A New England Quaker in his late thirties was not the ideal candidate for the job, according to the Continental Congress. Instead, Congress chose Gen. Horatio Gates. Gen. George Washington dithered and dissented in his gentlemanly way with Congress, but to no avail. General Gates was appointed commander of the southern theatre of the War in 1780, but his command was short-lived. His defeat, at the hand of British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis in Camden, South Carolina, gave “The Fighting Quaker” a second chance. With Washington’s directive, the Continental Congress appointed Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene to command the southern army. The newly-minted commander had served as a general under Washington, gaining fighting experience when the British landed in New York in 1776. As the war expanded and logistics demands grew, Greene was shelved as a combat general and took on the underappreciated but extremely important position of Quarter-Master General of the Continental Army. Although it was a post he was suited for, Greene famously remarked that quarter-masters were forgotten to history.

The scholarly and bookish commander, now restored to a combat role, entered Charlotte on December 2, 1780 at the head of the Southern command. He sauntered into town only to discover a rag-tag army of irresponsible militia and sickly continental soldiers stationed around the courthouse. Many were ill with smallpox, starved, or enduring ailments brought on from the elements. The destitution of disease and lack of supplies brought the Southern army to a new low. The visual state of the men demonstrated the importance of previously-overlooked things. Greene took a quarter-master approach, and he acknowledged that, “the article of clothing is but a small part of the expense in raising, equipping, and subsisting an army, and yet on this alone the whole benefit of their service depends.”[1] Patriot hopes in the Southern Colonies were set on men who were simply trying to remain alive. Clothes and food were now the weapons of war and in fearfully short supply.

Greene took to this monumental task with immediacy. He dispatched a letter to Thomas Jefferson, governor of Virginia, depicting the situation.[2]

No man will think himself bound to fight the battles of a State that leaves him to perish for want of covering; nor can you inspire a soldier with the sentiment of pride whilst his situation renders him more an object of pity than envy. The life of a soldier in its best state is subject to innumerable hardships, but where they are aggravated by a want of provision and clothing his condition becomes intolerable, nor can men long contend with such complicated difficulties and distress,—deaths, desertion, and the hospital must soon swallow up an army under such circumstances and were it possible for them to maintain such a wretched existence, they could have no spirit to face their enemies, and would inevitably disgrace themselves and him who commanded them.

Greene was primarily concerned with maintaining a fighting core, but his self-esteem and pride played a noticeable role in his remarks to Jefferson. Reputation, both his and army’s, were on the line. The task at hand was far more challenging than anticipated. The cold-shock would not resolve itself easily. Greene wrote a month later in a similar tone, “when I left the northern world I expected to meet difficulties in this, but they multiplied infinitely beyond my apprehension. There is but barely the shadow of government remaining in this country.”[3] Not only had Greene’s view remained the same, but he increased his apprehension by the absence of a formidable or useful government. This was unlike anything he had seen in the North. The war placed such a burden on him, his supplies, his men, and his tactics that the difficulties felt nearly insurmountable.

The philosophy of the Southern war was different from the North. Civil war conditions were widespread, even exceeding the practices of formal larger-army combat. This inter-colonial combat between Tories and Whigs created supply chain problems and shortages, and Greene did not wish to call troops to muster, only to arrive at camp and be deflated by the state of the army. He understood that the ability to care for the army reflected on the colonial governments. If a new government, which men were fighting to liberate from the British, could not support them, then why support it? Greene wrote Washington despondently telling him he ordered, “the Board of War of this State [North Carolina] not to call out any more Militia until we can be better satisfied about the means of subsistence for the regular troops and the Militia.” Until Greene could rectify the supply lines, he could not support additional troops. He had mouths to feed and bodies to cloth aplenty.[4]

