One of the greatest sources of information on the American Revolution is the collection of pension applications submitted by American veterans of the war or their families. Over 80,000 files are available to researchers as part of the National Archives and Records Administration microfilm publication M804. Intent on finding some desired morsel of information, however, few researchers probing the collection give much thought to just how these files came into existence in the first place.

The idea of offering pensions to veterans did not originate in the Continental Congress. The British army offered pensions beginning in the late seventeenth century, and the system was well-established by the second half of the eighteenth century. Following England’s example prior to the Revolution, the North American colonies provided some relief for soldiers injured while in the service. For example, in May 1755, Virginia’s governor Robert Dinwiddie in a speech read before the House of Burgesses said, “The poor Men who suffered at the Meadows with Colonel Washington I recommend to your Favor, as they were disabled in the Service of their Country.”[1] By June, the Burgesses had granted recompense to some of the petitioners.[2]

As fighting in the French and Indian War intensified, more attention came to be paid to the situation of the wounded. On January 10, 1757, in a portent of things to come in less than two decades, George Washington wrote to the British commander in chief, the Earl of Loudon:

No Regular Provision is established for the maimed and Wounded, which is a discourageing Reflection and feelingly Complained of. The Soldiers very justly observe, that Bravery is often rewarded with a broken Leg, Arm, or an Incurable Wound, and when they are disabled and not fit for Service they are discharg’d, and reduced to the necessity of begging from Door to Door, or perishing thrô Indigence—It is true, no Instance of this kind has yet appeard—on the contrary, the Assembly have dealt generously by such unfortunate Soldiers who have met with this Fate—But then this is Curtesy—in no wise Compulsory, and a Man may suffer in the Interim of their Sittings.[3]

Compensation for disabled soldiers continued to be an intermittent consideration by the individual colonies up to the start of the Revolution.[4]

The transformation of the disagreement with England from a war of words to armed conflict brought a new approach to compensation for those disabled during service. The Continental Congress began looking at a centralized process and, in November 1775, the “Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies” included a section that set a dollar amount for those officers, marines, and sailors disabled or killed. If killed, the widow or children received the money.[5] Congress dealt with applications on an individual basis.

As weeks went by with the war expanding and hopes for a quick resolution fading, Congress saw the need for a more expansive plan to care for those disabled in combat not just in the navy, but in the land forces as well. Not all agreed with the idea, and Gen. Nathanael Greene wondered why: “Is it not inhuman to suffer those that have fought nobly in the cause to be reduced to the necessity of geting a support by common Charity. Does this not millitate with the free and independant principles which we are indeavoring to support? Is it not equitable that the State who receives the benefit should be at the expence? . . . I cannot see upon what principle any Colony can encourage the Inhabitants to engage in the Army when the state that employs them refuses a support to the unfortunate.”[6] In June 1776, Congress finally appointed a committee of five to “consider what provision ought to be made for such as are wounded or disabled in the land or sea service, and report a plan for that purpose.”[7]

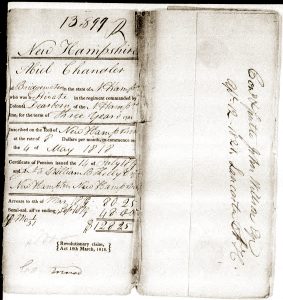

The committee set to work and on August 26, 1776, Congress enacted the first national pension legislation.[8] It provided for half-pay to be distributed to officers and enlisted men of the army and navy who became disabled during their service and could no longer serve or earn a living as a result of the injury, and for men who were “wounded in any engagement . . . though not totally disabled.” The pay would continue for the duration of the disability. The soldier submitted his petition to a person or board in his state of residence then decided how much to pay him providing it did not exceed the half-pay. The petitioner had to provide a certificate from his commanding officer and the surgeon who cared for him giving the nature of the wound and the engagement in which he received it. Getting Congress off the financial hook—for a while, at least—the legislation said that each state should make the payments “on account of the United States.” The states would be reimbursed at some point in the future

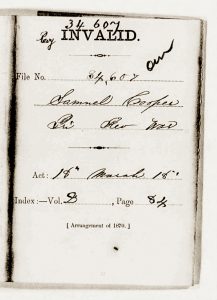

The legislation had an interesting proviso: officers and soldiers eligible for a pension but capable of doing garrison or guard duty would become part of a corps of invalids. In like manner, disabled sailors would be given non-combatant duties.[9]

