“Few people know the predicament we are in,” wrote George Washington, while he expressed the Continental army’s dire circumstances.[1] By January 1776, just six months into the Revolutionary War, the Continental army faced a crisis outside Boston. This particular crisis, not caused by a British attack, was a personnel issue. “Search the volumes of history through,” Washington wrote, “and I much question whether a case similar to ours is to be found . . . to have one army disbanded, and another to raise, within the same distance of a reinforced enemy; it is too much to attempt—what may be the final issue of the last manouvre, time can only tell.”[2] The Continental army, having grown to just over 22,000 soldiers, was about to disperse. Most soldiers’ enlistment contracts expired on January 1, 1776, and less than half agreed to reenlist.[3] Entire regiments were leaving the battlefield, headed for home. Congress had not paid the army for two months in a row.[4] Their short enlistments now at an end, dissatisfied soldiers believed their commitments were done. The American Revolution almost ended before it began, not due to a battlefield defeat, but in large part to the overwhelming personnel challenges inherent in creating and maintaining the first national army.

Historians frequently highlight the tremendous challenges the Continental army endured. The army’s early rabble nature faced many leadership, training, discipline, and logistical weaknesses. One of the most frustrating issues was its specific personnel problems. The army’s manpower shortage, recruitment and reenlistment crises, and financial woes, comprised a unified theme. They all related to the often unglamorous and tedious topic of personnel management, or in modern terms, “human resources.” The army only survived by successfully coping with these challenges through strength reporting that gave it an ability to see itself, improvisation in recruiting and reenlistment to retain its force, and short-term fixes in finances to keep the army together long enough to win the war. Personnel management was a vital factor in the success or failure in the fight for independence, one which, had the Continental army not sufficiently coped with, the American Revolution might have quickly collapsed under British occupation.

Building (and Re-Building) the Army

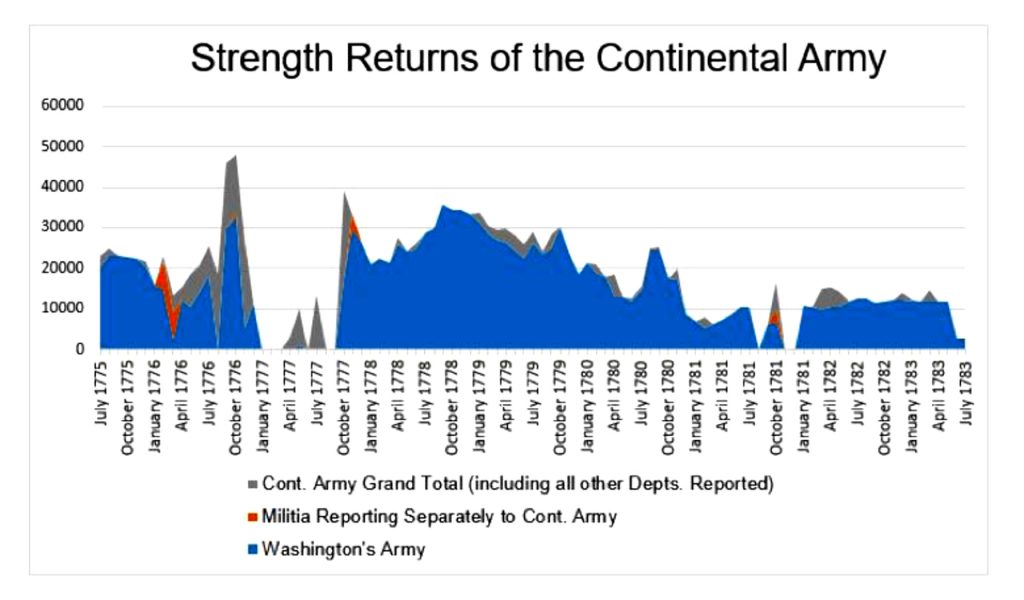

The Continental Congress created a national army with initially modest proportions that reorganized multiple times to cope with personnel challenges. After the first armed conflict occurred at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Congress created the Continental army on June 14, 1775. Starting from scratch, the very first Continental army establishment included only ten regiments, six from Pennsylvania, two from Maryland, and two from Virginia. The Continental army assumed temporary control over the New England militia forces mustering outside Boston and attempted to incorporate them into the army on a formal basis. The total force authorized by Congress in 1775 was 22,000 men, a number which the army exceeded by October 1775.[5]

