It took only a few moments for the British works and their military supplies to go up in smoke. The British had just purchased 300 tons of hay as well as 275 sheaves of oats from local farmers on Long Island to support their large garrison around the City of New York. The British were forced to rethink their plans when they received word that all 300 tons of hay had been burned by a certain Major Benjamin Tallmadge of the Continental Army.[1]

In late October 1780, after receiving the hard blow of Benedict Arnold’s treachery, Benjamin Tallmadge returned to Westchester County, New York, to continue his “former scheme of annoying the enemy.”[2] Before long, Tallmadge’s agents sent him intelligence concerning the nearly-finished Fort St. George, also known as the Fortress at Smith Manor, on the south shore of Long Island. Having determined this was an optimal place to launch an attack, Tallmadge sent a letter to George Washington appealing for permission to raid the fort. Despite the fact that Washington denied him permission, Tallmadge believed that neutralizing this fort would prove to be extremely helpful.

To gather more intelligence about the fort, Tallmadge crossed Sound and infiltrated Long Island. He returned with the information that the British completed Fort. St. George, and it contained a reserve of arms, dry goods, and forage.[3] Tallmadge also received notice from his informant, Caleb Brewster, that the British had recently stockpiled three hundred tons of hay in the small town of Coram, a few miles away from the fort.[4] With this new-found knowledge, Tallmadge wrote to Washington on November 7, 1780, appealing again for permission to attack.[5] Upon learning these new details, Washington gave his consent to attack the fort and burn the hay.[6]

Having procured several ships to take them across the Sound, Tallmadge’s dismounted dragoons arrived at Fairfield, Connecticut, on the evening of November 18. Despite his eagerness to take the fort, Tallmadge found it prudent to wait until the weather calmed down enough to safely cross the sound. On the evening of the 21st, Tallmadge’s two companies, totaling eighty men, embarked in eight boats to cross the Sound and launch the ambush on Fort St. George.[7]

Around eight o’clock in the evening, Tallmadge’s men landed at a place called Old Man’s, presently called Mount Sinai Harbor or Cedar Beach. After leaving twenty men with the boats under Captain John Shethar, Tallmadge and his men began their march across Long Island but turned back when the weather proved unfavorable. The next evening around seven they set out for the second time to the south side of the island and halted two miles away from Fort St. George at South Haven.[8] Tallmadge wrote in his report back to Washington after the raid:

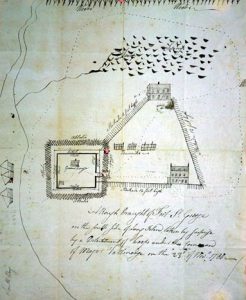

By the most accurate information I found . . . the garrison consisted of fifty men . . . The works of Fort St. George consisted of two large, strong houses, and a fort about ninety feet square, connected together by a very strong stockade . . . the whole forming a triangle, the fort and houses standing in the angles. The fort consisted of a high wall and a deep ditch, encircled with a strong abatis, leaving but one gate . . . This fort had embrasures for six guns, though two were mounted; the houses were strongly barricaded.[9]

With this intelligence, Tallmadge concluded that the best way to take the fort was to divide his small force into three detachments led by Lt. Thomas Jackson, Lt. Calebt Brewster, and Major Tallmadge with Capt. David Edgar by his side. Lieutenant Jackson took sixteen men and crept as close to the fort as possible without being noticed.[10] Tallmadge gave them orders to keep concealed until the enemy fired on the detachment under his command.[11] The men of Lieutenant Brewster’s detachment were the pioneers, carrying axes and hatchets to break down the barricade so Tallmadge’s detachment could enter the fort. Tallmadge created a smaller division to surround the house, keeping the British soldiers from escaping. He ordered the men to keep their muskets unloaded as the element of surprise was necessary for success. The troops were in motion exactly at four o’clock in the evening. Tallmadge’s platoon crouched within twenty yards of the stockade before the British spotted them. “At this moment,” Tallmadge stated, “the sentinel in advance of the stockade, halted his march, looked attentively at our column, and demanded, ‘Who comes there?’ and fired. Before the smoke of his gun had cleared his vision, my sergeant, who marched by my side, reached him with his bayonet, and prostrated him.”[12]

At this, the other detachments rushed forward, and Brewster’s pioneers penetrated the stockade wall. Tallmadge’s men stormed the fort and the American rear guard came behind them to block the exit. When Tallmadge’s men entered the stockade, they charged immediately at the main fort and took it within ten minutes. The watchword, “Washington and Glory!” echoed around the fort, declaring the victory.[13]

A volley of musket fire from one of the houses put an abrupt end to the cheering. A division of the British force had fled into the houses and barred the door. With the help of Brewster’s pioneers, Tallmadge’s men broke down the door and killed or captured the rest of the British force.

