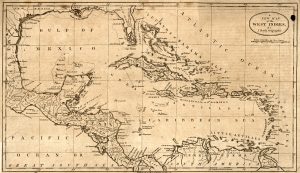

The two forces of paternalism and slavery shaped the lives of Loyalist slaveowners in the postwar British Empire. Historians rarely connect these forces in attempts to understand the relationship between refugees, colonial hosts, and British officials. In the postwar era, British officials treated Loyalists as an itinerant population to resettle to aid imperial expansion. In Canada, Loyalist refugees received lands on the northern frontier. The towns and trade networks established by Loyalists served as inroads for further settlement. To this day, British Canadians regard Loyalists (and free and enslaved African Americans) as the founders of the colony. Across the ocean, the British founded Sierra Leone as a colony for free Black Loyalists. The overarching mission of the colony was to serve as an entrepôt for the colonization and Christian conversion of western Africa. Jamaica presents a different case. Far from a frontier outpost, the island was the most profitable colony in the realm. The creole population had already settled most of the arable land. British authorities shipped in eight-thousand Loyalists (who brought with them two-thousand enslaved Blacks) to bolster the creole population, which was outnumbered ten-to-one by enslaved people. Thus, Loyalists across the Atlantic world benefitted from both the paternalism and the commitments to slavery in the British Empire.

Revolutionary America

In 1785, in his Historical view of the Commission for enquiring into the losses, services, and claims of the American Loyalists, John Eardley-Wilmot remarked with remarkable clarity at the unrest in the former Thirteen Colonies:

Civil Wars are always the most difficult to describe . . . particularly because their first causes and origin are soon lost sight of among progressive and increasing animosities; these alternatively giving place to a complication of mutual reproaches and injuries, and last ending in actual hostility and open war.[1]

Both rebels and Loyalists engaged in a brutal partisan war that played out on the local level. In most communities, vigilante gangs engaged each another in the absence of uniformed troops. The impacts of this dirty war fell especially heavily on women and children. It was common for women to manage the family farm, plantation, or business after their men departed for war. Moreover, the responsibilities of estate management were often thrust upon them when their men were arrested, evicted, or killed. The expectations for women’s wartime roles exposed women to partisan raids and the accompanying rape, arson, and theft. Thus, the decision for Loyalist women to abandon their property and flee to British-held cities had practical value.

In northern colonies, the city of New York was the favorite destination for Loyalist refugees. Southern Loyalists moved primarily to Savannah or Charles Town (renamed “Charleston” in 1783 to loosen ties with the city’s colonial past). Unable to return “home” after the war, Loyalist refugees departed the former colonies with hopes of rebuilding their lives elsewhere in the empire. Jamaica was by far the favorite destination for Loyalist slave-owning refugees. Southern planters and farmers aspired to the mythical wealth and status of the Caribbean sugar planters. Jamaica was the wealthiest and most developed island in the Caribbean, with an enslaved labor force that comprised ninety percent of the population. The entrenched planter class, however, resisted the immigration of Loyalists and their enslaved property. Most refugees arrived landless, penniless, and sick.[2] Jamaican slaveowners connoted freedom (and free people) with individual agency and control over one’s movement. The hazy, semi-free status of refugees led planters to question the social standing of Loyalist refugees.

Both “refugees” and “migrants” comprised the Loyalist exile to Jamaica. Whether one was a refugee or migrant was determined by their social and economic status during the war. Those with substantial means and connections could afford to emigrate from the colonies to avoid substantial losses. Those with less means remained in British-occupied cities until the war ended in 1783, then relied on paternalistic officials to cover their evacuation. The former were largely slaveowners who chose to migrate to Jamaica, where they could rebuild their lives using enslaved labor. The Jamaican Assembly later contested the aid claims of these “free migrants,” citing their lack of legitimate need for protection. The Assembly treated poor Loyalists as deserving of alms since their emigration from the American colonies was involuntary. Most poor refugees, if given a choice, would have chosen almost anywhere other than Jamaica. The island’s reputation as a black hole of disease and slave rebellion was legendary. Further, the poor did not possess the capital, knowledge, or resources to become planters. They were contented with keeping their family and limbs intact through their ordeal. Thus, the paradox of choice and deservingness shaped the postwar experiences of Loyalists.

Yet Loyalist slaveowners insisted that their identity as British subjects and as slaveowners set them squarely in the planter class. The entrenched planters resisted the incursion into their world. By the 1780s, a rigid class system had divided creole society into planters, professionals, artisans, and poor laborers descended from indentured servants. Loyalists did not fit neatly into this hierarchy. Like most refugees, Loyalists existed in a state of past and present that prevented them from integrating into their host society. The tensions among refugees and host subjects in the British Atlantic affords valuable insight into the ways that subjects identified themselves and located their position within the imperial framework.