The Continental army reorganized itself frequently as a coping mechanism to handle its personnel shortfalls. The foremost challenge was expiring enlistments that caused an aggressive personnel turnover. Three major structural overhauls occurred in the winters of 1776, 1777, and 1780, each corresponding with a massive personnel exodus. In January 1776, less than half the army remained in service, and strength fell to under 10,500 soldiers.[6]

The crisis over the army’s possible dissolution in early 1776 repeated itself in the winter of 1777 due to expiring enlistments. Washington implored Congress for assistance: “We are now as it were, upon the eve of another dissolution of our Army—the remembrance of the difficulties which happened upon that occasion last year . . . that unless some speedy and effectual measures are adopted by Congress; our cause will be lost.”[7] Washington further confided to his relative Lund Washington, “Our only dependence now, is upon the Speedy Inlistment of a New Army; if this fails us, I think the game will be pretty well up.”[8] Washington pointed to personnel issues as the root cause: “ten days more will put an end to the existence of our Army . . . It is needless to add, that short inlistments, and a mistaken dependence upon Militia, have been the Origin of all our misfortunes, and the great accumulation of our Debt.”[9]

To cope with the crisis, Congress reorganized the army and changed the standard enlistment from one to three years, or the duration of the war. Congress authorized the “Eighty-eight Battalion Resolve,” the largest reorganization of the war, which occurred in September 1776. This began as an “army on paper” as manning levels fell to their lowest point in the war.[10] The 88 regiments expanded by December to 119 authorized regiments, but few were able to reach their full authorizations. If fully manned in 1777, the Continental army would have been over 90,000 soldiers.[11]

The Continental army never came close to half of its 1777 authorization and struggled to retain personnel throughout its existence. The last major reorganization occurred in 1780, when the three-year enlistments of 1777 expired. Congress, now practically bankrupt, reduced the army’s size to only 49 regiments. After the 1780 reorganization, the army’s quota settled around 35,000 soldiers for the remainder of the war.[12] This aggressive personnel turnover posed a tremendous challenge to the Continental army’s administration. All the more credit was due to the individuals who eventually found solutions to make the system manageable, if not ultimately successful.

Handling Paperwork

With such a constant organizational flux, as well as battlefield losses, casualties, sickness, and desertion, the army was an administrative nightmare. The Continental army turned to the British Army as a model for handling organization and administration. Several Continental officers including Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, and Washington himself had experience serving in the British Army during the French and Indian War. Washington recommended British military manuals to his officers such as Humphrey Bland’s A Treatise of Military Discipline and William Young’s Manoeuvres, or Practical Observations on the Art of War which included detailed descriptions on the specific duties of officers, including administrative tasks and procedures.[13] Despite having a model to follow, administering a newly created national army proved an imposing task. Washington frequently expressed the immense stress he was under, revealing: “At present, my time is so much taken up at my desk, that I am obliged to neglect many other essential parts of my duty: it is absolutely necessary, therefore, for me to have persons that can think for me, as well as execute orders.”[14]

Washington’s aides, whom he referred to as his “family,” were essential in administering the army. Twenty-two aides, including Robert Harrison, Joseph Reed, Tench Tillman, Alexander Hamilton, and John Laurens served Washington during the war. Washington’s writings reveal he placed tremendous value on his military family. For example, he implored Joseph Reed to serve as his personal aide on five different occasions in 1775 and 1776, revealing a dire urgency for administrative help: “Real necessity compels me to ask you whether I may entertain any hopes of your returning to my family?”[15] Reed eventually accepted and served as Washington’s aide, as well as the second adjutant general of the army’s staff in 1776.