The first order of business was contacts. Greene wrote to General Gates, who still maintained a fledgling command, “I find myself much at a loss for information; and none of the papers you have left me are calculated to give the information I want.”[5] Greene also requested information regarding bills and their amounts, the names of those commissioned to purchase on behalf of the army, what mines lead came from, where it was delivered, for all names of Patriots on parole, and any local or regional maps.[6] Gates, who was not known for his organizational skills or forethought, evidently left things in disarray, and Greene was frustrated and troubled. His frustration circumnavigated the Patriot authorities, probably via Washington or Jefferson, because Greene received a letter in early December from John Matthews of the Continental Congress. As a member of the Committee to Correspond with the Commanding Officers of the Southern Department, his letter explained that he had received “reiterated information” of anticipated supplies for Greene and his men. Although vague, it was certainly a hopeful statement. Greene had not yet been worn down by wishful thinking and “anticipated” supplies.

A cold Carolina winter set Greene to the task of securing clothing for his men. Gunpowder was superseded by the need for fabric. On December 16, Greene wrote Joseph Marbury requesting clothes be made. Ahead of the letter’s dispatch, he sent “oznaburgs and sheeting” to be used in the making of the clothing.[7] Greene was experienced and level headed, but the frustration was mounting. In an uncharacteristic manner, Greene’s letter was forceful and demanding: “You will engage the women of the country to make them, and, if you cannot do better, they must be paid in salt. You know the distresses of the soldiery, and I flatter myself that you will make every exertion to have them made up immediately.”[8] Evident stress plagued his waking hours, making for a bleak Christmas. The Southern army was in a “shocking situation” and “indeed of the whole army” for want of “cloathing.”[9] However, Congress purchased a late Christmas present in the form of authorized acquisition of “woolen cloth and blankets.”[10] Despite that gift, the Southern Department persisted in its perilous state. The only thing Greene did not lack was anticipation and worn-out hope.