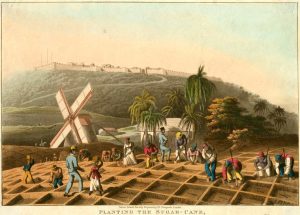

In Jamaica, white Loyalist slaveowners provide a valuable perspective on the enslaved labor regime. The labor scheme depended on imperial aid in the form of two army regiments and a naval command stationed in Kingston. The army served the dual role of imperial vanguard and slave police. The navy ensured that inbound shipments of African captives reached the port and protected the outbound merchant vessels carrying sugar, rum, and molasses. In short, the King’s forces ensured that sugar production was handled with order and security. During the Revolutionary War, Jamaican settlers remained loyal to Britain out of military and economic necessity. The eighteenth-century Caribbean was a hotbed of imperial warfare. Jamaica was under constant threat from foreign navies, slave revolts, and disease. Like Barbados and Trinidad, Jamaica only existed because of constant imperial surveillance and intervention. The enslaved population would quickly turn on the creole minority if not for the protection of the metropole.

This protection came at a steep cost in the 1770s and 1780s. The island endured a prolonged food shortage due to an imperial mandate that Jamaica not trade with rebelling colonies on the mainland. The sugar island relied on imported grains, beef, salted fish, and cheese as well as lumber and textiles from the mainland. The shortage fell especially hard on the enslaved, who experienced the blight as an all-out famine. A dozen hurricanes and two earthquakes also struck the island in this period. Needless to say, Jamaicans resented the presence of refugees who received stipends and tax breaks well into the 1780s. That London elevated the priorities of Loyalists over their own was a major source of tension between creoles, Loyalists, and British officials. This tension prompted Jamaicans to question their place in the rapidly shifting postwar empire. A barrage of hurricanes, slave revolts, imperial wars, and disease including the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic pulled the slave society to its knees. Loyalists observed the society buckle as the contradictions of paternalism and slavery became unmanageable.

Colonial Identity

The Revolutionary War exaggerated the crisis of identity in the British Empire. After a series of costly imperial wars in the mid-eighteenth century, London imposed greater metropolitan control over the colonies through taxation and oversight. American colonists reacted to growing parliamentary high-handedness with profound mistrust. Since the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Britons and their colonial descendants insisted that they possessed the same legal rights as subjects in the metropole. Colonists imagined themselves under a seamless legal and institutional tapestry that evenly covered every subject in the realm, regardless of their geographic or social position.[3] Events in the decades after the Seven Years’ War challenged this vision of universal legal rights.

In the colonial mind, the right to liberty was synonymous with property ownership. A challenge to liberty equated to a threat to one’s estate and everything they owned. Colonists across the ideological spectrum disagreed with the Parliamentary intrusions on colonial liberty. In the 1760s and early 1770s, the commitments of colonists to remain in the empire were voiced in the petitions of colonial officials to the House of Commons, but a series of military and political skirmishes led by radical secessionists forced the colonists past the point of negotiation. Still, London attempted to diplomatically resolve the conflict on several occasions, notably the Carlisle Peace Commission in 1778, which offered the American colonies Parliamentary representation in the empire. Loyalists approved of this peaceful resolution that allowed colonists to retain their rights to property and freedom within the empire, but rebels rejected the offer in favor of a republican government in which the right to private ownership would be foundational. The motivations of colonists on both sides of the spectrum are clarified by recognizing the centrality of property and slavery (a distinction slaveowners did not recognize) to the conflict.

The civil war cannot be neatly distilled into an “us” versus “them” dichotomy. Most colonists held similar interests in the conflict. Loyalist slaveowners shared the same interest in preserving rights to property—upon which the institution of slavery stood—as rebellious slaveowners. The difference was the side that individuals, not groups, thought would best uphold slavery during and after the war. The centrality of slavery to the decision-making of slaveowners shaped British strategy in the South. For reasons already discussed, the British supported the institution to prevent further rebellion and maintain the loyalty of the slave-owning class.

