From 1765 to 1766, botanist John Bartram explored Florida, the new southern territory Britain acquired after the Seven Years’ War. William Bartram, his son, accompanied him on that expedition. Named King George III’s Royal Botanist and granted a £50 a year salary, John collected plants he shipped to Europe.[1] In late 1765, John found himself in British East Florida. While on the St. Johns River he made the following notes: “I observed very large oaks, magnolias, liquidamber, near 100 foot high, and guilandina thirty. These grew on a high bluff eight or ten foot above the surface of the river, which rises here eighteen inches at high water, and in dry season is sometimes brackish.”[2]

While traveling with his father, William fell in love with Florida. His infatuation with that place caused him to later try, unsuccessfully, to establish an indigo plantation on the banks of the St. Johns River.[3] William returned to East Florida in 1774 after he secured funding for a second Florida expedition. From 1773 to 1777, William explored the American South, documenting his observations in great detail. An account of his travels, titled Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Choctaws, was published in 1791. Bartram’s observations about the American South provide insight into what that region looked like during the eighteenth century. They also shed light on Native American culture in pre-Revolutionary North America. William’s book, or Travels as it is commonly referred to today, is credited with influencing English Romanticism.

Today, William Bartram’s legacy lives on thanks, in large part, to the efforts of the Bartram Trail Conference. Established in 1976, the Bartram Trail Conference has located and marked Bartram’s route through eight southern states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Highway markers have been established along Bartram’s route, highlighting significant natural or cultural areas the explorer visited all those years ago. Bartram’s steps from Amelia Island to the St. Johns River were a small segment of his journey in Northeast Florida, but a significant one nonetheless, especially when considering that region’s relevance to the Revolutionary War. Indeed, for a time, the space between the St. Johns and St. Marys Rivers was the proverbial “no man’s land” between British-held East Florida and rebellious Georgia. It was the site of raids and counter-raids. At one point, Georgian raiders destroyed all loyalist settlements in that region. Bartram’s account provides modern Revolutionary War scholars with a glimpse into what Northeast Florida’s natural environment looked like during the 1770s.[4]

William Bartram’s direct connection to the American Revolution is minor at best. Bartram avoided any mention of the war or wartime activities in Travels—though it has been said the reason for this omission was probably because Bartram’s southern expedition was financed by British patrons, making the explorer hesitant to mention the war in his account. Bartram nonetheless engaged in the Revolutionary War on the southern frontier when he witnessed a rebel force repel a supposed British invasion from East Florida.[5] Some scholars believe Bartram volunteered as a scout and spy for the Georgians on the East Florida-Georgia border during that time.[6] He was even offered a lieutenant’s commission on the condition that he remain in Georgia. The explorer, however, refused this promotion.[7] He hated war. According to American naturalist Francis Harper, Bartram was an advocate of peace. In Bartram’s own words, “[I] consequently am against War and violence, in any form or maner whatever.”[8] Knowledge of Bartram’s interactions with the rebels, in spite of his convictions, is not surprising; he was close friends with two significant patriots: Lachlan McIntosh and Henry Laurens.[9]

Amelia Island

where the Patriot patrol was shot at by Loyalists. (Author)

