John Corlis (sometimes spelled Corlies) was a Quaker land owner who resided in Shrewsbury Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. He along with his mother owned six slaves. It has been reported that Corlis was a “harsh master” and whipped his slaves for trivial reasons. In the 1760s, Quakers in New Jersey had begun to emancipate their slaves when they turned twenty-one, but even after elders of the Shrewsbury Meeting met with Corlis, he still refused.[1] One of his slaves, twenty-one-year-old Titus (also referred to as Cornelius Titus) decided to take his fate into his own hands and ran away. As a result, the following advertisement appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette:

Three Pounds Reward

Run away from the subscriber, living in Shrewsbury, in the county of Monmouth, New Jersey, a Negroe man, named Titus, but may probably change his name; he is about 21 years of age, not very black, near 6 feet high; had on a grey homespun coat, brown breeches, blue and white stockings, and took with him a wallet, drawn up at one end with a string, in which was a quantity of clothes. Whoever takes said Negroe, and secures him in any gaol, or brings him to me, shall be entitled to the above reward of Three Pounds, proc. And all reasonable charges paid by John Corlis.

Nov. 8, 1775.[2]

Does the above-mentioned runaway slave, Titus, later become the leader of Loyalist Refugee raiders known as Colonel Tye?[3] Aside from a few reports in newspapers of the day, there is very little in the way of primary sources regarding Colonel Tye’s origin and activities. Most of what we know about Colonel Tye is grounded in tradition, legends, and folklore. As historian Michael Adelberg noted in The American Revolution in Monmouth County:

Though there is some dispute about Tye’s early life, recent scholarship concludes that Tye was the slave Titus, who ran away from John Corlies of Shrewsbury in November 1775. Tye was probably active in the early irregular military activities around Sandy Hook, though this cannot be proven.[4]

Coincidently, the Royal Governor of Virginia, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, gave his proclamation on November 7, 1775 that if a slave abandoned his Patriot owner and joined the British he would earn his freedom. Some of these runaway slaves were formed into a military unit known as the Ethiopian Regiment.[5] They fought in two engagements in Virginia but were eventually evacuated to New York in August 1776. In a number of stories and articles about Colonel Tye it is reported that when he fled Corlis he learned of Dunmore’s proclamation, made his way to Virginia and joined the Ethiopian Regiment, but there is no documentation for this action.[6] One historian, Graham R. Hodges, even places Tye at the Battle of Monmouth where he supposedly captured an American officer and took him to New York.[7]

