In early May 1775, with the Revolutionary War not even one month old, western Massachusetts Patriot leaders and their Stockbridge Indian neighbors developed a plan to use diplomacy to neutralize a looming danger in the north. Stockbridge ambassadors would take a peace message from their community to the New England colonists’ traditional Native enemies in Canada. The Indian delegation’s resultant mission promoted this objective but also inadvertently sparked a diplomatic incident that further helped the American cause.

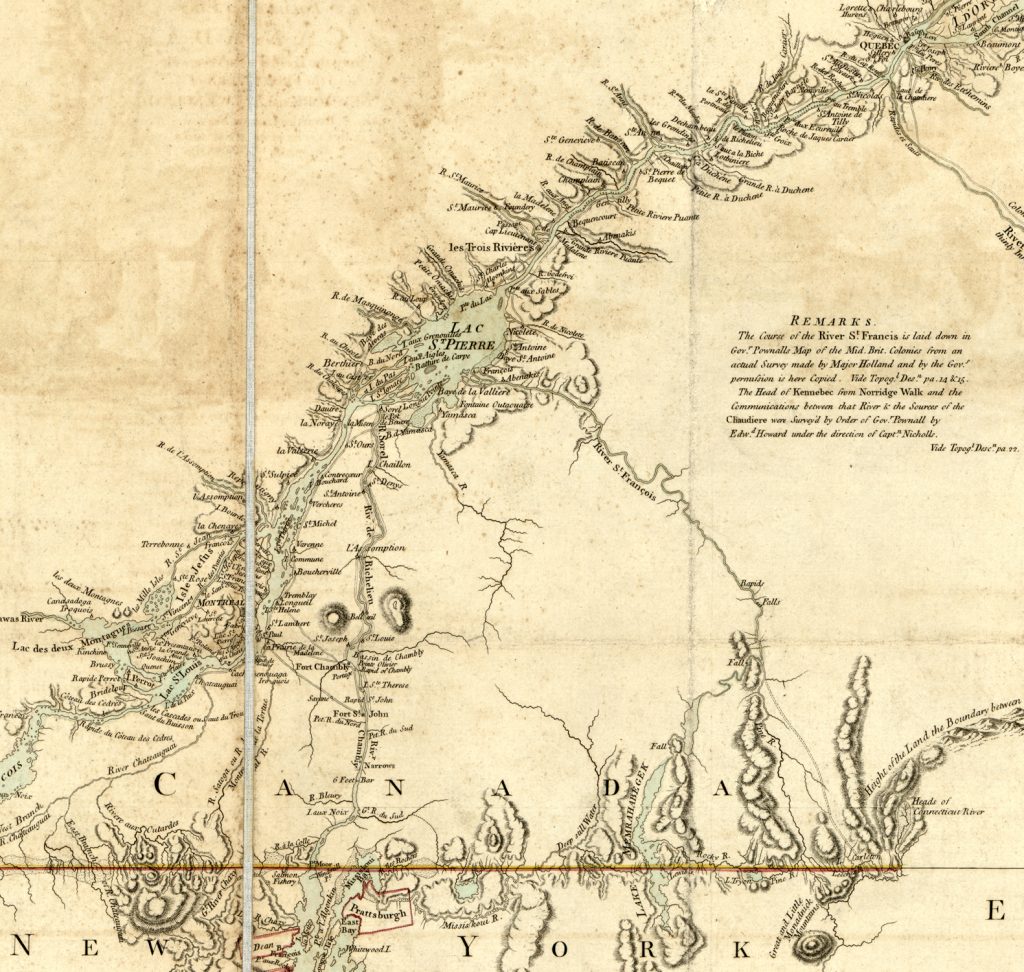

The primary target for this outreach was the Mohawk village-nation of Kahnawake (historically spelled in variations of “Caughnawaga”), southwest of Montreal. Kahnawake was the central council fire of the Seven Nations Indian confederation, composed of Catholic mission villages in the St. Lawrence valley. For almost one hundred years, warriors from these villages had episodically raided New England and New York frontier communities, often as part of the British-French colonial wars—killing settlers, taking captives and plunder, and devastating entire villages. They were a legendary terror for the colonists. While Kahnawake and other Seven Nations Indians villages considered themselves to be independent, sovereign enclaves within the British Province of Quebec, they generally kept good relations and frequently allied with their Canadian neighbors’ imperial government. So, with Revolutionary War hostilities commencing, northern colonies believed new frontier attacks could be imminent if these Indians allied themselves with the king.

