The planned capture of New York City in 1776 by British forces set the stage for what was to become the largest battle of the Revolutionary War period. British and Hessian forces were able to defeat their American opponents easily in open conflict in the early stages of the Battle of Long Island in 1776. The attackers were also able to outflank the American Army and set themselves directly in front of the Brooklyn defensive line, an extensive line of forts and entrenchments encircling the narrowest part of the Brooklyn peninsula. The Brooklyn line of forts utilized the natural landscape to great advantage. The jubilant British force, so successful in their generalship, was ultimately halted at this line. The British decided against continuing their advance and ordering an assault on the lines. Instead, they set up for a general siege of the forts. Many have contemplated that the British were wary of duplicating losses suffered in their assaults on Breed’s Hill near Boston in 1775.

In light of this history, this author has continually questioned what was the physical reality of this defensive line. Were the American works indeed exceptional or were the attackers being overly cautious in their moves after the battle? What did the actual fortifications look like? These questions lack clear evidence. Research of the physical constructions themselves is challenging. The works were destroyed after they were abandoned by the Americans and the region was fully in British control. In time even the natural landscape was removed in the development of New York City.

One of the immediate questions is why Brooklyn was attacked and not the city of New York directly? The principal reason that New York was not attacked directly or from behind was because lower Manhattan and its inner harbor had been strengthened and fortified by American defenders.[1] Works in early 1776 were set up in New York City along its shores, and Governors Island and Red Hook had a series of fortifications defending the harbor and passage along the East River.[2] All these defenses were established to prevent the enemy from landing close to New York. In order to protect the city from an attack overland from Long Island a continuous defensive line, strengthened by forts, was constructed at the narrowest part of the Brooklyn peninsula. The British, who were limited in their control of the waterways due to these inner harbor defenses, chose to attack from the southern part of the Brooklyn peninsula instead.

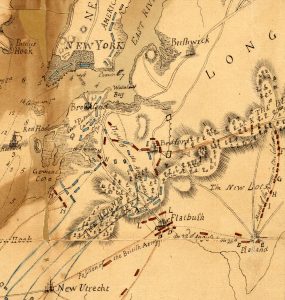

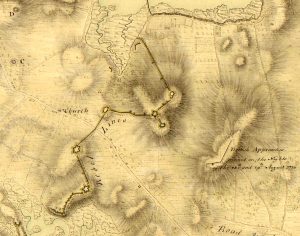

There are period maps which aid in understanding the positioning of the forts and the layouts of these works within the line. A map made by British engineer George Sproule shows a detailed version of the forts. The notes on the map include the description, “Drawn by Lieut. Geo. Sproule of the 16th Regimt. of Foot assist. engineer from a survey by him in September 1776. Drawn in March 1781.”[3] He noted that all the defenses in the line of forts had been demolished by 1781. Another period map published in the diary of Dr. Ezra Stiles shows little in the way of detail, but may have been one of the earliest renderings of the line of forts and gives their names.[4] The sketch also shows the number of guns within the forts. The map lacks the landscape details afforded by the Sproule map. Together these period maps add greatly to our understanding of the early Brooklyn landscape and the layout of the lines at the time of the battle.

Maj. Gen. Charles Lee may have been the first individual in the American Army to be assigned the task of preparing for an attack on New York City. In February 1776 he wrote to General Washington, “We have fixed a spot on Long Island for a retrenched Camp which I hope will render it impossible for ‘em to get footing on that important Island as this Camp can always be reinfor’d it is our intention to make it so capacious as to contain four thousand men.”[5] In the same correspondence Lee recommended Capt. William Smith be sent from Cambridge to serve as chief engineer at New York. Lee spoke highly of his Smith as an “excellent, intelligent, and active officer,” and early on had him survey and report upon the positions at Hell Gate and on Long Island.[6] The early fortified line’s planning and individual fortification layouts along the line were most likely designed by General Lee and engineer Smith. Besides his work in New York and Brooklyn, Smith took charge of engineering duties in the Hudson Highlands for a brief period beginning in February, 1776. Smith had replaced Bernard Romans there who had been relieved of engineering duties by officials in New York. Smith did a survey and issued subsequent plans for Fort Constitution as well as developing an initial layout for Fort Montgomery in the Hudson Highlands.[7]

The work of fortifying New York and the defensive positions on Long Island required massive planning and manpower. An order from Headquarters dated March 15, 1776 read:

It is intended to employ one-half of the inhabitants every other day, changing, at the works for the defence of this city; and the whole of the slaves every day, until this place is in proper posture of defence. The Town Major is immediately to disperse these orders. Four cannon, of thirty two-pounders, two of eighteen-pounders, and two of twelve-pounders, are, to-morrow morning as soon as possible, to be sent over to Long-Island for the defence of the works there, to be placed as the Chief Engineer (Colonel Smith) will direct.[8]