Over a year passed before Congress next addressed pensions. On January 5, 1778, a comprehensive motion regarding pensions—this time for uninjured soldiers—came to the floor for consideration.[10] Debate continued for another five months until a trimmed-down version finally passed on May 15 in which Congress resolved to grant half-pay for seven years to officers who remained in the service until the end of the war. The resolution limited the amount that general officers could receive to the same amount as a colonel. It also required that the officer had taken an oath of allegiance and lived in the United States (thereby eliminating the eligibility of the plethora of foreign officers serving in the American forces). Non-commissioned officers and private soldiers who remained for the duration would receive a one-time reward of eighty dollars at the end of the war.[11]

The debate over pensions continued. A resolution on August 17, 1779, demonstrated the equivocation brought on by lack of funds, lack of centralized power, and the indecisiveness of the members of Congress. The act said that states should reward their soldiers, “either by granting to their officers half pay for life, and proper rewards to their soldiers; or in such other manner as may appear most expedient to the legislatures of the several states.”[12] A second resolution regarding the widows of soldiers had a similar tone recommending that the states make such provision “as shall secure to them the sweets of that liberty” for which their husbands died.[13]

In the summer of 1780, Congress again took on the issue of support for the families of officers who died while in the service (the discussion did not include enlisted men). On August 24, the members voted that the provisions of the May 15, 1778, act (half-pay for seven years) would also apply to the unmarried widows of men who died—whether while in the service or after the war. Should the wife also die, the half-pay would go to any orphaned children.[14] Two months later, Congress increased the duration from seven years to life.[15]

Post-war support became a quite serious issue for Congress late in 1782. Men in the army kept track of the legislative action regarding post-war support and it became part of a letter of grievances submitted to Congress by a committee of officers:

We are grieved to find that our brethren, who retired from service on half-pay, under the resolution of Congress in 1780, are not only destitute of any effectual provision, but are become the objects of obloquy. Their condition has a very discouraging aspect on us who must sooner or later retire, and from every consideration of justice, gratitude and policy, demands attention and redress.

We regard the act of Congress respecting half-pay, as an honorable and just recompense for several years hard service, in which the health and fortunes of the officers have been worn down and exhausted. We see with chagrin the odious point of view in which the citizens of too many of the states endeavor to place the men entitled to it. We hope, for the honor of human nature, that there are none so hardened in the sin of ingratitude, as to deny the justice of the reward.

To correct this situation, the officers wrote that they would be willing to drop the half-pay-for-life provision in favor of full pay for a given number of years or a one-time lump-sum payment.[16]

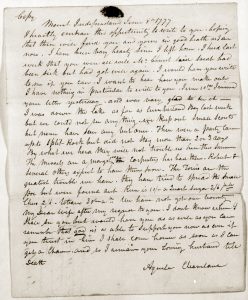

The officers’ letter did not materialize in a vacuum. It emerged as part of one of the darkest events for the army—the so-called “Newburgh Conspiracy” during which the possibility of wide-spread mutiny threatened the army. In March, Congress received from Washington a letter and several documents concerning the dangerous activity. He had successfully averted the serious problem and, in one of the letters, wrote down his feelings on the pension issue which echoed what he had written in 1757. Quoting the officers’ letter, Washington wrote:

if the officers of the army are to be the only sufferers by this revolution; if retiring from the field they are to grow old in poverty, wretchedness and contempt; if they are to wade through the vile mire of dependency, and owe the miserable remnant of that life to charity, which has hitherto been spent in honor,’ then shall I have learned what ingratitude is, then shall I have realized a tale which will embitter every moment of my future life. But I am under no such apprehensions; a country rescued by their arms from impending ruin, will never leave unpaid the debt of gratitude.[17]

A committee took up the issue and returned a suggested resolution recommending full pay on March 22, 1783. Congress quickly passed a shortened version formalizing the proposal. Officers could accept a commutation of half-pay for life in favor of full pay for five years and added the alternative of issuing securities bearing annual interest of six percent.[18] The act helped soothe any left-over mutinous inclinations within the army.

