Last spring, the Varnum Memorial Armory Museum in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, announced its discovery of a handwritten letter from a formerly enslaved man who had gained his freedom by enlisting in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment during the Revolutionary War. The letter, written in 1781, is one of only a few known existing letters sent by Black soldiers during the Revolutionary War, and it was from a soldier serving in Rhode Island’s famous “Black Regiment.”[1] This makes the find a remarkable one; indeed, it is a “national treasure” as the curator of the museum and discoverer of the letter, Patrick Donovan, states.[2] The contents of the letter are also noteworthy: the soldier made a shocking request of his former “master and mistress” who had once enslaved him.

The letter is from Thomas Nichols of Warwick, Rhode Island. It was sent to Benjamin and Phoebe Nichols of Warwick, who had once enslaved Thomas Nichols. According to Rhode Island’s 1774 census, Benjamin Nichols’ household contained two adult white men, two adult white women, three white children, two “Indians” (most likely servants of some kind since Rhode Island did not allow Native Americans to be enslaved), and one Black slave—Thomas Nichols.[3] A state military census for 1777 listed Benjamin and Thomas as able-bodied men between the ages of sixteen and sixty. In mid-1778, Thomas Nichols became free, escaping enslavement by enlisting in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Army.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment was re-established in February 1778 in order to entice enslaved men to join its ranks. The idea likely originated from white officers of the regiment, whose ranks had been decimated from difficult military campaigns around New York City and Philadelphia. The idea also had the implicit support of Gen. George Washington, who had forwarded the request to Rhode Island’s governor to re-establish the regiment with enslaved men.

On February 9, 1778, Rhode Island’s General Assembly enacted a law providing freedom to enslaved men who enlisted in the regiment. But there were a few important conditions. First, the enslaved man had to enlist for the duration of the war. Second, the enlistee’s former master or mistress was to be paid by the state an amount equal to the fair market value of the enslaved man, as determined by the state. In addition, under the statute’s structure, both the enslaved man and his owners had to agree to the enlistment.[4]

As it turned out, there were not enough enslaved young men in Rhode Island willing to enlist to fill a regiment. About ninety enslaved men did enlist, thus gaining their freedom. Free Black men, Narragansett Indians, and other men of color filled out the ranks of privates. The officers were all white men, including the regiment’s colonel, Christopher Greene of Warwick.

On May 10, 1778, Thomas Nichols enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island and was assigned to Capt. Thomas Cole’s company.[5] Nichols likely showed up at a muster organized by one of the regiment’s officers, with a drummer by his side to inspire the men with a drumbeat. Joining the regiment created a path to freedom, and so Nichols, along with other similarly minded enslaved men, voluntarily enlisted for the war’s duration. By virtue of joining the regiment, Nichols and the other enslaved men who had enlisted were now, according to the words of the statute, “immediately discharged from the service of his master or mistress” and “absolutely FREE.” In addition, they would now be fighting for the independence of the new United States. I discovered that probably more than a dozen of these formerly enslaved men had been born in Africa.[6] Now they would fight for the freedom of the country into which they had been forcibly carried.

On May 22, the State of Rhode Island issued a note in the amount of 120 pounds to Thomas’s former owner, Benjamin Nichols of Warwick. Thomas must have been healthy and strong, as 120 pounds was the maximum the state would pay owners of enslaved enlistees at the time.[7]

As with all the other enlistees, Nichols would have been inoculated against the smallpox at a safe house, probably in East Greenwich. Then military training with muskets and bayonets began in the town.[8] On May 31, 1778, Dr. Joshua Babcock, from Westerly, Rhode Island, wrote to his friend, Benjamin Franklin, then in France, “This sable battalion, well uniformed and well conducted, bid fair for service.”[9]