Scholars of the Revolutionary era frequently capitalize the term “Loyalist.” This construct leads to the false assumption that Loyalists comprised a monolithic and united political class. This united vision was constructed by contemporary British officials who, amid civil war, treated non-rebels as a hegemonic group with shared affection for the empire. Robert Zetter’s seminal examination on the functions of “labeling” highlights that London officials’ treatment of Loyalists reflected not wartime reality but policy intentions. He writes, “Labels do not exist in a vacuum. They are the tangible representations of policies and programmes.” The labeling of displaced colonists as “Loyalists” was “a convenient and accepted shorthand” in official narratives seeking to understand the conflict.[4] An examination into the priorities of Loyalists shows that most subjects cared more about their family and property than about the sovereign father, King George III. Furthermore, colonists often switched sides based on local circumstances. The sight of an inbound army or rumor of a slave revolt was enough to convince most colonists to turn their coat. The motivation to switch sides was even greater when faced with local threats to one’s family, estate, and enslaved property.[5] Recognizing the nuances among Loyalists complicates our understanding of the mentalities of Loyalists.

The term “Black Loyalist” is especially problematic. Most free Blacks held no loyalty to the King-in-Parliament, they simply desired to maintain their status as free people. Not surprisingly, African Americans reserved suspicion for British authorities that simultaneously upheld the freedom of free Blacks while supporting the institution that held others in lifetime bondage.[6] More than anyone, free Blacks understood that the empire’s commitment to the institution of slavery trumped any individual assertions of freedom. The 1775 proclamation of Lord Dunmore, the last royal governor of Virginia, provided the opportunity for manumission for rebel-owned Blacks but not for enslaved peoples owned by Loyalists.[7] British troops actively returned escaped Loyalist-owned Blacks to their owners. Thus, the Union Jack represented continued enslavement for African Americans owned by those loyal to the empire. This paradox was the cornerstone of the British southern strategy to maintain the loyalty of slaveowners and prevent the outbreak of race war.

The free and formerly enslaved African Americans who joined the Loyalist exodus held a rare status in the British Atlantic. The exact number of free Blacks who emigrated to Jamaica remains unclear. Most Blacks aboard the British transports from Charles Town and Savannah remained in bondage to Loyalists. The three-thousand Loyalists managed to take with them eight-thousand enslaved Blacks. The majority of the immigrants to Jamaica were enslaved, and the British navy paid for their transport. The free Blacks joined a free mixed-race population of ten-thousand, the largest ethnic group in Kingston.[8] The most notable among them was George Liele, the formerly enslaved Baptist minister who founded the first Baptist church on the island. The planter class reacted harshly to Liele’s liberatory message, which rang more like a call for insurrection than for spiritual enlightenment. As revolutionary upheaval continued to wash over the Caribbean in the 1780s and 1790s, the Jamaican Assembly passed sedition laws intended to quash Black evangelicals and prevent the conversion of the enslaved underclass. In 1794, in the heat of the Haitian Revolution, Liele was briefly imprisoned for sedition charges and his ministry faced sustained persecution.[9] He soon witnessed the authoritarian face of the empire that strived above all else to uphold order amid mass enslavement. His ordeal revealed the paradox of order and morality that defined the post-revolutionary British Empire.

Loyalist Aid Claims

In September 1783, Parliament enacted the Loyalist Claims Commission in response to the concerted lobbying of Loyalist officials, including Joseph Galloway, William Franklin, and former Georgia Governor William Wright. The Loyalist lobby argued in an anonymous pamphlet (probably penned by Galloway) that it was “their Right to receive compensation from this Government.”[10] It was their view that the Treasury was accountable for losses incurred by loyal subjects in the civil war. London officials took the position that Loyalist refugees had no right to aid, but that the “honor of the nation” and the paternalism of the king required it. The Commission was unprecedented in the scale and manner of its provisions—providing stipends, free passage, and land grants to dispossessed Loyalists. The Commission was the first of its kind in the early modern world. At a time when virtually all welfare came from private donations, the idea that the government would provide for the financial restitution of its subjects was revolutionary.[11]

Kristin Yarris and Heide Castaneda explain that refugees are a political class made vulnerable through war, violence, or natural or manmade disasters. Because they are involuntarily displaced, refugees are framed by the international community as in need of both physical protection and economic security because they were forced into displacement.[12] According to this definition, all dispossessed Loyalists met the twentieth-century definition of “refugees.” To this definition, the Commission added requirements of personal sacrifice and loyalty to the Crown. Claims that did not meet the standard of sacrifice—an arbitrary and subjective metric—were denied, or allotted lesser amounts of aid.

The high-handedness of London officials led Loyalists to exaggerate their sacrifices to the empire, weaving heart-wrenching narratives of poverty, despair, and loss. Below the surface, these performances reveal a trove of information on the families, estates, mentalities, and movements of the dispossessed. Women comprised the majority of claimants. Men often had their womenfolk submit petitions for the family, believing that paternalistic officials would reward women refugees with more generous allotments.[13] The gendered aspect of claims also spoke to women’s commitments to slavery. Historians often frame women slaveowners as passive and reluctant participants in the institution. The claims submitted by women slaveowners showed that women upheld the institution for its benefits of social and financial security.[14] The claims also disclose a fragmentary record of Loyalist-owned Blacks, often noting bondmen by name and occupation. Any honest reporting of the enslaved was rare. Slaveowners often lied about the quantity and makeup of their enslaved property to avoid taxes.[15] The kernels of truth in the Commission allow us to piece together the underexplored lives of enslaved Blacks and their Loyalist owners.