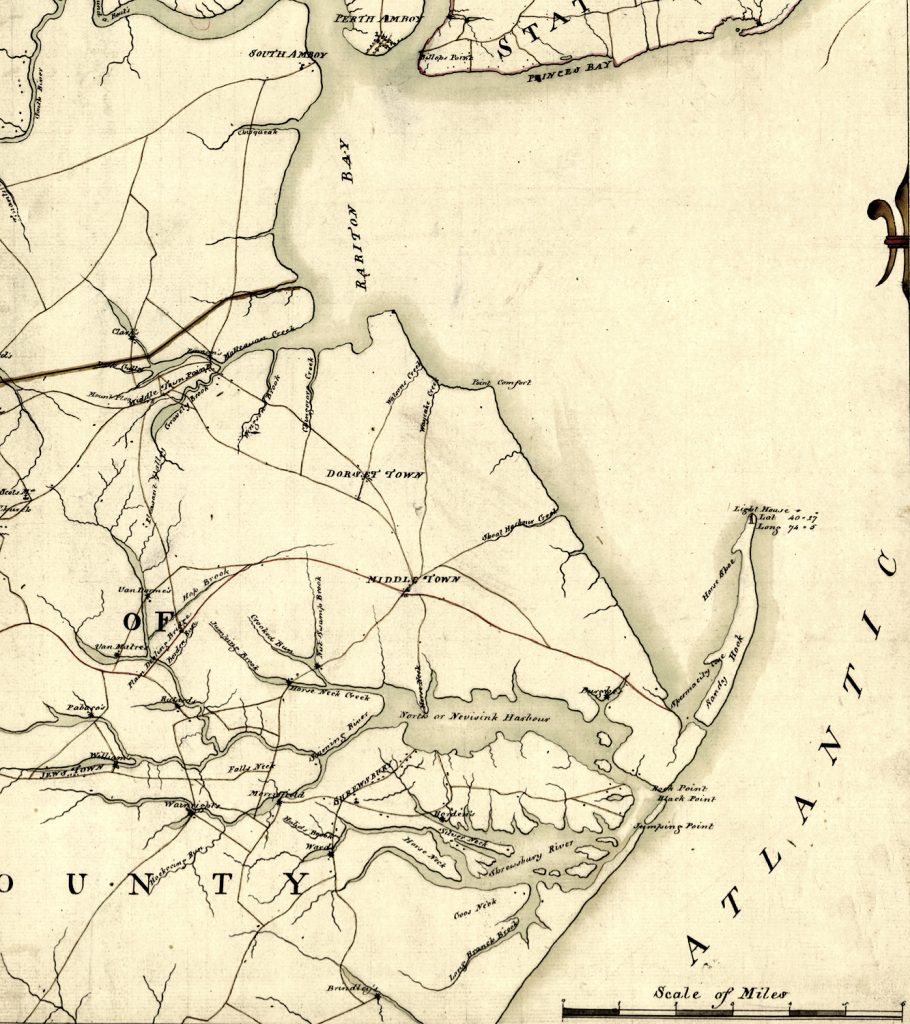

From 1776 to 1783, there were two permanent bastions of the British in New Jersey: Sandy Hook and Paulus Hook.[8] It was at Sandy Hook that runaway slaves and white Loyalists refugees set up an encampment that became known as Refugeetown. This served as the base of operations for Colonel Tye and it was from here that he led a mixed-race band that became known as the Black Brigade.[9] According to Hodges:

Tye’s familiarity with Monmouth swamps, rivers and inlets allowed him to move undetected until it was too late. After a raid, Tye and his interracial band would disappear again into nearby swamps, later returning to Refugeetown at Sandy Hook headquarters for maroon activities.[10]

The following incident, not explicitly mentioning Tye, was reported in the Royal Gazette on June 17, 1779: “On Tuesday 6th an inhabitant of said county [Monmouth] was taken off to the enemy by four negroes.”[11] Then on July 16 a raid occurred in Shrewsbury that frightened the Whigs of Monmouth County:

On Friday night, last about fifty negroes and refugees landed at Shrewsbury, and plundered the inhabitants of near eighty head of horned cattle, about 20 horses, and a quantity of wearing apparel and household furniture. They also took off William Brindley and Elihu Cook of the inhabitants.[12]

Attributing it to Colonel Tye, Adelberg noted: “This raid establishes Tye as Sandy Hook’s most capable irregular leader.”[13]

Beginning in Spring 1780, Colonel Tye led a series of raids that embellished his notoriety; Hodges described them in this way:

In a typical raid, Tye and his men aided by white refugees known as “cow-boys” would surprise Patriots in their homes, kidnap, carry off silver, clothing and cattle. For these accomplishments Tye and his men were paid handsomely, sometimes receiving five gold guineas.[14]

An example of this activity is a raid reported in the Pennsylvania Gazette on April 12, 1780:

On the 30th ult. a party of Negroes and Refugees, from the Hook, landed at Shrewsbury in order to plunder. During their excursion, a Mr. Russel, who attempted to make some resistance to their depredations, was killed, and his grandchild had five balls shot through him, but is yet living. Mr. Russel, however, previous to his death, shot one of the ring-leaders. Capt. Warner of the privateer brig Elizabeth, was made prisoner by these ruffians, but got released by giving them two half-joes [Portuguese coins]. This banditti also took off several persons, among whom were Capt. James Green and Ensign John Morris, of the militia.[15]

Into the summer months, Tye and his raiders continued to plague the Patriots, particularly militiamen of Monmouth County:

Ty with his party of about twenty black and whites, took and carried off prisoner Capt. Barnes Smock and Gilbert Van Mater; at the same time spiked the iron four-pounder at Capt. Smock’s house but took no ammunition: Two of the artillery horses, and two of Capt. Smock’s horses were likewise taken off. The above-mentioned Ty is a negro, who wears the title of Colonel, and commands a motley crew at Sandy Hook.[16]

Within two weeks there was a report of another attack, in this case, a much larger raid in Monmouth County along the Raritan Bay:

Yesterday morning a party of the enemy, consisting of Ty with 30 blacks, 36 Queen’s Rangers, and 30 refugee tories, landed at Conascung. They by some means got in between our scouts undiscovered, and went up to Mr. James Mott’s, sen. plundered his and several of the neighbours houses of almost everything in them; and carried off the following persons, viz. Mr. James Mott, sen. Jonathan Pearse, James Johnson, Joseph Dorset, William Blair, James Walling, jun. John Walling, son of Thomas, Philip Walling, James Wall, Matthew Griggs, also several Negroes, and a great deal of stock, but all the negroes, one excepted, and the horses, horned cattle and sheep, were, I believe, retaken by our people.[17]

The interesting thing about this raid was the unaffiliated Loyalist raiders led by a former slave were accompanied by soldiers of the most active Loyalist regiments, the Queen’s Rangers, who at this time were stationed on Staten Island.

