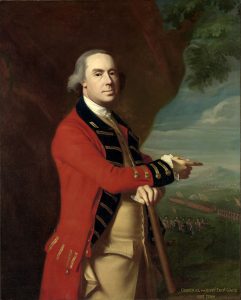

It was late 1775, and William Legge, the 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, was looking out the window of his office in Whitehall, London, thinking of his enemies on both sides of the Atlantic. His letters were partly responsible for the outbreak of open warfare in America. Now a sarcastic poem in a London newspaper was serving as the writing on the wall, mocking his failure to quell the rebellion in the colonies. The words flying back and forth were having deadly consequences, for solders and for careers alike.

Lord Dartmouth had assumed the title Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1772.This cabinet position had been created in 1768 to deal with the increasingly restive North American colonies, and Dartmouth took up the role under his stepbrother, Prime Minister Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford. Faced with mounting problems in the colonies, Dartmouth had at first adopted a policy of conciliation, hoping that tensions would abate. But the Boston Tea Party of December 1773 and other protests had made that policy impossible. Dartmouth sought to reimpose strict British control by supporting the Intolerable Acts of 1774, which led to more unrest. As the situation worsened, Dartmouth still hoped for peace, but prepared for war. While he worked on a secret, last-ditch reconciliation plan with Benjamin Franklin,[1] Dartmouth put contingencies in place, including a covert plan to recruit Loyalists in New York and North Carolina.[2]

By early 1775, Dartmouth was feeling the pressure. On January 20, he presented to Parliament an intelligence report regarding the disturbances in North America, containing some information that had been kept private for eight weeks. Members of Parliament accused the ministers of downplaying the situation to the public by implying that the unrest was confined to Boston only, and not brewing throughout the colonies.[3]

Dartmouth made a fateful decision a week later. On January 27, he wrote a secret dispatch to Gen. Thomas Gage, the British commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, and the military governor of Massachusetts.In it he ordered Gage “to arrest and imprison the principal actors & abettors in the Provincial Congress” in Massachusetts, a group that Dartmouth called “a rude Rabble without plan.” Dartmouth made his meaning plain, advising Gage to“Upon no account suffer the Inhabitants of at least the Town of Boston to assemble themselves in arms on any pretence whatever, either of town guard or Militia duty.” Dartmouth then concluded by giving himself plausible deniability should anything go wrong: “It is understood, however, after all I have said, that this matter which must be left up to your own Discretion to be executed or not as you shall, upon weighing all Circumstances, and the advantages and disadvantages on one side, and the other, think most advisable.”[4]

Gage did not receive Dartmouth’s letter until April 14. He acted promptly, though, and on the afternoon of April 18 Gage issued orders that 700 troops were to assemble during the night for a mission to seize arms stored by the colonial militia at Concord, Massachusetts.[5] Early the next morning the force marched through the town of Lexington and fired upon colonial militiamen assembled on the town green. During the afternoon Gage’s troops were swarmed by Patriot minutemen, who engaged them in a desperate running battle from Concord back toward Boston. The British suffered 73 killed, 174 wounded, and 53 missing.[6] The situation in the colonies had finally tipped into open warfare.

In response to the fighting, thousands of colonial militiamen converged on Boston, besieging Gage’s troops. On June 17, the British assaulted the Patriot positions on Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill on Boston’s north side, suffering over 1,000 casualties for little in return. Gage wrote a dispatch to London, notifying Lord Dartmouth of the ugly results of the battle. Three days after this report arrived in England, Dartmouth replied with an order recalling Gage and replacing him with Maj. Gen. William Howe. Influential men within the government had been arguing for Gage’s removal even before the disaster at Bunker Hill, so the decision was an easy one for Dartmouth.[7] Gage received the order in Boston on September 26, and set sail for England on October 10, never to return to America.[8]

Dartmouth had sacrificed Gage as a scapegoat. But it was too little, too late, and Dartmouth had a target painted on his back as well. The political backstabbing spilled into the public eye again.