Beyond his aides, the Continental army’s staff assisted Washington. The first staff had five positions: adjutant general, commissary of musters, paymaster general, commissary general, and quartermaster general.[16] These positions were responsible for the war’s basic necessities, including tracking the revolving door of personnel and their pay. The staff structure later reorganized to include an inspector general, a position made highly efficient by Baron von Steuben at Valley Forge in 1778.

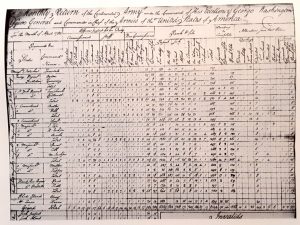

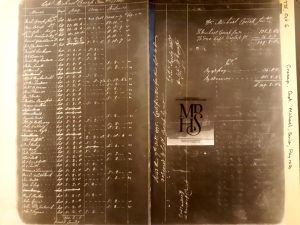

The staff position most associated with personnel was the adjutant general. The Continental army’s first adjutant general, Horatio Gates, joined Washington’s headquarters in July 1775. He relieved Washington of many duties, including publishing the Articles of War and issuing instructions to the recruiting service.[17] The official appointees after Gates were Joseph Reed, Timothy Pickering, Alexander Scammell, and Edward Hand.[18] Timothy Pickering assigned a deputy to each territory’s department to streamline strength reporting. Alexander Scammell further standardized the use of pre-printed forms and issued “blank-books” to every soldier for keeping their personal records.[19] Scammell and Hand collected the army’s strength returns into a master account, one that still exists.[20] Collectively, the adjutants general were responsible for the essential personnel administrative function, strength reporting.

Strength Reporting

Washington’s army was surprisingly efficient at strength reporting that allowed the Continental army to see itself and address personnel shortfalls. Strength reporting was the systematic and routine collection of numerical data that communicated an individual unit’s strength and readiness. Strength returns captured a remarkable amount of data, especially surprising considering everything was calculated by hand. Returns numerically compiled units by regiment and brigade, listed officers by grade, tabulated numbers of rank and file soldiers, listed non-available statuses (sick, furlough, confined, etc.), presented alterations (gains and losses), and even included a “wanting to complete” calculation that gave recruiters their target number to complete their unit’s authorized strength.[21]

Washington relied heavily on these returns for his army’s capabilities and limitations. Washington complained of the tardiness in producing a strength return in January 1776 where he emphasized their importance: “it is impossible that the business of the Army can be conducted with any degree of regularity or propriety,” and threatened to place his subordinate commanders “under arrest and tried for disobedience of Orders” if they did not produce them on time.[22]

Strength reporting was essential in accounting for non-available soldiers and determining unit readiness. Soldiers could be absent for duty for a variety of reasons, most commonly sickness. The strength returns for the army outside Boston in 1775 reported that of 22,676 total, there were 2,500 sick, 750 furloughed, and 2,400 detached on various duties.[23] This was a staggering 24 percent non-available rate, a vital planning consideration for the commander.

Sickness was a constant challenge for the army’s personnel readiness. The army suffered a smallpox outbreak as early as 1775; Washington wrote “The small-pox is in every part of Boston . . . If we escape the small-pox in this camp, and the country round about, it will be miraculous.”[24] The Continental army’s unavailable numbers peaked in 1777, reaching as high as 35 percent unavailable due solely to sickness.[25] This was utterly crippling to the army’s operations and was essential to the commander’s planning. In response to sickness and injuries, the army created the “invalid corps,” a category on strength returns where repurposed wounded soldiers, unfit for future battles, still performed garrison duties.[26]

Strength reporting allowed the army to track its rates of desertion, another crippling personnel issue. Washington complained that the penalty for desertion was too lax, saying “thirty and 40 Soldiers will desert at a time” and even make a game of it.[27] One estimate accounted for 1,134 men deserting from the Continental army between 1777 and 1778 alone. The number of court martial trials for desertion increased from only 19 in 1775, to 142 in 1776, and reached its peak of 157 recorded cases in 1781.[28] Congress raised the penalty for desertion to the death penalty in 1776. At times, units offered amnesty to deserters to recoup their manpower.[29] Despite the penalties, high desertion rates continued to plague the army.

