On the morning of October 9, 1779, one of the bloodiest and most forgotten battles of the American Revolution took place during the Siege of Savannah, Georgia. Two columns of American and three of French troops stormed British entrenchments that defended the town. The attacking allies suffered bayonet charges and a rain of bullets and cannon shot from their well-fortified foes. The attackers did not shoot back, having been told to hold their fire until they reached the enemy redoubts. Of the American Continentals, militia from Georgia and South Carolina, Haitian and Irish soldiers, and French Regulars, 244 men were killed, almost 600 were wounded, and 120 men were taken prisoner, from a total of 5,000 soldiers.

Defenders of the British lines were Americans in the service of the King (Loyalists and Tories) from Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina supported by Scottish Highlanders, British infantry and artillery, Loyalists from New York and New Jersey, Hessians, armed slaves, and Indians. Overall, the King’s forces lost an estimated 40 killed, 63 wounded, and 52 missing from a combined force of 3,200 men.[1]

The French officer in charge, Vice Admiral and Lieutenant General Comte d’Estaing, had taken personal command of the French columns from the front, and at the last moment, he led the charge towards the British entrenchments as his men yelled “Vive Le Roi!” D’Estaing thus unintentionally fouled the attack plan and caused the columns to collide before they could reach their objectives.

D’Estaing reached the enemy ramparts but was shot in the arm and, while rallying his men three times, took another wound in the calf. A drummer boy held him up. He fell and was left among the dead. Captain Laurent-Jean-François, Comte de Truguet, who had reached the British ramparts, rescued his commander after two grenadiers died in the same effort.[2] The “585 volunteer colored chassars” of the Haitian battalions that the French had kept as a reserve covered the retreat and saved the American and French forces.[3]

That evening, the Comte ordered an end to the siege. John Wereat, head of Georgia’s ad hoc rump state government, visited d’Estaing and promised the admiral citizenship and 20,000 acres in Georgia for coming to the aid of the state. D’Estaing called the offer a balm for his wounds and wrote to Thomas Jefferson that he valued nothing more than this granting of citizenship in the new nation.[4]

Jean-Baptiste-Charles-Henri-Théodat-Hector, the Comte d’Estaing du Saillans, came from a family prominent in French affairs for over five centuries and was raised with Louis, the Dauphin (son of King Louis XV and father of Louis XVI). D’Estaing had a long career in the service of France in the Americas and India as admiral, general, and governor. He knew Benjamin Franklin from before the American Revolution and worked with him in Paris.[5]

Remembered as brave, hardworking and intelligent, d’Estaing consistently was unlucky or proved incompetent, as he demonstrated in his failed efforts to help George Washington and the American cause in 1778. Sir Henry Clinton, British commander for North America, however, wrote that d’Estaing’s fleet had been a disaster for the British as it exposed weaknesses in the Royal Navy. D’Estaing’s expedition captured or caused the destruction of several British ships and resulted in the capture of Grenada and St. Vincent while forcing Britain to defend Jamaica. His campaign almost delayed the second British invasion of the South for a year, and potentially forever.[6]

D’Estaing returned to Paris a hero, receiving a parade and being personally welcomed at Versailles by the King. He successfully pushed for sending the army and fleet to America under Rochambeau that, with George Washington’s army, forced the British surrender at Yorktown. D’Estaing assembling a huge fleet to return to the Caribbean encouraged the British to agree to the Treaty of Paris that ended the war in 1783.[7]

The Admiral reminded the state of Georgia of the promises of the land shortly after the war ended. Governor John Houstoun signed four grants of 5,000 acres each in Franklin County for d’Estaing on September 28, 1784.[8] Today, the land is in Clarke, Jackson, and Madison counties.