The new soldiers in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment had little time to train or gain experience in the field before facing a fierce baptism of battle. This was at the Battle of Rhode Island, on August 29, 1778. The American army, then in the northern part of Aquidneck Island and seeking to leave the island, had to fend off advances of British army troops. As I describe in my book, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment held a key redoubt on the west side of the norther part of Aquidneck Island at the most advanced—thus exposed—position of the American line. Three times experienced German troops, allies of the British, charged the redoubt and the American lines, and were repulsed by the 1st Rhode Island and other Continental regiments to their rear. One German officer stated, “we found obstinate resistance, and bodies of troops behind the work [the redoubt] at its sides, chiefly wild looking men in their shirtsleeves, and among them many negroes.”[10] Writing a few hours after the battle, the 1st Rhode Island’s field commander in the battle, Maj. Samuel Ward, wrote, “I believe a couple of the blacks were killed and four or five wounded, but none badly.”[11] It was an impressive performance by the regiment, especially considering how inexperienced in combat the men were and that as enslaved men they had never been allowed to use guns or participate in militia exercises.

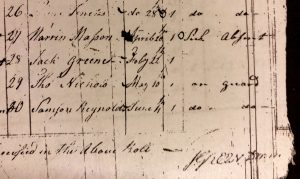

Thomas Nichols very likely fought at the Battle of Rhode Island. In a muster roll taken in late August 1778, Nichols is reported as with the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. In a muster roll dated August 23, 1778, when the First Rhode Island Regiment was stationed on Aquidneck Island and just six days before the battle, Nichols is reported as “on guard”with the First Rhode Island Regiment. However, in the next month’s muster roll, he is reported as “Sick in hospital.”[12] It is not clear if Nichols had been wounded during the battle or suffered from an illness. Shortly before the battle, the regiment had suffered from an outbreak of disease, and Nichols may have become a victim of the outbreak after the battle.[13] During the war, on both sides, more soldiers died of disease than from bullets and cannon fire. Based on other descriptions in regimental muster rolls of Nichols being “sick,” and that in his January 1781 letter Nichols states that he was suffering from illness and not from wounds, it appears more likely he became ill after the battle and was not wounded. Curator Patrick Donovan appropriately wonders if Nichols suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.[14]

Nichols was still reported as “sick” in a muster roll return submitted in May 1779 in Rhode Island. But he had apparently sufficiently recovered after that time to be listed in subsequent rolls as “on command” or “on guard”—that is, he was acting in a normal capacity.[15] Nichols was with his regiment when the British evacuated Newport and American regiments re-entered it in late October 1779. The muster roll for his company on January 7, 1780, from Newport, indicated Nichols was “on command.”[16] But a year later, by January 18, 1781, the date of the recently-discovered letter, he had either suffered a relapse of his former illness or he had acquired a new debilitating disease.

