Thomas Read (1740-1788) of New Castle, Delaware, as we read in the first part of this series, began his seafaring career as a merchant captain, sailing for the Philadelphia firm of Willing and Morris in the ship Aurora, alongside his friend John Barry in Black Prince. After fighting had erupted around Boston, in May 1775 the firm took what would be the last opportunity to trade with Britain. The two sailed in May, arrived in June, and were the last two ships to leave London on August 11, arriving in Philadelphia on October 5 and 6, respectively. They brought the news from England that caused the Second Continental Congress to take the first cautious steps toward creating the Continental navy.[1] Having made that contribution, Captain Read visited the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety and volunteered his services, to the Pennsylvania navy, which was already forming.

On July 18, the congress had resolved that

each colony, at their own expence, make such provisions by armed vessels or otherwise . . . for the protection of their harbors and navigation on their coasts against all unlawful invasions, attacks and depredations, from cutters and ships of war.[2]

The Pennsylvania Committee of Safety understood that it would be their responsibility to defend the largest city and main seaport of the colonies and the meeting place of the Congress. They had already received the advice that “the only effectual opposition that can be made to ships of force, is by ships of force.”[3]

Accordingly, the committee established a sub-committee for the construction of boats and machines to begin building a force that would become the Pennsylvania navy. On July 7, that group ordered the design of an armed galley from the shipyard of Wharton and Humphreys, of which Joshua Humphreys, age twenty-one, was the operating partner. The design was delivered the next day and the vessel was delivered on July 19. It was called L’Experiment, suggesting it was the first step in Humphreys’ future career as a ship designer.

By early October, when Read offered his services to the committee of safety, construction of thirteen galleys or gondolas already had been completed from a variety of Philadelphia shipyards. These were variations on Humphrey’s design, about fifty foot length, broad of beam, and shallow draft, with twenty banks of oars and two short masts for lateen sails.[4] They had an eighteen- or twenty-four-pound gun in the bow and smaller armament. All had been commissioned. Captains had been appointed. During October, officers were being selected and the boats were being armed and provisioned.[5]

The committee had asked the Pennsylvania Assembly for permission to name a commander-in chief or commodore for the growing navy. On October 20, the assembly resolved that such a commander was necessary and the committee should nominate a person considered qualified. The committee quickly responded that: “after full consideration of his Merits and enquiring into his character and Qualifications, [it was] Resolved that the said Capt. Thomas Read be appointed by the Honorable House of Assembly to that Important Position.” Based on that resolution, Thomas Read has gained recognition as “The First to Attain the Rank of Commodore in Command of an American Fleet.”[6]

The “fleet” that Read would command approached forty vessels within a year. In addition to the thirteen galleys or gondolas, there were twenty-one smaller single-masted armed boats or guard boats, plus fire ships, floating batteries and other types ordered and under construction. Most important to Read was the intention of the committee “to determine if a Ship can be bought, fit for a Provincial Ship of War.” It turned out that no suitable ship was found for purchase. The shipyard of Simon Sherock received a contract to build the ship. Capt. John Barry is said to have superintended the construction as he had supervised the first ships of the Continental navy.[7]

Unfortunately, Read was never formally appointed as commodore. There is no evidence that the committee forwarded his name to the assembly. Upon receiving word of the resolution and pending appointment, the thirteen captains of the galleys wrote a long, obsequious, and complaining “memorial” to the committee. Essentially, they “were in the hopes that the eldest Captain would be appointed to the command . . . to be succeeded by the next eldest.”[8]

There is no evidence that the committee considered this memorial, nor did they have to, at least for a while. The instructions to the captains, already published, stated that “The Eldest officer present, when more boats are together than one [is] to act as Commodore and have Command of the whole.”[9] Since the thirteen galleys were the only operational force at the time, this placated the galley commanders. As the force grew with the completion of ten fire rafts, and more building, Capt. John Hazelwood took command of them. Finally, on January 13, 1776, Capt. Andrew Caldwell, an aged and infirm officer, was appointed as commodore of the navy.[10] In March the committee resolved to appoint Read “second in command” and captain of the ship under construction. That was the fourteen-gun frigate, largest ship of the fleet, Montgomery.[11]

