In my study of Major General Charles Lee, who commanded Continental Army troops at the fascinating Battle of Monmouth Court House, I argue that his post-battle convictions for failing to attack the enemy and for an unwarranted retreat were unjustified. I further argue that most of the blame for the retreat should have fallen on brigadier generals Charles Scott and William Maxwell, who retreated without orders, thereby removing from the field more than half of Lee’s force.[1]

Another Continental Army officer who retreated without orders was Col. Henry Jackson, who commanded about 200 Massachusetts Continentals at the battle.

The record of Lee’s court-martial allows the historian to derive crucial details about Monmouth from testimony taken only a few days after the battle.[2] Jackson’s retreat was covered not only at Lee’s court-martial trial, but also in a separate court of inquiry held in mid-1779.[3]

Dr. James Thacher, of Plymouth, Massachusetts, a regimental surgeon, described Jackson’s detachment as well uniformed and disciplined, and “not inferior to any in the Continental army.” According to Thacher, it had on one occasion marched more than forty miles, from Providence to Boston, in twenty-four hours—in the pouring rain.

As for the thirty-one-year-old Henry Jackson of Boston, and his officers, many of who were sons of prominent Boston merchants and lawyers, Thacher wrote:

He is very respectable as a commander, is gentlemanly in his manners, strongly attached to military affairs, and takes a peculiar pride in the discipline and martial appearance of his regiment. Many of his officers are from Boston and its vicinity; they appear in handsome style, and are ambitious to display their taste for military life and their zeal to contend with the enemies of their country.[4]

Still, Jackson’s detachment was dogged by rumors that it had avoided combat during the Battle of Monmouth Court House on June 28, 1778. The rumors swirled as Washington’s army after the battle proceeded northwards, finally settling at and around White Plains, New York. Jackson’s detachment was then ordered to join a division under the Marquis de Lafayette to march to Rhode Island, where American and French forces were preparing for a joint operation to try to seize British-held Newport.

The proud junior officers of Jackson’s detachment could not bear the stain on their reputations. The day after their arrival in Rhode Island, July 26, sixteen of them petitioned the commander of the Rhode Island theatre, Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, asking him to hold a court of inquiry. They were led by Lt. Col. William S. Smith, the future son-in-law of John Adams and second-in-command of Jackson’s detachment. The petitioners complained that “many gentlemen of General Washington’s army have freely delivered sentiments unfavorable” about the conduct of Jackson’s detachment at Monmouth. The officers accused their colonel of “misconduct, confusion & disobedience of orders.”[5] With a major campaign looming, Sullivan deferred the matter.

What had occurred at Monmouth that led Jackson’s junior officers to challenge him so openly?

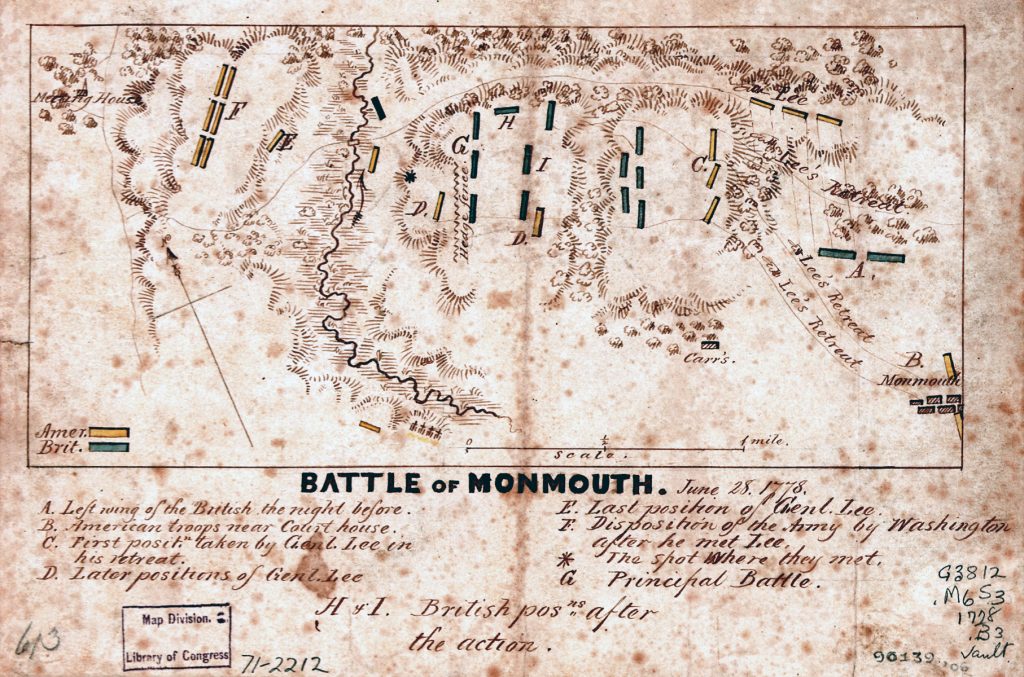

In the morning of June 28, General Lee ordered his troops to march from their camp at Englishtown, New Jersey, towards the village of Monmouth Court House, some six miles away. It was an insufferably hot day, perhaps the hottest weather in which any battle was fought during the war. Lee’s Continentals had to cross first the West Morass and then the Middle Morass, both with deep ravines, difficult terrain for a retreat.[6] Jackson’s detachment started out in the rear of the column but was then ordered to advance to the front.

