Ned Streater (also spelled Streator) was a twenty-year-old man when he first served early in the American Revolution as a member of a Virginia Minute Battalion from Nansemond County during the Battle of Great Bridge in 1775. Streater served again during the Virginia campaign of 1780-81. What makes Ned Streater unique is not his multiple tours of militia service or the fact he received no written discharge to document his service to the Patriot cause, but that he was an enslaved African American. He is one of only three African American soldiers identified to date who fought on the Patriot side from the State of Virginia early in the war, at the Battle of Great Bridge.[1] The most notable African American Patriot to serve in Virginia’s first Revolutionary War battle, Great Bridge, was William (Billy) Flora, a free African-American from Portsmouth, Virginia.[2] Flora was reportedly one of the three sentries on duty at the south end of the Great Bridge on the morning of December 9, 1775, when the British assault took place. Flora’s story has been told many times and likely romanticized over the years.[3] Ned Streater’s story is quite different, and likely never previously told. His story provides insight into the military service of enslaved African American veterans and their post-revolutionary experiences.[4]

Today, Nansemond County, Virginia, is one of several extinct counties in the state. It was incorporated with the Independent City of Suffolk in 1972, and in accordance with Virginia law, when incorporated, the county ceased to exist.[5] Historical research into people and events in Nansemond County is difficult for other reasons beyond a name change. The county records were destroyed by fire on at least three separate occasions in 1734, 1779, and again in 1866.[6] This makes the content of Ned Streater’s pension application particularly valuable for the study of local history because it contains official court documents and proceedings, providing insight into his service and journey to freedom. Unlike many revolutionary veterans who moved west after the revolution, Ned remained in Nansemond County linked to his enslaved status. Ned Streater’s pension application was sworn and attested by Jeremiah Jones and Henry Lassiter in Nansemond County in 1833. He was successful in obtaining a pension in the amount of $112.55 that November but passed away only one month later at age seventy-eight. One is left to wonder if he actually received any of the pension funds he earned before his death.[7]

Ned Streater signed his pension statement with an X like many veterans, indicating he was illiterate, but clearly this was not any measure of his intellect. Ned was astute enough to file suit against his former enslavers in 1814 seeking his emancipation under existing Virginia law. His enslaver at the time of his revolutionary service was Willis Streater, for whom he served as a substitute in the militia. Willis Streater’s (Streator’s) estate documents date from 1802, but he likely died in 1792 reflecting an extended period of time to settle his estate. After Willis Streater’s death, Ned Streater lived on the farm of Stephen Graham from 1793 to 1810 and “acted as a free man being permitted to manage his own affairs and to hold property & that for other portion of the said time he was treated with great humanity and unusually indulged.” After the death of Stephen Graham, Ned Streater sued for his emancipation based upon his honorable Revolutionary War service.[8] He was awarded his “freedom from bondage”and $165 in compensation for damages in May 1814.[9] As a “free man of color” Ned filed suit again in 1824 seeking compensation for his period of bondage from 1783 to 1792 and the court ordered an award of $105. The court awarded an additional $210 for the period 1792 to 1810. Virginia had finally lived up to the promises made upon his enlistment and formalized into law in 1783.[10]

The Commonwealth of Virginia passed legislation in October 1783 that emancipated slaves who successfully served as substitutes for free persons and were forced to return to enslavement. The law specifically stated “that on expiration of the term of enlistment of such slaves that the former owners have attempted again to force them to return to a state of servitude, contrary to the principles of justice, and to their own solemn promise.”[11] This clause implies that enslaved people who served as substitutes were often denied the freedom they were promised as a result of their service, as in Ned’s case. This particular statue was passed into law shortly after the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war and highlights a recognition by Virginia’s lawmakers of the military contributions of an undetermined number of Virginia’s enslaved veterans. This acknowledgment of the legacy of enslaved soldiers is alone a testament to their value and contributions to the Patriot victory, however large or small their numbers.