Recruitment and Reenlistment

Tracking the unit’s personnel status was imperative to a functioning army, but not as vital as recruiting these soldiers in the first place. The Continental army faced constant struggles with recruitment and reenlistment shortfalls. Many colonists’ loyalties lay with the militia and independent state regiments, who offered more appealing opportunities than the Continental army in terms of better pay and shorter terms of service. Soldiers’ motivations were another factor evident in recruitment. While patriotic rhetoric of liberty ran high in the first year of the war, it waned as time passed. The Continental army could not rely on patriotic fervor to satisfy its recruitment needs. Commanders and state officials increasingly had to improvise and switch to more coercive methods to man the army.

Recruiting reflected colonial America’s localism. There was no centralized recruitment branch. Congress gave states quotas based on a percentage of their adult male population and it was up to the states to fill them. Recruiters marketed in their home communities to fill their companies. Congress forbade recruiters from crossing state lines, their “respective jurisdiction,” warning that any “officer or officers who may have marched or removed from the State to whose battalions he or they belong” was committing a reportable offense.[30]

Recruiters used enlistment “bounties,” cash bonuses, to attract prospective soldiers. Bounties ranged in amount, and they were a strong motivator for young enlistees. One young soldier, Joseph Plumb Martin, recalled when he was first considering becoming a soldier:

“A dollar deposited upon the drum head was taken by some one as soon as placed there, and the holder’s name taken, and he enrolled . . . My spirits began to revive at the sight of the money offered; the seeds of courage began to sprout . . . O, thought I, if I were but old enough to put myself forward, I would be the possessor of one dollar, the dangers of war notwithstanding.”[31]

To many young prospects, the enlistment bounty may have been the most amount of money they had ever earned in their life. This was a strong incentive for enlisting.

Incentive bounties brought one difficulty: bounty jumping, where a man enlisted into a unit just to collect the bonus and then immediately desert, sometimes repeating the process with other units. This was particularly outrageous to army officers. General orders in 1777 declared: “This offence is of the most enormous and flagrant nature, and not admitting of the least palliation or excuse, whosoever are convicted thereof, and SENTENCED TO DIE, may consider their EXECUTION CERTAIN and INEVITABLE.”[32] To combat the problem, recruiters enforced a color-coded ribbon system for new enlistees to wear on their hats, signifying they had already enlisted. New recruits had to wear the ribbon until the regiment fully assembled and joined the army, or they risked a punishment of “thirty-nine lashes.”[33]

Competition with the localized military organizations detracted from Continental recruiting efforts. Many would-be soldiers, upon hearing rumors of harsh conditions in the Continental army, preferred to join independent state regiments, similar to militia, as well as privateering outfits that paid more and provided shorter enlistment terms. Washington was keenly aware of this problem, commenting: “It is in vain to expect that any (or more than a trifling) part of this Army will again engage in the Service . . . When Men find that their Townsmen & Companions are receiving 20, 30, and more Dollars for a few Months Service” in state militias.[34] Militia and state regiments offered young men with competitive options for enlisting. As Washington observed, motivations for service changed from patriotic fervor to more realistic interests such as pay.

In conjunction with recruiting, reenlistment was among the most challenging personnel issues. The army’s three major personnel crises in 1776, 1777, and 1780 each corresponded directly to expiring enlistment terms. Washington referenced this issue: “Our inlistment goes on slowly by the returns last Monday, only 5,917 men are engaged for the insuing campaign; and yet we are told that we shall get the number wanted as they are only playing off, to see what advantages are to be made, and whether a bounty cannot be extorted either from the publick at large, or Individuals.”[35] Soldiers waited until the last possible moment to reenlist, gaming the system, to see if they could maximize their benefits.