In 1790, plans were made to settle French families on d’Estaing’s lands but nothing came of that project. On July 31, 1793, the Comte sold 16,000 of the 20,000 acres in the grants to Francis Lewis Taney (1762-1802), for £110,000.[9] Taney, a Maryland-born tobacco merchant trading in Hamburg and elsewhere while serving as America’s customs agent in Harve, France. Taney married Marie á Arsene Bérénice Gauvain, a daughter of respected Havre merchant Michel William Gauvain.[10]

The Reign of Terror, the period of official executions during the French Revolution of 16,596 people from June 1793 to July 1794, took d’Estaing’s life. He had joined the new French Republic but he would not disavow his friendship with Queen Marie Antoinette. Consequently, he was died on the guillotine on April 28, 1794. As d’Estaing was officially an enemy of the state, the French government could claim his remaining property, including the 4,000 acres he still possessed in Georgia.

With d’Estaing’s maternal grandmother Charlotte Françoise Jacqueline de Manneville, Marchioness de Maulévrier, going to her death on the guillotine on July 26, 1794, her grandson (d’Estaing’s first cousin), Ḗdouard-Charles-Victurnien de Colbert-Maulévrier (1758-1820) declared himself as d’Estaing’s heir. He had served under the Admiral in 1778 and 1779 and later under de Grasse at Yorktown as a sea captain; he emigrated to Philadelphia in 1796. In 1799, he hired Alexander Hamilton as his attorney to claim the d’Estaing lands and he appointed Lewis Sewall of Columbia County, Georgia, (ironically, Francis Taney’s former brother-in-law) as his local agent. Colbert denied the rights of anyone else to the lands.[11]

In 1799, the Georgia legislature passed an act making French refugee John d’Antignac/Dentignae administrator of the d’Estaing estate, likely for Colbert. D’Antignac had left Martinique to join the American cause, serving as a captain at Saratoga in 1777 under Gen. Horatio Gates and later under Washington at Yorktown. He became a prominent businessman and official in Augusta, Georgia, where he helped immigrants from France in obtaining United States citizenship.[12]

Colbert sold all 20,000 acres of the d’Estaing grants to Revolutionary War financier Robert Morris and his partner John Nicholson. Eventually, they formed the North American Land Company that claimed millions of acres, some real and others non-existent, in several states. Colbert had loaned money to Morris, a debt backed by Morris’s land speculations in Genesee County, New York.[13]

As early as 1795, Morris had tried to secretly obtain the d’Estaing lands from Colbert for £4,000 to £5,000 through United States Ambassador to Britain Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. He had the opinion of Georgia’s United States Senator James Jackson of the land being worth £40,000. Morris and Nicholson had planned to sell their lands to French families seeking to immigrate to the American frontier to escape the political turmoil in Europe. Towards that end, Morris associates in France instituted the infamous XYZ scandal to improve the tense relations between France and the United States in order to protect the Morris land scheme in Georgia and elsewhere. No European settlers moved to American as part of these projects.[14]

When Robert Morris finally went bankrupt (his “bubble” of debt and land, real and imaginary, collapsed), the d’Estaing lands were not seized by Morris’s creditors because they never belonged to Colbert. In 1765, legally separated from his wife Marie-Sophie Rousselot (d. 1792) since 1756 because his gambling debts posed a threat to her property, and with their son and his only legitimate child Théodat dead in 1759, the Comte d’Estaing legitimized his half-sister Lucie Madeleine d’Estaing, wife of Count Francois de Boysseuth but the former mistress of King Louis XV, in 1768. She was his real heir. The French government restored the property seized during the Terror in 1796.[15]

In 1798, Madame de Boysseuth sold the rights to the remaining 4,000 unidentified acres of the d’Estaing grants to Bérénice Taney, Francis’s wife, by then living in Baltimore. Those undesignated 4,000 acres were safe from Francis Lewis Taney’s creditors, as under French law Bérénice could own the land as non-community (separate) from her husband. The Taneys briefly moved back to France by 1801, where he served as America’s commercial agent in Ostend. He died in 1802 in Maryland.[16]

Francis Lewis Taney’s financial affairs by then had become embarrassed during the trans-Atlantic chaos of changes in debt practice, law, and trade brought on by the French Revolution, the drop in land prices brought on by the economic Panic of 1797, and the United States’ Quasi-war with France (1797-1800). His financial problems even came before the United States Supreme Court.[17]

