The story of the Black Haitian soldiers serving in the French army in the battles to wrest Savannah, Georgia, from the British in September–October 1779 went largely ignored until the 1950s and remains incompletely explained.[1] They have become better known, however, than the overall role of the peoples of the Caribbean in the era of the War for Independence.

What began as the American Revolution in 1775 morphed into a British war with France in 1778, and with Spain in 1779. This world-wide conflict centered on the islands of the Caribbean, where slave labor was used to produce sugar, a hugely valuable commodity, to make rum. The French possessions alone had more value than all of the thirteen rebelling colonies. Britain gave priority to defending Jamaica.[2]

Peoples of these islands and Spanish Louisiana and Mexico became contractors, sailors, and soldiers in this war. To that end, in the French colony of St. Dominique (Haiti), on the island of Santo Domingo, on March 12, 1779, Laurent-François le Noir (1743-1798), Marquis de Rouvray, formed ten volunteer African Haitian chasseur (light infantry) companies, each consisting of three officers, fifteen non-commissioned officers, and sixty privates, as two battalions for the French army. Recruiting exceeded expectations by 49 percent and the companies were expanded to include eighty-four men and four corporals each on April 21.

Half of all people in Haiti at the time who were not enslaved were Black. Enlistment was open to all “gens de couleur” (gentlemen of color) not enslaved and to enslaved men, who were offered freedom from bondage for service. Recruits came from across the island and from all classes, including from prominent Black land-owning families. Each company eventually consisted of eighty-eight fusiliers, eight corporals, four sergeants, and a “fourrier” (forager or quartermaster). All officers were white. Overall leadership of the Chasseurs-Voluntaries de Saint-Dominique consisted of a colonel, a lieutenant colonel (Humphrey O’Dunne), a battalion commandant, and an aide-major.

Rouvray was a land owner in the colony who had risen through the ranks of the French army through service in Canada during the Seven Years War.[3] Allegedly Henri Christophe (1767-1820), later king of an independent Haiti, served as one of the two drummers or as a valet. According to one account, he received a battle wound in the fighting around Savannah. Other leaders of the later Haitian revolution also supposedly served in these battalions but documentation is lacking.[4]

Vice Admiral Charles-Henri Hector (1729-1794), the Comte d’Estaing, arrived at Cap-François, the capital of the colony, with sixty-five warships, and an army. His expedition had captured the islands of Grenada and St. Vincent’s from the British and caused the capture or destruction of several British ships. D’Estaing secretly had one more project in mind before carrying out his orders to return to France. To that end, he took on board his fleet the white Haitian Grenadier-volunteers battalion (200 men), Rouvray’s Black volunteers (750 men), and two white companies from Martinique for a total of 1,550 men. D’Estaing’s army also included white French regular regiments from Guadeloupe, Haiti, and Martinique. This army of 3,524 left Cap-François on August 15, 1779 in almost one hundred transports and protected by a fleet of twenty-one ships of the line, nine frigates, three corvettes, and one cutter.

The Admiral was persuaded by Lt. Col. Charles-François Sévelinges (1754-1793), the self-styled Marquis de Brétigny, that the mere appearance of the French army and fleet in Georgia would compel the British garrison there to surrender. On September 4, the French fleet began to arrive off that coast. After reaching Savannah, d’Estaing’s army was joined by American forces of 650 Continental and 750 militia soldiers commanded by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (1733-1810).

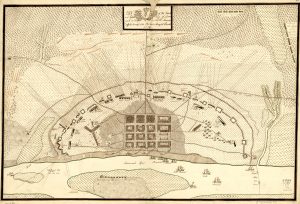

British Brig. Gen. Augustin Prévost (1723-1786) prepared to surrender. The arrival of reinforcements under Col. John Maitland (1732-1779) and the strength of earthworks erected by British engineer Maj. James Moncrief (1741-1793) with Black labor around Savannah, however, persuaded him to make a stand. In all, the British forces in Savannah numbered 3,346 men fit for duty, not including Native Americans and enslaved people, compared to the combined American and French forces of as many as 7,722 men before the effects of sickness and desertion.

The Haitian soldiers, Black and white, were assigned to trench digging, but also did guard duty that consisted of lying down in front of the trenches or behind anything that they could to protect themselves from being shot. The Haitians served in the cold wet trenches under Louis Baury de Bellerive (1754-1807). These earthworks supported the batteries that later failed to reduce the British fortifications.

