Editors Note: We first published this article on this date two years ago, but because it is such a good piece and we have so many new readers, we thought it would be appropriate, like any great holiday tradition, to share this inspiring article again this year.

When the two columns of the Continental Army slammed into Trenton at 8 a.m. on Thursday, December 26, surrounding and capturing most of the Hessian garrison, new life was breathed into a faltering revolution. But how did they get there?

In late 1776, Washington’s greatest fear was that a hard freeze of the Delaware River would enable the British to march across and capture the colonial capital at Philadelphia. The river had frozen over lightly on December 23, but had broken up 48 hours later.[1] He also realized that enlistments for many of his troops expired at the end of the year. He and his advisors were cognizant of the need for a bold stroke to revive the war effort. In mid December, the commander-in-chief began to formulate that bold strike—an attack against the 1500 Hessians garrisoned at Trenton. He wrote, “Christmas-day at night, one hour before day is the time fixed upon for our attempt on Trenton.”[2] Washington’s plan called for three coordinated, simultaneous river crossings, with two columns attacking Trenton, while the third provided security against an enemy counter-thrust from the south. Those efforts led by Col. John Cadwalader and Gen. James Ewing below Trenton were mostly unsuccessful.[3]

While many participants wrote of the crossing in letters and memoirs, most soldiers mentioned only the weather or the icy river. Almost nothing seems to have survived about the actual mechanics of the event. I’ve arrived at many of the conclusions in this article after years of studying the literature of the crossing, many visits to the site, and conversations and correspondence with professional and avocational historians. Unfortunately, many of the details of this historic night will never be known.

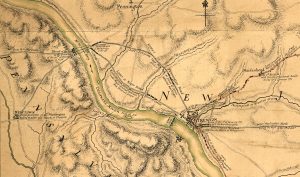

The main element of the Continental Army under Washington was to cross the Delaware above Trenton and then march the approximately ten miles to their objective.[4] This would be a river crossing, not a contested amphibious assault such as the Normandy landing. Given the obstacles encountered, it is amazing that this part of the plan worked as well as it did.

The Delaware River at the point of crossing is estimated to have been between 850 and 1,000 feet wide and between 5 1/2 and 7 1/2 feet deep, with a current of 11 to 12 miles per hour. Richard Paterson, director of the Old Barracks Museum, posits that the river was in flood, rising to the current visitor’s center on the Pennsylvania side and over the current lower parking lot on the New Jersey side.[5] As water was not then removed from the river for other purposes as is now the case, the width and depth were likely greater than today.[6]

Two ferries and their adjacent houses or taverns served the traveling population at this site—McKonkey’s[7] (the lower ferry) on the Pennsylvania side and Johnson’s (the upper ferry, sometimes referred to as John’s, but operated by James Slack) on the Jersey side. As ferries were licensed by the individual states, it was not unusual to have two such ferries in such close proximity with different names. But essentially, this was one ferry crossing, just north of the current bridge. The current stone walls along the bank are later additions, and there were no docks, but rather roads that sloped down to the landing to accommodate teams and wagons as they rolled on or off the ferry boats.

The ferry or flat boats themselves, which were to play a crucial role in the crossing, were usually between 40 and 50 feet long and up to 12 feet wide—large enough to accommodate the freight wagons and teams as well as the smaller farm vehicles that would constitute their regular customers. The boats were flat-bottomed scows with low sides and hinged front and rear ramps. Ferrymen propelled them across the river using cables fixed to the shore and a system of pulleys, ropes, and setting poles.[8]

Mort Kunstler’s recent painting of the crossing clearly shows a cable connected to the ferry, as would have been the case under normal circumstances. However, as part of securing the river crossings, such cables would probably have been earlier cut or simply removed to deny access to the British. Whether they were restrung for Christmas night will likely never be known.