Short enlistments were a root cause of personnel shortages. This was among Washington’s most frequent complaints, as he wrote: “No man dislikes short and temporary enlistments more than I do—No man ever had greater cause to reprobate and even curse the fatal policy of the measure than I have.”[36] At the war’s start, enlistment in the Continental army was for one year, but the diverse state regiments and militias had even shorter enlistment terms. Even one year enlistments were too long for some prospective soldiers, as Joseph Plumb Martin recalled in 1776: “Soldiers were at this time enlisting for a year’s service; I did not like that, it was too long a time for me at the first trial; I wished only to take a priming before I took upon me the whole coat of paint for a soldier.”[37] Martin’s first enlistment was for only six months in a unit he referred to as one of the “new levies.” Martin’s remark likely captured the general thinking of many prospective soldiers. While Martin reenlisted and endured the entire war’s duration, many other soldiers did not.

Washington advocated for both a national draft and for enlistments to last for the war’s full duration on multiple occasions. He wrote, “nothing is now left for it but annual and systematical mode of drafting . . . I see no other substitute.”[38] Congress did not attempt to implement a national draft; they left that decision up to the states. In the winter of 1777, Congress successfully extended a standard Continental army enlistment term to three years or “the duration of the war.” This effectively staved off the next manpower shortage until 1780.

Disputes over expiring enlistments had disastrous consequences. Alongside crippling logistical and supply deficiencies, enlistment contracts and soldiers’ pay were two most common causes for mutinies. At least fifteen major mutinies occurred during the war.[39]The largest occurred in the Pennsylvania Line on January 1, 1781, in Morristown, New Jersey. Two entire brigades, 1,500 rank and file soldiers, threatened to march on Congress in Philadelphia.

The soldiers complained their three-year enlistments were over, and they had not been paid for an entire year. Their commanding officer, Gen. Anthony Wayne, was not entirely surprised by the mutiny as he wrote months before it occurred: “Our soldiery are not devoid of reasoning faculties . . . Trifling as it is, they have not seen a paper dollar in the way of pay for near twelve months.”[40] The mutiny only ended when Joseph Reed, governor of Pennsylvania, personally negotiated the mutiny’s end by giving in to the soldiers’ demands. Over 1,300 soldiers were discharged from the army peaceably.[41]

The challenges in recruitment and reenlistment, as well as disputes of enlistment terms and ensuing mutinies, suggested that the primary motivation for enlisted soldiers in the Continental army may not have been purely patriotism, but that more tangible concerns motivated a diverse group of enlistees.

The Army’s Demography and Soldiers’ Motivations

After the initial patriotic fervor waned, recruitment efforts evolved by increasingly relying on coercion such as state drafts and pulling from society’s lower strata. The initial recruiting instructions from Horatio Gates “excluded all Negroes, vagabonds, British deserters, and immigrants.”[42] The exact opposite happened. To fill their quotas, recruiters could not be so discerning in their prospective enlistees. An estimated 90 percent of privates came from the poorest two thirds of the taxable population, especially from foreign immigrants. Irish immigrants accounted for as much as 25 percent of the total army, and as high as 45 percent of Pennsylvania’s recruits. German immigrants, including Hessian deserters from the British army, accounted for 12 percent of the Continentals. There was even a “German Battalion” from Pennsylvania.[43]

The Continental army also crossed racial barriers, becoming America’s first racially integrated army. Disregarding official instructions, some states recruited African Americans, both slave and free, to fill their quotas. Some slave-owners sent their slaves as substitutes for the state draft. By 1778, a special return from Adjutant General Alexander Scammel reported 586 African Americans out of a total of 14,509 men (4 percent). As many as 5,000 African Americans served in the Continental army throughout its existence.[44]

Beyond crossing boundaries on race, the army’s personnel also centered on youth. In one revealing letter, Washington complained: “I shall cut in it, when Inform you, that excepting about 400 recruits from the State of Massachusetts (a portion of which, I am told, are children hired at about 1500 dollars each for 9 months service).”[45] The official age range to enlist was sixteen to sixty, but many recruiters felt free to bend the rules.[46] Enlisted soldier Joseph Plumb Martin’s memoir confirmed this; he was only fifteen when he enlisted in 1776. Martin further recollected that peer pressure among youth was a significant factor. He recalled of his experience upon enlisting: “the old bantering began, come if you will enlist I will, says one,” as he recalled his own peers jostling his hand to sign the official papers. Martin later called enlisting his “heart’s desire,” expressing a youthful sense of grand adventure as part of his decision.[47]