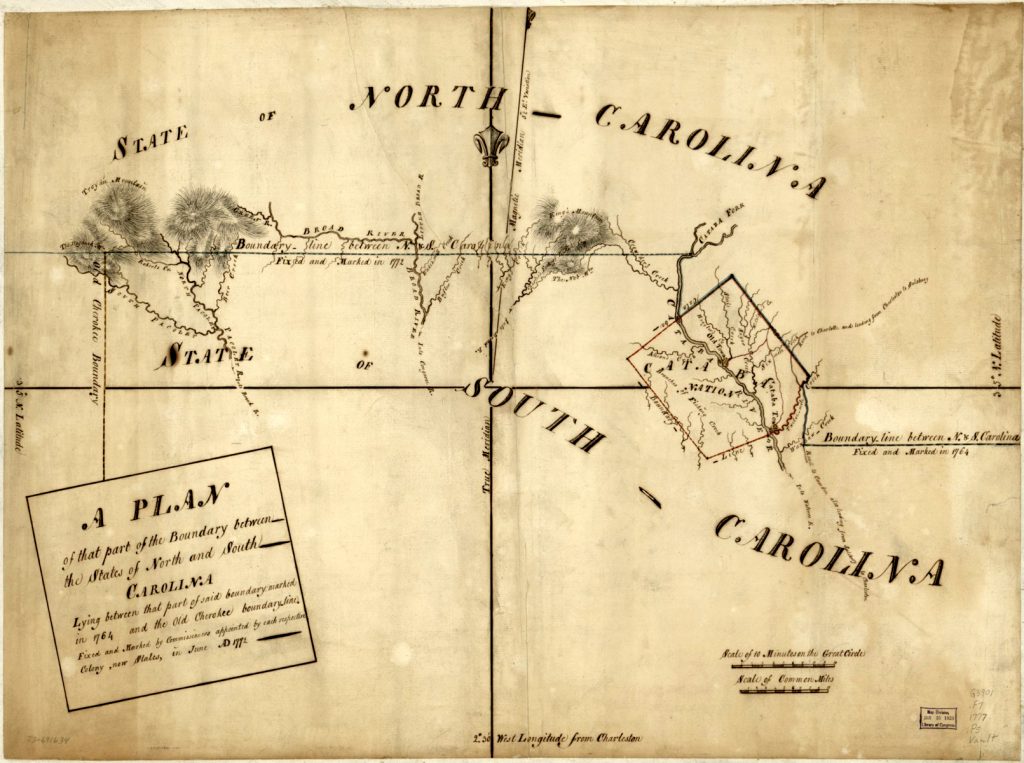

Congressional blankets, a command to have clothes made, and inquiry about the sources of other materials left Greene wanting. His work had come nearly to naught, certainly insufficient to ready an army for combat. He persisted and wrote Robert Rowan, commanding clothier-general of North Carolina, expressing his desperate need for, “clothing and shoes.” In the meantime, the necessity of clothes caused Greene to become more creative. His men had been able to kill “beeves [beef cattle] . . . for the use of the army afford a great number of hides, which I wish to have exchanged either for tanned leather or good shoes.”[11] The waterways of the Catawba and Peedee Rivers offered some game to kill and exchange. Two days later, Greene wrote again about animals in the region, this time informing General Washington that he had “to send . . . a corps of horse” and the Virginia Legion away, because, “both being unfit for duty for want of clothing and other equipment, and the difficulty of subsisting of them is much greater here than there.”[12] The same region that supplied cow hides was insufficient for horses. The Patriot army seemed to be going in circles on the edge of collapse. Even more determinedly, the lack of supplies now began to actively diminish the size and diversity of his army. Yet, Greene preserved.

To counter the imbalance of supplies. Greene decided to make a risky move. He informed Samuel Huntington of the Continental Congress that, “I made a detachment from the Army to operate on the West side of the Catawba under the command of General [Daniel] Morgan consisting of between 3 and 400 choosen Infantry.”[13] Greene remained south of Charlotte Courthouse, on the Peedee River in South Carolina, effectively on the border between North and South Carolina. A well-read military tactician, Greene knew he was adding peril to destitution. This one choice could crush the rebellion in the South. The British could move in and crush the divided, smaller patriot armies one at a time, but he had no choice. Greene was forced to risk his command and his men in order to allow foraging for food and supplies.

Although Morgan permitted his men to forage in the South Carolina countryside, the attempt to resolve the shortages came up empty handed. Instances of hope burst forth through letters Greene received; even if only short lived, they offered tangible enthusiasm. One such letter Greene received arrived on December 29. He told Morgan, “a large number of tents and hatchets are on the road. As soon as they arrive you shall be supplied. Many other articles necessary for this army, particularly shoes, are coming on.”[14] No doubt this bolstered the whole army, officers included. The hatchets would be useful tools, primarily for cutting firewood, while the tents would protect the naked and destitute soldiers from the frigid temperatures. If clothes could not be obtained in abundance, at least the men could be kept out of the weather conditions. The fight in the Southern Command rested on the acquisition of everyday items. Greene knew what history has long proven, the Romans had displayed, and the British knew thoroughly, a well-supplied army was the basis for a strong fighting force. The trickle of supplies, though largely insufficient, bolstered the mood of Greene’s army and propelled it forward, as spring arrived and the British mobilized for large army campaigns.

Money was also a problem. A lack of unified currency and inflation crippled the war effort and the North Carolina government. The colonial legislature’s ability to help and support Greene and Morgan was minimized without hard money. Inquiries and the insistence on paper money had produced little in the early days of 1781. Alexander Martin, a member of the North Carolina Board of War, informed Greene that “our Treasury is exhausted of Money, and will continue so until the Collection of the Money Tax.”[15] The collection was not likely to be overly successful or speedy, so the legislature at Halifax was not optimistic. Even a full coffer was hindered by shortages and broken supply chains. For Greene, no money was in sight or soon to come available. He was forced to encourage foraging, the tightening of belts, and perseverance.