The contention over rights and privileges that ignited the Revolution also fueled tensions between Loyalists and London. The Commission did not judge claims on level ground, instead, basing the value of claims on the perceived loyalty of claimants.[16] The arrival of some ten-thousand displaced colonists and enslaved Blacks threatened to overturn the fragile social order on the island. The Assembly allocated funds for almshouses already serving the underclass of creole day laborers, while the Anglican parishes gave additional funds to almshouses to support refugees. The aim was to uplift the downtrodden so that they might integrate into society, effectively making them creoles and bolstering the minority white population. But no meaningful and effective strategy was deployed to economically integrate the refugees. Thus, the initiative to make creoles out of American Loyalists was unsuccessful.

The Assembly incentivized wealthier Loyalists to integrate into creole society by awarding tax exemptions to those intending to settle long term. This policy helped Loyalist slaveowners to pivot from the lowly status of refugees to entrepreneurial migrants. Policymakers also provided land grants to facilitate their integration into the plantation complex. The task of integrating Loyalists into this rigid slave society was easier said than done, however. The planter class was a closed world unto itself, and little arable land was uncultivated on the island. A plantation required large investments of capital, labor, and expertise, which very few refugees possessed. An ambitious project was put forward to deed lots in the parish of St. Elizabeth to Loyalists. But Jamaican officials jettisoned the project once the mangroves proved too thick for plantation agriculture.[17] Aspiring planters also buckled under the constant pressure of tropical heat, insects, disease, and dangerous reptiles. The Loyalist-owned Blacks brought to the island also struggled to adjust to the kind of labor expected on plantations. The rigors of rice and indigo agriculture in the Deep South did not prepare the enslaved refugees for the ravages of daily life on the island.

Conclusion

The people exiled in 1783 found themselves in a shifting empire that at various times treated them as deserving refugees, semi-free migrants, and pawns of imperial expansion. From the view of the Jamaican government, the earliest attempt at a social welfare system was an enormous and unwieldy public burden. The Loyalist refugees revealed the deadly faults that lay beneath the emerald veneer of the richest colony in the empire. Already overburdened by hurricanes, war debt, food shortages, and commercial regulations, Loyalist refugees added yet another heavy load. No other episode of the Loyalist diaspora as effectively captures the impact of Loyalist refugees on a host society than that of Jamaica.

The Loyalist problem soon presented the colonial government with few options. The expense of housing and paying stipends drained the parish coffers. In 1784, the Assembly recognized that it was cheaper to pay refugees to leave than it was to subsidize their stay.[18] However, Loyalists could not return “home” after 1783. The new republic made no meaningful attempt to repatriate the former colonists. There were significant reasons for not repatriating Loyalists—many rebels, including leading officials, received Loyalist-owned lands, estates, and enslaved property seized under the Confiscation Acts. An attempt to repatriate Loyalists would conceivably require that confiscated property be returned to them. Such a move would be deeply unpopular in the new nation, especially among recipients of spoils of war.[19]

The troubles in the British Caribbean continued after the Revolutionary War. The rhetoric of the American Revolution inspired oppressed peoples around the world to revolt. In particular, the long revolution in San Domingue in the 1790s sent tidal waves of fear through Caribbean slave societies. In response to a mistaken belief that newly arrived African captives sparked the revolt, Parliament restricted and ultimately closed the Atlantic slave trade in 1808.[20] The government abolished the trade because it presented an overwhelming security concern and threatened the production and transportation of sugar. Due in large part to the influential planter lobby, Jamaica maintained the balance of paternal security and enslaved production for several more decades. The British Empire did not unilaterally abolish slavery until 1834.

[1]John Eardley Wilmot, Historical View of the Commission for Enquiring into the Losses, Services, and claims of the American Loyalists(London: J. Nicholas, Son, and Bentley, 1815), 6.

[2]Jack Greene, “Liberty, Slavery, and the Transformation of British Identity in the Eighteenth-Century West Indies,” in Jack Greene, ed., Creating the British Atlantic: Essays on Transplantation, Adoption, and Continuity (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 303. Greene also treats the identity controversy at length in “The Jamaica Privilege Controversy, 1764-66: An Episode in the Process of Constitutional Definition in the Early Modern British Empire,”Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History Vol. 22 (1994): 16-53.