Upon General Washington’s arrival in New York in early April a change in leadership of the defense works was made. As of late April Washington appointed Col. Rufus Putnam chief engineer of the New York Department. Putnam was favored by Washington to become chief engineer for New York since his successful fortification planning at Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston in early 1776.[9] The initial position of the Brooklyn line was set up as an encampment for the 3rd brigade of the Continental Army beginning on April 25, 1776. The established line of fortifications was designed to establish three principal forts and two redoubts set along a range of hills at the narrowest point of the Brooklyn peninsula. Together the line created a continuous defense a mile and half wide from the Gowanus Creek in the south to Wallabout Bay in the north. Two of the works were erected on the right side of the main road out of Brooklyn. These forts were named Fort Greene and Fort Box. Three were on the left side of the road were named, in order, the Oblong Redoubt, Fort Putnam and the apparently nameless redoubt “on its left.”[10] Connecting the forts was a continuous entrenchment of breastworks. The forts were suited well to the landscape and were near enough to each other to command the ground between them.

The Sproule map clearly shows Fort Box, Fort Greene and Fort Putnam as star shaped forts.[11] Fort Greene to the left of Fort Box is described as mounting six guns and was the largest of the forts. The Oblong redoubt shared with Fort Greene the important defense position at the center of the line. Fort Putnam was a little smaller than Fort Greene and mounted four to five large guns. It was situated at the strongest naturally defensive position, at the highest point of the hills and ahead of the overall line. The last work, the ‘redoubt on the left” was on a spur of elevation extending out from Fort Putnam.[12]

Aside from the period maps there is little in the way of details of the fortification methods used. No eighteenth or nineteenth century writings describing the works at Brooklyn tell us how the forts and their walls appeared at the time.

Writings about the Hudson River forts, Montgomery and Clinton, tell us about construction techniques used by the American army in 1776. Forts Montgomery and Clinton were partly designed by the same Capt. William Smith who worked on the Brooklyn forts. A July 1776 letter to General Washington concerning Forts Montgomery and Clinton noted, “Those works built are all faced with fascines, and filled in with strong, good loam; but as they are liable to take fire, the Commissioners who have the care and direction of the works, propose to rough cast the faces of the embrasures with a strong mortar made of quicklime and sharp sand, of which there is plenty at hand.”[13] The fascine was a common element of military fortification, a bundle of saplings bound together. A 1783 military text described them:

Fascines are a kind of faggots, made of broom, brushwood, small branches of trees, &c. tied in 2,3,4,5, or more places, and are of various dimensions, according to the purpose for which they are intended: they measure, in length, from 2 to 18 feet, and are from 6 to 18 inches in diameter.[14]

Excavations and analysis in 1958 by John Mead at the ruins of the Grand Battey at Fort Montgomery discovered mortar layers at the positions of gun embrasures, and within these layers the impressions of saplings from bundles of fascines.[15] Ruins of stone walls at the site indicated that the lower portion of the embankment walls above the ditch existed to a course height of approximately five stones and that that these embankment platforms were about sixteen feet wide. Above the lower stone berms it was determined that stacked bundles of fascines were positioned on both sides of the embankments up to breastwork height.[16] In Captain Smith’s report on his survey of the Highlands at Fort Montgomery in March 1776 he added, “that he thinks the fort may be built at an easy expense, as wood and fascines are handy,” and that, “These forts are recommended to be built of sods and fascines, which nature has plentifully supplied at Pooplopen’s Kill.”[17] Today, Fort Montgomery Historic Site museum displays a diorama of the attack on Fort Montgomery in 1777 and clearly shows this early fort wall construction technique revealed by archaeological research. A period rendering by British engineer Archibald Robertson of the American fortification at Horn’s Hook shows a convincingly similar look to its walls with the facings of either stacked fascines or stacked timber. The walls there were also pierced with a continuous line of fraizing, outward pointed sharpened palisades.[18]

It is with a degree of certainty based on this collective research that most of the methods of construction discussed above were utilized at the Brooklyn forts. The forts were also surrounded by “the most formidable abatties” as confessed by the capable British engineer John Montresor.