The boats most associated with the crossing are Mr. Durham’s Boats, the work horses of the Delaware. Tradition says that Robert Durham built the first such craft in 1757, to serve the Durham Iron Works in Riegelsville, Pennsylvania. There is, however, no hard evidence to support this, and historian Richard Hulan suggests that the sleek craft were initially developed by Swedish and Finnish river men, not Durham. Either way, by the time of the revolution, perhaps as many as 100 such vessels served as the chief cargo boat on the Delaware, hauling iron, grain, whiskey, and produce.[9] William Stryker estimates the number much lower at 40.[10]

With both a sharp bow and stern, the boats varied in length from 40 to 66 feet, with the average probably about 60 feet, drawing between 20 and 30 inches of water when loaded. The beam was about 8 feet, the hold 3 to 3 1/2 feet deep, and the bottom flat. Eighteen foot oars, iron tipped setting poles, and sails propelled the craft, although there is no record of the latter having been used during the crossing. A 30-foot-plus stern sweep controlled the direction. The captain’s name was usually painted on the hull.[11] The current reproduction boats at Washington’s Crossing State Park in Pennsylvania are approximately 40 feet in length.

The Durham was typically manned by a crew of five to seven. With the captain at the stern sweep, the rest would work the oars or walk the 12-inch wide boards along the gunwales, using the setting poles—much like a keelboat. If weather and current cooperated, a sail could be used.

One observer offered that, “She left the water almost as calm as she found it.”[12] Washington wrote of the boats breaking a passage through the ice.[13] He had first seen these vessels in Philadelphia in 1775. Despite the depiction in the movie The Crossing, Washington did not wait until his retreating army reached the banks of the Delaware to begin collecting the Durhams. As early as December 1, from Brunswick, New Jersey, he wrote to Col. Richard Humpton of Pennsylvania, ordering:

You are to proceed to the two ferries near Trenton and to see all the boats put in the best order, with a sufficiency of oars and poles and at the same time to collect all the additional boats that you can from above and below and have them brought to these Ferries and secured for the purpose of carrying over the Troops and Baggage. . . . You will particularly attend to the Durham Boats which are very proper for this purpose.[14]

Through purchase, hiring, and confiscation, Humpton, with the assistance of Hunterdon County, New Jersey, militia and New Jersey and Pennsylvania river men, did just that. Shortly after, similar orders were also dispatched to Brig. Gen. William Maxwell above Trenton.[15] These craft would first deliver the Continental Army out of harm’s way into Pennsylvania on December 7-8, would then bring that same army back across the Delaware on Christmas night, and finally return soldiers and prisoners back to safety after the victory. They would also be used to return to New Jersey for the second phase of the winter campaign.

The boats were collected not only to transport the army across the river, but also to keep them out of British hands. Most were berthed in Knowles Creek (now Jerico Creek) and behind Malta Island (now connected to the mainland) below Coryell’s Ferry (today’s New Hope, Pennsylvania). Many histories speak of the boats as being “hidden” in these areas. As the British knew that the Americans had cleared the river of all serviceable craft and since there were spies up and down the banks, it seems less likely that they were hidden as much as simply collected in these locations. Plus, trees in December would be bare, offering little foliage for concealment.

On December 19, at Washington’s direction, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene wrote to Brig. Gen. Ewing from Bougart’s Tavern in Buckingham, Pennsylvania:

Sir I am directed by his Excellency General Washington to desire you to send down to Meconkea ferry, sixteen Durham Boats & four flats. Youl send them down as soon as possible. Send them under the care and direction of some good faithful Officer. I am Sir your most obedient & very humble servant.[16]

While this document gives us the number of boats planned for the crossing, we are still uncertain about the exact number, as we cannot determine if the sixteen were actually sent and if McKonkey’s and Johnson’s flats were already on the scene or part of the four mentioned. A safe estimate is sixteen Durhams and four or five flats.

Some writers claim that any available small boat was used in the crossing. This makes little sense, as the artillery and horses would be too big for such vessels and the Durham boats were quite sufficient for the infantry. Plus, manning small craft would be an inefficient use of the experienced mariners, who would be better employed on the larger craft. But there is no way to know for certain. Maybe some small boats were used.