The promise of peace and the imminent disbanding of the army in 1783 prompted even more attention to post-war support for the men. On April 23, a committee reported that the army expected three months’ full pay when disbanded. Congress felt that “the expectations of the army are reasonable and very moderate and it is the ardent wish of Congress to make them as happy at the time of their retirement as possible.” They resolved to grant all discharged soldiers, including enlisted men, their wish.[19]

In the eight years since the first efforts at a pension plan several pieces of legislation had been enacted, so Congress began work on creating one document for administering the pension plan. It took two years but the resolution passed on June 7, 1785, with some changes. Proof of disability now could be shown through “good and sufficient testimony.” Further, Congress created a tiered system of pay whereby less seriously disabled officers and men received a proportionately smaller amount. Lastly, each person receiving a pension had to annually take an oath before his county magistrate swearing to his disability.[20]

The formation of a new government under the Constitution led to Congress taking a new look at pensions. On September 29, 1789, President Washington signed into law a single paragraph sent to him by Congress. The new law announced that the federal government, instead of the states, would pay the pensioners directly. The rest of the existing legislation would remain in effect and be reviewed annually.[21]

Congress continued to tinker with the pension legislation. In March 1792 they passed an act saying that veterans not already receiving pensions should apply for them directly to the federal government rather than their home state. It also said that enlisted men could not transfer their pensions to others.[22] There was no such restriction on officers.

Fourteen years passed before the next major alteration came along. Early in 1806, the House sent a bill to the Senate which, over the next three months, added several amendments. With little debate, the House accepted the Senate version on April 10, 1806. No other legislation since the original act in August of 1776 had as much impact on pensions as did this bill. The House version had been little more than an extension of the existing legislation but the Senate took a different tack once they received it. Most importantly, the amendments expanded the scope of the original laws to include veterans of state units as well as militia. Further, because the numerous modifications of the original wartime legislation had made applying for and administering pensions somewhat confusing, the new act voided all the previous legislation. Congress started anew.[23]

The next big step came in 1818. Prior to that time, a pension could be awarded solely on the basis of disability or death (with the exception of officers who served for the duration). The new act provided that ALL officers and enlisted men who served in the army or navy, disabled or not, would be eligible for a lifetime pension. Some important provisos appeared in the bill. First, an applicant had to prove he had served a total of at least nine months (which did not have to be consecutive). More importantly, he also had to show that he “by reason of his reduced circumstances in life, shall be, in need of assistance from his country for his support.” Lastly, applicants had to relinquish any other pension claims they may have. Officers received twenty dollars per month and enlisted men eight.

The act also set out the administrative process. The applicant had to make a declaration under oath before a judge describing his service, and provide other evidence of his service and need. If the judge felt the claim to be proper, he forwarded it to the Secretary of War who reviewed the application and, if satisfactory, added the applicant to the pension list.[24]

Anyone who has worked with the pension files extensively knows that this 1818 legislation prompted a large number of applications. So many, in fact, that the overall expense of pension payments increased dramatically. The financial stress and charges of false claims of poverty caused Congress to create a corrective act in 1820. The new legislation required that each person who had been granted a pension under the 1818 act, and each new applicant, submit a certified account of his estate and income. The Secretary of War would review the accounts and strike from the pension list any who, in his opinion, did not need assistance. Any pensioner who had been placed on the list prior to 1818 and who had dropped that pension in order to receive the benefits of the latest act would have the earlier pension restored.[25] The new directive reduced the number of pensioners by several thousand.[26]

The requirement for a certified account created its own set of problems. Large numbers of pensioners dropped from the list appealed the decision for a variety of reasons. One of the more common reasons was erroneous assessment of property. Another was that life conditions and financial situation constantly change. The volume of appeals prompted the House to pass a bill addressing the situation in March, 1822. Disliking the bill, the Senate postponed debate indefinitely; the House developed a second bill in December. Again, members of the Senate tried to kill the bill by offering several amendments.[27] An amended version passed the Senate but the House rejected one amendment. In two very close votes the Senate agreed and the bill became law.[28] The final version directed the Secretary of War to reinstate those who had been dropped but had subsequently proven their need for support provided that the applicant “has not disposed of or transferred his property, or any portion thereof, with a view to obtain a pension.”[29]

Six years passed before the next major modification to the pension legislation. On May 15, 1828, Congress granted full pay for life to the surviving officers and enlisted men of the Continental Line who had served for the duration, but limited the amount to a maximum of a captain’s pay. The act excluded enlisted men already on the pension list. Applicants did not have to provide proof of need, only their time in service.[30]