[3]An exploration of the rights and privileges bestowed on British subjects reveals that this blanket of universal rights was a fiction. Freeborn white men received full legal recognition by the state. But women, indentured servants, bondmen, and colonial subjects received fewer or no rights at all. Greene, “Liberty, Slavery, and the Transformation,” 294.

[4]Robert Zetter, “More Labels, Fewer Refugees: Making and Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalisation,” Journal of Refugee Studies Vol. 20, No. 2: 174.

[5]Ruma Chopra, Choosing Sides: Loyalists in Revolutionary America (New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2017), 14.

[6]Douglas Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 3.

[7]Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775-1782 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2009), 10.

[8]Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Random House, 2011), 270-1.

[9]Clement Gayle, George Liele: Pioneer Missionary to Jamaica (Kingston: Jamaica Baptist Union, 1982), 19.

[10]The Case and Claim of the American Loyalists, Impartially Sated and Considered, Printed by Order of their Agents (London, 1783), quoted in Jananoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 121-22.

[11]Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 121.

[12]Kristin Yarris and Heide Castaneda, “Discourses of Displacement and Deservingness: Interrogating Distinctions between “Economic” and “Forced” Migration,”International Migration Vol. 53, no. 3 (2015), 55-6.

[13]See Janice Potter-MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993) for an in-depth analysis of Loyalist refugee women’s means of navigating the paternalism of the Loyalist Claims Commission.

[14]See Stephanie Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019) for a synopsis of women’s commitments to slavery in the Antebellum South. Her study of white slave-owning women in the early to mid- nineteenth century parallels many of the commitments of women slaveowners in the Revolutionary era.

[15]Graham Hodges, The Black Loyalist Directory: African Americans in Exile after the Revolution (New York: Garland, 1996).

[16]Katy Long, “When Refugees Stopped Being Migrants: Movement, Labour and Humanitarian Protection,” Migration Studies Vol. 1, No. 1 (2013), 7.

[17]Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 258.

[18]Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 261.

[19]Codified into international law, namely via the 1951 United Nations Convention of the Status of Refugees and the subsequent 1967 Protocol.

[20]Christer Petley, “Slaveholders and revolution: the Jamaican planter class, British imperial politics, and the ending of the slave trade, 1775-1897,” Slavery and Abolition Vol. 39, No. 1 (2018): 58-59.

15 Comments

Georgia’s governor was James Wright, not William.

Not all Loyalists were slaveowners, not all Patriots were slaveowners. The right to self-government is what caused the revolution. The colonies had had their own charters since their foundation. When Parliament in London began gradually reducing the colonies’ ability to self-govern, that’s when discontent began spreading among Americans. The Crown never made mention of abolishing slavery or property rights. Also, the Americans petitioned the King twice, the first time asking to remove the Intolerable Acts (1774), the second time trying to avoid conflict (Olive Branch Petition, July 1775). They did so because their feud was with Parliament, not George III. The vast majority of colonists still considered themselves as Birtish subjects, loyal to the king.

The idea of independence became popular after George III declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion (August 1775), meaning all ties with the Empire were now gone.

Slavery played no role in leading up to the revolution. It rather played a role during the revolution – when people were exposed to the contradiction of fighting for natural rights and self-government, while holding others in bondage – reason why many Americans, like Washington, changed their views on slavery during the revolution; and also why Northern and central States either abolished the institution or passed laws leading to gradual emancipation, right after the end of the war.

The claim that slavery was a factor that sparked the revolution is backed by no proof. All contemporary documents make no mention of slavery, they only point out Parliament’s intrusion in local governments (mainly the imposition of taxes).

As usual with JARA, this is a thought provoking article. I read Mssr. Brady’s point that slavery underpinned so much of the Southern economy, that slaveholder economic self interest played large role in which side (Rebel or Loyalist) they thought would best protect that institution. As much as we (should) celebrate self determination and the philosophical basis of war, I’d suspect it’s day to day, economic survival that drives majority of behaviour.

Still doesn’t explain how slaveowners in the South felt like the institution was being threatened by the Crown or the rebels. Considering slaveowners and abolitionists were on both sides, the claim that the preservation of slavery led to the Revolution makes no sense.

If Virginians and Marylanders felt like slavery was being threatened by the philosophical ideology of New England, why did they join the North in the first place by sending regulars to fight Gage’s troops?

The colonies were not supposed to become a country after the war. The Articles of Confederation gave little to no power to the Continental Congress, considering the colonies as sovereign states – pretty much like the European Union.