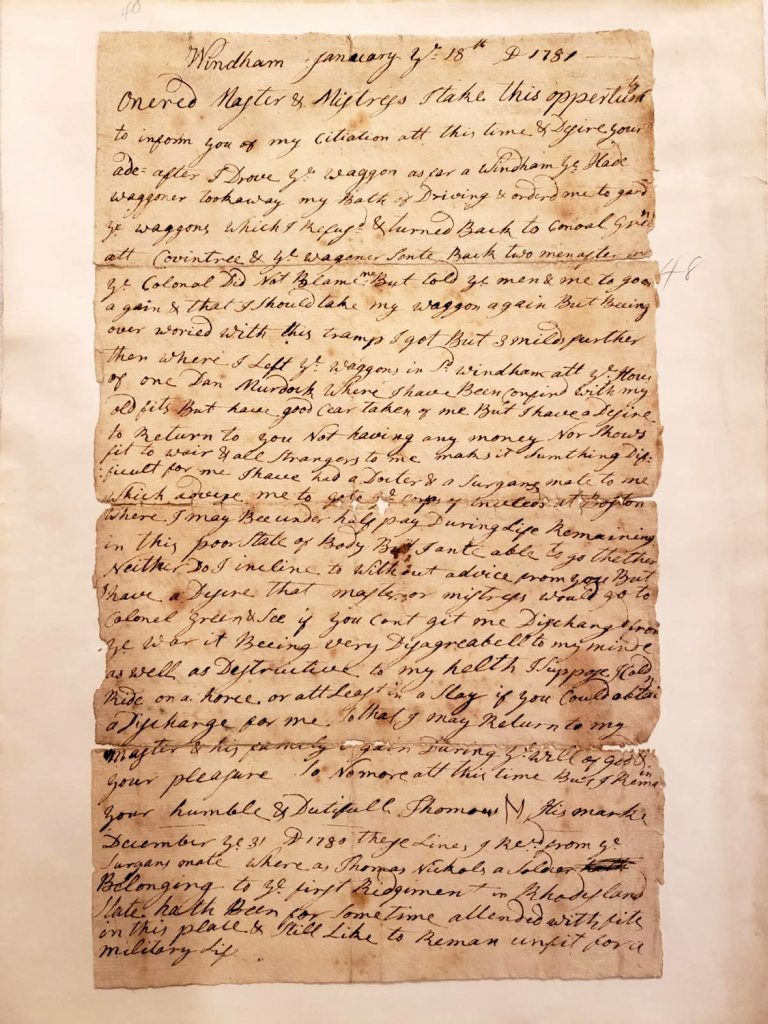

Now let’s turn to Thomas Nichols’ letter. The transcription below has corrections to misspellings and punctuation, and a few words revised to reflect the intended meaning; the original text of the letter appears at the end of this article. After the letter, I will address its substance.

Windham [, Connecticut,] January 18th, 1781

Honored Master & Mistress:

I take this opportunity to inform you of my situation at this time and desire your aide. After I drove 3 wagons as far as Windham, a wagoner took away my badge of driving and ordered me to guard the wagons, which I refused. I turned back to Colonel Christopher Greene at Coventry and the wagoner sent back two men after me. The Colonel did not blame me but told the men and me to go on again and that I should take my wagon again. But being over worried with this tramp I got but 3 miles further than where I left the wagons in South Windham at the house of one Dan Murdock where I have been confined with my old fits. But good care is taken of me. But I have a desire to return to you. Not having any money, nor clothes fit to wear and all strangers to me makes it something difficult for me. I have had a Doctor and a Surgeon’s Mate [examine] me who advise me to go to the Corps of Invalids at Boston, where I may be under half pay during the life remaining in this poor state of body. But I am not able to go there. Neither do I incline to do so without advice from you. But I have a desire that Master or Mistress would go to Colonel Greene and see if you can’t get me discharged from the war, it being very disagreeable to my mind as well as destructive to my health. I suppose I could ride on a horse or at least in a slay if you could obtain a discharge for me so that I may return to my master and his family again, bearing the will of God and your pleasure. So no more at this time. But I Remain your humble and dutiful Thomas.

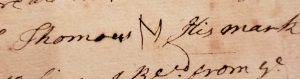

“N” His mark

December 31, 1780. These lines I received from the Surgeon’s Mate: Whereas Thomas Nichols a soldier belonging to the First Regiment in Rhode Island State has been for some time attended with fits in this place and still likely to remain unfit for military life.

In the letter, Nichols initially explained the incident that inspired him to write. The 1st Rhode Island Regiment was at the time stationed at Coventry, Rhode Island, and Nichols had been ordered to drive a wagon from there into Connecticut, probably to pick up grain or other foodstuffs and return it to Coventry for the troops. But during the trip, near Windham, Connecticut, Nichols must have become so incapacitated from the onset of illness that he was unable to perform his assigned duty. A wagoner supervising him removed his badge that entitled him to drive a wagon for the Continental Army and ordered him to serve just as a mere guard for the wagons. Nichols refused the demotion and instead drove his wagon back to Coventry to meet with the commander of his regiment, Colonel Greene. Fortunately for Nichols, Greene did not punish him for disobeying orders. Rather, Greene ordered Nichols to drive his wagon back to Connecticut and try to complete the task assigned to him. Nichols made the attempt, but he got no farther than three miles from South Windham when illness again overwhelmed him. Luckily for him a local man, Dan Murdock, invited him to stay at his house and took “good care” of him. At the time he wrote the letter, January 18, 1781, Nichols still suffered from his “old fits” and was not well enough to leave Murdock’s house.