Patriotic notions like freedom from Britain’s economic tyranny may not have been the prime motivation for many enlistees. More likely, they were motivated by steady pay, meals, clothing, and social advancement. Long term service to the army was an unyielding hardship. This made the matter of financial compensation all the more urgent.

Soldiers’ Pay

Hamstrung by a weak national authority, the Continental Congress and army were continuously unable to appropriately pay their soldiers during the war. Washington reflected on this issue: “In modern wars, the longest purse must chiefly determine the event—I fear that of the enemy will be found to be so.”[48] Pay never ceased to be an issue. The lack of pay compounded all other personnel challenges. It further hindered recruitment and reenlistment, and it added to the reasons for mutinies, desertion, and indiscipline. Had the army not successfully coped with this issue, the army could have very well dissolved before its opportunity to turn the tide of the war at Yorktown.

The army used a bureaucratic structure to pay its soldiers. Army paymasters took the total numbers from their units’ strength returns to request lump sums from Congress. Upon receipt, paymasters disbursed paper money to soldiers in their commander’s presence. Commanding officers verified and signed monthly payroll reports recording soldiers pay due, advances, and balances. Standard pay for a private soldier in the infantry was six and two-thirds dollars per month.[49]

Correspondence from army paymasters reveals a never-ending catch-up game. The total expenses for the army between January and May 1780 amounted to $1,690,000.[50] Paymaster James Pierce complained to the Board of Treasury in 1780, “I made a return for a million and a half dollars to pay the army for January and February, and have received only 500,000 dollars, being the whole that was in the treasury!”[51] Paymasters were forced to prioritize which units must be paid, and which could wait. For example, paymasters’ letters included lines such as: “I rather think they will not spare any money for your department at present, as there are other demands more pressing,” and “necessities of the two latter [departments] seem not to be very pressing.”[52]Even if they had the money on hand, it may not have done much good due to massive inflation.

As the war ground on, the already weak dollar became worthless. Congress introduced thirty-one million dollars into the American economy by the end of 1777.[53] Its value depreciated quickly. In 1780, one-hundred dollars was equivalent to the value of seventy-four cents in 1775.[54] Congress issued depreciation certificates as a reactionary measure to assure soldiers their pay would not be worthless. By 1781, the monetary system was in complete freefall, with Continental currency not even being accepted as legal tender.[55]

The financial system’s collapse severely impacted the war. Washington himself was content to serve without pay, but common soldiers were not so self-sacrificing. Speaking on the soldiers’ dependence on money, Washington wrote: “there is no Nation under the sun, (that I ever came across) pay greater adoration to money than they do.”[56] As seen in the Pennsylvania Line mutiny, it was not uncommon for soldiers to go long periods without receiving any pay at all. The situation was so bad that Alexander Hamilton believed restoring financial health was more important than winning battles; he wrote to Robert Morris: “Tis by introducing order into our finances—by restoring public credit—not by gaining battles, that we are finally to gain our object.”[57] Congress needed to take action to save the war effort.

Robert Morris, who became Congress’s superintendent of finance in 1780, played an invaluable role in addressing the pay issue. No single person had more impact on soldiers’ pay. He invested his own personal fortune and credit to pay the army on multiple occasions where he saved the army with immediate short-term financial fixes.