American Patriots had their own Indian partners to turn to, the foremost of which were a composite people identified at the time as the Muhheconneock—Mohicans/Mahicans, Wappingers, and Housatonics. Those Indians’ largest settlement was in the western Massachusetts town of Stockbridge, a community founded in the 1730s as a multi-tribal Protestant Indian mission. In the French and Indian War, many Stockbridge Indian men had demonstrated marked commitment to their colonial neighbors by fighting on the British side, most famously in Rogers’ Rangers. After that war, settlers quickly encroached on Stockbridge, displacing many original Native inhabitants. By 1774, the town had become a hybrid community, dominated by Massachusetts colonists who outnumbered the 200 remaining “praying Indians” five-to-one.[1]

Despite the settlers’ impositions, the Stockbridge Muhheconneocks remained strong allies to their American neighbors. On April 1, 1775, even before hostilities commenced at Lexington and Concord, they proclaimed a “firm and steady attachment to the [Patriot] cause.” Muhheconneock captains led warrior detachments in the local minute men and informed the Massachusetts Provincial Council that “the natives of Stockbridge, are ready and willing to take up the Hatchet in the cause of liberty and their country.”[2]

The Stockbridge Muhheconneocks also offered to apply their substantial diplomatic influence with diverse Indian nations including the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Six Nations confederacy, the Ohio Valley Shawnees, and the Seven Nations of Canada. With the situation ripe for war in early April, Muhheconneock Capt. Solomon Uhhaunauwaunmut visited Six Nations Mohawk chiefs to “know how they stand,” and if needed, to offer persuasive pro-Patriot messages. By May 9, he returned with largely encouraging news—at least according to the chiefs he met, the Iroquois Six Nations were not inclined to fight alongside the British and viewed the Americans favorably.[3]

Just days later, the people of Stockbridge got wind of plans to take British-held Fort Ticonderoga at the south end of Lake Champlain. Muhheconneock Indians and their colonial neighbors were concerned that the Kahnawakes in Canada might be alarmed by this armed Patriot intrusion into the periphery of their home region. Stockbridge leaders, including Timothy Edwards (soon to be a Massachusetts congressman and Continental Indian Department commissioner) and village missionary John Sergeant, Jr., worked with Stockbridge chiefs to send ambassadors north to “find out the temper of the Canada Indians,” and use their influence to sway the Kahnawakes and Seven Nations confederates into neutrality.[4]

The Stockbridge chiefs composed a speech that opened with a traditional invocation to council and then described the new war from their perspective: “One Morning I got up, I heard from Boston that the Regulars came out against our People, and there was a great deal of Blood shed,” and “Very soon after this I heard from Boston again, that our People sent some Men up North to Ticonderoga to take Possession of them Forts.” In figurative language, they explained that their white “Brother” only seized Ticonderoga and Crown Point to “guard himself against his Enemies”; the Kahnawakes need not fear attack and were reassured that the Americans had “no evil design against you.” The Muhheconneocks’ speech then suggested that they and the Seven Nations people should “sit down, and smoak our Pipes, under the Shade of our great Tree and have our Ears open and see [watch] our Brethren fight” and advised “let us keep our Convenant Strong[,] do not let any one break that which we made at the End of the War, that we never would fight against one another again.” Captain Abraham Nimham and two other unidentified Stockbridge Indians were selected to travel to the Kahnawake council fire to deliver this speech with the requisite wampum belts for a formal diplomatic overture.[5]

