Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery in 1849. She became a major conductor on the Underground Railroad, as well as an advocate for Women’s Rights. A year later the Compromise of 1850 included a controversial Fugitive Slave Law that compelled all citizens to help in the recovery of fugitive slaves. Free Blacks formed more Vigilance Committees throughout the North to watch for slave hunters and alert the Black community. In 1851, federal marshals and Maryland slave hunters sought out suspected fugitive slaves in Christiana (Lancaster County), Pennsylvania. In the ensuing struggle with Black and white abolitionists, one of the attackers was killed, another was seriously wounded, and the fugitives all successfully escaped. Thirty-six Black men and five white men were charged with treason and conspiracy under the federal 1850 Fugitive Slave Law and brought to trial in federal court at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. This trial became a cause célèbre for American abolitionists. Attorney Thaddeus Stevens defended the accused by pleading self-defense. All the defendants were found innocent in a jury trial. That same year the first book about African Americans’ contributions during the Revolutionary era was published in Boston, William Nell’s The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.

In 1852 Congress repealed the Missouri Compromise, opening western territories to slavery and setting the stage for a bloody struggle between pro and anti-slavery forces in Kansas Territory. Five years later, in March 1857, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision against Dred Scott, and enslaved man whose owners took him to a state where slavery was illegal. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court ruled that Black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.”

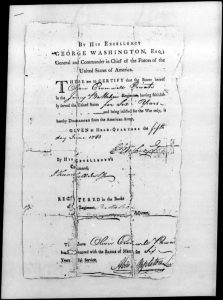

Amid all of these events, Revolutionary War veteran Oliver Cromwell celebrated his one hundredth birthday in 1852. At twenty-five years of age, he had enlisted for the duration of the war in May 1777 and served to June 1783. His discharge certificate, on file with his pension papers, states, “Oliver Cromwell Private has been honored with the Badge of Merit for Six Years Faithful Service.” Shortly after his enlistment, by his own account, he “was in the Battle of the Short Hills where Captn [James] Laurie was wounded and taken prisoner.” In an 1852 newspaper article Mr. Cromwell claimed to have been in the actions at “Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Monmouth and Yorktown, at the latter place, he told us, he saw the last man killed . . . he was also at the battle of Springfield, and says that he saw the house burning in which Mrs. [Hannah] Caldwell was shot, at Connecticut Farms [June 7, 1780].” The first two cited events occurred before his 1777 enlistment, so those claims are suspect, but Cromwell was almost certainly present at the other battles.[1] The old soldier also recalled quite accurately the army’s 1782–83 organizational change:

he enlisted [in 1777] . . . in the second Jersey Regiment commanded by Colonel Shreve . . . [after Captain Laurie’s death in captivity] the deponent was put under the Command of Captain [Nathaniel] Bowman—that not long before the discharge of the Deponent from service—the regiment to which he belonged was reduced to a Battalion—when he thinks he was commanded by Captain Dayton[2]

Cromwell did indeed serve in Bowman’s light infantry company from July 1777 to December 1782. In January 1783 he was transferred to the Captain Absolum Martin’s (4th) company, Colonel Cumming’s New Jersey Battalion.[3]

The man who is arguably the best-known Black New Jersey Continental may have had Native American heritage as well. In 1852 he was called “an old colored man” and then “half-white”; Eric Grundset’s work, Forgotten Patriots, notes that in some records he was termed a “Mulatto,” in others Indian. It would not have been at all unusual for Cromwell to have Indian heritage, as intermarriage between the region’s Lenni Lenape tribe and English settlers or Africans did occur from the late seventeenth century into the eighteenth century. The question will likely never be settled but does bring to mind a related matter. What were the terms used to denote persons of color of mixed race? Mulatto seems to have been reserved for people with Black and white parentage; some people so-termed were described as having “black hair, [and] yellow skin,” but yellow was not then used as a synonym for mulatto. Mustee, and less often “mustezoes” or “Mestizoes,” was used to denote African and Native American forebears, at least in Rhode Island and the Carolinas.[4]

Oliver Cromwell was interviewed in May 1852 by a reporter from the Burlington Gazette, Burlington, New Jersey, who wrote this story:

I am 100 Years Old To-Day!