In addition to building ships, the committee had been busy directing completion of a number of other defensive measures. The former British fort on Fort Island (also called Mud Island, Liberty Island and later named Fort Mifflin) was rehabilitated. A number of chevaux de frise were sunk to obstruct the channels, and the number of pilots who could take ships past these obstructions was limited. [12]

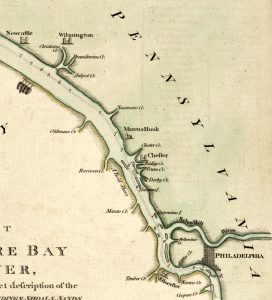

Henry Fisher, a senior pilot at Lewes on Cape Henlopen, was appointed to warn the committee of any British warships arriving at Cape Henlopen and intending to move north. Soon Fisher recruited men to establish a warning system of thirteen stations from the Cape Henlopen Lighthouse to Philadelphia. The stations were equipped with horses, boats and cannons provided by the committee of safety to relay messages by established signals between the cape and Philadelphia. That effort was supervised by a sub-committee which included Thomas Read.[13]

Fisher’s first message was on March 25, 1776 to report the arrival of the British forty-four-gun ship Roebuck commanded by Capt. Andrew Snape Hammond. Over the next several days Hamond established a blockading force at the cape. That provided the Pennsylvania navy with its first opportunity for naval combat. On April the 29, Read received orders:

the Roebuck Man of War is aground upon Bra[n]dywine [Shoal] you are directed to proceed with the province Ship Montgomery under your Command and proceed down the river and Bay and join the Commodore who is already on his Way with the armed Boats to take or destroy her . . . not a Moment must be lost and it is expected that you will obey this Order immediately upon the first of the Ebb.

Unfortunately, his ship was still fitting out and the crew totaled only about twenty, including officers. Guns and crew had to be taken aboard from the artillery barge Arnold and the rest of the crew made up of volunteers from the Pennsylvania militia serving as seamen. Accomplishing that in the driving rain delayed sailing. Fortunately so. The commodore who had been down to observe the situation returned with the information that Roebuck was off the shoal. As one of Read’s volunteers, Charles Biddle, a Philadelphia socialite, commented pessimistically but accurately: “Had Captain [Hamond] kept his ship on a heel [thereby elevating his guns for a broadside] near the shoal, he could easily have taken the ship.”[14]

On May 5, Fisher had occasion to send an urgent message to Port Penn and to the committee in Philadelphia. The Roebuck, along with the twenty-eight-gun frigate Liverpool and a sloop tender Betsy, was proceeding up the bay.[15] Capt. Charles Alexander in the Continental sloop Wasp, who had been patrolling the southern bay, also ran north ahead of the British, alerting Port Penn and Chester, Pennsylvania, before entering the Christiana River at Wilmington, Delaware. The British ships moved slowly north in poor weather, sounding the channel.[16] They arrived north of Wilmington on the 7th.[17]

The Fisher warning had been received by the committee early on the 6th. The committee called the officers and men of the navy in town to man their galleys, which were moored at Fort Island, and had Captain Hazelwood send his fire ships there.[18] On the 7th, the committee ordered Read to order the thirteen galleys under Captain Henry Dougherty to proceed down the river and prepare to “attack, take, sink, destroy, or drive off” the British. They also ordered down the Fire sloop under captain Gamble, assuring the crew that their dangerous duty would be rewarded handsomely. The committee ordered provisions and cartridges sent down on the supply shallop.[19]