What does that mean? It means that regardless of what Massachusetts thought of slavery, Carolinians couldn’t care less.

So one might think the colonists perceived the Crown as a threat to slavery. But then again, why? And why were so many slaveowners loyalists? Why does the petition of 1774 make no mention of slavery?

“Filled with sentiments of duty to your majesty and affection to the parent state, deeply impressed by

our education and strongly confirmed by our reason, and anxious to evince the sincerity of these

dispositions, we present this petition only to obtain redress of grievances and relief from fears and

jealousies [suspicions], occasioned by the system of statutes and regulations adopted since the close of the

late war for raising a revenue in America, extending the power of courts of Admiralty and ViceAdmiralty, trying persons in Great Britain for offenses

alleged to be committed in America, affecting the province

of Massachusetts Bay, and altering the government, and

extending the limits of Quebec by the abolition of which

system the harmony between Great Britain and these

colonies, so necessary to the happiness of both, and so

ardently desired by the latter, and usual intercourses, will

be immediately restored.”(https://americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/crisis/text7/petitionkinggeorge3.pdf)

This was written by slaveowners. If they thought Britain posed a threat to slavery, don’t you think they would have questioned the British and/or the King about their intentions? Don’t you think that AT LEAST a colonist would have reported that in his/her diary/letter/document/pamphlet/newspaper? There are plenty of such accusatory writings dating back to pre-Civil War America (Confederates trying to make an argument for the preservation of slavery), guess why similar writings do not exist for revolutionary America…

This whole revisionist narrative is completely ahistorical. It can’t be proven. It’s pure speculation. It’s the equivalent of saying that George Washington was a homosexual because he spent most of his time with Billy Lee or that Thomas Jefferson was a Muslim because he read the Qur’an.

The blanket claim that “this whole revisionist narrative is completely ahistorical,” demonstrates a a lack of engagement with the literature. Your question about why colonists from Maryland and Virginia would join New Englanders in their Revolution suggests the same.

When the war began in 1775, New England was not an abolitionist society or even on the road to abolition. Newport RI, Marblehead, MA, and Boston were all home to sizable enslaved populations. A crucial moment in VA’s revolutionary story—and by extension the narrative of the broader South—was Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation in November 1775 that promised freedom to enslaved people who escaped their rebellious masters and fled to the British lines. This executive order, if you will, galvanized southern planters who had revolutionary sympathies. It’s exactly why Jefferson’s final grievance in the Declaration of Independence begins, “He [the King] has excited domestic insurrections amongst us.” The domestic insurrection Jefferson referenced is Dunmore’s Proclamation which upended the system of slavery in the region, the very backbone of BOTH the South’s economy and social order. The point is that the commonality of slaveholding helped unite both northern and southern colonies against an empire that many colonists feared (rightly I might add) would abolish slavery in the near future.

“This revisionist history” doesn’t suggest defense of slavery was the sole cause of the American Revolution, but the evidence does reveal it played a crucial role.

So the executive order galvanized SOME planters? What about the rest? The loyalist ones. Again, you answered none of my questions.

No society was abolitionist prior to the revolution, that applied to both colonial society and British society.

“..an empire colonists feared (rightly I might add) would abolish slavery” what does that even mean? How do you come up with such stuff? Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania took up arms BEFORE the Dunmore’s Proclamation.

Patrick Henry (a slaveowner) did not declare “Give me liberty, or give me death!” because the British threatened to size his slaves.

Delegates did not come up together in the First & Second Continental Congress because the Brits were ending slavery throughout the colonies.

On the contrary, Dunmore’s Proclamation should have ended the revolution (at least in Virginia) by instilling a fear of widespread slave insurrections.

Colonists feared revolts, not the abolition of slavery.

Jefferson’s later writings demonstrate that; he feared something like the Haitian Revolution would happen in Virginia, he did not fear abolition, he advocated abolition.

As you said, slavery was the bulk of the South’s economy and social order, so why would the British want to ban the source of income of the territories they’re trying to retake? Make it make sense.

“Lack of engagement with the literature” I actually read the 1619 Project and other revisionist works. They all lack historical accuracy. Fan Fiction basically..

Have you seen a Chevron commercial? You’d think that their main product was wind farms. No Americans in the 1770s were FOR slavery, but many depended upon it completely for their livelihoods. Lord Mansfield’s 1772 decision against slavery in the Somerset case was viewed as an existential threat. If you want to see what British slaveholders thought with the rhetoric of liberty off the table, look at Edward Long’s History of Jamaica of 1773—a source for Jefferson’s infamous attack on Blacks in Notes on Virginia.

Lord Mansfield’s 1772 ruling in the Somersett’s case had no effects on the institution itself, it only made it illegal to transport a slave out of England against his will.