The Durhams and ferry boats would be crewed by the 177 officers and enlisted men of the 14th Continental Infantry, experienced mariners, supplemented by river men from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, who assisted in both the crossing and the landing on the Jersey side.[17] The 14th—Glover’s Marblehead Regiment—were the Grand Banks fishermen who in late August had evacuated the Continental Army across the mile wide East River from Brooklyn to New York. Capt. Alexander Graydon praised them: “There was an appearance of discipline in this corps. . . . Though deficient, perhaps, in polish, it possessed an apparent attitude for the purpose of its institution and gave a confidence that myriads of its meek and lowly brethren were incompetent to inspire.”[18]

Although never mentioned as such, the 27th Continental Infantry, under Maj. Ezra Putnam, was another unit of experienced seafarers who could have also contributed seasoned mariners, as did Capt. Joseph Moulder’s Philadelphia artillery company.

According to Henry Knox, eighteen guns were moved across the Delaware on that historic night. These cannon would be the deciding factor in the battle of Trenton, but would present the biggest difficulty at the crossing. The ferry boats would be critical in moving the guns and their accompanying ammunition wagons safely over the river, with each gun taking as much as an hour to load, secure, transport, and unload. Authors who write of the cannon being moved in the Durham boats are incorrect. They were hauled to the ferry landing and rolled or driven, not lowered, into the flats.

In addition to the men and guns, the critical horses had to be transported. Estimates vary as to just how many animals crossed. Historian Kemble Widmer suggests between 64 and 90.[19] Most other writers make no mention of the topic. My own estimate is a bit higher, broken down as follows: the artillery, 29 to 32; senior officers and aides, 35; Philadelphia Light Horse troop, 24; ammunition carts, 7 to 14. That totals 95 to 105, an estimate at best and perhaps a bit low. Given horses’ difficulty with open running water,[20] moving this many animals over the river would have been one of the major challenges and delays of the night, with estimates that three men were needed to control each horse. The flats would have been used for this purpose, not the Durhams as suggested by some chroniclers.

The weather initially cooperated with the American movement, but eventually turned nasty. The recorded temperature at 3 p.m. was 29 degrees. According to US Naval Observatory calculations, the sun set at 4:40 p.m. on December 25, with the moon rising at 5:31 p.m.[21] The moon had been full the previous day, so there was initially sufficient light to assist the troop movements, with a waning gibbous with 99 percent illumination.[22] Some snow from previous storms lay on the ground.

According to Henry Knox, “Floating ice in the river made the labor almost incredible.”[23] Ice moving from upriver presented a challenge, especially along the shores where passages for the boats had to be broken. The boat crews would battle the floes all night—but successfully.

Weather quotes abound. Sergeant Thomas McCarty said that the 26th was “the worst day of sleet rain that could be.”[24] Knox wrote of a cold and stormy night “that hailed with great violence.”[25] Another writer stated that, “About eleven o’clock at night it began snowing, and continued so until daybreak when a most violent northeast storm came on, of snow, rain, and hail together.”[26] “The storm is changing to sleet and cuts like a knife.”[27] Fifer John Greenwood wrote, “After a while it rained, hailed, snowed, and froze, and at the same time blew a perfect hurricane.”[28] At about 11 p.m., a nor’easter had struck, hiding the moon and considerably hampering visibility. Weather historian David Ludlum describes the events as a cyclonic disturbance that created a storm beginning as snow, but soon changing to a mixture of snow and sleet.[29]

By 2 p.m. on Christmas day, the first troops were in motion toward the river, with all moving by 3 p.m. The brigades of Brigadier Generals Lord Stirling and Roche deFermoy moved down from the north, while Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer’s came from the south. Maj. Gen. John Sullivan’s division of three brigades moved in from the west. Brig. Gen. Adam Stephen’s brigade was already in the area of McKonkey’s. The troops assembled about a mile back from the ferry in the area of the Wright’s Town Road to await darkness. Maj. James Wilkinson said that the, “route was easily traced, as there was a little snow on the ground, which was tinged here and there with blood from the feet of the men who wore broken shoes.”[30]