The revolutionary era population of Virginia was about 600,000 with at least one third of that total, or over 200,000, African Americans, most enslaved.[12] While there are few surviving military records for Virginia’s substitute African Americans, service was probably more widespread than surviving records support.[13] This makes Ned Streater’s pension application even more valuable for researchers attempting to define the contributions of African American revolutionary soldiers.[14]

As with many surviving pension applications, not all the details one would like to know about a soldier’s life and revolutionary service were recorded. But Ned Streater’s statements and records provide enough detail for us to piece together his military service and journey to freedom as a result of it. He recalled the name of his company commander, Capt. Elvington Knott of the Princess Anne District that included Nansemond County, his home.[15] Col. William Woodford of the 2nd Virginia Regiment, in command at Great Bridge, was authorized to call up the Princess Anne District Militia as part of the campaign of 1775-1776 to liberate Virginia from royal governance.[16] Ned Streater specifically stated, “I was present at the battle of the ‘Great Bridge’ in Norfolk County when Fordice was killed.” Capt. Charles Fordyce of the British 14th Regiment of Foot led the failed assault on the morning of December 9, 1775 and died a few yards from the Patriot earthworks at the south end of the Great Bridge causeway.[17]

Considering he made his statement in 1833, his account of events fifty-eight years earlier is remarkably detailed and consistent with records of that event left by others. He continued his record of service by addressing events of 1780-81. This second period of service took place during the British occupation of Virginia by Generals Benedict Arnold, William Philips, and Charles Cornwallis. He named a number of Patriot field grade officers who were known to operate at that time period in the region.[18] He also addressed a skirmish at “Pip Pot Swamp” where he was wounded with a ball through the leg, “which deformed and very much disabled that leg.”

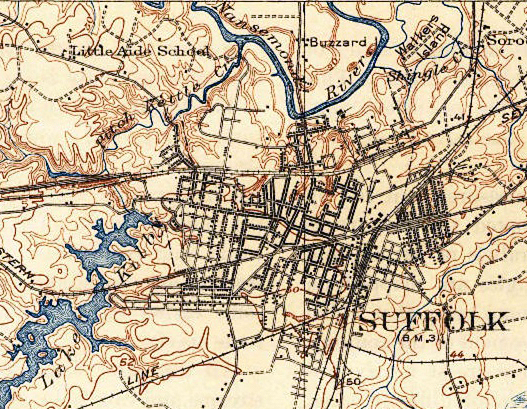

“Pip Pot Swamp” is likely a corruption or version of the contemporary Pitchkettle Creek and marsh just north and west of modern downtown Suffolk, Virginia. Pitchkettle Creek is a tributary of the Nansemond River. Today, the area remains a marshy swamp near the creek but modern drainage systems, including several dams and resulting fresh water reservoirs, reduced the size of the swamps that once existed there.[19] Many small skirmishes during this period of British military occupation south of the James River remain unrecorded. Local militias used their familiarity with the thick marshy terrain to their advantage when confronting occupying British and Loyalist forces. Perhaps Ned’s pension application provides insight into another yet-undocumented skirmish in the swampy terrain near downtown Suffolk, producing at least one casualty.[20]

Ned Streater’s pension application provides a glimpse into the experiences of one enslaved Revolutionary War soldier from Virginia. He served two periods of service, one in 1775-76 as Virginia’s Whig government used military force to ejected Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, from the colony of Virginia. His second period, during 1780-81, took place as the war once again shifted focus to the south during the British campaign to occupy Virginia. The main operating base for the British in Virginia was in Portsmouth until the move to Yorktown in August of 1781. Portsmouth borders Nansemond County, placing local militia operating there within easy reach of the occupying British forces. Ultimately, this British campaign ended with Lord Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, contributing to the end of major hostilities and ultimately the recognition of the United States as an independent nation.

Ned Streater’s journey to liberation and independence likely parallels the path taken by other enslaved African American veterans. The American Revolution was fought in part to implement lofty ideals concerning freedom and independence, and Ned Streater’s journey is part of that story. Publicly acknowledging and expressing appreciation for all Revolutionary War veterans is an American tradition, regardless of race or ethnicity.

[1]Ned Streater Pension Application, S7645, revwarapps.org; The others are James Bass (Pension Application S1745) and William “Billy” Flora, both free African Americans. James Bass is listed as “Free Colored” on the 1830 federal census, but may also have had Native American lineage.

[2]Norman Fuss, “Billy Flora at the Battle of Great Bridge,” Journal of the American Revolution, October 14, 2014, allthingsliberty.com/2014/10/billy-flora-at-the-battle-of-great-bridge/.

[3]William S. Forrest, Historical and descriptive sketches of Norfolk and vicinity: including Portsmouth and the adjacent counties, during a period of two hundred years: also, sketches of Williamsburg, Hampton, Suffolk, Smithfield, and other places, with descriptions of some of the principal objects of interest in eastern Virginia (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1853), 79, www.google.com/books/edition/_/vO9HAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Flora.

[4]“The revolution’s darkest shadow is unquestionably slavery, the failure to end it or at least to adopt a gradual emancipation scheme . . . slavery remains a permanent stain on the legacy of the founders, as most of them knew it would.” Joseph J. Ellis, American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 10.