At about 10 a.m., after crossing the Middle Morass, Lee’s troops emerged from woods. In the distance, they could see Monmouth Court House, and to its right on a rise, a rear guard of about 600 enemy soldiers. About two miles north of them was a division of some 2,000 elite troops under Lord Charles Cornwallis. And about two miles further northwards marched more than 3,000 British regulars under Maj. Gen. Henry Clinton’s command.

Lee made plans to send a portion of his force to the left, in an effort to circle around and trap the enemy’s rear guard. Clinton had other ideas. He ordered his men and those under Cornwallis to reverse their marches and rush towards Monmouth Court House.

Seeing Cornwallis’s division marching toward the village, and three regiments under Lafayette on his right doing the same, Lee scrapped his plan. Instead, he ordered a brigade commanded by Gen. James Varnum to march to the right and follow Lafayette.

Lee dispatched one of his aides, Maj. John Mercer, to order brigadier generals Charles Scott and William Maxwell to maintain their positions in the center of Lee’s line. But Scott and Maxwell were nowhere to be found. Scott mistakenly thought that the Continentals in Varnum’s Brigade were retreating and, without orders, he ordered his 1,440-man brigade to retreat one mile back through the Middle Morass and into woods. Scott persuaded Maxwell, in command of a 1,000-man brigade, to do the same. A shocked Lee then wisely ordered a retreat so his badly outnumbered men could re-cross the two morasses and join forces with Washington’s main army before confronting Cornwallis and Clinton.

At Lee’s court-martial, the court-martial board asked Lt. Col. William Smith why his unit had retreated.

I formed the regiment on the right and presented a front to the enemy. Colonel Jackson then returned and desired me to lead the regiment over the morass upon an opposite height. I asked him if he had any particular orders for it. He answered he had not, but thought it best. I begged him not to stir without orders. He then left me a second time, returned in the space of ten or fifteen minutes, and repeated his request. I asked him if it was his orders for me to lead the regiment. He told me he thought it most proper.[7]

Smith, upset at retreating without receiving orders from Lee, led Jackson’s detachment back through the nearby Middle Morass.

Jackson’s retreat gave the portion of Lee’s detachment in its area the impression of a retreat. Colonel William Grayson of Virginia had minutes earlier ordered Jackson to move forward and seize a hilltop. Now he saw Jackson and his men retreating back through the morass.[8]

Major John Mercer then appeared on the scene. By then he had become aware that Scott’s and Maxwell’s brigades had disappeared and that Clinton’s entire division was converging on Monmouth Court House. Mercer, under authority of General Lee, ordered Jackson to retreat.[9]

As Jackson’s detachment emerged from the woods west of the morass, a second incident occurred that caused some of the detachment’s junior officers to question Colonel Jackson’s judgment. With Cornwallis’s elite troops about to charge out of the morass from the east, General Lee began organizing a defense at the Hedgerow, opposite the exit point of the morass. Lee realized his entire detachment could not make a stand there, but it would do to delay the enemy’s advance while allowing his men to re-cross the West Morass, proceed to higher ground on Perrine Ridge, and wait for Washington’s main army to come up in support. In fact, the main combat of the day would shortly occur at the Hedgerow, where two Continental regiments, one from New York and the other from Rhode Island, supported by artillery, performed excellently in fierce fighting against Cornwallis’s finest troops.[10] But Jackson’s men missed their chance for glory.

Testimony at the trial explained Jackson’s actions. With no other aides available, Lee had instructed Maj. John Clark, an auditor of accounts on General Washington’s staff, to order Jackson’s detachment to form behind the rail fence at the Hedgerow. But Jackson did not know Clark and refused to abide by the order, preferring to continue to march his fatigued troops toward Englishtown.

Seeing the confusion, Lee rode to the rear of the column, accosted the second-in-command, Lt. Col. William Smith, and ordered him to take Jackson’s blue-coated detachment back to the Hedgerow. Smith barked out the order for the detachment to halt, come about, and march back to the Hedgerow. However, only half the detachment obeyed the order, with the front half continuing to march away. Lee spurred his horse toward Jackson, yelling “where is that damned blue regiment going.” Confronting Jackson while grabbing his sword, an angry Lee demanded an explanation. Jackson told Lee his men were in no condition to fight after fast marching earlier in the day and should be allowed to continue their retreat. Seeing the exhausted soldiers, Lee reluctantly agreed, but asked Jackson to take a post nearby. Jackson kept marching his men all the way back to Englishtown.[11]

The testimony at Lee’s court-martial about Jackson’s detachment angered its junior officers. Their July 26 petition requested that a military court investigate Jackson’s conduct. Finally, the new commander of the Rhode Island theatre, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, agreed to hold a court of inquiry to determine if Jackson was guilty of misconduct that would justify Jackson being subject to a more serious court-martial. If the court martial trial’s verdict against Jackson was that he was guilty of misconduct, the sentence could be to terminate Jackson’s service in the army—or worse.