In total, 28 infantry regiments in seven brigades, seven companies of artillery, and a troop of light horse needed to be moved over the icy waterway. While 2,400 is the usually quoted number of men who marched on Trenton, the actual number is harder to determine. Force’s Archives, William S. Stryker, and Sinews of Independenceall present detailed breakdowns of the troop numbers, and none of them agree![31] One count is as high as 4,500. On December 28, Henry Knox wrote to his wife that “about 2500 or three thousand pass’d the River.”[32] If Knox, who supervised the crossing, was uncertain, it’s unlikely that an exact count will ever be known. Not all men on a regiment’s muster role participated, but only those who were physically able and minimally equipped.

Gen. Greene’s second division crossed first, in the following brigade order: Stephen, Mercer, and Stirling. DeFermoy, who would initially operate independently, crossed next. The three brigades of Gen. Sullivan’s first division followed, Gen. Arthur St. Clair’s first, followed by Col. John Glover’s, and finally Col. Paul Dudley Sargent’s.[33] As soon as darkness partially covered their movements, probably around 5 p.m., the troops marched to the ferry landing, eight men abreast. Each man carried sixty rounds of ammunition and three days rations. Officers affixed a piece of white paper in their hats to mark their rank; and according to John Greenwood, everyone, including officers, carried a gun.[34]

Gen. Stephen’s initial assignment was to secure the landing area on the Jersey side, detaining anyone attempting to either enter or exit the perimeter. This security net would expand as more of his troops landed, eventually reaching a mile beyond Johnson’s Ferry, forming “a chain of sentries round the landing place at a sufficient distance from the river to permit troops to form.”[35] They would also protect the in-progress crossing. Torches and lanterns likely lit the scene once Stephen was across, as maintaining any degree of secrecy would be impossible with 2,400 men and 100 horses involved. There was now no real need or means to maintain silence, although it was mandated. The old military axiom of “hurry up and wait” would have certainly applied.

The larger-than-life figure charged with overall supervision of the crossing and the main architect of its success was Col. Henry Knox, commander of the artillery regiment. Wilkinson wrote of Knox’s stentorian lungs and deep voice that could be heard above the storm’s roar.[36] Col. John Glover was the other prime mover, with responsibility for the boats, and he usually receives due credit along with Knox. Glover was also a brigade commander, responsible for five regiments, so it is impossible to know just where his main efforts lay. Tradition offers that Knox and Ferryman Samuel McKonkey “tested” the water at the start. It’s unclear what that entailed.

Again, tradition suggests that Washington crossed early in the evening on a boat commanded by Capt. William Blackler of the 14th with Private John Russell as an oarsman. There is no evidence as to whether this was a Durham or a flat. There is also an anecdotal story that suggests Knox crossed with Washington.[37]

This raises the vital question of when Knox, with overall responsibility, actually crossed. Again while no documentary evidence exists, Clay Craighead, Senior Curator at Washington’s Crossing State Park in New Jersey, has posited that Knox made a number of trips back and forth across the river to monitor the critical action on both banks. This is a logically reasoned possibility.[38]

So did the troops stand or sit? As with many other aspects of the night, we just do not know. David H. Fischer says that they would not sit due to the slush and icy water in the boat bottoms.[39] But given the Durham’s stability, standing troops could be a problem. Perhaps they stood, squatted, and sat. The ferry boats would also offer all these options.

Washington had hoped for the operation to be complete by midnight, but it quickly fell behind schedule. It was likely the artillery and its wagons and the horses that caused the greatest delay. Subtracting approximately 300 to 400 artillerymen in the seven companies and the light horsemen leaves about 2,100 infantry to move. Using Greene’s number of sixteen boats, each Durham needed to ferry about 130 to 135 men. Taking a low average capacity of 30 to 35 troops, each boat would need to make four or five round trips to move all the infantry. The average crossing time is hard to determine, with estimates ranging from ten to fifteen minutes, although the rough river conditions could certainly have extended the trip. We can, I believe, safely speculate that loading, crossing, unloading, and returning could take an hour for each trip. It’s unknown how wide a front the crossing encompassed—how many boats were crossing at one time and how quickly the next wave pushed off.