Before Nimham and his compatriots reached Fort Ticonderoga, on or before May 20, they learned that the post and nearby Crown Point had been taken by Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, various Connecticut and western Massachusetts men, and nominal co-commander Col. Benedict Arnold. Allen and Arnold proved unable to get along, so after arrival the Stockbridges conferred separately with the two Patriot leaders. They first talked with Arnold, who encouraged their peace mission. He wrote Nimham a letter of introduction to Canadian Patriot leader Thomas Walker, saying “any Assistance and Advice you are kind enough to give him will be gratefully acknowledged.” Arnold also arranged for Patriot interpreter Winthrop Hoit to join the Stockbridge travelers. Hoit was a valuable borderlands agent, a repatriated Kahnawake captive who had been adopted into the community for four years during the French and Indian War and was conversant in Mohawk. Hoit had also visited the village just a few weeks earlier in a pre-hostilities intelligence-gathering trip.[6]

Four days later, they conferred with Ethan Allen at Crown Point. Taking advantage of the Stockbridge ambassadors’ trip into Canada, Allen wrote a letter for them to deliver to what he called “the four Tribes”: Seven Nations confederacy members in Kahnawake, Kanesatake, and Odanak (St. Francis), and somewhat arbitrarily, he included the Oswegatchies, a small community with only ill-defined confederacy ties. Allen’s letter recounted British fault in starting the war and detailed recent American military successes. The Green Mountain Boys leader also shared his desire that the Indians in Canada would “not fight for King George against your friends in America.” To this point, his letter conformed with the Stockbridges’ mission objectives and other Continental leaders’ strategic intent. Trouble came from what followed.[7]

Allen then boasted, “I was always a friend to Indians, and have hunted with them many times, and know how to shoot and ambush like Indians, and am a great hunter,” and declared “I want to have your warriours come and see me, and help me fight the King’s Regular Troops.” The rest of this plea is oft quoted: “You know they stand all along close together, rank and file, and my men fight so as Indians do, and I want your warriours to join with me and my warriours, like brothers, and ambush the Regulars.” In return, he promised “money, blankets, tomahawks, knives, paint, and any thing that there is in the army.” His invitation for the Canada Indians to take up arms on the American side was a wholesale break from the Stockbridges’ mission for simple Kahnawake neutrality.[8]

Historians have frequently misinterpreted Allen’s letter as evidence that he launched the Stockbridges’ outreach to Canada, and that the principal objective therefore was to recruit Indian warrior allies. Instead, Allen appears to have taken advantage of his position as the last American leader meeting with the Muhheconneock delegation to promote his own agenda—hoping to gather Indian allies for an invasion of Canada that he soon began pitching in earnest to Patriot leaders. It is not even clear whether Nimham and his fellow ambassadors actually knew what Allen’s letter said. Regardless, they agreed to carry it into Canada.[9]

Four Kahnawakes visiting Crown Point at the time offered to serve as guides, and in the next day or two they cruised north on Lake Champlain with the Stockbridges and Winthrop Hoit, entering Canada on the Richelieu River. The Indian escorts planned to land at Fort St. Johns, the first settlement on the other side of the border, where their Stockbridge guests could rest while they sent to Kahnawake for horses to ease the last thirty miles of the party’s journey. Fort St. Johns, however, had only been recently reinforced by scores of British regular soldiers and Canadian Loyalists after Arnold, and then Allen, separately raided the post on May 18. Interpreter Winthrop Hoit thought that stopping at the fort was a bad idea, “fearful of being taken prisoner,” so the party dropped him ashore upriver from the post, and he ventured through the woods to Kahnawake on his own. Then, just as Hoit predicted, the entire complexion of the diplomatic mission changed in a flash at Fort St. Johns.[10]

The Fort St. Johns garrison was on high alert with frequent reports of rebel American scouts probing the provincial border. So, when the Stockbridge strangers arrived, British regulars detained them long enough to inspect their packs, discovering the wampum, and more importantly, the telltale correspondence from Arnold and Allen. The redcoats justifiably interpreted the latter document as evidence that the Muhheconneocks came to Canada with hostile intent. The soldiers released the Indians for the moment and waited to act on their discovery.[11]