Tactics planned for troops stationed in at the forts improved their defense. Orders from General Greene in early July commanded that regiments mark a line around each of the forts for the troops to begin musket fire if the forts were to be besieged by the enemy. The approximate distance of the marked lines from the forts was eighty yards. General Greene also recommended troops to load for their first fire with one musket ball and four or eight buckshot. This amount of fire if received from twenty to thirty yards distance was expected to repel the enemy.[19] The defenders also planned to use pikes (spears) if the forts were assaulted Three hundred spears, with a grindstone for sharpening them, were ordered from the quartermaster, and the pikes placed as follows: “Ft. Greene, 100; Ft. Box, 30; Oblong Redoubt, 20; Ft. Putnam, 50; ‘works on left,’ 20.”[20]

On June 1, 1776 General Greene gave orders for the troops to man the fortifications. Five companies of Col. James Mitchell Varnum’s 9th Continental Regiment were posted in Fort Box and three other companies of this regiment to the right of Fort Green. Five companies of Col. Daniel Hitchcock’s 11th Continental Regiment were posted to Fort Putnam, and three companies of this regiment at the redoubt upon the left of it. Five companies of Col. Moses Little’s 12thContinental Regiment were positioned in Fort Greene and three companies of this regiment in the Oblong Redoubt.[21]

After the British attack and the land battles of Brooklyn on August 27, 1776 the attackers halted in front of the line of forts. British general Sir William Howe’s description of his approach read,

These battalions . . . pursued numbers of the rebels . . . so close to their principal redoubt and with such eagerness to attack it by storm, that it required repeated orders to prevail upon them to desist from the attempt. Had they been permitted to go on, it is my opinion they would have carried the redoubt, but as it was apparent the lines must have been ours at a very cheap rate by regular approaches, I would not risk the loss that might have been sustained in the assault.[22]

With this decision the British forces prepared for a regular siege on August 28-29 and skirmished against the American forts. The British utilized a height of land to set their siege lines that was either overlooked or too far out of the line to be defended with the American fortifications.[23] These siege lines and the height of land can be recognized on the Sproule map of 1781. On the night of August 29-30 General Washington made his successful withdrawal of the Brooklyn troops from the American lines thus ending any further attack plans by the British.

The debate seems to continue on Gen. William Howe’s decision to not attack the Brooklyn forts following his battlefield successes on August 27. Historically, Howe’s decision was criticized by some of his contemporaries and defended by others. Capt. John Montresor, who was with General Howe in Brooklyn, described the lines as well built, entirely complete, proof against cannon, and surrounded with formidable abbatis. He defended General Howe’s actions asserting that, “They could not be taken by assault, but by approaches, as they were fortresses rather than redoubts.” Montresor later also testified that the British force lacked fascines which would have allowed the attackers to cross over the American ditches, nor did they have scaling ladders needed for an assault.[24] This could have been a determined response for a failure to attack, but it could also attest to the considerable strength of the forts.

Some evidence supported Howe on the grounds that he was unable at the moment to determine how great his adversary’s strength was. Gen. James Robertson, present at the time, stated,

I marched at the head of my brigade to a place near the enemy lines. I went to the situation where I thought I could best see without leaving my brigade far, and I could not make any judgement of the strength of the enemy’s lines from any place I could see them. This made me wish the Grenadiers would not go on . . . I imagine that the General called back the troops because he was unable to form a just estimate of the force of the lines.[25]

It seems most likely, at least in the mind of this author, that the British Commander was being cautious in his approach since he lacked sufficient information of the overall strength of the line of forts. Due to a combination of the naturally defensible landscape in union with the overall scale and length of the line of the fortifications, it most likely had a very formidable outside appearance. Speculating on the most likely method of construction allows us to come closer to understanding the physical reality of this lost line of forts.

[1]Richard K. Showman, ed., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 222.

[2]Henry Phelps Johnston, “The Campaign of 1776 in New York,” Memoirs of the Long Island Historical Society Volume III (Brooklyn: Long Island Historical Society, 1878), 75.

[3]“A plan of the environs of Brooklyn showing the position of the rebel lines and defences on the 27th of August 1776,” University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, quod.lib.umich.edu/w/wcl1ic/x-8657/wcl008728.

[4]Ezra Stiles, The Literary diary of Ezra Stiles, Franklin Bowdtich, ed. (Dexter, NY: New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 152.

[5]Charles Lee to George Washington, February 14, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives.

[7]Paul K. Walker, Engineers of independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (Honolulu, HI: University Press of the Pacific. 2002), 204.

[8]Peter Force, American archives: consisting of a collection of authentick records, state papers, debates and letters and other notices of publick affairs, the whole forming a documentary history of the origin and progress of the North American colonies, of the causes and accomplishment of the American Revolution, and of the Constitution of government for the United States, to the final ratification thereof Vol.5 Series 6 (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Carke and Peter Force, 1837), 219.

[9]Raleigh B. Buzzard,“Washington’s Favorite Engineer,” The Military Engineer 40 no. 269 (1948): 115-18, www.jstor.org/stable/44556026.