Martin, unfortunately, added worse news. Supplies, particularly food, that had been obtained could not be preserved without salt. Food, especially meats, went bad quickly and were wasted without salt. Martin apologized to Greene, explaining, “we are sorry there is not as much Salt in the possession of the Commissioners of Trade as we were taught to believe from them, they having bartered some for Tobacco to purchase more but in this article, we hope to have a large Supply soon.”[16] Expectations for salt turned into desperation. Greene waited a week, and then penned a letter to Robert Gillies to ask about salt. The food that had been acquired was at risk of spoiling. In desperation, he told Gillies, “we have large quantities of provision which must perish unless we immediately get a quantity of salt.”[17] Likely much of the food went bad. Patriot officers stationed on the coast in Wilmington, North Carolina tried to obtain it from Bermuda. They refused because they, “disposed of it to the commissioner for receiving the Specific tax.”[18] Other salt was soaked by a “leaky vessel” from Charleston, South Carolina.[19] Food became only feast or famine, as salt became increasingly hard to obtain.

As a Quaker, Greene paid particular attention to expectable generosity of the devout and religious groups throughout the Carolinas. The Moravian settlements north of Charlotte, Salem and Bethabara were small, but they contained generous people. They provided for the destitute men, of both Patriot and Loyalist sentiments. Greene tried his luck with the devout by appeals to the injured. He explained,

This army is in the greatest distress, for want of chirurgical [surgical] instruments. I beg you to employ all the people, with whom you have influence in your society, & who are complete workmen, to make three or four sets for this army. I wish them to be completed as soon as possible. . . . I trust your patriotism & love of humanity will induce you to comply with [my] wishes; as you may save the lives of many good men. . . . I also should be glad to be informed upon what terms you will exchange shoes & leather for raw hides.[20]

The hides, among others, which Greene acquired in December came in helpful for trade. Using unneeded goods to acquire the important supplies for the army was a thoughtful way to furnish the southern army. Greene’s quartermaster skills became acutely helpful, and his skill and experience came through in trade.

As the requests for supplies mounted and the actually incoming of stores remained low, Greene needed trustworthy help. On January 7, 1781, he wrote tp North Carolina Colonial Governor Abner Nash asking for a new appointment. He carefully articulated that,

I have written to the Board of war on this subject, & recommend the appointment of Col [William R ] Davie for a commissary General, with the same power of displacing Superintendents of districts, & County commissioners that the Board of War have, & also that he be authorized to impress and collect provisions at such places as he may be instructed. Unless this measure is adopted & the superintendents & commissioners made to discharge their duty with fidelity I foresee the Army will be cramped in all its operations, if not disbanded for want of the means of support.[21]

At times, Greene received unexpected support. The other Southern colonies and their officers and Patriots were as generous to the new commander as they could be. On the January 13, Greene informed Morgan, to no credit of his own, that “there are six Waggon loads of cloth on the way from Charles Town to the Congaree river the property of one Wade Hampton who it is said wishes it to fall into our hands.”[22] Despite the gleeful news, Greene knew the word wish all too well. Still, the generosity of the surrounding peoples was important exterior support for the southern commander.

As Christmas transitioned into late winter and early spring, Greene wrote General Washington a letter with an all-too-familiar tune: “our supplies of provisions are growing more precarious; and the other Stores which I can only look for from Philadelphia, do not arrive in such quantities, as to replace those which are daily destroyed in service.”[23] Greene had managed to secure some provisions, such as the wagons, but the army of the Southern campaign struggled needlessly. Eventually, a full month later on February 28, the supplies did come from Philadelphia. Greene’s letter continued and did not offer all good news: “Of the troops raised by the State of Virga last Summer, 400 are now at Chesterfield Court house naked and unable to march. But the Baron Steuben has detained some clothing coming from Phila. which will enable him to send them forward immediately.”[24] As Greene portrayed in his letters repeatedly, supplies never more than trickled into camp.