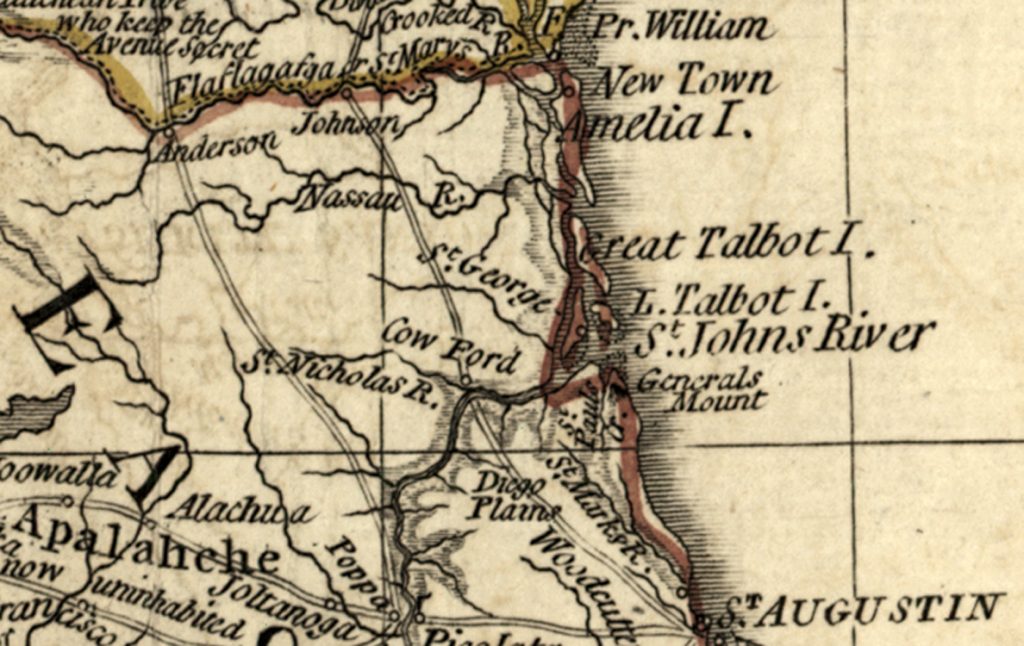

In the spring of 1774, William Bartram landed on the north end of Amelia Island. Making his way to Lord Egmont’s plantation, now the site of modern-day Fernandina, Bartram passed through a forest of “Live Oaks and Palms.”[10] Stephen Egan, Lord Egmont’s agent in East Florida, received Bartram hospitably. During his visit, Bartram beheld a prosperous indigo plantation. An experienced planter, Egan proved to be a good fit for the tasks expected of him on the Florida frontier. With Egan serving as his knowledgeable guide, Bartram toured the island on horseback. He jotted down what he saw in his journal. “Great part of this island consists of excellent hommocky land, which is the soil this plant [indigo] delights in, as well as cotton, corn, batatas, and almost every other esculent vegetable . . . it is a very fertile island.”[11] In addition to the land, Bartram observed several Indian mounds made up of heaps of earth and shell that entombed the bones of the dead. During the Revolutionary War, a Georgian expedition in 1777 invaded East Florida. In May, Col. Samuel Elbert landed on the north end of Amelia Island, near Fernandina. A patrol was sent to scout the south end of the island and to avert any British advance that way. The patrol was ambushed by armed loyalists, and a rebel officer was killed in the ensuing action. Angered over the loss of his officer, Elbert burned every structure on the island and slaughtered all the livestock to prevent the British from using them.[12]

Intracoastal Waterway

After Bartram was well familiarized with Amelia Island, he headed south on the Intracoastal Waterway. Mr. Egan accompanied him since the planter had important business to conduct in St. Augustine, East Florida’s capital. On this leg of the naturalist’s journey, Bartram sailed on Egan’s “handsome pleasure-boat,” manned by four enslaved African Americans. Of this region, between Amelia Island and the St. Johns River, Bartram wrote of the “low salt marshes,” “reedy and grassy islands,” and the presence of rivers that “afford an extensive and secure inland navigation for most craft, such as large schooners, sloops, pettiaugers, boats, and canoes.”[13] When they reached Fort George’s sound, present-day Nassau Sound, Egan shot a pelican that was fishing and took it into the boat. That evening the party camped on the north end of Talbot Island, although they may have possibly camped on Black Hammock Island, located on the west side of Sawpit Creek. Pitching their tents under a forest of “Live Oaks, Palms, and Sweet Bays,” the party enjoyed a dinner of sea fowl that included curlews, willets, snipes, and sand birds. The birds were dressed and seasoned with oysters that laid in heaps in the water near their campsite. After dinner, the party found relaxation hard to come by. Mosquito bites, roaring crocodiles, and the noise emitted from thousands of sea fowls that entirely covered the trees in such “incredible numbers,” made for an eventful evening that robbed the adventurers of any quiet.[14] During the 1777 American invasion of East Florida, Colonel’s Samuel Elbert and John Baker agreed to rendezvous at Sawpit Bluff on Black Hammock Island, eight miles north of the St. Johns River. Colonel Baker and his force reached Sawpit Bluff at the agreed upon time, but Colonel Elbert and his men were nowhere to be found. After waiting several days, a party of Indians stole forty horses from the American camp at Sawpit Bluff. The rebels engaged the Indians in a battle that wounded two of Baker’s men. The horses were recovered, and one Indian was killed.[15]

St. Johns River

According to Bartram, he arrived at Cowford, the site of present-day Jacksonville, three days after he left Amelia Island. In his time, a public ferry provided transport for travelers across the river. Here he purchased a small sailboat for three guineas from a nearby indigo plantation. Bartram bid farewell to Egan and the two men went their separate ways. The naturalist, now alone, proceeded up the St. Johns River. He had with him fishing tackle, a gun, fuse, powder, and shot.[16] The further he sped away from Cowford, the distance between him and any Northeast Florida Revolutionary War activity increased. Throughout the war, the St. Johns River served as a natural barrier that protected St. Augustine from rebel attack. British forces fortified the eastern/southern banks of the river. Regulars of the 60th Regiment were stationed at Cowford.[17] In 1777, a naval battle between the British vessel Rebecca and a sixteen-gun rebel brigantine occurred at the mouth of the river.[18] If it were not for the tactical advantages the St. Johns River provided the British, rebel raiders would have had an easier time penetrating deeper into East Florida.