[10]Johnston, “The Campaign of 1776 in New York,” 68-73

[11]Historian Henry Phelps Johnston assumed that Fort Box was a diamond shaped fort.Ibid., 69.

[13]George Clinton, Hugh Hastings, and James A. Holden, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795, 1801-1804 Volume 1 (New York and Albany: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., 1899), 135.

[14]Lewis Lochee, Elements of Field Fortification (London: T. Cadell and T Egerton, 1783), 142.

[15]Charles Fisher and Gregory Smith, The Most Advantageous Situation in the Highlands: An Archaeological Study of Fort Montgomery State Historic Site (Albany, NY: The Museum, 2004), 87-88.

[17]Merle G. Sheffield, The Fort That Never Was: A Discussion of the Revolutionary War Fortifications Built on Constitution Island, 1775-1783 (West Point, NY: Constitution Island Association, 1969), appendix F.

[18]”View of the rebel work round Walton’s House, with Hell Gate & the Island [illegible],” Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/be0f6d75- d1d0-1529-e040-e00a18065909.

[19]“General Greene’s Orders (Colonel Little’s Orderly Book)” in Johnston, “The Campaign of 1776 in New York,” Part 2, 19.

[20]Showman, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 213, 230.

[21]“General Greene’s Orders (Colonel Little’s Orderly Book)” in Johnston, “The Campaign of 1776 in New York,” Part 2, 15.

[22]William Howe to George Germain, September 3, 1776, C.O.5/93, British National Archives.

[23]Jeremiah Johnson, “Recollections of Brooklyn and New York, in 1776: from a note book of Gen. Jeremiah Johnson, of the Wallabout, L.I.,” Naval Magazine I (1836), 370.

[24]Troyer Steele Anderson, The Command of the Howe Brothers During the American Revolution (Cranbury, NJ: Scholar’s Bookshelf, 2005), 138.

3 Comments

This is a link to the whole of the Sproule map. You can see that the Lines were primarily constructed to protect the landward approach to Fort Stirling. The heavy guns at Fort Stirling (and at Red Hook) were essential to preventing the British ships access to the East River. Without that access they would have had to travel up the Hudson river to attack Manhattan Island from the north and west… thus running the guns at “The Battery,” Governor’s Island and Forts Lee and Washington. General Lee envisioned no defense of the Brooklyn Heights. Only the defense of the fortress he created around the Brooklyn Peninsula. As long as this complex of forts (large enough to hold 4 thousand men) held out, Manhattan was safe. After being transferred by Congress to Charleston, SC, Lee’s basic strategy for the defense of New York was lost/forgotten, and General Washington acquiesced when General Greene suggested troops be shifted from Manhattan to Brooklyn in an attempt to defeat the British in open battle. Even after their subsequent and predictable defeat Washington could have had the bulk of the troops then on Long Island withdraw into and man this complex of forts, adhering to Lee’s plan once more. However, he inexplicably chose instead to abandon Long Island, thus opening up the East River to the British and ultimately dooming Manhattan to British occupation.

https://mapcollections.brooklynhistory.org/map/a-plan-of-the-environs-of-brooklyn-showing-the-position-of-the-rebel-lines-and-defences-on-the-27th-of-august-1776/

In my reading of the period orders and the 19th century histories there appears to be no writings of changes in strategy between commanders on the defense of Brooklyn and New York throughout early 1776. I read the fortifying of New York and its surroundings as an ongoing cumulative measure of defense which was desperate and took months of planning and manpower adhering to ongoing changes in command but all ultimately with the same strategy for its defense. Probably the plans for defense changed weekly as work progressed.

Whether Washington could have withstood the British army at the line of forts after the land battles is for sure a question and worth a debate… I personally think the British troop strength numbers were too great, and eventually the forts would have fallen under an ongoing siege. Washington may have sensed this and retreated to maintain his numbers.

“… eventually the forts would have fallen under an ongoing siege.” Yes, undoubtedly. The British were as experienced at conducting the investment of a fortress as the Americans were inexperienced in holding one. However, at this point in the campaign, and without the Battle of Brooklyn to shake them (assuming it didn’t happen but Lee’s strategy was adhered to), the high morale of the Continental Army would have mitigated against a similar fiasco such as the collapse of Fort Washington a little later. Who knows, rather than that defeat the siege could have been more like that of Forts Mifflin and Mercer. General Howe was methodical in nature, and the investment of these works would have taken weeks if not months… each passing moment strengthening the legitimacy of independence. Lee was initially given the task of constructing a system of defense for the indefensible. I find it puzzling that somehow Washington didn’t get the memo that Fort Stiring was the key to the whole thing. Maybe it was lost when he replaced Lee’s engineer Capt. William Smith with his own favorite, as you point out.