The order was sent to Read aboard Montgomery at Fort Island. The commodore was in Philadelphia and ill. Read convened a council of war with the captains. All but one reported that their boats were undermanned, well below their fifty-man complements, some as low as twenty-two. Read ordered his 58 man marine detachment, plus 74 men from the crew of the floating battery Arnold and the 119 man Fort Island artillery company to fill out the depleted crews to almost full strength. He ordered his 3rd lieutenant to take a boat and volunteers from Montgomery to help Captain Gamble maneuver the fire sloop. Read obtained several pilot boats to maneuver the fire rafts, which remained at Fort Island.[20] By agreement between the committee and Congress, Read met with Capt. Lambert Wickes of the Continental brig Reprisal and obtained officers, sailors, and marines for those boats. Acting for the marine committee of Congress, Robert Morris also ordered Capt. John Barry to join Read at the chevaux-de-frise and to provide as many crew as he needed for Montgomery.[21]

In addition to receiving undermanned boats, Read found that ammunition was in short supply. The galleys were to have fifty rounds and only had twenty-eight. Read distributed all but six rounds per gun of Montgomery’s and all of the floating battery Arnold’s, which remained at Fort Island.

Undertaking all this, Read was becoming “exited and irritable . . . The frustrations of commanding a fleet so devoid of equipment to face frigates would have discouraged and upset men of greater experience than Read . . . These annoyances were enough to thwart any commander, but the greatest vexation would be meddling by the Committee of Safety.”[22]

After sending Read his orders, later in the day the committee met again. They appointed a four-man subcommittee to proceed to Fort Island in the province sloop. They were given “full and ample power to enforce such orders as have already been issued, or may be issued from this Board, to the Commanding officer of the Naval armament of this Province.” [23] Clearly, Read was denied overall command of the forces or direction of the battle to come.

Read sent a report of all the preparations he had taken and reported that the “Gentlemen” who were to be his overseers had arrived. Late on May 7, Read and Dougherty met with the sub-committee who confirmed the earlier orders. Dougherty was ordered to take thirteen galleys and the fire sloop down river to meet the enemy. The subcommittee took up position to the rear of the galley force. The now undermanned and virtually disarmed Montgomery and floating battery Arnold were to go down behind the chevaux-de-frise along with the continental ship Reprisal.[24] Stationed well to the east of the engagement, presumably, the committee considered them a reserve force, in the unlikely event the British tried to pass the channel obstructions and attack Fort Island. For the next two days Read would serve as quartermaster, scraping together men and decent supplies. [25]

The morning of the 8th was breezy and hazy turning to calm and fog. The British were still just north of Wilmington. As the weather cleared, after noon, the galleys moved in to attack. The British, who had not been expecting an attack, had to set sails, clear for action, and come to broadside position. This began a two-day battle. The banks of the river from Chester to Wilmington were lined with spectators.[26]

There were many descriptions of the two-day battle, often in disagreement with each other.[27] The most succinct description and the most important to the navy was from Robert Morris, vice president and active leader of the committee of safety as well as the Continental naval committee’s leading member. He wrote:

the Men of Warr have given us an opportunity of trying the use of our Galleys or Gondola’s, the Roebuck of 44 Guns & Liverpool of 28 Guns came up the River opposite to Wilmington Creek for fresh Water, our little fleet checked them there but not knowing their own strength or not having sufficient Confidence in it, they kept at too great a distance the first day . . . They drove the Roebuck on shore [aground the first night] & with good management might have taken her . . . The second [day] they begun to know themselves a little better and attacked them again very smartly] they greatly damaged that Ship & obliged both her & the Liverpool to push back . . . leaving behind them a Transport Brigt [Betsey] which our People [Capt. Alexander in Wasp] took from them.[28]

As Morris noted, the attack of the first day did little damage but caused Roebuck to maneuverand run aground. She was stuck and heeled over the first night. At that point, the galleys or the fire sloop might have attacked. That observation was widespread among spectators and the lack of action was criticized in the press.[29] More pertinent was the critique of seventeen-year-old Joshua Barney, 1st lieutenant of Wasp and future captain and hero of the Continental navy, Pennsylvania Navy, and United States Navy:

some of the gallies could not come into action for want of men, I volunteered with a number of our men & went on board one of them, when she was rowed up to the enemy the action became warm & the Enemy were drove down before us as low at New Castle. Much might be said respecting this action, it was generally believed that the Roebuck might have been destroyed whilest aground in the night by our fire vessels, but no attempt was made; the blame laid between the Commodore and Committee of Safety, but I am of the opinion that the latter were in fault.[30]

He was right. It was the committee that had chosen to direct the action and its subcommittee that should have advised them of the situation.