Thomas desperately wanted to be discharged from military service. His reasons were that the war was “very disagreeable to my mind” as well as “destructive to my health.” Thomas no longer relished being a soldier and it had ruined his health.

After providing Benjamin and Phoebe Nichols with this background, Thomas Nichols made the following startling request: “I have a desire to return to you.” Later he stated (in the third person) that, for reasons of his poor health, “I have a desire that Master or Mistress would go to Colonel Greene and see if you can’t get me discharged from the war.” He again reiterated his desire for his former owners to “obtain a discharge for me so that I may return to my master and family again.”

Did Thomas Nichols want to be re-enslaved? The use of the terms “master” and “mistress” evoke the master-slave relationship and he expressed a desire to “return to my master and family again” (emphasis added). But Thomas did not use any other language indicating that he wanted to return to the legal status of enslavement. Perhaps he was deliberately ambiguous. He may have wanted his former owners in the short term to take him back in and care for him, and at the same time defer until later negotiations with them over his free or unfree labor status.

Thomas Nichols must have been in a severe psychological state to have even intimated that he desired to return to a possible state of enslavement. But poor health, the pressures of war, and the uncertainty of his economic future due to his disability could explain a temporarily disturbed state of mind. He apparently felt at the time that spending the rest of his days with his former master and mistress provided him with more security than struggling to live on his own in his unhealthy condition. It is also an indication that the white Nichols family may not have been cruel masters.

Benjamin and Phoebe Nichols might not have been able to re-enslave Thomas even if they had tried. There was no provision for it in the General Assembly’s legislation authorizing the re-establishment of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. For Thomas to have obtained his freedom by enlisting, he had to enlist for the duration of the war. That condition implied that if a soldier deserted the regiment, he could be returned to slavery. But if the soldier was discharged for bad health that he acquired while on duty in his regiment or for battle wounds, the Rhode Island statute provided that such soldiers were not to be returned to slavery, but instead would be supported by the state.

In addition, Benjamin and Phoebe Nichols may not have wanted to re-enslave Thomas Nichols. At the time, Rhode Island’s economy was in a shambles, and the white Nichols family may not have wanted another mouth to feed. In addition, they had allowed Thomas to enlist, a condition to receiving compensation from the State of Rhode Island for losing him. They may have been concerned that the State of Rhode Island would demand repayment of a portion of the compensation paid to the Nichols family for Thomas’s enlistment.

The situation is reminiscent of the implied moral obligation of enslavers to care for their elderly enslaved persons. In colonial times, it was considered cruel by enslavers to free an enslaved man or woman after a lifetime of unpaid service and at a time when he or she was too old or infirm to perform further useful work to support himself or herself. Thomas Nichols was in effect asking his former white owners to care for him at a time when he was unable to perform exacting manual labor. But as Benjamin and Phoebe may have viewed it, Thomas had not become incapacitated in their service; rather it was from his service in the Continental Army. At the time, the fledgling United States did not care for its wounded or ill veterans, and Rhode Island had not begun to fulfill this obligation either.

One reason Thomas Nichols found himself in this situation was because he had been enslaved. A typical white soldier had parents working on a family farm who made a decent living and could have taken their sick son in, cared for him, and nursed him back to health. Or other relatives could have done so. But Thomas Nichols’ parents—if the were alive—likely continued to be enslaved persons and thus were not able to perform this crucial task that families sometimes were forced to undertake to assist their children. This was yet another penalty the slave system imposed on its victims.