Knox later wrote that all the troops were in New Jersey by 2 a.m., without the loss of a man.[40] But a few did take an unwanted swim. Washington stated that the artillery was over by 3 a.m. That means the entire crossing lasted between nine and ten hours, or three hours longer than planned.

An intriguing question is just how difficult was the crossing. With no intention of disparaging the heroic efforts of the boat crews and realizing the icy conditions they faced, this might not have been a particularly arduous task for these experienced mariners and fishermen who regularly plied the stormy Atlantic. This crossing was about one-fifth the length of the earlier East River crossing, also made under difficult weather conditions.

What of the commander-in-chief, after landing in Jersey? According to a suspect “Diary of an Officer on Washington’s Staff,” he stood on the bank wrapped in his cloak supervising the landings. Another account says that he sat on an old beehive, but staff on the New Jersey side can find no such documentation.[41] As the hours passed and the crossing fell behind schedule, he contemplated cancelling the entire operation, but decided, “As I was certain there was no making a Retreat without being discovered, and harassed on repassing the River, I determined to push on at all Events.”[42] He need not have worried. Again Greenwood, “The noise of the soldiers coming over and clearing away the ice, the rattle of the cannon wheels on the frozen ground, and the cheerfulness of my fellow-comrades encouraged me beyond expression, and, big coward as I acknowledge myself to be, I felt great pleasure.”[43] By 4 a.m., with a small rear guard likely remaining at the river to protect the boats, the troops were on the march to Trenton. It is possible that the 260 men of the 6th Battalion of Connecticut State troops under Col. John Chester of Sargent’s Brigade filled this role. They did not march to Trenton. Washington would certainly never leave the critical boats and landing site without protection, for even a small enemy raiding party could have easily torched any unguarded boats.

“Victory or Death!” Dr. Benjamin Rush observed Washington writing this on a scrap of paper before the crossing.[44] With that as the watchword for the night, and after marching the ten miles to Trenton, the army would ultimately capture over 900 Hessians and then re-cross the Delaware using those same boats. The return trip was supposedly more difficult.

At a dinner after Yorktown, Lord Cornwallis toasted Washington with, “When the illustrious part that your Excellency has borne in this long and arduous contest becomes a matter of history, fame will gather your brightest laurels rather from the banks of the Delaware than from those of the Chesapeake.”[45] Certainly well spoken.

[1]David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 398.

[2]Dorothy Twohig, editor, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 7 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 423.

[3]There are many comprehensive studies of the Trenton campaign that detail Washington’s plans. The best are Fischer (see above); William S. Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1898) and subsequent editions; Samuel Stelle Smith, The Battle of Trenton(Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1965); William M. Dwyer, The Day Is Ours! (New York: The Viking Press, 1983); and William L Kidder’s Ten Crucial Days (Lawrenceville, NJ: Knox Press, 2018).

[4]See Fischer, 403, for the best description of distances and routes.

[5]George Athan Billias in General John Glover and his Marblehead Mariners (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1960), 8, says 1,000 feet. The late Harry Kels Swan of New Jersey’s Washington’s Crossing State Park, a long time scholar of the campaign, estimates the river was 850 feet. Conversations with Swan and Richard Paterson.

[6]Paul Taylor, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, email, November 15, 2000

[7]McKonkey’s Ferry is referred to in the historical records as both McKonkey and McConkey, although McKonkey’s appears to be the more used designation during the revolution.

[8]Jack Davis, “Crossing the Delaware—Before Washington,” Hopewell Valley Historical Society Newsletter, Vol. XXV, No. 3, Winter 2007, 484-485.