Because of the public criticism, one week after the battle, the captains of the galleys published an open letter expressing their dissatisfaction with the support provided by the committee of safety, especially ammunition, and stating “at the time the Roebuck got aground otherwise, we have every reason to believe we should have made a prize of her, as we had above an hour’s daylight when we were obliged to retreat for want of ammunition.”[31] The committee asked the assembly to investigate.[32]

On May 11, Read in Montgomery and some galleys were still down the river in defensive positions. Anticipating, or perhaps hoping for, action, Read was still trying to get his ship in fighting condition. He complained to the committee of the lack of anchors for the galleys, unusable ammunition and, as to the volunteers sent down with Barry, “some method must be taken to get us Man’d, you may depend on it we can make no defence in the situation we are in. As for Volunteer[s], I will not be in the Ship with them, they know nothing, and will do nothing they are ordered.[33]

On May 25, Commodore Caldwell resigned his position because he was, “Confined to my bed by a severe Illness.”[34] On the 29th the committee told Read that Caldwell had resigned and “The Chief command of the Fleet, consequently, for the present devolves upon you.”[35]

Read was certainly not interested in dealing with the disputatious captains who had earlier protested his appointment as commodore, nor a committee that had pushed him aside from command, nor an investigation by an assembly committee to which he would have to testify, honestly, against the committee.[36] More importantly, he wanted an opportunity for naval combat. Thus, on June 6, Thomas Read asked the committee of safety to “Accept my Resignation of the Commission you were pleased to honour me with for the Ship Montgomery . . . this Request proceeds from a wish to be in a situation to take a more active part in the present Dispute between America & Great Britain.[37]

Read was originally given a Continental navy commission back-dated to April 6, 1776. That date was soon after he was denied the position as commodore and became second in command and assigned to Montgomery. It is also likely about the time when he first approached the marine committee for an appointment. He was placed eighth on the list of seniority.[38]

[1]William Manthorpe, “Thomas Read of Delaware, Part 1: The Creation of the Continental Navy,” Journal of the American Revolution, March 2, 2021.

[2]Continental Congress, “Resolution of July 18, 1775,” Journals of the Continental Congress Vol. II, 189, Library of Congress, memory.loc.gov/(JCC).

[3]“Lewis Nicola to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, July 6, 1775.” Naval Documents of the American Revolution1: 831, Naval History and Heritage Command, www.navy.history.mil(NDAR).

[4]John W. Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy, 1775-1781: The Defense of the Delaware (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1974), 13-18 and “Appendix A: The Fleet,”336.

[5]“Contemporary List of the Pennsylvania Row Galleys,” NDAR, 2: 428. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] Monday October 2nd,” NDAR, 2: 272. “Minutes of the Philadelphia Committee of Safety,” [Philadelphia] October 16th. NDAR, 2:480. “Military Stores & Ammunition to be Put on the Armed Gondolas, [Philadelphia, October 21, 1775,” NDAR, 2:560-564.

[6]“Journal of the Pennsylvania Assembly, [Philadelphia] Friday, October 20, 1775,” NDAR, 2:544. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] October 23, 1776,” NDAR, 2:581-582. That attribution is the caption on the lithograph from the only known portrait of Thomas Read. Unattributed. Probably by M. Armand Dumaresq after John Trumbull, in Harmon Pumpelly Read, Rossiana: Papers and Documents Relating to the History and Genealogy of the Ancient and Noble Family of ROSS . . . Together with the Descent of the Ancient and Historic Family of READ (Albany, NY: Press of the Argus Co., 1908), 281. Also in J. Thomas Scharf, History of Delaware: 1609-1888 (Philadelphia, PA: L. J. Richards & Co., 1888), Vol. 1, 188.

[7]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] November 3d,” NDAR, 2:873. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] November 7th,” NDAR, 2: 918. Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy, 25. William Bell Clark, Gallant John Barry, (New York: Macmillan, 1938), 71.