His name is Oliver Cromwell, and he says he was born at the Black Horse, (now Columbus,) in this county, in the family of John Hutchin. He enlisted in a company commanded by Captain Lowery, attached to a second New Jersey regiment, under the command of Col. Israel Shreve. He was at the battles of Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Monmouth, and Yorktown, at which latter place, he told us, he saw the last man killed. Although his faculties are failing, ye he relates many interesting reminiscences of the Revolution.

He was with the army at the neglect [sic] of the Delaware on the memorable crossing of the 25th December 1776, and relates the stories of he battles on the succeeding days with enthusiasm. He gives the details of the march from Trenton to Princeton, and told us, with much humor, that they “knocked the British about lively” at the latter place. He was also at the battle of Springfield, and says that he saw the house burning in which Mrs. Caldwell was shot, at Connecticut Farms.

His memory in reference to persons engaged in the war is very good, and frequent application have been made to him by persons seeking evidence for pensioners.

He says that the branch of the army with which he was connected was disbanded at Little Britain [now part of the town of New Windsor], in New York, a short distance from West Point. His discharge was signed by Washington, and stated that he was entitled, “by reason of his honorable services, to wear the badges of honor,” which he did for many years after peace was declared. His eye brightens at the name of Washington, and in all his conversations he exhibits that deep-seated attachment to his illustrious commander for which all soldiers of the Revolution are celebrated.

His discharge was taken from him, at the time he made application for his pension, by the Pension Agent, Joseph McIlvaine, esq., and by him forwarded to the War Department, where it doubtless remains now. He mourns over it very much, and always speaks of its being taken from him with tears in his eyes.[5]

[1]National Archives (United States), Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804), Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, Washington, D.C., reel 695, Oliver Cromwell (S34613), including copy of clipping from the Burlington Gazette, New Jersey, 1852.

[2]Oliver Cromwell (S34613), National Archives Pension Files.

[3]Revolutionary War Rolls (National Archives Microfilm Publication M246), Record

Group 93 (Washington, D.C., 1980), reels 55-63, muster and pay rolls of the four New Jersey regiments, plus the 1783 regiment and battalion. National Archives, Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War (National Archives Microfilm Publication M881), Record Group 93 (New Jersey), Second New Jersey Regiment, Oliver Cromwell, p. 1-74; Cummings’ Battalion, p. 1-2.

[4]Oliver Cromwell (S34613), including copy of clipping from the Burlington Gazette, New Jersey, 1852, National Archives Pension Files. Eric Grundset, Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (Washington, D.C.: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008), 383. Jean R. Soderlund, Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), 181. Joseph Lee Boyle, “He loves a good deal of rum . . .”: Military Desertions during the American Revolution, 1775–1783, Vol.2 (30 June 1777–1783) (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2009), mustee, 257; yellow, 294–295, 298–299. Patrick Neal Minges, ‘all my Slaves, whether Negroes, Indians, Mustees, Or Molattoes’: Towards a Thick Description of ‘Slave Religion’ (1999), are.as.wvu.edu/minges.htm. Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth Century Chesapeake & Lowcountry (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 240, 330, 479, 482. Warren Eugene Milteer, Jr., “The Complications of Liberty: Free People of Color in North Carolina from the Colonial Period through Reconstruction,” (PhD dissertation: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), 82n, 84, 86, 88.

[5]Burlington Gazette (New Jersey), late May 1852. The issue in which this widely-reprinted story appeared has not been determined; the story ran in the nearby Trenton State Gazetteon May 31.

Recent Articles

The American Princeps Civitatis: Precedent and Protocol in the Washingtonian Republic

Thomas Nelson of Yorktown, Virginia

The Course of Human Events

Recent Comments

"General Israel Putnam: Reputation..."

Gene, see John Bell’s exhaustive Analysis, “Who Said ‘Don’t Fire Till You...

"The Deadliest Seconds of..."

Ed, yes Matlack's son was reportedly a midshipman on the Randolph. That...

"The Whale-boat Men of..."

From my research the British Navy kept a very regular schedule across...