In the first use of Black Haitians in battle by the French army, Rouvray led his men in repulsing an assault on the French trenches by Maj. Colin Graham and ninety-seven British light infantry before dawn on September 24. Rouvray then made the mistake of pursuing the retreating enemy to within cannon shot of the enemy’s fortifications. Reportedly his men suffered 150 casualties, including 40 men killed running from the cannon fire.[5]

On October 9, the American and French forces were repulsed in a disastrous attack on the British lines around Savannah. Their combined forces lost 244 killed, 600 wounded, and 120 men taken prisoner. Many of the latter proved mortally wounded. British losses came to 40 killed, 63 wounded, and 52 missing. British Colo. John Maitland ordered a bayonet charge against the fleeing disorganized allied forces.

Under Gen. La Vicomte Louis-Marie Marc Antoine d’Ayen de Noailles (1756-1804), and supported by two cannon, the Black Haitian soldiers protected the withdrawal and the French camp as part of a reserve column that also included Marines and two white companies from Martinique. The white Grenadier-volunteers battalion with some of Rouvray’s soldiers served in a feint attack with the American militia that failed to draw British forces away from the main assault.

Reportedly, twenty-five of the Black Haitian soldiers died protecting the panicked escaping mob of American and French soldiers. One French officer claimed that the men of French army would have thrown down their weapons and surrendered if not stopped.[6]

During the campaign, desertions reduced Rouvray’s volunteers to only 545 men and the white Grenadier-volunteers battalion under a Major Des Francais to only 156 men. Guards prevented further desertions from the Black troops.[7]

D’Estaing, wounded in the battle, ordered an end to the campaign. He returned to France a hero with some of his Black Haitian soldiers accompanying him and Rouvray on their arrival at Versailles for an audience with the King. The Savannah campaign almost delayed the second British invasion of the South from New York long enough that it might have never happened and could have avoided what became two of the bloodiest years of the American Revolution.

A company of sixty-two of the Black Haitian soldiers accompanied the wounded to Charleston and were among the soldiers who surrendered when the British successfully laid siege to the city in May 1780. They were subsequently sold into slavery along with their comrades captured by the British at sea. What remained of the Chasseurs-Voluntaries de Saint-Dominique regiment served out the war as garrison troops in Grenada and Haiti. French officials considered forming a permanent regiment of Black soldiers in Haiti but recruitment failed.[8]

The Black soldiers in the Savannah campaign must have raised local concerns. Georgia’s loyalist Royal Georgia Gazette argued that the use of Black soldiers by the French justified General Prévost’s controversial decision to arm enslaved people.[9] George Washington and the Continental Congress had to be persuaded to keep African American soldiers in the Continental army in order to maintain troop strengths and in spite of fear of slave revolts.[10] Of the thirteen original states, only Georgia and South Carolina refused to enlist enslaved people into their Continental forces in return for emancipation, although both states used Black soldiers.[11]

The site of two colonial Jewish cemeteries in Savannah is the only ground on the battlefield that remains as it was in 1779, and marks where the Black Haitian soldiers stood during the battle. Today a monument in the city honors the Black Haitians who served in d’Estaing’s army.

[1]George P. Clark, “The Role of the Haitian Volunteers at Savannah in 1779: An Attempt at an Objective View,” Phylon 41 (Winter 1980): 358-59.

[2]See Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000).

[3]Some secondary sources indicate that the Marquis de Rouvray was Black, but primary sources do not support this assertion. See, for example, Gil Troy, “The Revolutionary Drummer Boy Turned Haitian King,” Daily Beast, February 17, 2018, www.thedailybeast.com/the-revolutionary-drummer-boy-turned-haitian-king; Asa Bird Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France (Providence, RI: Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati, 1905), 32; Stewart P. King, Blue Coat or Powder Whig: Free People of Color in Pre-Revolutionary Saint Dominique (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2007), 67-68; “Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chasseurs-Volontaires_de_Saint-Domingue#cite_note-FOOTNOTELespinasse1882166%E2%80%9367-2; Rita Folse Elliott, “The Greatest Event That Has Happened in the Whole War”: Archaeological Discovery of the 1779 Spring Hill Redoubt, Savannah, Georgia(Savannah, GA: Coastal Heritage Society, 2011), 7, www.thelamarinstitute.org/images/PDFs/publication_175.pdf; Clark, “The Role of the Haitian Volunteers,” 360.