The final and most beneficial of the pension acts came nearly a half-century after the close of the war. Legislation enacted on June 7, 1832, expanded the 1828 provisions for full pay to more people by altering the time-in-service requirement to two years. Those who had served a shorter period but more than six months received pay on a graduated scale. This is the first act under the Constitution that allowed the pension to be paid to widows and children.[31]

Congress again addressed the situation of families of veterans in 1836. The act passed in August 1780 allowed the families of deceased officers to collect the veteran’s benefits but only for seven years. Following the expiration of that proviso in 1794, it took a special act of Congress for a widow to collect any pension. On July 4, 1836, Congress passed legislation that provided a pension for post-1818 veterans but included a section that allowed the widow of any veteran eligible for a pension to apply for her husband’s pension provided she had married the veteran prior to his leaving the service. Some of the most extensive applications resulted from this act as families tried to prove the veteran’s service and the timing of the marriage.[32]

A handful of acts of Congress happened in next forty years. Legislation in 1838 granted pensions for five years to widows whose marriage had taken place before 1794.[33] Another in 1848 provided pensions for life for widows married before 1800.[34] Legislation in 1853 and 1855 removed any restrictions on the date of marriage.[35] The last legislation relating to widows of Revolutionary War veterans appeared on March 9, 1878, and stated that the widows of veterans who had served for at least fourteen days or had been in any engagement could apply for a pension for life.

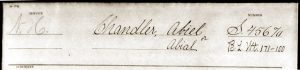

There are hundreds of thousands of pages to explore in the M804 pension files. Even more would have been available but for fires in 1800 and 1814 that destroyed most of the early papers. Those that exist contain both historical and genealogical information applicable to the interests of a wide variety of researchers. There are also nearly seventy journals, diaries, and other record books in the files. In addition to the original documents, the files are arranged alphabetically on 2,670 rolls of microfilm available for viewing at several NARA reading rooms across the country. They are also available and searchable on-line at the fee-based Fold3 website.

It takes patience to work with the pension files. They contain many pages that will not be of value to you but you will often not know that until you read them. Your nerves—and your eyes—will be tested trying to decipher the several styles of handwriting that appear in each file—even on a single page. You will be frustrated by the frequent lack of detail and occasional alterations discrepancies that reveal the effects of time on human memory. In spite of that, the information—even only bits and pieces—that you do recover will make it worth your while. As a bonus, reading the pension files will bring you quite close to the people of a different time. It’s time travel. Give it a try.

[1]“The Meadows” refers to the Fort Necessity battle fought on July 3, 1754, between a force commanded by Washington and a larger force of French and Indians. Governor Dinwiddie to House of Burgesses, in H.R. McIlwaine and John Pendleton Kennedy, eds. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia: 1752-1755, 1756-1758 (Richmond, VA: The Colonial Press, E. Waddey Co.1909), 231 (JHB).

[3]The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1984), 79–93.

[5]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (Washington, D.C., 1904-37), 3:386-7 (JCC).

[6]Nathaniel Greene to John Adams, June 2, 1776, The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 4, February–August 1776, ed. Robert J. Taylor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 4:227–31.

[8]With no real power, Congress used the word “recommended” when directing the legislation at the states.

[10]Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, roll 30, item 21, 177-9 (PCC).

[13]PCC, roll 30, item 21, 149.

[15]PCC, roll 28, item 19, 6:307.

[16]PCC, roll 55, item 42, 6:63-5.

[17]PCC, roll 171, item 152, 11:134-6.

[19]PCC, roll 27, item 19, 4:391-3.

[21]The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America, ed. Richard Peters, Esq. (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1845-1866), 1:95 (PSL).

[26]Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files(Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, 1974), 2. This is a very handy guide to the pension papers. It includes, among other things, a history of the collection and its administration, a list of the books in the collection files, and a listing of the range of files on each microfilm roll.

[27]Senate Journal. 17th Cong., 2dsess., February 21, 1823, 12:174-5.

12 Comments

Mike

A fascinating article! Do you believe historians need to be aware of any biases introduced by the loss of documents in the 1800 and 1814 fires? For example, disabled soldiers might be underrepresented in the remaining records as they may have applied for a pension under previous acts. I would be interested in any characterizations of the lost records and how they might impact the analysis of the remaining pension files. Maybe you have a view or could point me in the right direction.