That evening, while the Stockbridges sojourned, British soldiers “decoyed” them “to the Waterside when they bound them tight with Cords laid them in the Battoe on their backs tied their Legs to the Top of the Battoe, leaving them in that Condition all Night.” At dawn’s light, the redcoats expeditiously and roughly transported the three Indian ambassadors a dozen miles down the Richelieu River to the more secure British post at Fort Chambly. There, Abraham Nimham successfully begged to be taken to Montreal, where authorities could straighten out the situation—presumably with the expectation that he and his companions would be released as Indian ambassadors, who were traditionally given free passage under Native protocols, even if coming from enemy nations.[12]

As Abraham Nimham recounted, when soldiers delivered the Stockbridge ambassadors to Montreal, the “Commanding Officer ordered them untied and gave them refreshment”—seemingly a positive sign. However, British officers privately held a court martial to weigh the evidence and judge the Stockbridge ambassadors, allegedly determining that the Indians should be hanged, since they had been “sent to engage the Indians to fall upon the regulars.” These were tense days in Canada, and Gov. Guy Carleton and his military officers were realistically concerned about rebel American spies, incursions, and even a potential invasion.[13]

Unfortunately for the historical record, Nimham did not identify the “commanding officer” by name. Carleton (who was also the commanding general in Canada) had recently moved his headquarters to Montreal but given his consistently delicate handling of the Seven Nations and other Indians, it seems unlikely that he would have been directly involved in the court martial and insults that followed. The “commanding officer” in Nimham’s account was probably Lieut. Col. Dudley Templer, the senior field officer at Montreal; yet it also seems peculiar that if Carleton truly was in the city that day, that he would have been completely oblivious and uninvolved in the incident—perhaps he was away.

While the British court martial took place, Kahnawake leaders got word of the Stockbridge ambassadors’ abduction and rushed the ten miles downriver from their village to Montreal. About twenty Kahnawake “Chiefs and Warriors” arrived, first seeking to comfort the distraught Muhheconneocks who had since been warned that their lives were at risk. A sachem—one of Kahnawake village’s hereditary clan leaders—told Nimham, “Brother I hear you are agoing to be hanged, if that be so, I am come to take your place[,] I shan’t suffer such a thing to happen to my Brother in my Country.” The sachem then turned to the “Commanding Officer” and said “I am come for my Brother, what be you agoing to do with him.” The officer replied that “he was agoing to do with them as he pleased, they were his Prisoners,” which sounds more like the characteristically high-handed tone of many British army officers than a senior government official—Templer rather than Carleton[14]

The Kahnawake sachem was offended by the disrespectful remark, and tried to make an analogy about diplomatic principles, presumably lost on the commander who next demanded that the Stockbridges speak the message conveyed in their wampum belts. Abraham Nimham complied, but later confessed that “he left out a Part.” The British officers were still unhappy. Then a French Canadian entered the scene and threw fuel on the fire by saying “he came from New York and reported that there had been a great fight there. Many Regulars were killed, and that there were Indians there fighting &c. He supposed that these Indians were sent by the Grand Congress to hire the Canadian Indians to fall upon the Regulars and kill them all.” The redcoats promptly renewed their threat to hang the Stockbridge ambassadors.[15]

The Kahnawake party was insulted by the British officers’ haughty, imperious attitude and “High threatening words passed between the General [sic] and the Indian Sachems.” British officers said “they did not care the Snap of their Finger for all the Indians, they were not of much Importance[,] they would hang them all if they had a mind for it.” The Kahnawake sachem offered this bold retort:

you say I am little, you don’t care the Snap of your finger for me, now I say the same to you, I don’t care the Snap of my Finger for you, you call me little, it will take me a Year to go and call all my Friends together, if you think it is for your good hang them, but remember I shant forget it, You have tryed to hire me to fight for you but I love peace, and did not want to meddle with your Quarrel, I have not known yet who was my Enemy, who I ought to fight, but now I shall know who is my Enemy, who is a going to hurt me.[16]