[9]The best description of the Durham boats is Marion V. Brewington’s “Washington’s Boats at the Delaware Crossing,” American Neptune, Vol. 2, 1942, 167-70. Also very useful are “History of the Durham Boat,” Durham Township Historical Society web site DurhamHistoricalSociety.org/history2.html; and Frank Dale, Delaware Diary, Episodes in the Life of a River (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 32-40.

[12]John A. Anderson, “Navigation of the Upper Delaware, A Paper Read before the Bucks County Historical Society,” Doylestown, PA, 1912, 18.

[13]Papers of George Washington, Vol. 7, 450.

[16]Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Vol. 13 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 712. Greene’s order concerning the boats was initially reported by W.W.H. Davis in an 1880 article in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. It then apparently disappeared from historical view for 100 years, resurfacing in 1984, when it was rediscovered purely by accident. While Davis dated the document Dec. 10 (the writing on the document is blurry), the editors of the Papers of Nathanael Greene verified the authenticity of the letter and confirmed the date as Dec 19, which makes more sequential sense.

[18]Alexander Graydon, Memories of His Own Time, with Reminiscences of the Men and Events of the Revolution (Philadelphia, 1846), 149.

[19]Kemble Widmer, “A Severe Ordeal,” unpublished paper, the Swan Historical Foundation, 1995, 11. I wish to thank my friend Clay Craighead of New Jersey’s Washington’s Crossing State Park for years of good conversations, outstanding assistance, and great observations about the crossing and for providing a copy of Kemble Widmer’s paper. Although I do not agree with all of that author’s conclusions, this is one of the finest examinations of the topic available.

[21]US Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department, http://mach.usno.mil/cgi-bin/aa_pap.pl.

[22]Dr. Donald Olson, astrophysicist, Texas State University, email correspondence, Dec. 2000.

[23]Francis S. Drake, Life and Correspondence of Henry Knox: Major General in The American Revolutionary Army (Boston, 1873), 36. This and what follows are from a Dec. 28, 1776, letter from Knox to his wife describing the crossing and subsequent action at Trenton.

[24]Jared C. Lobdell, editor, “The Revolutionary War Journal of Sergeant Thomas McCarty,” New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings, January 1964, 41.

[26]Frank Moore, compiler, Diary of the American Revolution, Vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner, 1859), 365.

[27]Stryker, 362. This is “From Diary of an American Officer on Washington’s Staff.” Dated Dec. 26, 3 a.m, it is somewhat suspect. The description is still accurate.

[28]John Greenwood, A Young Patriot in the American Revolution: The Wartime Service of John Greenwood 1775-1783 (Westvaco Corporation, 1981), 80. Written by Greenwood in 1809, first published in 1922.

[29]David M. Ludlum, The New Jersey Weather Book (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1983), 206.

[30]James Wilkinson, Memoirs of My Own Times, Vol. 1 (Philadelphia, 1816 and reprint 1973), quoted in Dwyer, 231.

[31]Force’s American Archives, series 5, vol. 3, 1401-02; Stryker, 351-58; Charles H. Lesser, editor, The Sinews of Independence: Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 43.

[33]Papers of George Washington, Vol. 7, 436.

[35]Papers of George Washington, Vol. 7, 436.

[37]Howard Fast, The Crossing (New York: Pocket Books, 1971), 135-6.

[38]Conversations with Clay Craighead, Washington’s Crossing State Park.

[41]Stryker, 362. Nancy Ceperley is the historian at the Johnson Ferry House.

[42]Papers of George Washington, Vol. 7, 454, in a Dec. 27, 1776 letter to John Hancock.

[44]Benjamin Rush, Autobiography, George W. Corner, editor, Princeton, 1948, 124.

[45]George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of George Washington, 1859, 250-51. These writings by Washington’s step-grandson and adopted son should be viewed with caution. In a recent email, Ian Saberton, the editor of the Cornwallis Papers was unable to verify this quote from Cornwallis. But he did offer that it was in the style of Cornwallis and sounded right.

