father Dumaine[?], some other priests and the commissioner or inspector of the troops went to Mr. de Villevielle’s avenue which was magnificently decorated. A room in the middle of which was a table made with a horse’s head with 70 or 72 covers where the order or profession both equally contributed to Mr. de Villevielle’s splendor or taste.

[1]Baptisms are generally performed as separate ceremonies today.

[2]Vincent-Joseph-Marie de Proisy de Brison (died Brest, July 28, 1779) a French Navy officer, captain of the 64-gun Actionnaire.

[3]The current church of St. Louis de Brest was reconstructed after World War II on the site of the original church built between 1686 and 1785.

[6]Philippe Charles François Pavée, Marquis de Villevieille (1738-1825).

[7]Probably Hector de Soubeyran de Saint-Prix (1756–1828) a French politician.

[8]Louis-Antoine, maréchal, duc de Noailles (1713-1793) captain (1770) then colonel (1774) of the Noailles regiment of dragoons.

[9]Probably Charles Albert de Moré de Pontgibaud (1758–1837) who was the Marquis de Lafayette’s aide-de-camp.

[10]Probably Jean François de La Marche, Bishop of Saint-Pol de Leon (1729–1806) in the Diocese of Quimper which was abolished and subsumed into a new diocese coterminous with the new “Departement de Finistère” during the French Revolution.

[11] The priest’s private prayer at the end of the Offertory of the Mass and before the Preface.

[13]In this sign you will conquer. The emperor Constantine supposedly saw a bright cross with this inscription emblazoned on it in the noonday sky, giving the assurance he needed to engage his rival Maxentius in battle at Rome’s Milvian Bridge in 312.

[14]The Te Deum is a lengthy hymn of praise with repetitious music.

[15]Holy, holy: a hymn, sometimes recited as a prayer, after the preface.

2 Comments

Great article. I was surprised at how religious the French troops were. I’d hope that the bread and wine “represented” the blood of Christ, and didn’t actually “become” it! On note 8, I believe it was likely General Louis-Marie d’Ayen de Noailles 1756-1804 who was Lafayette’s brother-in-law and commander of Noailles Regiment in which M. Dubuq (who was in Boston in 1775 -see my JAR article) also served.

Frederic – on the author’s deliberate choice of “becomes the body and blood of Christ,” he is referring to Catholic doctrine. Look up “transubstantiation” or see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transubstantiation.