Given the sachem’s firm counter-threat with its strategic implications, the redcoat officers finally reconsidered and deemed it best to let the three Stockbridges go. They told the Kahnawakes “to take their Brothers and be gone, and if they ever came that way again, they would hang them [the ambassadors] without asking any Questions and gave them but four days to get out of their Territories.” The Indians went to Kahnawake, where Nimham and his companions finally delivered their message and wampum to the council. In return, the Muhheconneocks accepted a formal reply from their hosts to deliver back to Stockbridge. Nimham and his partners departed Canada soon thereafter with five Kahnawake escorts.[17]

Reaching Crown Point by June 10, the Stockbridge ambassadors and Kahnawake escorts first met with Ethan Allen and officers in his circle. The Indians assured them that the Kahnawake people understood the war “to be a family dispute,” and that they would “meddle in no way.” Nimham also showed “the marks of abuse” he had suffered at British hands. Allen and the others recognized the Indians’ sacrifice and service to the cause by contributing “a Present … Largely, out of their own Pockets” to the Stockbridges and Kahnawakes involved. Interpreter Winthrop Hoit and the Indians also met with Colonel Arnold on or before June 13, and the Kahnawakes provided additional information that their nation encouraged the American “Army to march into Canada, being much disgusted with the Regulars.”[18]

From Crown Point, Nimham and his companions bore the formal Kahnawake response back home to Stockbridge, arriving on June 15. Delivering a proxy speech and wampum, Nimham first conveyed the Kahnawakes’ apology for British abuse of the ambassadors, saying that they “wipe the Tears from your Eyes, that comes from the Trouble that has happened to your Young Men.” After that formality, the Canada Indians declared their agreement with the key points of the Muhheconneocks’ outreach. They promised to keep “the road,” or flow of communications, open between them, and would remember “the agreement of friendship, that our fathers have made—Let us hold that fast—Let no one break that, so as to divide us.” Finally, and most importantly for the Americans, the Kahnawakes proclaimed, “there is seven Brothers of us (meaning seven Tribes) we are all agreed in this—Now we say to you—I would have you sit still too, and have nothing to do with this quarrel; but be strong in your hearts, and we intend to do the same.” At face value, the Muhheconneocks appeared to have secured a tremendously important promise of Seven Nations confederacy neutrality.[19]

Missionary John Sergeant and the Stockbridge town committee were encouraged by the party’s results and asked the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to compensate Nimham for his losses and suffering; he soon received thirty-six shillings. Town leaders also sent transcripts of the Muhheconneock and Kahnawake speeches to the Continental Congress and Albany Committee of Correspondence. In a letter probably enclosed with the messages delivered to Philadelphia, a gentleman at Stockbridge—presumably Sergeant or Timothy Edwards—wrote: “This event turned much to our advantage, and has fully fixed the minds of the [Seven Nations] Indians there against the regulars,” and that “The Canadian Indians farther [sic] told our Indians, That if they did fight at all, they would Fight Against the Regulars, for they did not like them.”[20]

This information reached Congress on June 29, a particularly important time for assessing the threat from Canada. Just three days earlier, Congressional delegates had been alarmed by an apparently reliable report from the Albany Committee of Correspondence that “the French Caughnuago Indians had taken up the Hatchet” to serve with Governor Carleton and the British. That account, in turn, had prompted Congress to grant Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler authority to invade Canada “and pursue any other measures . . . which may have a tendency to promote the peace and security of these Colonies” there. The Muhheconneocks’ new information, direct from Kahnawake, served to deflate fears of imminent Indian attack on the northern frontier. Yet these two seemingly contradictory reports—from Albany and Stockbridge—are characteristic of the confusing intelligence from Canada that came throughout the summer of 1775.[21]

In reality, the Kahnawake nation would not choose sides for most of that year. Governor Carleton and his agents drew coerced promises from the village council to defend Canada if attacked, but actual Kahnawake contributions remained minimal. At the village and Seven Nations confederacy levels, they generally held to their own version of neutrality during the 1775-1776 invasion and occupation of Canada, but individual chiefs and warriors were not restrained from taking sides. The situation remained tense, confusing, and complex as different Kahnawake and Seven Nations factions cooperated with and fought alongside the Americans and the British.[22]

The actual impact of the Stockbridge diplomatic overture in May and June 1775 is impossible to assess in isolation, particularly since its message conformed with Kahnawake village and confederacy predispositions. However, the redcoats’ mistreatment of the three Muhheconneock Indian ambassadors undoubtedly served to push Seven Nations fence-sitters away from the king and to encourage Kahnawake village’s substantial anti-British/pro-American faction. That abusive episode in Montreal also had direct influence on at least one future Native diplomatic episode.