On July 4, 1818, William Bartram wrote the following excerpt in his diary: “Rejoicing, being anvesery of the Independence of the U. States of N. America.”[19] Francis Harper claims the spirit of 1776 must have stirred within Bartram, motivating him enough to write the above statement. After his travels, Bartram lived out the rest of his life in Philadelphia. He died in 1823 at the age of eighty-four. Despite Bartram’s proximity to Revolutionary War happenings, nothing from the conflict made it into Travels. Edward Cashin believes that the conflict’s omission from Travels was deliberate, the product of Bartram’s idealism. While the new nation defined itself in the wake of the American Revolution, Bartram sought to portray the United States as a garden of Eden, where its people lived together in peace, in an America that was a great and favored nation.[20] When Bartram travelled through Northeast Florida in 1774, he walked the land that would, in two short years, become a battleground.

William’s observations provide a glimpse into a much wilder Florida than we know today. Luckily some of that wilderness has been preserved. What remains, however, is only a fraction of what once was. Crocodiles are virtually nonexistent in Northeast Florida. Birds certainly exist there, but nowhere near the quantities Bartram described. Oysters, for the most part, are no longer safe to eat from the rivers; pollution has rendered them inedible for most of the year. Differences aside, some parts of Northeast Florida still offer visitors a peek into the natural world Bartram encountered all those years ago. The marshes, rivers, and islands within the Timucuan Preserve are still much the same as they were in 1774.

[1]For more on John Bartram see Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, The Life and Travels of John Bartram: From Lake Ontario to the River St. John (Tallahassee: University Presses of Florida, 1982).

[2]Helen Gere Cruickshank, John and William Bartram’s America: Selections from the Writings of the Philadelphia Naturalists (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1957), 54.

[3]Daniel L. Schafer, William Bartram and the Ghost Plantations of British East Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010), 29-38.

[4]William’s observations of Northeast Florida in Travels should be taken with a grain of salt. Historian Daniel L. Schafer believes that William did not accurately depict East Florida’s state of development in the 1770s. Schafer points out that when Bartram passed through East Florida in the 1770s, there were more settlements along the banks of the St. Johns River than Travels led readers to believe.

[5]Edward J. Cashin, William Bartram and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 229.

[6]Francis Harper, “William Bartram and the American Revolution,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 97, no. 5 (Oct. 1953): 573-574; Cashin, William Bartram and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier, 229-234; Martha Condray Searcy, The Georgia-Florida Contest in the American Revolution, 1776-1778 (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1985), 211n96.

[7]Cashin, William Bartram and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier, 233.

[8]Harper, “William Bartram and the American Revolution,” 571.

[9]Cashin, William Bartram and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier, 216-217.

[10]Francis Harper, ed., Travels of William Bartram: Naturalist’s Edition (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1998), 42.

[11]Harper, ed., Travels of William Bartram, 42-43.

[12]Burton Barrs, East Florida in the American Revolution (Jacksonville: The Cooper Press, 1949), 18-20.

[13]Harper, ed., Travels of William Bartram, 44-45.

[15]Barrs, East Florida in the American Revolution, 18-20.

[16]Harper, ed., Travels of William Bartram, 47-49.

[17]Pleasant Daniel Gold, History of Duval County Including Early History of East Florida (St. Augustine: The Record Company, 1929), 58.

[18]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, June 16, 1777, in K. G. Davies, Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783, (Shannon: Irish University Press, 1972-1981), 14:116-118.

[19]Harper, “William Bartram and the American Revolution,” 577.

[20]Cashin, William Bartram and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier, 3-4.

4 Comments

THANK YOU SO MUCH – FOR MAKING ALL OF THIS INFORMATION ABOUT ‘THE REVOLUTION’ EASY

TO READ. EASY TO UNDERSTAND. AND EASY TO LOOK ROWARD TO EACH WEEK.

TO MY KNOWLEDGE – (B.1935) THERE HAS NEVER – EVER – BEEN A PLACE HERE IN PHILADELPHIA

WHERE THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IS PRESENTED IN A WAY THAT IS EASY TO READ. EASY TO

UNDERSTAND. AND EASY TO REMEMBER. AND CERTAINLY – WONDERFUL TO VISIT IN PERSON!!!

THE CREDIT FOR THIS IS OBVIOUSLY DUE – TO YOUR PROFESSONAL STAFF…. TO WHICH I HAVE TO SAY – “THANK YOU VERY MUCH”.. RESPECTFULLY – HENRY T. PAISTE, III

LIVE MEMBER – PHILA. SONS OF THE REVOLUTION – (SR).

Respectfully

HENRY PAISTE 6/1/21 (MONDAY) @ 3:40 PM

Gators abound and oysters are plenty at this time for those who spend time on the NE FL coast, but one can see where the environment is being pressured by development. The only impediment to outright degradation are sand gnats.

Hi Keith,

I live right on the Timucuan Preserve here in NE FL and gators, and edible oysters especially, most certainly do not “abound” around these parts. I have lived here for four years now and have yet to see a wild gator – and I hike a lot. Certainly, gators may exist and this article does not rule that out. But “abound” is not the appropriate word to describe their population here in NE FL, especially in and around the area this article talks about (the Timucuan Preserve).

-George

Loved the article. I got a first edition of Bartram’s Travels and just finished reading it. One question: he references Talahafochte. Do you know where this was? Also, how far in west Florida did Bartram go?

Thanks.