In his letter, Thomas Nichols described the “poor state” of his health and dire financial situation. He did not have “any money, nor clothes fit to wear.” This was the fault, of course, of Congress and Rhode Island in failing to provide properly for their soldiers. Both white and Black soldiers suffered from such lack of support, especially beginning in the winter of 1778-1779 and for the remainder of the war. This sad state of affairs led to some mutinies among white soldiers, including in Rhode Island.[17]

Nichols also explained that he had been examined by his regiment’s doctor and a surgeon’s mate, both of whom agreed that Nichols was not fit to perform further military service. The postscript to the letter appears to be a paraphrasing of the conclusions of the surgeon’s mate. He concluded that Nichols “has been for some time attended with fits” and was “likely to remain unfit for military life.” The regimental surgeon and surgeon’s mate, however, rather than agreeing that Nichols should be discharged from military service, advised Nichols that he should be transferred to the “Corps of Invalids at Boston” where he could earn “half pay.” The Corps of Invalids was filled with Continental Army soldiers from various regiments who had suffered debilitating wounds or illness, making them unable to endure the rigors of a campaign, but leaving them healthy enough to perform less demanding tasks such as guarding forts, prisons and hospitals.

It is not known if either Benjamin or Phoebe Nichols approached Colonel Greene about obtaining a discharge for Thomas Nichols. (It is noteworthy that Thomas was willing for Phoebe to make the request on her own, an indication of his confidence in her abilities.) They had little time to act. The muster rolls for the 1st Rhode Island Regiment indicate that Thomas Nichols was transferred to the Corps of Invalids on February 1, 1781.[18]

Thomas Nichols wrote his mark on the letter with an “N.” Who penned the letter from his dictation is unknown. It was probably Dan Murdoch or someone who lived in his house or nearby. Common soldiers not infrequently were illiterate and had other soldiers, often corporals or sergeants, write their letters for them. But at the time of this letter, Thomas Nichols was in the house of a civilian and not at a regimental camp.

What became of Thomas Nichols after war’s end is not known. The 1790 federal census of heads of households contains an intriguing clue. It does not mention a Black man named Thomas Nichols as heading a household in Rhode Island, but it does contain an entry for Benjamin Nichols heading a household of ten persons. In the Rhode Island 1774 census, as mentioned above, in addition to the seven white family members in Benjamin’s household, there were also two Indians and one Black person, who must have been the enslaved Thomas Nichols. In the 1790 federal census, Indians and Blacks were not categories. Instead, persons of color were covered by the two categories “All other free persons” and “Slaves.” The entry for Benjamin Nichols in the 1790 census includes three white adult males, four white females, three free persons of color, and no slaves.[19] Accordingly, the size and makeup of the household was the same in 1790 as it was in 1774—seven whites and three persons of color. Perhaps the persons of color in the household in 1790 were the same two Indians who were in the Nichols household in 1774—and Thomas Nichols, but as a free man. If so, Thomas Nichols was granted his wish to return to the Nichols family, but he was able to negotiate his status to remain a free man.

The 1790 census for Stratford, Connecticut, located in Fairfield County, contains the following item: “Thomas (Neg.) Nichols” using an abbreviation for the word Negro. This could be a reference to Thomas Nichols, the letter writer. The entry indicates that four other nonwhite persons resided in this household, perhaps the man’s wife and three children.[20] This record might tie into the fact that Thomas Nichols does not appear on a list of invalid soldiers residing in Rhode Island in 1785—he may have moved to Stratford.[21]

After this mention, the documentary record for Thomas Nichols is missing. This is not uncommon after a certain point in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, either for a white or a Black person, but it is more common for Black persons. Thomas Nichols apparently did not live long enough to apply for a veteran’s pension in either 1818 or 1832. Perhaps his bad health arising from his military service finally caused his early death sometime after 1790. More research is needed to find out the rest of Thomas Nichols’s story after his transfer to the Corps of Invalids in February 1781.

The Thomas Nichols Letter has been professionally conserved by the Varnum Armory Memorial Museum, thanks to a grant from the Rhode Island Sons of the American Revolution. The letter is now on display in a frame in the museum’s Eighteenth Century Room. Patrick Donovan and the Varnum Armory Memorial Museum are to be congratulated on their spectacular discovery.