In the critical first weeks of the American invasion of Canada, an Oneida delegation visited Kahnawake just as many Seven Nations chiefs and warriors appeared ready to throw their support to the British. The Oneidas delivered a message, ostensibly from the Six Nations confederacy, promoting full neutrality for the Canada Indians. In an attempt to blunt the impact of the Oneidas’ message, British officials invited them to visit Montreal for talks. The Kahnawakes, however, warned the Indian diplomats not to go, “lest they should be served like the Stockbridge Indians, and be made prisoners.” As a result, the Oneidas declined the invitation, stayed at the council-fire village, and successfully persuaded the Seven Nations to maintain neutrality—thereby precluding most confederacy members’ direct participation in the fighting that fall when the American invasion was quite precarious. So, while Abraham Nimham’s mission to Kahnawake may not have had decisive effect on its own, it undoubtedly nurtured diplomatic relations between two key northern Indian nations that were inclined towards the Americans. Perhaps more significantly, the Montreal incident fueled Indian factions’ anti-British sentiments, favoring a confederacy-level neutrality and indirectly limiting the scope and scale of Seven Nations involvement as the Revolutionary War continued to grow.[23]

[1]Letter from Thomas Cushing, August n.d., 1776, i78, r93, v5 p57-58, M247 Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995),90-91. The spelling “Muhheconneock” is taken from Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, “Our History,” https://www.mohican.com/origin-early-history/. See also Patrick Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992) and David J. Silverman, Red Brethren: The Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians and the Problem of Race in Early America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010).

[2]April 1, 1775, Massachusetts Provincial Congress, and same to Johoiakin Mtohskin, April 1, 1775, Peter Force, ed. American Archives. 4th [AA4] and 5th [AA5] Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837–53), AA41: 1347.

[3]Speech delivered by Capt. Solomon Uhhaunauwaunmut for Massachusetts Provincial Congress, April 11, 1775, AA4 2: 315-16; Petition and Memorial of John Sergeant, Missionary to the Mohekunnuk [sic] Tribe of Indians at Stockbridge, (read November 27, 1776), AA5 3: 868-69; A Gentleman at Pittsfield to an Officer in Cambridge, May 9, 1775, AA43:546; Letter from Thomas Cushing, August n.d., 1776, i78, r93, v5 p57-58, M247, NARA. There was no clear political consensus in the Mohawk nation or Haudenosaunee confederation in 1775 or at any point in the war.

[4]Petition and Memorial of John Sergeant, (read November 27, 1776), AA5 3: 868-69; Elisha Phelps to the Connecticut General Assembly, May 16, 1775, Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society 1 (1860): 176; Stockbridge Indians to the Caghnawagas, May 13, 1775, James Sullivan, ed., Minutes of the Albany Committee of Correspondence, 1775-1778, volume 1 (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1923), 129-30.

[5]Stockbridge Indians to the Caghnawagas, May 13, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 129-30.

[6]Benedict Arnold to Thomas Walker, May 20, 1775, fol. 148, Colonial Office [CO] 42/34, Library and Archives Canada; Arnold to Jonathan Trumbull, June 13, 1775, AA4 2: 977; “Benedict Arnold’s Regimental Memorandum Book,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 8 (1884): 371-72; Ethan Allen to New York Congress, June 2, 1775, AA42: 892; John Brown to Committee of Correspondence in Boston, March 29, 1775, AA4 2: 244; David W. Hoyt, Hoyt Family: A Genealogical History of John Hoyt of Salisbury … (Boston: C. Benjamin Richardson, 1857), 51.

[7]Allen to Assembly of Connecticut, May 26, 1775, AA42: 713; Allen to “The Councillers at Koianawago [sic] pr. Favor of Capt. Nimham, CO 42/34 fol. 149-50 [also AA4 2: 714].