The Americans spotted a ship directly off the coast. Tallmadge’s men captured and boarded it. Once they had gathered the reserve of supplies stored in the ship and the fort, they set fire to both the boat and the stockade and demolished as much as they could. As the sun rose Tallmadge and his men headed back to the coast with their prisoners, carrying bundles of dry goods taken from the fort.[14]

Captain Edgar marched the bulk of Tallmadge’s men across the island while Tallmadge and ten others used horses taken from Fort St. George to ride to Coram, where the British had stockpiled three hundred tons of hay. Tallmadge’s squadron defeated the soldiers guarding the hay and burned all of it. Tallmadge and Brewster got back to the main force within two hours. By four o’clock, the battalion reached the shore and, once loaded into their boats, they set off to return to Fairfield.[15]

Not a single one of Tallmadge’s men died, and only one of them left the battle wounded. Seven enemy soldiers died or were terribly wounded. The captives included a lieutenant colonel, a captain, a lieutenant, a surgeon, fifty rank and file soldiers and the garrison’s standard.[16] Tallmadge sent the prisoners to West Point.

Tallmadge remarked in his report to Washington that, “the Officers and Soldiers of the Detachment under my Command behaved with the greatest fortitude [and] Spirit, as well by sustaining the fatigues of so long a march, as storming the Enemies’ Works.”[17]

Later, both Washington and Congress commended Benjamin Tallmadge for his heroic work at the battle of Fort St. George.[18] In his memoir Tallmadge said, “No person but a military man knows how to appreciate the honor bestowed when the Commander-in-Chief and the Congress of the United States return thanks for a military achievement.”[19]

[1]Letter, bill for hay purchased by the British, General Spencer, longwood.k12.ny.us/cms/One.aspx?portalId=2549374&pageId=5741641.

[2]Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge. Prepared at the Request of His Children (New York: Thomas Holman, 1853), 39.

[3]Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, 39-40.

[4]Caleb Brewster to Benjamin Tallmadge, November 6, 1780, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, www.loc.gov/item/mgw426085.

[5]Benjamin Tallmadge to George Washington, November 7, 1780, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence www.loc.gov/item/mgw423114.

[6]George Washington to Benjamin Tallmadge, November 11, 1780, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence,www.loc.gov/item/mgw426119.

[7]Tallmadge to Washington, November 25, 1780, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, www.loc.gov/item/mgw426284.

[8]Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, 40.

[9]Tallmadge to Washington. November 25, 1780.

[11]Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, 40.

[13]Tallmadge to Washington. November 25, 1780.

[14]Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, 41.

[15]Tallmadge to Washington. November 25, 1780.

[16]Enclosure byThomas Frederick Jackson in Tallmadge to Washington. November 25, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04059.

[17]Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, 42.

[18]Order Recognizing Merit of Benjamin Tallmadge, December 6, 1780, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Congress, www.loc.gov/item/mgw426358/.

4 Comments

A captivating account of a textbook raid! Other remote British garrisons must have felt very exposed to similar fates.

This story is corraborated by letters in the Washington Papers, but I have some doubts about the (fanciful) tales in the Tallmadge memoir, since it was published so long after he died. Does it still exist in a manuscript form somewhere?

In many ways you’re right. Figuring out what is fact and what is fiction is very difficult. I have not been able to find a full handwritten manuscript of his memoir as of yet but I have found a few pictures of a couple pages.

His memoir was written in 1830. Tallmadge died in 1835 and it was published by his son in 1858.

I believe that this memoir is trustworthy but we should always fact check it with other historical documents of that time.

A well-formed account! Great reading! (friend of Marge and Stu Ensinger)