24 Comments

Thanks for a great article that allows one to better visualize and understand this event. I guess the first group across and unknown to Washington was the raiding party authorized by General Stephen. Has a consensus been reached regarding the activities of this group? (Who, what, and when)

Thanks for this. Fresh topic, refreshing insights.

Thanks for reminding us so vividly that freedom isn’t free.

Fascinating and informative. Must read again, and again, and again!

Very interesting article Bill. You have helped those of us who have not focused on Trenton with an excellent discussion of what is known and not known about this event. One of my favorites!

Bill, Informative, thoughtful and well researched article. Appreciate the focus on the practical aspects of how Washington pulled of this difficult, but not impossible crossing. Reminds us of the importance of thinking ahead, providing good guidance to subordinates then allowing them to execute difficult tasks. Washington clearly had some men he could rely on to accomplish what others may never consider. I’m sure you remember METT-T, mission, enemy, terrain and weather, time, troops available. Washington understood this concept, before we ever coined this acronym, and considered and thoroughly addressed each of these elements. Also, reminds me of what one of our Marine Corps generals told me many years ago, sometimes we need a little bit of luck. Merry Christmas and Semper Fi.

Excellent, captivating article!

I have always wondered if deterimination, skill or just impossible conditionss doomed the other two crossings. Washnington’s column faced the same river conditions and were able to cross, albeit, slower than planned. There is not as much historian focus on why the other crossings were unsuccesful.

Fortunately for American independence, Trenton is an example of Washington’s highly complex battle plans that emphasized redundancy to help secure victory.

I thoroughly enjoyed this article. I would urge readers to visit Washington Crossing and view the crossing site as suggested by the museum that is at that location. An added bonus is you could also visit the David Museum of the American Revolution that is a few short minutes from this site. If there is anything you want to see in researching the Revolution, chances are you can find what you need at the David Museum. If you can’t find it, the excellent staff there will gladly assist you with whatever you may need. I can’t wait to return!

Good article.

Excellent article William,

Your style in researching “the crossing” was thorough. It’s surprising what new “things” can be learned by carefully surveying the site with a “boots on the ground” approach.

Gents,

Thank you very much for the kind comments. They are much appreciated. I’ll attempt to answer a few of them.

Pat, when I do Trenton tours, I always stress how Washington thoroughly planned the operation and just how lucky he was. I try to give examples of how things could have gone wrong. Yep – luck is important. Semper Fi to you, too.

Gunter, when Washington ran into the previous day’s revenge raiding party, he was furious with Stephen. That was just part of a rather long chain of events going back to the French and Indian War and would ultimately result in Stephen’s dismissal from the army for drunkenness. That story certainly deserves JAR article. My good pal the late Harry Ward, in his Adam Stephen bio, correctly identifies the leader of that party as Captain George Wallis (p 278). Fisher also explains it in his book (pp 232 + 423) and gives Harry credit. While it’s questionable that they tallied any enemy dead on Christmas Day, I believe that the main thing the patrol accomplished was in making the Hessians a bit more confident that they had repulsed the predicted American attack. Here luck comes in. As an aside, Harry wasn’t a big Washington fan.

Gene, there appears to be much less reliable information about the two unsuccessful crossing. The river is wider at those points, and there would have been more of an ice problem. A number of us who have looked at the crossing can’t locate any info about what boats, besides some possible ferries, were used. It seems that there should have been some Durhams collected on the river below Trenton that could have been used. But not for certain. Plus, Cadwalader and Ewing didn’t have Glover’s men to assist, but there probably were other river men to help. Some made it across, but the artillery didn’t. Ewing’s proposed landing area was right near the stadium where the Trenton Thunder play. I suggest that Ewing’s failed crossing was another piece of luck. Had he been successful, I think there was a good possibility that he would have been spotted by the Hessians, as this force was much closer to Trenton than was Washington’s. Rall would have been alerted and perhaps able to control the high ground along the Assunpink (now gone). That would have made Washington’s attack much more difficult. Just my guess. Gene, I do enjoy your work on the Continental generals, another favorite of mine. Thanks for that.