Francis Lewis Taney’s creditors took the 16,000 acres he bought from d’Estaing and they appointed prominent surveyor Levin Copeland Wailes as their representative to divide the lands into smaller parcels for sale at the house of Francis Nunn on the mouth of Parke’s Creek in Clarke County, Georgia on January 17, 1803. Bérénice Taney authorized Lewis Sewall to sell her 4,000 acres at the same auction.[18]

The d’Estaing lands were thus seemingly brought together for the last time for this sale in 1803. They were not sold, however. Rosalie Gauvain claimed that she and her husband Michel-Angel Gauvain, former secretary to James Monroe in France, had traded her de Trobriand family’s lands in Martinique to her brother-in-law Francis Lewis Taney for the 20,000 acre d’Estaing grants, therefore making the land the property of Bérénice’s brother Michael-Angel Gouvain. He had married Rosalie Renee Marie Claudine Josephine Yvonne Vincent Denis de Keredern de Trobriand, widow of Gen. Thomas Adrien De Le Perriére,in 1799 and, in 1805, Michal moved to the then frontier settlement of Athens, Georgia. In 1809, he sold some of the d’Estaing land but only as an agent for his sister Bérénice Taney. She paid the taxes on the 20,000 acres in 1810.

Michel-Ange’s wife and the children reunited with him in Athens in 1810 but he and Rosalie separated before 1815 and divorced in 1821. He gave all of his property to his wife for support of their children, including the d’Estaing lands, in a deed of March 24, 1812. On April 10 and 13, 1812, however, Bérénice Gauvain Taney sold the 20,000 acres of d’Estaing grants to Michel-Ange Gauvain for $5,000. Likely, the Taneys had not formally sold the property to Gauvain until 1812.[19] He sold off parts of the d’Estaing grants, lost parts in sheriff’s sales for debt, and bought back parts over a period of time. In 1814-1815 alone, he lost 5,000 acres of the d’Estaing lands in sheriff’s sales for debts. Michel-Ange Gauvain died in New York City in 1853.[20]

Whomever officially owned the d’Estaing grants, other people occupied that ground. Settlers did not know of or ignored the d’Estaing entitlement and built roads, took out land grants, and sold the lands without permission. In 1804 and 1807, Bérénice Taney sued in federal court to have persons evicted from the d’Estaing grants.[21] These families also lived illegally on nearby Indian lands by claiming to be being renters and spouses of the Indians. Other settlement schemes in the area included the Wofford settlement, the Tallassee colony, and the illegal occupants of land on the Appalachee River. A visitor was falsely told, likely by the evicted, that the Comte d’Estaing had not died in the French Revolution but had brought hundreds of family members and friends from France to settle on his grants. The writer also falsely claimed that d’Estaing led the Murrell Gang, a band of horse thieves who, except for John Anderson Murrell himself, only existed in myth.[22]

Gauvain was not the last person to own all of the d’Estaing lands. With war with Great Britain a real possibility in 1798, the United States government had imposed a direct tax on its citizens. Regardless of who owned the land, the federal taxes on the d’Estaing lands had gone unpaid. The federal government condemned and foreclosed on the land and many other properties in the area in 1813.[23]

Wealthy Georgia planter Stevens Thomas bought the whole 20,000 acres, including the improvements left from the people ejected from the land, for only $38.70 at a federal auction on September 8, 1813. He thus became the last person to own all of the d’Estaing lands. Almost immediately, Thomas and his partners William Billups and John Brown began selling off the lands. The Gauvains’ daughter Roselia Maria Antoinette Claudine Josephine Gauvain bought 1,234 acres for $5 from the 5,000 acre tract on Nocatchee Creek in Madison County and Rosalie Gauvain’s son Ange A. DelaPerriere bought 2,500 acres, what remained of two tracts of 5,000 acres each in Jackson County, for $5.00.[24]