In August, another raid in Monmouth County attributed to Col. Tye was the kidnapping of two politically influential Patriots, Lt. Col. John Smock and Hendrick Smock.[18] Adelberg described the implication of these raids in Monmouth County:

By this time, the notoriety of Tye may have broken the spirit of certain militia companies. A return for a class (half a company) of militia drawn up on August 17 shows that only two of seventeen militia men listed on the return—Joseph and Thomas West —responded to the alarm “to March after Colo. Tye.” Tye’s reputation had reached the point that many militiamen were unwilling to face him.[19]

Then in September 1780 came a confrontation between two of the main antagonists in the conflict along the North Jersey Coast: Patriot Capt. Joshua Huddy and Loyalist Col. Tye.[20]

Joshua “Jack” Huddy was an “expelled” Quaker from Salem County, New Jersey, who after the death of his first wife, moved to Monmouth County and in 1778 married a widow, Catherine Hart, the owner of the Colt’s Neck Inn. Huddy was a fanatical supporter of the Patriot cause and in 1777 was appointed a captain of New Jersey State Troops.[21] He participated in the Battles of Germantown in 1777 and Monmouth in 1778, and in 1780 joined with Brig. Gen. David Forman in the formation of the Monmouth Association of Retaliators, who undertook vigilante actions against suspected Loyalists.[22] In August 1780 he received a letter of marque and outfitted his privateer galley, Black Snake. He also had a tumultuous personal life—supposedly he cast out his wife Catherine and his two daughters from his first marriage from her Colt’s Neck Inn and took up with a young woman, Lucretia Emmons.[23]

On September 1, 1780, Colonel Tye and party of Loyalist raiders arrived at Captain Huddy’s compound in Colt’s Neck, Monmouth County.[24] It was thought that, aside from Huddy, a number of Monmouth militiamen were staying there, but this proved to be untrue. It did serve as a depot for militia supplies; in the inn were a number of muskets and a supply of ammunition. A good summary of the attack at Huddy’s tavern in Colt’s Neck is in the Philadelphia Gazette of September 9, 1780:

One of these attempts (and one which very nearly proved successful) was made about the 1st of September, 1780, by a body of Refugees black and white, including among the former the mulatto leader known as “Colonel Tye.” The party made an unexpected attack on Huddy’s house, which was bravely defended by himself and a girl of about twenty years of age, named Lucretia Emmons. The house had been a station for a detachment of the militia, and fortunately the guard had left there several muskets, which the girl now loaded as rapidly as possible and handed to Huddy, who fired them successively from different windows, wounding several of the assailants and causing them to greatly overestimate the number of defenders. This caused them to shrink from further direct attack, and they then set fire to the house, which, of course, ended all hope of successful resistance on Huddy’s part, and seeing the flames beginning to spread, he, to save his house, agreed to surrender on condition that they would extinguish the fire, which terms they accepted.[25]

With Captain Huddy taken prisoner (Lucretia Emmons was released), the party gathered up what plunder they could carry, along with some livestock, and headed for the coast to return to Sandy Hook.

The attack on Huddy’s property aroused the local militia and they began a pursuit of the Loyalists and their prisoner, who were headed for the Shrewsbury River where their boats were hidden.[26] As the militia reached a spot known as Black Point[27] overlooking the Shrewsbury River, they saw the fleeing raiders and opened fire on the boats. In the confusion of the raiders’ flight, somehow Huddy was able to jump overboard and swim to shore, while the Patriots kept up their firing. It was reported that Captain Huddy was heard to shout, “I am Huddy,” but he was nonetheless wounded in the thigh, most likely shot by the militia; he made it to shore and escaped his captors.