I’m always happy to learn any new info about Trenton. I also suggest Larry Kidder’s about to be released Ten Crucial Days: Washington’s Vision for Victory Unfolds. He did a great job.

Bill

Nice to read so many positive comments about my friend, Bill Welsch’s article on the crossing of the Delaware and its impact on the battle of Trenton. His talk on the crossing was very well received at our annual conference on the American Revolution in Williamsburg last March. Bill was not on the program, but was in the bull pen, in case a scheduled speaker had difficulty attending. For the first time that happened in 2018 due to illness. Bill stepped on to the mound and threw his “Crossing the Delaware” pitch right down the middle of plate. Nice to see that so many other folks can now read about his research and analysis.

First class article by Bill. With his detailed research and solid supporting references, he’s set a new standard for future JAR writers to follow. And it’s timely reminder (as the meme goes) that “Americans are willing to cross a frozen river to kill you. In your sleep. On Christmas.”

Well done, Bill! Stryker would be proud. Looking forward to seeing you and the other ‘usual suspects’ at this year’s upcoming AmRev conference in Williamsburg on March 22-24, 2019.

Great article. Living in NJ, I am always researching the Battles of Trenton. During Christmas break I visited the colonial era Walnford farm and mill site in Upper Freehold, NJ (about ten south of Trenton). Captain John Polhemus of Monmouth County destroyed the bridge over Crosswick Creek at Walnford to slow the Hessian retreat from Trenton. A young boy at the Walnford farm watched three Hessian officers try to cross the creek on horseback and one fell off his horse. Fifty years later the creek was damned for mill repair and the young boy now an older man searched the area where the Hessian fell and located a spur. The spur and family letter of the event is on display in house.

These days (late 2020 on the eve of Christmas Day) of Brexit needed a lift and this article certainly has provided it! Well done and thank you so much. Perhaps, now that the UK has recovered it’s much vaunted sovereignty, we can read more of the lessons from history so ably provided by your pages.

After the “Christmas Story”, THIS is required reading for EVERY Christmas Day. What a great recap and remembrance. Especially in the midst of stormy days that abound. As stated in a previous year’s comments, a reminder that freedom is never free. Well done, Sir !

Thoroughly enjoyed rereading this piece on Christmas Night. Reaffirms just how remarkable an event this really was in the history of the American Revolutionary War. The British may have downplayed the battle and American victory at the time, but Cornwallis’s toast to Washington after Yorktown confirms that that initial assessment was a bad mistake.

I never tire of hearing about the sacrifices made by our forefathers.

My research shows that Col. Loammi Baldwin commanded the 26th Continental Regiment and was part of the crossing as part of General Sullivan’s brigade but his name is not mentioned here. Are you aware of any such connection or are you sure that the three you mention are the only other regiments that were under the command of General Sullivan?

Peter, here’s my answer. Thanks for the question.

Hi Peter,

Yes, Col Baldwin did command the 26th Continental Regiment and did cross with Washington. But you’re a bit confused with unit terminology. There were three brigades in Sullivan’s division: St Clair’s, Sargent’s, and Glover’s. I mentioned these. Baldwin’s was one five regiments in Glover’s brigade. I didn’t get into regiments. So, the 26th was certainly there, one of 14 regiments in three brigades in Sullivan’s division that marched on Trenton.

I have read that 2 of Washington’s men froze to death during the march. Is this true or does it belong to another incident?

Hi Therese,

I’ve read this, too. But some accounts say that nobody froze during the march. The fact is, we don’t know for certain, but I would guess that’s it’s likely, given the weather and circumstances. One soldier wrote that he certainly would have had he not been awaken. Wish I knew more.

Daniel Olds, Sergeant in Captain James Dana’s Co., of Col. Ward’s Regiment states in his pension declaration that they had one man killed in his company “after we drove the enemy out of town” (Trenton) by the name of Jesse Curtiss.