[5]Emily J. Salmon and Edward D.C. Campbell, Jr., eds., The Hornbook of Virginia History: A Ready Reference Guide to the Old Dominion’s People, Places and Past (Richmond: Library of Virginia, 1994), 167.

[6]Genealogy Trails History Group, Nansemond County, Virginia, genealogytrails.com/vir/nansemond/#:~:text=Nansemond%20County%20was%20once%20located%20in%20the%20Virginia,Cittie%20in%20the%20area%20which%20became%20Nansemond%20County.

[7]United States Senate, The Pension Roll of 1835, 4, 1968 (reprint, with index, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1992), 3:514; Ned Streater Pension Application, S7645.

[8]Bins Genealogy, 1790/1800 Virginia Tax Lists Censuses, 1800, Streator, Willis (estate), Nansemond County, www.binnsgenealogy.com/VirginiaTaxListCensuses/; Ned Streater Pension Application, S7645.

[9]The date of Ned Streater’s lawsuit for his freedom coincides with slave escapes to the British during the War of 1812, as British warships and raiding parties patrolled the Chesapeake Bay region. Ned likely enjoyed some freedoms without having been formally emancipated as a result of his revolutionary service. Slave owners began to suppress those freedoms during this period as hundreds and possibly thousands of enslaved Virginians fled to the British fleet. See: Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy, Slavery and the War in Virginia, 1774-1832 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013), 268-273.

[10]Ned Streateer Pension Application, S7645 contains copies of his court documents from 1814 and 1824, likely the only surviving copies of these important court records.

[11]William Walter Henning, Henning’s Statutes at Large, being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the first session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, 11, 308, transcribed for the internet by Freddie L Spradlin, Torrance, CA, 2009, www.vagenweb.org/hening/vol11-15.htm.

[12] Population estimates for Virginia in 1775 vary; 600,000, including 400,000 of European decent and 200,000 African-Americans, is a reasonable number, making Virginia the most populous colony/state with at least one-third of the population African-American: see, Everts B. Greene & Virginia D. Harrington, American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790, (Gloucester, MA, Peter Smith, 1966), 6-8, 141; Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, DC: Center for Military History 1983), 94; Patrick Henry to Bernardo Galvez, January 14, 1779, in Ian Saberton, ed., Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War (Uckfield, England: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010), 3:300.

[13]Researchers estimate about one in six veterans lived long enough or actually filed pension applications. If we multiply the known number of cases by six, this may provide some insight into the numbers of enslaved African Americans who served as substitutes during the American Revolution.

[14]John U. Rees, They Were Good Soldiers’: African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783 (Warwick, England: Heilon & Company Limited, 2019). Rees addresses the challenges faced when researching African-Americans with Revolutionary War service.

[15]Capt. Elvington Knott served the Princess Anne District Minute Battalion during 1775-76 and as a militia officer later in the war. The Princess Anne District included the counties of: Princess Anne, Norfolk, Nansemond, Isle of Wight, and Norfolk Borough. E. M. Sanchez-Saavedra, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1783 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1978), 11-12, 21.

[16]Brent Tarter, “The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment: September 27, 1775-April 15, 1776,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85, no. 2 (April 1977), 173n54.

[17]Ned Streater Pension Application, S7645.

[18]Among other officers, Sreater named Maj. Alexander Dick who had an extensive record of Patriot service to Virginia throughout the revolution in a variety of units. See Sanchez-Saavedra, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations, 122-3, 175.

[19]United States Geologic Service Maps, contemporary map, maps.usgs.gov/map/, and historic 1919, ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=34a98f0efd84cda083718cbffcf6ab2d; the best revolutionary era map located to date, Library of Congress, Plan of Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties(1780)www.loc.gov/item/2012589670/, unfortunately lacks fine points for the target area of Nansemond County.

[20]The most detailed first-hand accounts of the military actions south of the James River during early 1781 may be found in two published works. Unfortunately there are few specifics in surviving Patriot accounts of these smaller and irregular military actions and many engagements likely went completely undocumented or unnamed. See: Johann Ewald and Joseph P. Tustin, ed & trans., Diary of the American War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 255-316; John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal: A History of the Operations of a Partisan Corps, called the Queen’s Rangers (New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844), 158-248, ia902607.us.archive.org/2/items/simcoesmilitary00simcgoog/simcoesmilitary00simcgoog.pdf.

One thought on “Virginian Ned Streater, African American Minute Man”

Very interesting article, Patrick. Important subject.