The Gauvain family reacquired much of the d’Estaing lands, holding onto it for many years. On August 1, 1819, their only daughter Maria married Dr. Robert Raymond Harden (1793-1843). In 1820, the Hardens together owned 4,500 acres and Rosalie’s son from her first marriage owned 2,500 more. Ten years later, Rosalie Gauvain owned 3,000 acres and the Hardens 1,786 of the original d’Estaing grants.[25] Rosalie de Trobriand Gauvain became a socialite in frontier Athens, Georgia. She left a memoir of having been a close friend of the Empress Josephine and of dancing with Napoleon. The Gauvins have descendants living today in Northeast Georgia.[26]

The 20,000 acres of meadows, streams, and woods that the Comte d’Estaing received but never saw had a local history of bondage, dreams, homes, settlements, slavery, etc. unlike the millions of square miles of like ground that represented of much of the history of America and France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Both histories go unnoticed to the travelers who pass on the highways through these lands that even today do not have town names to proudly commemorate this special past.

[1]Gordon B. Smith, Morningstars of Liberty: The Revolutionary War in Georgia, 1775-1783, 2 vols. (Milledgeville, GA: Boyd Publishing, 2011 and 2014), 1: 166-77; Alexander A. Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah: The Story of Count d’Estaing and the Siege of the Town in 1779 (1968, revised edition, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1951), 91-103; Dan Morrill, Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution (Baltimore: Nautical & Aviation, 2011), 64. The author acknowledges the research previously done on this topic by Daniel N. Crumpton, Susan Frances Barrow Tate, and Merita Rozier.

[2]Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 94, 96, 99, 100, 170n5. Trugent would later become an Admiral of France. Asa Bird Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France(Providence, RI: Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati, 1905), 187.

[3]Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 25-27, 50, 101, 139; Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France, 32. A monument in Savannah stands in honor of the Haitian troops.

[4]Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 117, 170n10.

[5]For the life and background of the Comte d’Estaing see Jean Joseph Robert Calmon-Maison, L’Amiral d’Estaing (1729-1794)(Paris, France: Calmann-Lévy, 1910).

[6]James Breck Perkins, France in the American Revolution (Boston: Houghton Miffin, 1911), 258-73; Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France, 110-12; Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 13-14, 178; William C. Stinchcombe, The American Revolution and the French Alliance (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969), 48-52, 54, 56, 58, 60; Edward Martin Stone, Our French Allies (Providence, RI: Providence Press Company, 1884), 126-28; Thomas Shachtman, How the French Saved America (Baltimore: St. Martin’s Press, 2017), 308; Robert S. Davis, “Charles-Henri-Theodat, the Comte d’Estaing,” in Richard Blanco, comp., The American Revolution: An Encyclopedia, 2 vols. (New York: Garland, 1993), 1: 514-15.

[7]Stone, Our French Allies,127-28; diary of Simeon Prosper Hardy, 226, 228, Department des Manuscripts, Manuscrits Français Bibliothéque Nationale, French Transcripts, 6680-6687, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington; Mark Mayo Boatner III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York: David McKay Company, 1988), 349-50.

[8]Warrant for survey, Comte d’Estaing, Loose Headright and Bounty Grant Papers, State Plat Book A (1779-1785), 110-11, and Comte d’Estaing to ?, n. d., File II Names, Record group 4-2-46, and [French consulate] to Governor of Georgia, July 14, 1785, in Louise F. Hays, “Georgia East Florida-West Florida and Yazoo Land Sales 1764-1850,” (typescript, 1941), n. p., Georgia Archives, Morrow; Comte d’Estaing to Cavalier De la Luzerne, n. d., Joseph Valence Bevan Papers, Mss 71, Box 1, folder 10, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah.

[9]“Plan d’un établissement a faire dans la Gáorgie, l’un des Ḗtats—Unis del’Améique, dans’les terres de M. le Cte. d’Estaing,” KF 1790, Rare Books and Manuscripts, New York Public Library; Daniel Nathan Crumpton, Wilkes County, Georgia Land Records Volume One (Warrenton, GA: The author, 2014), 408; Faye Stone Poss, comp., Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts Books A-D 1796-1808 (Fernandina, FL: Wolfe Publishing, 1998), 203.