Morris’s actions were vital to the army’s success at Yorktown in 1781. Washington’s army, having linked up with French allies under General Rochambeau, marched over 450 miles south to seize the moment at Yorktown. Stopping in Philadelphia, Washington worried a lack of funds would prevent the army’s movement south and that unpaid soldiers may threaten mutiny. Washington implored Morris: “I must entreat you if possible to procure one month’s pay in specie . . . those troops have not been paid anything for a very long time past, and have upon several occasions shewn marks of great discontent . . . but I make no doubt that a douceur of a little hard money would put them in proper tempter.”[58] Scrambling to save the situation, Morris secured massive French loans at the last minute, allowing him to pay the army in valuable hard coin.[59] Additionally, Morris committed his personal fortune and created “Morris notes,” his own personal currency, to pay Philadelphian merchants and contractors to support the army’s logistical needs on the drive south.[60] Robert Morris’ decisive action in allaying the army’s financial straits in 1781 directly contributed to the victory at Yorktown.

Conclusion

Coping with the army’s personnel administration challenges was absolutely necessary to the revolution’s success. Many historians explain that Americans did not win, but rather they just “did not lose.”[61] By this, historians mean the Continental army by itself could never defeat the British. It was only French assistance that finally enabled the decisive blow at Yorktown. Comparatively, the British were never able to depart from their footholds in the coastal cities to eradicate the Continental army. In a sense, all the Continental army had to do was simply exist for the revolution to continue. Therefore, sustaining the army’s personnel was an imperative task. The army’s strength reporting, recruitment and retention, and financial payment were existential functions to prosecuting the revolution.

Describing a scenario in which Britain could win the war, Washington wrote: “Administration may perhaps wish to drive matters to this issue.”[62] The army successfully coped with major personnel challenges. They did so despite virtual financial disaster. Last-minute tactical maneuvers of paperwork prevented the army’s total collapse. Often overshadowed by more visceral military aspects, personnel administration had a crucial place in the Continental army, as it does in every military today. Army administrators, including Congress, commanders, staff officers, aides, paymasters, recruiters, and common soldiers alike, made victory possible. As these officers understood, the heart of any army, its most important resource, is its people.

[1]George Washington to Joseph Reed, January 14, 1776, William B. Reed, Reprint of the original letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, during the American Revolution. Referred to in the pamphlets of Lord Mahon and Mr. Sparks (Philadelphia: A. Hart, Late Carey and Hart, 1852), 44.

[2]Washington to Reed, January 4, 1776, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 36-37.

[3]Robert K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army (Center of Military History: United States Army, 1983), 55.

[4]Washington to Reed, January 14, 1776, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 43.

[5]Wright, The Continental Army, 24, 40.

[6]Washington to Reed, January 14, 1776, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 42.

[7]Washington to John Hancock, September 22, 1776, Lengel, ed. This Glorious Struggle: George Washington’s Revolutionary War Letters (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2007), 68.

[8]Washington to Lund Washington, December 10, 1776, ibid., 80.

[9]Washington to Hancock, December 20, 1776, ibid., 81.

[10]Robert Middlekauff, This Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 372.

[11]Wright, The Continental Army, 119.

[13]Humphrey Bland, A Treatise of Military Discipline(London: Daniel Midwinter, John and Paul Knapton, 1743) and William Young, Manoeuvres, or Practical Observations on the Art of War (London: J. Millan, 1770). Also see J. L. Bell, “Washington’s Five Books,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 18, 2013, allthingsliberty.com/2013/12/washingtons-five-books/.

[14]Washington to Reed, January 23, 1776, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 50.

[15]Ibid., 49. (for the five separate letters, see pages 12, 18-19, 28, 48, 54).

[16]Wright, The Continental Army, 26-27.

[17]Paul David Nelson, General Horatio Gates: A Biography (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1976), 43.

[18]Charles H. Lesser ed., The Sinews of Independence: Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1976), xiii.

[19]Wright, The Continental Army, 114, 145.

[20]Lesser, Sinews of Independence, ix.

[22]Washington, General Orders, January 8, 1776, John C. Fitzpatrick ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, U.S. Presidential Library, Vol 4, 223.

[23]Wright, The Continental Army, 40.

[24]Washington to Reed, December 15, 1775,Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 31.

[25]Lesser, Sinews of Independence, xxxi.

[26]PHILADELPHIA. IN CONGRESS, July 16, 1777, The Pennsylvania Gazette, July 23, 1777.