As for Colonel Tye things did not work so well: he received a wound in the wrist either at the original encounter at Colt’s Neck or at the Shrewsbury River; it became infected with tetanus, turned gangrenous, and a few days later he died.[28] As for the Black Brigade, its leadership was taken over by another “honorary Colonel” named Stephen Blucke. They continued their raiding, but were not as effective after Tye’s death.[29] As Adelberg noted, “Black Loyalists remained active in raid warfare in New Jersey into 1782. The remaining members of the Black Brigade and their families (49 men, 23 women, 6 children) were resettled in Canada in 1783.”[30]

How does one sum up the life of Colonel Tye and his place in New Jersey’s Revolutionary War history? Franklin Ellis, a nineteenth century historian of Monmouth County wrote that Colonel Tye “was generally acknowledged to be about the most honorable, brave, generous and determined of the refugee leaders. Like our forefathers, he fought for his liberty, which our ancestors unfortunately refused to give him.”[31] Edwin Salter, another nineteenth-century historian from Monmouth County, noted of Colonel Tye’s motives for joining the British:

the history of Monmouth furnishes instances proving that the Blacks were active and valuable aids to the enemy as in the case of the noted Col. Tye and his company. It is no difficult matter to tell why the Blacks aided the enemy—they received their liberty by so doing. The question naturally arises in the mind, ‘Would not our ancestors have gained by freeing Blacks and the securing their aid against the British?’[32]

Finally, Robert A. Mayers, wrote:

Tye’s reputation lived on among his comrades, as well as among his enemies. Many Americans contended that the war at the New Jersey shore would have been won much sooner had Tye been enlisted on their side. Others observed that had he lived on for the rest of the war, it would have been a disaster for the Patriots of Monmouth County. Ironically, Tye and other African-American Loyalists fought against the Patriots not because of their loyalty to the Crown but for many of the same freedoms the Patriots had demanded from the King.[33]

[1]It seems Corlis did not mend his ways, in 1778, he was read out of the Meeting, for aside from his refusal to comply with the request to free his slaves, he was accused of public drunkenness and cursing,

[2]“Pennsylvania Gazette, November 22, 1775.” Documents relating to the colonial, history of the State of New Jersey: Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey for the Year 1775, First Series XXX1, ed. A. Van Doren Honeyman (Sommerville, NJ: The Unionist Gazette Printers, 1923), 220. In some articles and stories, Titus is referred by the term “mulatto,” a person of mixed white and black ancestry, now a sometimes-offensive term.

[3]The British did not commission Blacks in their army; the title Colonel in Tye’s case was an honorific bestowed on him by his men as a respect for leadership qualities.

[4]Michael Adelberg, The American Revolution in Monmouth County: The Theatre of Spoil and Destruction (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010), 85.

[5]John U. Rees, “’I offer freedom to the blacks of all Rebels that join me’: Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, 1775-1776,” American Battlefield Trust, October 16, 2020, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/lord-dunmores-ethiopian-regiment.

[6]For an excellent presentation on Colonel Tye’s life between 1775 and 1779 see Michael Adelberg,“Colonel Tye (1754-1780): Leader of Black Brigade of Loyalist Raiders,”Crossroad of the American Revolution, ed. Larry Kidder, revolutionarynj.org/rev-neighbors/colonel-tye-5/.

[7]Graham R. Hodges, Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey 1665-1865 (Madison, WI: Madison House, 1997), 97.

[8]During the Revolutionary War, Sandy Hook was an island, whereas today it is a peninsula. It was referred to by the Patriots as “a place where horse-thieves resort.” For a good, brief overview of the history of Sandy Hook and its famous lighthouse during the Revolutionary War see Michael Adelberg, “’So Dangerous a Quarter’: The Sandy Hook Lighthouse During the American Revolution,” The Keeper’s Log: Journal of the United States Lighthouse Society (April 1995), 5-10.

[9]Not to be confused with a unit of the British Army known as the “Black Pioneers,” that group was not a fighting unit, rather they performed manual labor activities. The On-Line Institute for Loyalist Studies, royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/blkpion/blkhist.htm.

[10]Hodges, Slavery and Freedom, 98. The term “maroon” in this context refers to the original meaning of the word, a fugitive slave; from Spanish cimarron, a slave who “ran wild.” etymonline.com/word/maroon. Another term describing the activities of these Loyalist raiders was “picarooning: to act like a pirate.”

[11]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey: Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey, vol. III, 1779,William Nelson, editor, (Trenton: John L. Murphy, Publishing, 1906), 454 (NJ Revolutionary Extracts).

[12]NJ Revolutionary Extracts, 504.