[8]“Memorandum of Captains of Pennsylvania Galleys,” NDAR, 2: 654.

[9]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] October 16th,” NDAR, 2:480.

[10]Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy, 19, 334.

[11]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, In Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] 6th March, 1776, NDAR, 4: 201-202.

[12]Re: Fort Island: “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, At a Meeting of the Committee at Fort Island, October 15th,” NDAR, 2:464. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] October 16th,” NDAR 2: 481-483. Re: Chevaux-de-Frise: Literally, “Frisian Horses,” originally an anti-cavalry barrier. These were strong timber poles secured to the bottom by a framework filled with rocks and protruding at an angle upwards to just beneath the surface of the bay. They were capped with sharp metal tips that could pierce the hull of any unwitting ship. They would have to be removed or destroyed by an approaching enemy squadron while under fire from the fort and the galleys of the Pennsylvania navy.“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] November 8th,” NDAR, 2:940. Re: Pilots: “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] October 20th,” NDAR, 2:544 and October 21st, NDAR, 2: 558. “Minutes of the Philadelphia Committee of Safety, [Philadelphia] November 7th,” NDAR, 2: 918-919.

[13]“Instructions of the Committee of Public Safety at Philadelphia to Mr. Henry Fisher at Lewistown,” NDAR, 2:122. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, In Committee of Safety. Philad’a, 20th Feb’y, 1776,” and “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” In Committee of Safety. Philad’a, 9th March, 1776,” NDAR4: 266. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, In Committee of Safety, Philad’a 15th March, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 354.

[14]“Pennsylvania Committee of Safety to Captain Thomas Read, In Committee of Safety [Philadelphia] April 29, 1776, 11 o’clock A. M.,” NDAR, 4: 1315. Charles Biddle described the whole affair in his autobiography. See Note 2 and James S. Biddle, ed., Autobiography of Charles Biddle . . . 1745-1821 (Philadelphia, 1883).

[15]“Henry Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Lewistown, May the 5th 1776,” NDAR, 4:1416.

[16]“Journal of H.M.S Roebuck, Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, May 1776. Saturday 4th, Sunday 5th, Monday 6th, Tuesday 7th,” NDAR, 4:1446-1447. “Journal of H.M.S. Liverpool, Captain Henry Bellew, May 1776, Sunday 5, Monday 6, Tuesday 7,” NDAR, 4: 1447.

[17]“John Mckinly [Governor of Delaware] to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Wilmington 2 o’clock PM. Tuesday 7th May, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 1446. “Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, [Roebuck, Delaware River] Tuesday, May 7, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1447.

[18]“Pennsylvania Evening Post, Tuesday, May 7, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1443. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, In Committee of Safety [Philadelphia] Monday 6th May,” NDAR, 4: 1425.

22“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Phil’a 7th May 1776,” NDAR, 4:1443-1444.

[20]“Amount of Men in Actual Pay, Officers included, in the Naval Service of the Province of Penn’a, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1366. The muster was dated May 1 and men were listed by ship. “Captain Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Ship Montgomery May 7th, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1445.

[21]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Phil’a 7th May 1776,” NDAR, 4: 1443-1444. “Marine Committee of the Continental Congress to Captain John Barry, Philad’a May 8, 1778,” NDAR, 4: 1463. Barry sent seventy of his crew aboard Hornet.

[22]Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy, 42-43.

[23]“At a special meeting of the Committee of Safety at ¼ after 5 o’clock, P.M., 7th May 1776,” NDAR, 4:1444.

[24]“Captain Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Ship Montgomery May 7th 1776,” NDAR,4: 1445-1446.

[25]Sample messages are “Captain Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, [Montgomery Delaware River] May 8, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1465. “Captain Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety” Ship Montgomery May 9th 1776 9 o’clock [A.M.],” NDAR 5: 16-17. “Captain Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Ship Montgomery May 9, 1776 3 o’clock [P.M.],” NDAR, 5:17.

[26]“Autobiography of Charles Biddle, [Philadelphia] May 8, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1465.