[27]Washington to Hancock, September 22, 1776, Lengel, This Glorious Struggle, 72.

[28]Charles Neimeyer, America Goes to War: A Social History of the Continental Army (New York and London: New York University Press, 1996), 136-138.

[29]PHILADELPHIA, April 20, 1777, The Pennsylvania Gazette, April 23, 1777.

[30]PHILADELPHIA IN CONGRESS, April 14, 1777, The Pennsylvania Gazette, April 23, 1777.

[31]Joseph Plumb Martin, A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier: Some of the Adventures, Dangers, and Sufferings of Joseph Plumb Martin (Signet Classics, 2010), 8.

[32]General Orders, Headquarters Morristown, February 6, 1777, PHILLADELPHIA, The Pennsylvania Gazette, February 19, 1777.

[34]Washington to Hancock, September 22, 1776, Lengel, This Glorious Struggle, 68-69.

[35]Washington to Reed, December 15, 1775,Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 29.

[36]Washington to Reed, August 22, 1779, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 127-128.

[38]Washington to Reed, August 22, 1779, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 127-128.

[39]Neimeyer, America Goes to War, 164.

[40]Anthony Wayne to Reed, December 16, 1780, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed. Vol II (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847), 316-317.

[41]Neimeyer, America Goes to War, 151.

[42]Quoted in Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 43.

[43]Neimeyer, America Goes to War, 19, 37-38, 50, 64.

[44]Noel B. Poirier, “A Legacy of Integration: The African American Citizen – Soldier and the Continental Army,” Army History no. 56 (Fall 2002): 16-25, 21, 24.

[45]Washington to Reed, July 29, 1779, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 122.

[46]John Ruddiman, Becoming Men of Some Consequence: Youth and Military Service in the Revolutionary War(Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2014), 7.

[48]Washington to Reed, May 28, 1780, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 139.

[49]Neimeyer, America Goes to War, 123.

[50]James Pierce to the Board of Treasury, Morristown, May 6, 1780. Saffell, W.T.R., G. Washington, C. Lee, N. Greene, and United States Continental Congress, Records of the Revolutionary War: Containing the Military and Financial Correspondence of Distinguished Officers; Names of the Officers and Privates of Regiments, Companies, and Corps, with the Dates of Their Commissions and Enlistments; General Orders of Washington, Lee, and Greene, at Germantown and Valley Forge; with a List of Distinguished Prisoners of War; the Time of Their Capture, Exchange, Etc. To Which Is Added the Half-Pay Acts of the Continental Congress; the Revolutionary Pension Laws; and a List of the Officers of the Continental Army Who Acquired the Right to Half-Pay, Commutation, and Lands (Pudney & Russell, 1858), 66.

[51]James Pierce to the Board of Treasury, April 10, 1780, Records of the Revolutionary War, 62.

[52]J. Burrall to Col Udney, and Thos. Reed, Records of the Revolutionary War, 53, 49.

[53]Wayne E. Carp, To Starve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture, 1775-1783(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 31.

[54]Clifford Rogers, Ty Seidule, and Samuel Watson eds., The West Point History of the American Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 186.

[55]Neimeyer, America Goes to War, 126.

[56]Washington to Reed, February 10, 1776, Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 61.

[57]Alexander Hamilton to Robert Morris, April 30, 1781, Founder’s Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-1167.

[58]George Washington to Robert Morris, August 27, 1981, Founder’s Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06802.

[59]Robert Morris to George Washington, September 6, 1781, Founder’s Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06906.

[60]Charles Rappleye, Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution(New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2010), 256-262.

[61]John Shy, A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 12.

[62]Washington to Reed, May 28, 1780,Letters from Washington to Joseph Reed, 140.

2 Comments

I’m sending this to every administrative person I know in the military today. Fantastic article.

Excellent article. I particularly found the section on Army Demographics interesting.

Just a note, Washington’s military family included twenty eight aides and four secretaries during the war as well as several unofficial aides. You are right, they were essential to any success the army had.

Thanks for a fine article.