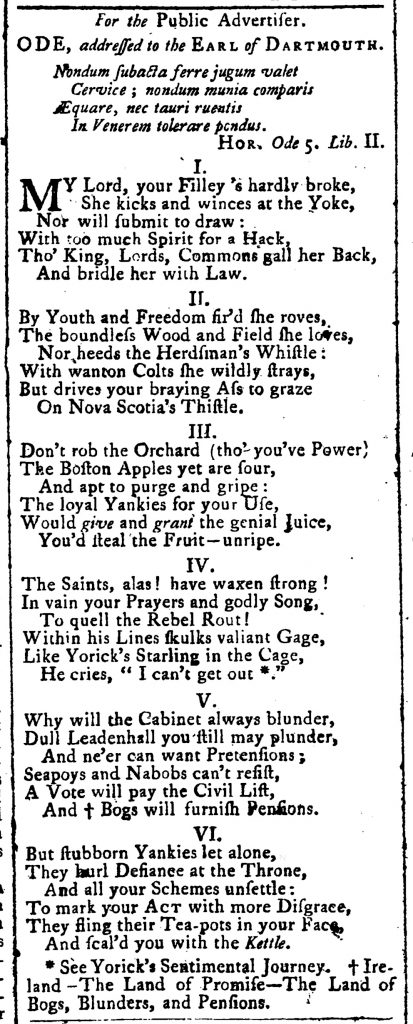

On October 31, 1775 an anonymous poem appeared in The Public Advertiser, a London newspaper that specialized in politics.The “Ode Addressed to the Earl of Dartmouth” was cutting – a reminder that the British press could publish pointed criticism of the king’s ministers, if not of the king himself. The ode pilloried Dartmouth, compared the colonies to a horse he had failed to tame, and made fun of how Gage has been trapped at the Siege of Boston:

History does not record whether Dartmouth read the poem. But ten days later, politically wounded and personally unwilling to direct the war, Dartmouth resigned his position as Secretary of State for the Colonies. He traded it for the position of Lord Privy Seal, which kept him in the Cabinet but away from any responsibility for conducting the war.[9]

Dartmouth’s stepbrother Lord North held onto office through the war. But the Patriot victory at Yorktown in 1781 brought down North’s government, Dartmouth included. Dartmouth lived until 1801, outlasting The Public Advertiser, which went out of business in 1794.[10]

[1]Bob Ruppert, “The Earl of Dartmouth: Secretary of State for the Colonies, Third Year: August 1774-November 1775,” Journal of the American Revolution, January 15, 2019, https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/01/the-earl-of-dartmouth-secretary-of-state-for-the-colonies-third-year-august-1774-november-1775/

[2]Allan J. McCurry, “The North Government and the Outbreak of the American Revolution,” Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 2 (1971): 146, 154.

[3]Cobbett’s Parliamentary History of England, ed. William Cobbett (London, Printed by T.C. Hansard, 1806-20), 18: 148-151.

[4]Earl of Dartmouth to Thomas Gage, Whitehall, April 15, 1775, “Military Affairs Against the Rebels.” Public Records Office, Colonial Office, Class 5: America and West Indies, Volume 92: Military Correspondence of the British Generals October 1774-December 1775, 0660. Library of Congress transcripts; John Richard Alden, General Gage in America (New York: Louisiana State University Press, 1969), 233-41; McCurry, “The North Government,”151.

[5]The initial deployment was 700; additional British troops were later dispatched in support. Donald Barr Chidsey, The Siege of Boston: An on-the-scene Account of the Beginning of the American Revolution (New York: Crown, 1966).

[6]Coburn recounts the by-company British losses, including those missing in action, from Gage’s after-action report. Frank Warren Coburn, The Battle of April 19, 1775: In Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville, and Charlestown, Massachusetts: Second Edition Revised and with Additions (Lexington, MA: The Lexington Historical Society, 1922), 159-160.

[7]Alden, General Gage in America, 281.

[8]Dictionary of Canadian Biography, volume IV (1771-188), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gage_thomas_4E.html

[9]National Archives of Great Britain. “Certificate of Lord Dartmouth’s oath as keeper of Privy Seal,” November 10, 1775. Retrieved from: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/6502aa64-88d4-43c3-ad94-21d12fa7a199

[10]“The Public Advertiser,” https://www.worldcat.org/title/public-advertiser-or-political-and-literary-diary/oclc/186555332

2 Comments

Lord Dartmouth had put himself figuratively between a rock and a hard place. He wanted to please an English ministry that saw protest acts as akin to treason yet he attempted to cultivate friendships with patriot leaders such as Franklin. In my mind, the policy of benign neglect which had been a mainstay of British policy for many years now contributed to this situation. Since he cast his fate to those who wanted to subdue the rebellious colonies, his place in history had been sealed. An excellent piece of writing by Greg Aaron.

Thank you, Andrew. Lord Dartmouth was in a difficult spot, to be sure. Among the factors he was balancing was the opinion of King George III himself. By 1774 the king was disinclined to give the rebels much slack, worried that if the American colonies broke away, there would be disaffection across the empire. In 1775, the post of Secretary of State for the Colonies became one of the worst jobs in the world — partly because of Dartmouth’s actions, and partly because of larger forces beyond Dartmouth’s control.