Transcription of the Thomas Nichols Letter, Uncorrected

Windham January 18th, 1781

Onered Master & Mistress I take this opportunity to inform you of my citiation att this time & desire your ade = after I drove 3 waggons as far as Windham I hade waggoner tookaway my badge of driving & ordered me to gard ye waggons which I refused & turned back to colonel green att Covintree & ye wagoner sent back two men after me Ye Colonal did not blame me but told ye men and me to go on again & that I should take my waggon again but being over worried with this tramp I got but 3 miles further than where I left ye waggons in So. Windham att ye house of one Dan Murdock where I have been confined with my old fits But have good care taken of me But I have a desire to Return to you Not having any money Nor Clows fit to wair & all strangers to me makes it something difficult for me I have had a Doctor and a Surgans mate to me which advize me to go to xxx corps of invalids at Boston where I may be under half pay During Life Remaining in this poor State of Body But I ante able to go thether Neither do I incline to with out advice from you But I have a desire that Master or Mistress would go to Colonel Green & see if you cant git me Discharged from ye War it being very Disagreabell to my mind as well as Destructive to my helth I suppose I could ride on a horse or att least in a Slay if you could obtain a Discharge for me So that I may Return to my Master and his family again baring[?] the will of god & your pleasure So No more att this time But I Remain your humble & dutiful Thomas “N” His mark

December 31 1780 These lines I recv’d from ye Surgeon’s mate where as Thomas Nickols a soldier belonging to ye first Regiment in Rhode Island State hath been for some time attended with fits in this place & still likely to Remain unfit for military life.

[1]At this writing, three letters by Black soldiers of the Revolutionary War are known to survive: the letter by Thomas Nichols described in this article; a letter by John Lines to his wife Judith, featured in another Journal of the American Revolution article; and a letter by Caesar Phelps to his master, Charles Phelps, www.pphmuseum.org/slavery-and-servitude-at-forty-acres-blog/2018/6/27/caesar-phelps.

[2]Patrick Donovan, “Thomas Nichols Letter at the Varnum Armory . . . a Stunning 18th-Century African American Artifact,” varnumcontinentals.org/2021/02/feature-article-thomas-nichols-letter-at-the-varnum-armory-a-stunning-18th-century-african-american-artifact/. Donovan’s discovery was highlighted in a front page article, Paul Edward Parker, “Echoes of the Past,” Providence Journal, February 15, 2021, p. 1.

[3]John R. Bartlett, ed., Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations 1774 (Providence, RI: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 64; Mildred M. Chamberlain, ed., The Rhode Island 1777 Military Census (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1985), p. 119. The original source for Benjamin being the owner of Thomas is the General Treasurer’s Accounts cited in note 7 below. The name of Benjamin’s wife is dervied from Patrick Donovan’s article cited in the first note above.

[4]General Assembly Resolution, February 9, 1778, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 8 (Providence, RI: A. C. Greene & Bros., 1863), 358-60. For more on the First Rhode Island Regiment, see Robert Geake and Lorén Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2016); Daniel M. Popek, They “. . . fought bravely, but were unfortunate:” The True Story of Rhode Island’s “Black Regiment” and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island’s Continental Line, 1777-1783 (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2016).

[5]Thomas Nichols Service Records, Derived from Company Muster Rolls July 6, 1778-May 4, 1781, in Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army during the Revolutionary War, M881, Washington, DC: National Archives, Washington, D.C. (hereafter “Thomas Nichols Service Records”).

[6]An incomplete muster roll lists thirty-three former enslaved soldiers from the First Rhode Island Regiment and describes eight of them has being born in Africa and one as being born in Jamaica. List of Soldiers, 1781, Regimental Book, Rhode Island Regiment, 1781-83, microfilm, R.I. State Archives. While this regimental list was compiled in 1781, it contains information relating to privates who had enlisted in the First Rhode Island in 1778.

[7]An Account of the Negro Slaves Enlisted into the Continental Battalions, to whom they belong, with the valuation of such Slave, and Notes Given, General Treasurer’s Accounts, 1761-1781, Alphabetical Book, No. 6, R.I. State Archives. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of R.I., 8: 360.