Although slaveowners in the New World must not have been happy with the ruling, they had no reason to think slavery was going to be abolished.

Without mentioning the fact that the First Continental Congress met two years after Mansfield’s decision and the delegates made absolutely no mention about the case when petitioning the King about their grievances.

You lumped together at one point Jamaica and Trinidad as needing protection by the Royal Navy against attack by other countries. Trinidad was a Spanish colony at this time, and was not captured by the British until 1802, so you should not have mentioned Trinidad in that context. Barbados, Antigua, and Saint Kitts were the next most valuable British Caribbean islands, and there were many other British islands to occupy the attention of the Royal Navy against aggression.

Interesting article, but the British refugees in Jamaica weren’t refugees because they were slave-owners, they were refugees because they were Loyalists. Being a slave-owner was certainly no reason to flee post war America, as even George Washington continued to own slaves until the day he died. So being a Loyalist was a cause to flee post war America, whereas being a slave-owner was not.

Interesting article. A few quibbles:

1) I think you’re mistaken in your point about Loyalist women and petitioning in the LCC. You state, “Women comprised the majority of claimants”; however, as Mary Beth Norton explains in her WMQ article from 1976, “Among the 3,225 loyalists who presented claims to the British government after the war were 468 American refugee women.” This is certainly a very clear minority.

You cite Janice Potter-MacKinnon’s “While the Women Only Wept,” which focuses exclusively on refugees in what would become Ontario. So perhaps the number of women petitioners is higher in Ontario than elsewhere—which certainly seems possible considering that, as Mackinnon explains, many wives fled without husbands. However, this was certainly not the case of refugee populations elsewhere, especially in the Caribbean where, as Jasanoff documents, the majority of white refugees traveled in family groups.

2) In your conclusion you note, “No other episode of the Loyalist diaspora as effectively captures the impact of Loyalist refugees on a host society than that of Jamaica.” I do not think this true. Certainly the refugees to Atlantic Canada, who represent more than half of the overall diaspora, had the most dramatic effect. After all, it’s only in Atlantic Canada that you see an entirely new colony (New Brunswick) formed from the arrival of refugees.

I actually think your study on the Loyalists in Jamaica is valuable because it demonstrates how SIMILAR the experiences of very different refugee groups were; that is, despite the tremendous differences between the Jamaican Loyalists and the Loyalists in Nova Scotia, they both overburdened the government, disrupted local politics, and were left unhappy with their situation. I think the only real outlier to this story are the Loyalists who went to Britain.

I think Patrick deserves praise for raising an awkward and contentious topic. The debate over slavery during the Revolution and its aftermath is bound to be antagonistic. (As can be seen from the blowback below.) I admire young writers’ who take on thorny issues like this and I hope the author will take my criticisms of his piece in the constructive way they are meant. As a British Historian, I only address those issues that relate to my countrymen in the piece.

1 “The centrality of slavery …shaped British strategy in the South. For reasons already discussed, the British supported the institution to prevent further rebellion and maintain the loyalty of the slave-owning class. “

This is simply untrue. It is debatable whether ”slavery” played any part in Germaine or Clinton’s original decision to invade South Carolina. However, what is undeniable is once there, the British did more to undermine the institution than support it. Clintons memorandum of June 3, 1780, three weeks after the British captured Charleston, instructed: “no Negroes shall be returned to his Master or Mistress, till such time as he or she shall have promised in the presence of the Negro not to punish him for past Offences.” This was astonishing enough. But he added if abuse took place, owners would “forfeit their Claim to the Negro.” The last British C-in -C sir Guy Carleton steadfastly refused to strip black refugees of their liberty, insisting, “Delivering up the Negroes to their former masters would be delivering them up . . . to execution and others to punishments which would . . . be a dishonorable violation of the public faith.” This directly defied article Article 7 of the Treaty of Paris, which read “ His Brittanic Majesty shall [withdraw] with all convenient speed, and without causing any Destruction, or carrying away any Negroes or other Property of the American inhabitants.” This is hardly a ringing endorsement of either slavery as an institution or tacit support for those who upheld it.

2 “Most free Blacks held no loyalty to the King-in-Parliament, they simply desired to maintain their status as free people.”

Debatable. Slaves greeted the British approach with joy, equating a scarlet coat with freedom. They were entirely reliant on the resolution of the British for their continued freedom. A South Carolinian runaway slave, Boston King, recounted, “To escape . . . cruelty, I determined to go to Charles Town, and throw myself into the hands of the English. They received me readily, and I began to feel the happiness, liberty, of which I knew nothing before.” At the surrender of Yorktown, Cornwallis arranged for several slaves to evade capture by transporting them on the sloop Bonetta to New York. These men all received small stipends or pensions at the war’s end. We have examples of their continued loyalty to the British long after the war ended.