Damn your eyes, Gene, for coming up with a question that makes me think and go back into my notes.

There are files for many of the pre-fire applications (they are, of course, all disability or death claims). They are marked “Dis. No Papers” and most have a card containing brief notes about the applicant—name, unit, rank, residence, etc. As far as I know, this information came from “American State Papers, Class 9, Claims” published by Congress in 1834 which gathered it from claims submitted to Congress in the early 1790s. Other information for later claims appears in “Report from the Secretary of War … in Relation to the Pension Establishment of the United States” which Congress received in 1835. This latter collection apparently resulted from investigations into specific veterans. It is regretable, however, that there are still a certain number of applications that are lost forever.

That being said, right now (I may change my mind as I ponder this further), I don’t think disabled vets are underrepresented to any great extent. As stated above, the basics of many claims have been reentered into the collection. On top of that, some of the men reapplied under later legislation. I suspect the number totally lost to the fires is relatively small. To me, rather than any bias being introduced by the circumstances, our greatest wound lies in the loss of details of the veterans’ experiences written about in the applications. Those can never be recovered.

Thanks for your analysis Mike. I got a chuckle over your intro! Maybe someday a data scientist will create an analyzable database to compile summary statistics. It would make all of our lives easier.

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been transcribing pension records through the National Archive’s Citizen Archivist online platform and have seen how detailed some of the pension files are regarding inventory schedules and their recollection of the War. I’m not sure, though, if the end result would be a searchable database. Has anyone looked into creating one?

Great read. The last paragraph is perfect; exactly what anyone wishing to look at these records should know.

Thanks, Andrew. To me (obviously), working in the pensions is well worth the effort.

Mike

This is one of the most interesting articles I’ve read recently, good job. Did you find any kind of discrimination – racial, religious, or economic – in pension applications and their legislations? To my knowledge, pensions were granted regardless of race, religion, and social status, but I’d like to hear from someone who has actually worked on pension files.

Matt,

From the thousands of applications I’ve read, the inclusion of the race of the applicant is fairly rare. This also holds true for the religion of the applicant. Fairly prevalent, however, are the clear indications of the pension applicant being “poor”.

In regard to racial discrimination, W. Trevor Freeman has written about it in his Master’s thesis in regard to North Carolina soldiers. I’ve referenced his thesis in an article on the demographics of the North Carolina Continental Line forthcoming here in this Journal. The link to his thesis: https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/bitstream/handle/10342/8572/W.-Trevor-Freeman-Official-Thesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

I have not seen many references to religious or economic discrimination. In my two studies of NC pensioners (includes the one noted above), it is pretty clear though that pension applicants were at the lower end of the economic strata of American society at time. From my analysis, free people of color were even less well off at they owned less land and were less literate than white pensioners.

Thanks, Matt. I’ve seen zero indications of any sort of racial or religious discrimination. On the other hand, economic discrimination is the very foundation of the pension program. Applicants had to show that they are “in reduced circumstances and stand in need of the assistance of their country for support” … or words to that effect.

Thank you for the background story on this! My husband’s ancestor was one such veteran and we found his widow’s application online a few years ago. The narrative is a delightful read, and gave us a glimpse into the lives of our founding family’s life story during those historic times.

Thank you for an informative and well-written article. I’ve looked at numerous pension affidavits and I now have a better understanding of what drove the waves of applications in 1818 and 1832. Do you believe the rules regarding service length, in addition to memory issues, may have influenced some veterans’ description of their dates of enlistment and discharge?

I suspect the vast majortiy of differences in service dates between governmental records and veterans’ accounts came from foggy memories. These guys are trying to recall events from forty or fifty or more years ago. Not only has a lot of time passed, but most are no longer young minds–they are ones suffering the effects of old age. If you are old enough, think back to events in your life that happened a half-century ago–try to recall the months in which they happened. There are countless examples in the applications of veterans struggling to give an accurate account but their memory simply is not up to the task.

That is not to say nobody tried to lie their way through the process but they are a minority. Far more applicants shunted their own holdings off to their kids in order to qualify for the needs requirement. Pension administrators had a much more challenging time dealing with that activity.