[27]Jackson describes the battle, The Pennsylvania Navy, 39-52. Jackson cites a wide variety of Pennsylvania observer reports of the battle found throughout NDAR Vols. 4 and 5 and in the Colonial Records of Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Archives and the Pennsylvania Division of Archives and Manuscripts. In a note to his description, he states, “The best detailed accounts of the action between the Pennsylvania and British ships Roebuck and Liverpool are in William B. Clark, Lambert Wickes (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1932), 20-35 and in Clark “The Battle of the Delaware,” New Jersey Society of Pennsylvania, Year Book, 1930 pp. 31-73.” British accounts of the first day of the battle are “Journal of H.M.S Roebuck, Captain Andrew Snape Hammond,Wednesday, 8th,. NDAR, 4:1470 and “Journal of H.M.S. Liverpool, Captain Henry Bellew, May, Wednesday, 8th,” NDAR, 4:1471. Accounts of the second day are: “Journal of H.M.S. Roebuck, Captain Andrew Snape Hamond. May 1776, Thursday 9th [4 AM GMT],” NDAR, 5:18-19; “Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, [May 5 to May 9, 1776],” NDAR, 5:16-17; “Journal of H.M.S. Roebuck, Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, May 1776, Friday 10th,” NDAR, 5: 105; “Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, [Roebuck, Delaware Bay, Wednesday May 15th],” NDAR 5: 109; “Journal of H.M.S. Liverpool, Captain Henry Bellew, May 1776, Thursday 9, in Delaware River,” NDAR, 5: 19. While the British reported little damage (“Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, [Roebuck Delaware River Wednesday, May 15],” NDAR, 5:109), a captive American aboard Roebuck later reported substantial damage to her (“Deposition of William Barry, [Newcastle] June 11, 1776,” NDAR, 5:481.

[28]Benjamin Franklin was president of the committee but rarely attended. “Robert Morris to Silas Deane Philad’a, June 6th 1776,” NDAR, 5: 308. The sentence marked by [. . .] was moved to reflect an accurate sequence of events.

[29]For example, “Pennsylvania Evening Post,Saturday May 11, 1776,” NDAR, 5:53.

[30]“Autobiography of Joshua Barney, May 9. 1776,” NDAR, 5: 17. Since this was written retrospectively, Barney may have known of the subsequent dispute between the captains and the committee. Read certainly would have agreed as his actions within the month demonstrated.

[31]“Pennsylvania Galley Captains to the Public, [Published in several Philadelphia newspapers],” NDAR, 5: 127-128.

[32]“Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, in Committee of Safety, 27th May 1776,” NDAR, 5:275.

[33]“Captain Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Ship Montgomery, May 11, 1776,” NDAR, 5:54-55. Clark,Gallant John Barry, 89.

[34]“Commodore Andrew Caldwell to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Philad’a May 25, 1776,” NDAR, 5:253.

[35]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, in Committee of Safety [Philadelphia 29th May, 1776,” NDAR, 5: 297.

[36]The captains also opposed the appointment of Caldwell’s successor, Capt. Samuel Davidson, until it was rescinded by the committee and the assembly then worked a compromise. Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy, 65-68.

[37]“Thomas Read to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, June 5, 1776,” NDAR, 5:384-386.

[38]“Officers of the Continental Navy and Marine Corps,” Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil.

One thought on “Thomas Read of Delaware, Part 2: Commodore in the Pennsylvania Navy”

The galleys had been ordered to fire only half-charges from the bow guns ostensibly to conserve ammunition. Unfortunately they engaged the Roebuck from too far a distance and most of the shot fell short. One possible thing the Committee might have known, but the crews of the galleys did not, was that most of their 18 and 24 pounders had recently been cast at the furnaces on the French Creek, and none of them had been properly proved. (Every time they tried to prove one by the prescribed method it burst.) So Rittenhouse (head of the committee to acquire arms) let them forgo this vital measure, or proved the guns with only a normal charge. Restricting the cannon to half-charges, then, might have been the result of their unreliable nature, rather than simply trying to conserve powder.