[13]Adelberg, The American Revolution in Monmouth County, 85.

[14]Hodges, Slavery and Freedom, 98.

[15]NJ Revolutionary Extracts, 4: 299. “half joes” refers to Portuguese coins called “johannes” and “half-johannes” after the Portuguese King Johannes V. The “joe” was worth around £6 Pennsylvania money before the Revolutionary War.

[16]“Extract of a letter from Monmouth county, June 12,” NJ Revolutionary Extracts, 4: 434-435. This raid took place near Colt’s Neck, New Jersey.

[17]“Extract of a letter from Monmouth county, dated June 22, 1780,” ibid, 456- 457. Consacung (Point) is the present- day Union Beach, New Jersey.

[18]NJ Revolutionary Extracts, 4: 608. They were father (John) and son.

[19]Adelberg, The American Revolution in Monmouth County, 89

[20]For an excellent article on Joshua Huddy see: Matthew H. Ward, “Joshua Huddy: Scourge of New Jersey Loyalists,” Journal of the American Revolution, October 8, 2018.

[21]New Jersey State Troops were militiamen who committed to serve on full-time active duty for a longer term—usually a year; funded and equipped by the state.

[22]The Loyalist hatred of Huddy began with his involvement in the hanging of the Loyalist Stephen Edwards in 1777 followed by a number of others.

[23]In most of the articles about the attack at Colt’s Neck, Lucretia Emmons (later Mrs. Chambers) was described as a “servant girl of about twenty years of age.”

[24]The number of raiders who reportedly accompanied Tye ranges from thirty to as high as seventy-two. Colt’s Neck was part of Shrewsbury Township; some articles say that this was where John Corlis’s farm was located and it was from here that the slave Titus ran away.

[25]Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County, New Jersey(Philadelphia: R.T. Peck & Co., 1885), 214. Hodgesplaces the attack at Toms River, New Jersey, as do other articles that apparently rely on Hodges; this is in error, the attack and capture of Huddy at Toms River took place in 1782. Hodges, Slavery and Freedom, 103.

[26]The distance from where the raiders hid their boats on the Shrewsbury River to Colt’s Neck is around twelve miles.

[27]Today this is in Rumson, New Jersey, located there is the Huddy Park and the Huddy Leap Monument.

[28]As in other areas of Tye’s life there are no official sources of the cause of his death, rather it seems to be accepted that tetanus infection was the reason for his death.

[29]Blucke, from Barbados, originally served with the Black Pioneers. Supposedly he was with the party that attacked Toms River in March 1782, once again capturing Capt. Joshua Huddy, taking him to New York City. From there in April 1782, he was taken to Middletown Point (today Highlands) and hung by the Loyalists. Blucke was among the 3000 or so Black Loyalists who settled in Nova Scotia. Robert A. Mayers, “The Patriot and the Pine Tree Robber: Captain Huddy and Colonel Tye,”Revolutionary New Jersey: Forgotten Towns and Crossroads of the American Revolution (Staunton, VA: American History Press, 2018).

[30]Adelberg,“Colonel Tye (1754-1780).”

[31]Ellis, The History of Monmouth County,114.

[32]Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties(Bayonne, NJ: E. Gardner & Son, 1890), 429-430.

[33]Robert A. Mayers, “The Patriot and the Pine Tree Robber.”

4 Comments

Why was the name “Ethiopian” chosen for the name of this regiment? I have a hard time finding other sources explaining how the Ethiopian Regiment got its name.

Great article showing important Black history. Thank you for writing and sharing.

Dr. Wroblewski,

Thank you for a fine article on Col. Tye. I too have built on Graham Hodges’s work to flesh out more about Tye and John Corlies. I wrote about these two Revolutionary-era figures in my recently published Stories of Slavery in New Jersey (2021, The History Press, Charleston SC). I was able to determine through primary documents, Last Wills, and deeds where the Corlies family and Titus actually lived in Shrewsbury. The contemporary maps of the time usually point to the historic center of Shrewsbury, at the Four Corners (today’s Broad St. and Sycamore Ave.). The Corlies property was on the Rumson peninsula just across from Sandy Hook, making for an easy escape route for Tye.

I’d be happy to correspond with you on this and other aspects of early Monmouth County history.

Best, Rick Geffken

Extremely interesting article and account on the life of Col. Tye, a well respected African American who fought fervently by any means necessary during a pivotal point in history. His life would make for a great documentary!