[8]Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014), 48.

[12]Thomas Nichols Service Records, September 1778 (“Sick in hospital”); December 1778 (“Sick Absent”); January 1779 (“On duty”); February 1779 (“Under guard”); April 1779 (“On guard”); May 1779 (“Sick” at Quidnessett); July 1779 (“On Guard”); August 1779 (“On Guard”).

[13]McBurney, Rhode Island Campaign, 199.

[14]Donovan, “Thomas Nichols Letter at the Varnum Armory.” Daniel M. Popek, in his exhaustively researched work on the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, after studying the evidence he uncovered about the battle, leaned towards Thomas Nichols being among the regiment’s men wounded in the battle. Popek, The True Story of the “Black Regiment, 233-34.

[15]Thomas Nichols Service Records, August 1778 to December 1779.

[16]Ibid., November-Dececmber 1779.

[17]See Christian McBurney, “Mutiny! American Mutinies in the Rhode Island Theater of War, September 1778-July 1779,” Rhode Island History, vol. 69, No. 2 (Summer/Fall 2011), 47-72.

[18]See Thomas Nichols Service Records, February 1780 to May 1781. Another source indicates that the transfer occurred on March 1, 1781. See Bruce C. MacGunnigle, Regimental Book: Rhode Island Regiment for 1781 &c.(East Greenwich, RI: Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 2011), 71.

[19]Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, Rhode Island (Bureau of Census, ed.) (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 14 (under Warwick). Curiously, there is no mention of Benjamin Nichols’s household in a Rhode Island 1782 census. See Jay Mack Holbrook, Rhode Island 1782 Census (Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979).

[20]Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, Connecticut, 31. This reference was mentioned in Eric G. Grundset, ed., Forgotten Patriots, African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008), 223. No Black man named Thomas Nichols hailing from Connecticut was reported as a soldier in the Revolutionary War. See ibid., 270-295.

[21]List of Invalids, June 7, 1785, in Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of R.I., 10: 162-67. The list includes several Black soldiers of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment.

8 Comments

Great article as always Christian.

Excellent article!

In my research on soldiers from the southern states I believe there were (comparatively) many more enslaved soldiers than have been documented. Clearly more research is needed on this topic but the dearth of primary sources is a challenge.

Interesting article. But when you say Nichols was in “a temporarily disturbed state of mind” and a “severe psychological state to have even intimated that he desired to return to a possible state of enslavement,” you are reading modern opinions into the text. While you could be right, I think he could very well have been asking because of considered and well reasoned desires.

I agree. And Thomas’ careful consideration may likely have been at that time surviving on your own especially maybe with a pervasive seizure condition could very well be a quick trip into subsistance if not outright starvation.

Thanks Matt, Douglas and Joshua! Joshua, you make a fair point, but if I went there, it would have required a lot of explanation, which I did not have space to do. It makes for an interesting topic, but is so counter-intuitive, that it requires much explanation. I did describe some of his possible motivations too. In addition, the other paragraph suggests that he may have really wanted to negotiate his status. Thanks, Christian

Understood, thanks for the reply.

It may not be the same Thomas Nichols, but the Valley Forge Muster Roll has a listing for a Private Thomas Nichols of the 1st RI. This listing doesn’t necessarily mean he was at Valley Forge, since the rolls for the 1st RI on that site seem to be a bit muddied due to its odd circumstances at the time. It lists his birth year as 1723, making him around 54 years old at the time of his enlistment in 1777. It also lists a year of death of 1784. That would explain why he never claimed a pension in 1818 or 1832, but would confuse the research regarding the 1790 census.

While searching for ancestors who served in the Revolutionary war I happened upon Thomas. Though I’m dismayed at the thought of Benjamin and Phoebe owning slaves. I really hope it is true that they had heart to take Thomas in in his time of need. Benjamin’s is 8 generations direct line to my father.

Thanks for the article. Joan Nichols Foren