[4]Alexander A. Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah: The Story of Count d’Estaing and the Siege of the Town in 1779 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1951, 1968 revised edition), 15-16, 153n13; Clark, “The Role of the Haitian Volunteers,” 357-58.

[5]Clark, “The Role of the Haitian Volunteers,” 362; David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain’s Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia 1775-1780(Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 250-52, 272-73; Rachel Ernest Dupuy, Gay M. Hammerman, and Grace P. Haynes, The American Revolution: A Global War(New York: David McKay, 1977), 90; Rita Folse Elliott, Daniel T. Elliott, and Laura E. Seifert, Savannah under Fire, 1779: Identifying Savannah’s Revolutionary War Battlefield (Savannah: Coastal Heritage Society, 2009), 70: www.thelamarinstitute.org/images/PDFs/publication_173.pdf. Rouvray may have commanded the left column in the main attack on the British lines. Wilson, The Southern Strategy, 159, 307n83.

[6]Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 91-103; Elliott, “The Greatest Event That Has Happened the Whole War”, 7, 10, 17; Wilson, The Southern Strategy, 150, 159; Elliott, et al, Savannah under Fire, 70, 139, 141; Troy, “The Revolutionary Drummer Boy Turned Haitian King.” Noailles later represented France in negotiating the arrangements for the British surrender at Yorktown. See Edward Martin Stone, Our French Allies: Rochambeau and His Army (New York: Scholars Bookshelf, 2006), 286-88.

[7]Lawrence, Storm Over Savannah, 120.

[8]John D. Garrigus, Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in French Saint-Domingue (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2006), 208-10; Elliott, et al, Savannah under Fire, 227-28; King, Blue Coat, 65-66; Troy, “The Revolutionary Drummer Boy Turned Haitian King.” Rouvray would hold several important posts in France and Haiti after the American Revolution, before the French Revolution compelled him to immigrate to Philadelphia. He died there on July 18, 1798. Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France, 94.

[9]Leara Roberts, “Haitian Contributions to American History: A Journalistic Record” in Doris Y. Kadish, ed., Slavery in the Caribbean Francophone World: Distant Voices, Forgotten Acts, Forged Identities (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016), 83. The British continued to use African Americans as soldiers in Revolutionary War Georgia. Timothy Lockley, “’The King of England’s Soldiers’: Armed Blacks in Savannah and Its Hinterlands during the Revolutionary War Era, 1778-1787,” in Leslie M. Harris, Diana Ramey Berry, and Jonathan M. Bryant, eds., Slavery and Freedom in Savannah (Athens, GA, 2014), 26-41

[10]Patrick F. Moriarty, “The Myth of the Citizen-Soldier: Black Patriots and the American Revolution” (Master’s Thesis, Wesleyan University, 2014), 18; also see Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

[11]See Bobby G. Moss and Michael C. Scroggins, African-American Patriots in the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution (Blacksburg, SC: Hibernia Press, 2004). Georgia granted freedom from bondage to slave Austin Dabney for his service and crippling wounds received in battle despite the state’s laws prohibiting enslaved people from bearing arms or serving in the militia. Dabney became the first black federal or state pensioner and, for almost fifty years, the only African American receiving a pension from the United States government. Robert S. Davis, “Tribute for a Black Patriot: A Pension for Austin Dabney,” Prologue Magazine 46 (Fall 2014): 22-29.

3 Comments

Thank you for this. The Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue and especially Henri Christophe are featured prominently in my Dissertation. My sister lives outside Savannah, and whenever I go to visit her, I try to stop in to pay my respects to the statue. One of my Dissertation subjects was a Drummer in the American Revolution from Virginia.

Thx for this info. I am an African American whose grandfather immigrated from Haiti. Aside from unknown African ancestors I also proudly claim Jamaican, Canadian First Nations and also Scottish heritage. I know abt First Rhode island Regiment (?) But I did not hear abt Haitian soldiers in Rev War until recently and this is most thorough description I have seen.

Did the Chasseurs-Voluntaries carry any colors? Is their any record of a regimental flag?