Throughout the months of December and January, Greene tried constantly to acquire supplies, often to no avail. With Morgan and Greene separated, the Patriot officers knew that the British would seek to take advantage of their destitute state and divided army. On January 18, 1781, two days after the Battle of Cowpens, South Carolina, Daniel Morgan and his army fled north to Beatties Ford on the Catawba River, meeting Greene there on January 30 with the British in hot pursuit. Despite Greene and Morgan’s lack supplies and men, the spring campaign began in earnest. Morgan has secured a significant victory at Cowpens, but the war remained to be won. The remarkable aspect of Nathanael Greene’s command is not that he secured bountiful of stores—food, clothing, and supplies—but that both he and Morgan were able to contend with a formidable British army despite the lack of supplies. That the Patriots remained in the field is an outstanding testament to Greene’s perseverance and leadership. The Patriot men who fought for their liberties did so despite their destitution. Supply troubles persisted for Greene throughout all of 1781. As he was pursued north in what became known as the Race to the Dan River, Greene’s men were wet, soaked, and desperate, and their condition would not change dramatically but their resolve hardened.

The command of the Southern Department is easily forgotten in the broader war for independence. Yet it involved no less sacrifice or valor than campaigns in the North. Without a competent army in the South, the war would have inevitably turned, likely in heavy favor of the British. General Cornwallis would have had liberty and freedom to move as he wished and support the war in the North as needed. Southern supplies, even if precarious, would have been sucked into the British war machine. Southern sentiment against British occupation likely would have more easily devolved into a desire for peace, even if under British authority.

The Southern army was not well supplied. European supplies struggled to reach the Patriot soldiers. Debt, lack of money, stolen goods, and empty promises remained constant friends of Greene in the Carolinas. But despite the absence of good supplies, he maintained a command that could contend in battle with the major British forces at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. The remarkable nature of remaining in the field despite the absence of supplies, represents the true, almost antithetical, heroism of the Southern army, and Greene was the man for the job of command. His quartermaster experience, with supply shortages, and his experience under Washington that the war could still be fought despite those shortages, afforded him consistent resolve. This resolve shows through most clearly in March in a letter Greene wrote to Washington. Three days after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Greene expounded:

The service here is extreme severe, and the Officers and Soldiers bear it with [a] degree of patience, that does them the highest honor. I have never taken off my clothes since I left the Pedee [January 18]. I was taken with a fainting last night, owing I imagine to excessive fatigue, and constant watching. I am better to day, but far from being well.[25]

Greene suffered as his men suffered, and he fought as his men fought. Shortages, destitution, and exhaustion were not just the way of the army, but the way of the commander. Yet, despite all that they lacked, Greene, Morgan, and the ordinary Patriot soldiers of the Southern campaign fought the good fight and finished their race to the liberty of the Southern colonies.

[1]Nathanael Greene to Thomas Jefferson, December 6, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives (original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 4, 1 October 1780 – 24 February 1781, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 183–185), founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0222.

[3]Greene to John Cox, in Richard K. Showman, Margaret Cobb, and Robert E. McCarthy, eds.,The Papers of Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press for Rhode Island Historical Society, 1976), 7: 81.

[4]Greene to George Washington, December 7, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04138.

[5]Greene to Horatio Gates, December 8, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0684.

[7]John Mathews, for Committee of Congress, to Greene, December 12, 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives, (original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 2, 20 March 1780 – 23 February 1781, ed. William T. Hutchinson and William M. E. Rachal (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962), 235–236), founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-02-02-0132.

[9]Mathews to Greene, November 27, 1780,”Founders Online, National Archives (original source: The Papers of James Madison, 2: 207n2), founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-02-02-0118.

[11]Greene to Robert Rowan, December 26, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr15-0133.

[12]Greene to Washington, December 28, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr15-0136.

[13]. Greene to Samuel Huntington, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 8.

[14]Greene to Daniel Morgan, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 22.

[15]Alexander Martin to Greene, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 44.

[17]Greene to Robert Gillies, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 83.

[18]John Bradley to Greene, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 104n.

[20]Greene to the “Head of the Moravian Society, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 61.

[21]Greene to Abner Nash, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7:63.

[22]Greene to Morgan, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 107.

[23]Greene toWashington, January 24, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04635.

[24]Greene to Washington, February 28, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-05041.

[25]Greene to Washington, The Papers of Nathanael Greene,” 7: 454.

11 Comments

Excellent read! Makes me wonder about how the lack of supplies in the southern campaigns influenced the army’s relationship with locals who weren’t eager to support the army.