[10]Edouard Delobette, “Ces ‘Messieurs du Havre”: Negociants, Commissionnaires et Armateurs de 1680 á 1830,” (Ph.D. diss, University of Caen, 2002), 285 n. 666, 800, 1066, 1540, 1639, 1835; William Vans, A Short History of the Life of William Vans, Native Citizen of Massachusetts(Salem, MA: William Vans, 1825), 11; marriage license of Michel Gauvain, March 11, 1823, Marriage Licenses 1809-1950, Probate Court, Mobile County, Alabama; Parish Register, volume 5 (1830-1839), 555, Baton Rouge Diocese, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Bérénice and Michel-Ange Gauvain were also the siblings of Rosalie Gauvain, the wife of William Vans and consequently the center of one of the longest litigations in the early history of the United States. See John, Charles R., and Francis Codman, An Exposition of the Pretended Claims of William Vans (Boston: S. N. Dickinson, 1837).

[11]Chevalier de Colbert to Alexander Hamilton, March 9, 1799, Alexander Hamilton Papers, 1708-1917, Mss 24612, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington; Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 11, 130; “To James Armstrong,” Augusta(Georgia)Chronicle, July 14, 1798, p. 3 c. 4. Colbert returned to France in 1803, during the Restoration, and became a rear admiral and a member of the Society of the Cincinnati. He died in Paris in 1820. Gardiner, Order of the Cincinnati in France, 37, 129-30.

[12]Legal notice and “Augusta City Hotel,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State (Georgia), November 3, 1798, p. 1 c. 2, and September 4, 1802, p. 1 c. 4; Raymond J. Adamson, “I Pledge allegiance,” Ancestoring III (Augusta: Augusta Genealogical Society, 1981), 9. John Dentignac/d’Antignac’s full name was Louis Charles Jean Baptiste Chambarow, Chevalier d’Antignac. D’Antignac Street in Augusta, Georgia is named for him. Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 2: 289; Revolutionary War Pension Claim of John d’Antignac, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Applications (National Archives microfilm M804, roll 739); “Obituary,” Georgian(Savannah), April 21, 1827, p. 2 c. 4.

[13]Daniel M. Friedenberg, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Land (Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1992), 174, 185, 346-47; and Aaron Morton Sakolski, The Great American Land Bubble: The Amazing Story of Land-Grabbing, Speculations, and Booms from Colonial Days to the Present Time (New York: Harper, 1932), 143.

[14]Ellis Paxton Oberholtzer, Robert Morris: Patriot Financier (New York: MacMillan, 1903), 307-308; Colbert to Hamilton, January 4, 1802, Alexander Hamilton Papers.

[15]Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 13, 127; Poss, Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts Books A-D, 151-53. For Lucie-Madeleine d’Estaing see Sylvia Jurewitz-Freischmidt, Galantes Versailles (Berlin: Karl Casmir Verlag, 2000).

[16]Barbara B. Oberg, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 44 vols. to date (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), vol. 34: 614n. Poss, Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts Books A-D, 172; Deed book GG (1889-1890), 111-16, Clarke County Superior Court, Athens, GA.

[17]Delobette, “Ces ‘Messieurs du Havre’,”: 183 n 5375, 285; legal notices, Maryland Gazette (Annapolis), November 13, 1788, p. 4 c. 1; court proceedings, National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser (District of Columbia), June 19, 1809, p. 4 c. 4; petition of Benjamin Stoddert and John Mason, House Committee on Claims for the 10th Congress (HR10A-F2.1), Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD; Fenwick v Sevis, 5 US 259 (1803).

[18]Legal notice, Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State (Georgia), November 27, 1802, p. 2 c. 2.

[19]Faye Stone Poss, comp., Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts, Books E-G 1808-1822 (Fernandina, FL: Wolfe Publishing, 2000), 128.