3” Men often had their womenfolk submit petitions for the family, believing that paternalistic officials would reward women refugees with more generous allotments. The gendered aspect of claims also spoke to women’s commitments to slavery.”

I doubt it. I think you are reading far too much into this. Men submitted most petitions. It was not until 1802, that a Convention was formed between the British and American governments, to settle compensation claims. Is it not more likely that claims submitted by women were by widows rather than it being a ruse to arouse sympathy from a bureaucrat department of Government? That women signed petitions for compensation speaks more about their post-war financial hardships than it does to any “commitment to slavery. “

4 “The government abolished the trade because it presented an overwhelming security concern and threatened the production and transportation of sugar.”

Hardly. The 1807 Slave Trade Abolition bill debate in Parliament doesn’t even mention this as a factor. Lord Grenville gave the reasons behind British abolition best in this very debate. “ Was it, therefore, a trade which was in itself lovely and amiable, instead of being… wicked, criminal, and detestable, this would be an unanswerable argument for its abolition, …when it is considered that this trade is the most criminal that any country can be engaged in; when it is considered how much guilt has been incurred in carrying it on, in tearing the unhappy Africans by thousands and tens of thousands, from their families, their friends, their connections, and their social ties, and dooming them to a life of slavery and misery, and after incurring all this guilt, that the continuance of the criminal traffic must end in the ruin of the planters in your islands, who vainly expect profit from it, surely there can be no doubt that this detestable trade ought at once to be abolished.” These are humanitarian arguments, not economic-political ones.

5 “An examination into the priorities of Loyalists shows that most subjects cared more about their family and property than about the sovereign father, King George III.”

Probably. But could we not say this of any group of people holding a political ideal? Could you not argue that most Patriots “cared more about their family and property than about the Congress or George Washington.?” I think it simplistic to suggest Loyalists were unique in this priority.

“In the colonial mind, the right to liberty was synonymous with property ownership.”

This statement is somewhat misleading. While it’s certainly the case with powerful colonists, i.e., those who owned property (land and person) that liberty, in some ways, meant property ownership, this does not speak to the individual Americans who did not own property who saw liberty as something tangible. Among both wealthy and poor Americans, representation or the lack thereof in London, was the rallying cry for a reason. Yes, why representation mattered certainly cut in different ways depending on the person’s class status. But the benefactor of ‘liberty’ was not inherent to owning property.

One of the conflicts the Revolution unleashed was what liberty meant to the individual. For many of the founders, liberty did mean retaining special interests for themselves at the expense of granting it to everyone (one reason why democracy was feared by many of them). For others, particularly poorer Americans without property, liberty unleashed the individual’s identity and his/her rights, long gestating in English common law and colonial society prior to the 1760s. Coupled with the Enlightenment’s shift to early Romanticism’s distrust of ‘established norms,’ liberty not only helped define the interests of the elite during the American Revolution, but it also became the symbolism by which any American could benefit from. This is why the abolitionist and early suffragist movements gained legitimacy and traction in the 1780s immediately after the Revolution. “Liberty for thee but not for me?”

The question is whether liberty was meant for everyone or specific individuals. When stated “the right to liberty,” then yes, property ownership accounted for this privilege of ‘rights.’ But liberty was not something that could be contained to just those who owned property. Why else would Thomas Jefferson, champion of the Enlightenment, early Romantic, slaveowner, and author of the Declaration, endorse the French Revolution and early on write of the promise of “the people” rising up for liberty in the face of tyranny? Was it in the hopes of the peasants becoming property owners or in the chance of the peasants obtaining individual liberty? Even here, someone like Jefferson may serve as a contradiction. The Founders themselves were evolving and some were suspicious of what liberty meant and where it could go. Evoking that mindset, one understands that liberty meant different things to different people. It wasn’t wealthy slaveowners who held demonstrations around the Liberty Tree in Boston, nor was it poor artisans justifying freeing their slaves because the ‘peculiar institution’ was incompatible with the principles (liberty) of the American Revolution.

The letters of a Loyalist who later moved to Jamaica and lived out his life there is “A Georgia Loyalist’s Perspective on the American Revolution: The Letters of Thomas Taylor” GEORGIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY 81 (Spring 1997): 118-38. Taylor filed separate claims for his losses in Georgia and in East Florida.

Were not Liele’s followers responsible for Jamaica’s Baptist War in 1833 that came just before Great Britain freeing all slaves in its Empire?