Ms. Long: to answer your question, you may want to read Wayne Lee’s Crowds and Soldiers in Revolutionary NC (2002).

One of my favorite Greene quotes from this period is when he selected Colonel William R. Davie as his commissary. Davie replied that as a cavalry officer he knew nothing of money and accounts. “The General replied that as to money and accounts the Colonel would be troubled with neither, that there was not a single dollar in the military chest nor any prospect of obtaining any….” Davie had to subsist the army in the same way he subsisted his partisan corps of militia in the previous six month. “The General’s eloquence prevailed” and Davie accepted the position with the caveat that is be as short a term as possible.

Might the author support his claim that Greene was “scholarly and bookish”? Yes, he read widely, I agree. But with little formal education I doubt that he’d be considered bookish. It’s also well known that Greene left the Quakers well before the period he has the Southern Dept. command. On one minor point, in 1781, North Carolina had no Colonial Governor, since statehood came about several years prior to 1781.

Mr. Mass, first, let me say that I have only read the introduction to your recent work on Guilford, but enjoyed it greatly. I commend it so far! That being said, I can speak to this well-founded critique somewhat. I did leave out portions, being an essay, because not everything can be essential.

Greene’s willingness to read beyond his low education would be the reason for the term “bookish.” He was not Jefferson by any means, however he did present a certain desire to be self taught. He did read in military tactic and applied its minimal encounters well. He certainly had a good enough memory to make the best use of a minimal education. I do not mean the term in the broader perspective of well-educated. I can see a a pointed term would offer clarification, but I do think there is some justification in its use.

I also understand that the legislature had a provisional head, but it was not a governor. For general readership, I have used the familiar term.

I appreciate your helpful critiques. Thank you!

Mr Copeland:

Thank you for complementing my book, I hope you enjoy it. I think I would agree with you that he was bookish but I would not call him a scholar given his lack of formal education. What is this article part of? In other words is it part of a larger project that we can expect to see? If so I very much look forward to it.

Mr. Mass, I can agree to the dissent of “scholarly” as a term. I think this is a good encouragement moving forward to choose words with immense particularity, even more than I currently do.

I have wanted to do something larger on Greene for sometime. It is not currently part of a larger project, better scholars have written well on him, and because Greene has been well thoroughly considered. With your work, Babits/Howard work on Guilford, Terry Golway, and others, I have not found a particular focus for a larger project. On your recommendation, I will have to give it some more thought! Thanks again!

We can never fully appreciate what the Patriots have done for us. May I add to the discussion that Nathanael Greene personally took out a loan with John Banks to purchase supplies for the Southern troops. John Banks did not live up to his end of the bargain, leaving Greene responsible for repayment of the loan. Greene struggled to pay back the debt until his death.

I don’t think the definitive biography of Greene has been written. There’s a lot more room to explore especially since the published papers of his are so extensive. If you do decide to write more on him I would recommend contacting Charles Baxley of the southern campaigns of the American revolution website.

Do you happen to know if anyone has bothered to write an article or book about Colonel James Webster who served under Cornwallis during the Southern Campaigns 1780-1781? I am tracking that he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15 March 1781 and was buried near Elizabethtown, NC as the British Army was marching towards Wilmington, NC. I’ve always wondered if Colonel James Webster’s death had any impact at all on Cornwallis’ decision to go into Virginia vice returning to South Carolina. I realize Cornwallis and Clinton didn’t see eye to eye on many things.

Was Nathanael Greene “well educated”? He assembled an extensive library on Greek and Roman history, as well English history. Growing up he was tutored by Ezra Stiles who later became President of Yale University. He was also extremely inquisitive and always hungry to learn more. So was Nathanael Greene an “educated man.” The proof is in the pudding. No unknowledgeable person could have pulled off what he was able to do, and not just in the South. Washington appointed Greene military commander of Boston when the British sailed away. That appointment indicates the high level of responsibility Washington felt Greene had in the battle of Boston, although most of it occurred behind the scenes.