[8]Allen to “The Councillers at Koianawago [sic] pr. Favor of Capt. Nimham, CO 42/34 fol. 149-50 [also AA4 2: 714].

[9]Allen to Assembly of Connecticut, May 26, 1775, AA42: 713; Allen to Continental Congress, May 29, 1775, AA42: 733; Allen to New York Congress, June 2, 1775, AA42: 892; Allen to the Massachusetts Congress, June 9, 1775, AA4 2: 939; Barnabas Deane to Silas Deane, June 1, 1775, “Correspondence of Silas Deane,” Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society 2 (1870): 248.

[10]Abraham Nimham’s Relation, July 5, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 131; June 5, 1775, “Arnold’s Regimental Memorandum Book,” 371-72.

[11]Nimham’s Relation, July 5, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 131.

[13]Ibid.; Extract of a Letter from a Gentlemen at Stockbridge to a Gentlemen of the Congress, June 22, 1775, Pennsylvania Ledger (Philadelphia), July 1, 1775 [also AA4 2: 1060-61].

[14]Nimham’s Relation, July 5, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 131-32.

[16]Extract of a Letter from a Gentlemen at Stockbridge …, June 22, 1775, Pennsylvania Ledger, July 1, 1775; Nimham’s Relation, July 5, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 132.

[17]Nimham’s Relation, July 5, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 132; Ethan Allen, Samuel Elmore, etc. to Continental Congress, June 10, 1775, i162, r179, v1, p17, M247, NARA (also AA4 2: 958).

[18]Allen, Elmore, etc. to Continental Congress, June 10, 1775, AA4 2: 958; Arnold to the Continental Congress, June 13, 1775, AA4 2:976; Arnold to Jonathan Trumbull, June 13, 1775, AA42: 977-78.

[19]Answer to a Speech to the Caughnawagas … sent by the Stockbridge Indians, returned June 15, 1775, Pennsylvania Ledger, July 22, 1775 (also AA42: 1002-3).

[20]Massachusetts Provincial Congress, July [3] 1775, AA4 2: 1480; Massachusetts Provincial Congress to the Moheakounuck Tribe of Indians, June 8, 1775, AA42: 1397; July 8, 1775, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 129; Extract of a Letter from a Gentlemen at Stockbridge …, June 22, 1775, Pennsylvania Ledger, July 1, 1775.

[21]Albany Committee to Continental Congress, June 21, 1775, Sullivan, Minutes of the Albany Committee, 1: 94-95; June 26, 27 and 29, 1775, Worthington C. Ford, ed. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789 (Washington, DC, 1904–37), 2: 108-11; Connecticut Delegates to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., June 26, 1775, and John Hancock to George Washington, June 28, 175, Paul H. Smith, et al., eds. Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789, volume 1(Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976), 1: 542-43, 555. The text of the Kahnawake response to Stockbridge was printed in The Pennsylvania Ledger, July 22, 1775.

[22]For additional information on the very complex Seven Nations political scene in 1775, see Mark R. Anderson, Down the Warpath to the Cedars: Indians’ First Battles in the Revolution (Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 2021), chapters 1 through 3.

[23]Report of the Deputies of the Six Nations of their mission to the Caughnawagas, September 24, 1775, AA4 3:798; Anderson, Down the Warpath, 25-27, 155.

3 Comments

This excellent article clarifies the importance and complexity of Stockbridge, Mohawk, and other native involvement in the American Revolution. It also reminds us that much is lost in the simplistic generalities that make up so much of what most people today think they know about the origins of the US. Thanks for writing an article so rich in meaningful detail.

Thanks for clearing up my confusion about Stockbridge and Kahnawakes during events in the summer of 1775. When I wrote “Wooster’s Invisible Enemies” I didn’t quite understand why Stockbridge ambassadors were arrested or why Kahnawakes intervened and rescued them. Mixed messages from patriots account for the arrests and Tribal wampum belts, obviously strong and enduring, explain the rescue. Your article is well-documented, clear and concise.

Excellent article, Mr. Anderson.