[20]Legal notices, Athens Gazette (Georgia), May 12, 1814, p. 4 c. 3, July 6, 1815, p. 4 c. 1, September 7, 1815, p. 4 c. 4; Poss, Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts Books A-D, 258, 278, 285; Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts, Books E-G, 1, 2, 17, 28, 71, 76, 84-85, 98-99, 107, 110, 126, 128, 133, 155, 352; and Clarke County (Athens), Georgia Newspaper Abstracts, 1808-1820 (Snellville, GA: The Author, 1998), 4, 27, 86, 112, 115, 130, 134, 141, 153, 189, 221, 222, 237, 243, 268, 279.

[21]D’Estaing plats, Archives Center—Jackson County, Jefferson, Georgia; Denn (Bérénice Taney) vs. Robert Fenn (Robert Freeman) 1804, Box 33 A-27, and Richard Smith (for Michael Taney) vs. Richard stiles, Thompson McGuire, and Sherwood Thompson, 1807, Box 46, file B-4, Savannah Circuit Court, National Archives at Atlanta, Morrow; Poss, Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts, Books E-G 1808-1822, 131.

[22]Mary B. Warren and Eve B. Weeks, comps., Whites Among the Cherokees Georgia 1828-1838 (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 1987), 227-31; “The Land Grant to Count D’Estaing,” Valdosta Times (Georgia), February 26, 1887, p. 1 c. 2-3; James L. Pinck, Jr., The Great Western Land Pirate: John A. Murrell in Legend and History (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri, 1981), 5-6.

[23]“Direct Tax,” Augusta Chronicle (Georgia), January 15, 1813, p. 1, c. 2.

[24]Marie Antonnette Gauaine file, Clarke County Estate Papers, Record Group 129-2-6, Georgia Archives, Morrow; Poss, Jackson County, Georgia Deed Abstracts Books A-D, 219, 222, 228, 229, 253, 322, 354; Mary Holt Abbe, comp., Clarke County, Georgia, Tax Digests, 1811-1820 (Athens: Clarke-Oconee Genealogical Society, 2004), 368.

[25]Abbe, Clarke County, Georgia, Tax Digests, 1811-1820, 15, 53, 97, 259, 261, 339, 369, 378, 379 and Clarke County, Georgia, Tax Digests, 1821-1830 (Athens: Clarke-Oconee Genealogical Society, 2006), 6, 60, 64, 115, 134, 184, 229, 283, 323, 334, 374, 387, 432, 476, 524.

[26]See Caroline Reese Collection, microfilm drawer 148, reels 43 and 44, the Marion Reese family Bible, microfilm drawer 149, box 32, Hardin/Pruitt Family Papers, 1814-1899, Ac 1980-0063M, and Georgia Society D. A. R., “Miscellaneous Genealogical Records, 1972,” 361-62, Georgia Archives, Morrow; Augustus Longstreet Hull, Annals of Athens, Georgia 1801-1901 (Athens, GA: Banner Job Office, 1906), 154-59, 452-53; Joseph Maddox, comp., Miscellaneous Records, Jackson County (n. p., n. d.), 14, 41; Gauvain File, Frances West Reid Genealogical Collection, Mss2451, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries, Athens.

4 Comments

Mr. Davis, Thank you for your fascinating article on d’Estaing!

This is a subject I’ve long wondered about, but having moved away from Georgia, is now difficult to research.

Does a map or description exist describing the boundaries of his lands, or better yet the lands of Madame Gauvin?

Do you know if she made any improvements to the land, for instance had a plantation there?

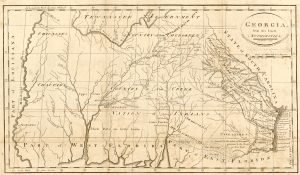

The locations of the d’Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton’s book Franklin County Georgia Land Records : boundaries as of 1784 (and later plats)

Fascinating! I also found interesting, that the Elberton, Georgia, on the map in the article is NOT the location of the current Elberton, Georgia! The one on the map is significantly south, while the one today was founded (1791) one year after this map’s publishing (1790) and is slightly north of Petersburg (now underwater, on the tip of Elbert County) on the map. Thanks for your research into a forgotten and interesting period! Source: born and raised in Elbert County

The new biography of Samuel Elbert by Ouzts describes the first Elberton