On April 17, 1779, the court of inquiry commenced its hearing at the spacious Providence County Court House. The court’s president was Col. Timothy Bigelow of the 15th Massachusetts Regiment of Continentals. The other four officers appointed to judge Colonel Jackson were junior in rank to him—two lieutenant colonels and two majors.[12] This was a common practice in court-martials of Continental officers. Another common practice was followed: the accused officer served as his own defense counsel. Testimony was taken from April 17 to 19 from five of Jackson’ officers—each of whom had signed the petition against Jackson. The proceedings were postponed until July 5, 1779, when Jackson gave his closing statement.

At the April 1779 sessions, from the testimony of the junior officers, it became clear that Jackson had pushed his detachment too hard in the morning on the way to the front, with the result that the unit’s fighting effectiveness had been compromised. This mistake was probably Jackson’s most damaging one, but it was hardly one for which he could be court-martialed. The impact of the incredible heat may also have affected the judgement of Jackson himself.

Maj. Lemuel Trescott was first called to the stand. In cross-examination, Colonel Jackson asked Trescott, “When I received orders from General Lee to move on in front did I not push the men forward with the greatest cheerfulness in order to reach the front, and in doing so were not the men pushed so hard that they were entirely overheated and fatigued?” Trescott responded, “really I think the men were pushed too hard.” Jackson continued, “When we halted in the wood, did not a number of men faint on the spot?” The major answered, “I do remember it well and attributed it to our marching so fast when we were advancing.”[13] By his questioning, it was clear that Jackson would use his unit’s being driven too hard and becoming exhausted as a main part of his defense.

Captain Ezra Lunt, called to the stand, agreed that “Col. Jackson was in the front and hurried the men rather more than I think was necessary for action. On our march we met the Inspector General [Baron von Steuben], who desired us not to march so fast.” Shockingly, on the detachment’s march beyond Perrine Ridge towards Englishtown, Lunt testified, “I fainted and flung myself into the woods and lay till near night, when I joined the party again.” Lieutenant Samuel Rogers also testified, “The men were much fatigued and worn down with heat, so that many fainted on our way back to the main body of the enemy [i.e., to the Hedgerow].”[14]

Captain Lunt also testified that when Jackson’s detachment had passed through the Middle Morass and reached the open field, spotting the enemy, the men were halted and Jackson gave a short inspirational speech: “Col. Jackson rode from right to the left of the battalion and gave the troops a short harangue. . . . ‘My lads, if there be any of you who have not a mind to go into action now is the time for you to fall out.’ The troops all seemed inclined to go into action.” Shortly afterwards, an enemy’s cannon ball took off the arm of a soldier; Jackson then ordered his men into a hollow out of the line of fire, which Lunt called a “very prudent step.” Colonel Bigelow asked Lunt whether Jackson’s “harangue” was spoken “with a design to spirit and encourage” the troops, and Lunt responded in the affirmative.[15]

The adjutant of Jackson’s detachment, Thomas Edwards, testified on April 19. He played a key role in Jackson’s decision-making at the front, and would go on to serve as judge advocate general of the Continental Army, in charge of bringing court-martial cases against generals and other officers, from October 1782 to November 1783. This portion of Edwards’s testimony picks up where Lunt’s ended.

Col. Jackson soon after this called Col. Smith [Lt. Col. William Smith] and asked him if he did not think it best to file off by the left through the morass. Col. Smith answered, “by no means without orders.” Just upon this Col. Grayson called to Col. Jackson and ordered him to form upon the height. Col. Jackson asked if he had any cannon there. Col. Grayson said, “No, but form.” . . . Col. Jackson ordered me to ride up on the height and see how the enemy came on. I rode up and on my return found Col. Smith with Col. Jackson. I told [them] the enemy were coming on in a heavy column. Col. Jackson then said to Col. Smith, “Well, Smith, I think we had better file off.” “By no means without orders,” replied Smith, “but you must do as you please.” “Well,” said Jackson, “by God, I’ll do it.” We then filed off by the left. As we were going off, I being in the rear, Col. Grayson called to me and asked where we were going. I replied I cannot tell, Col. Jackson is in front leading them off. We then went into a wood where we halted a short time, but soon received orders to retire still farther . . . We were ordered to strike into a thick wood and deep morass.[16]

Lieutenant Thomas Turner testified, “I heard Col. Jackson tell Mr. Edwards to go up and reconnoiter. He went and soon returned informing him the enemy were coming. We were then ordered to retreat, and that through the morass before mentioned.”[17]

While Edwards was correct at the time that Cornwallis’s detachment was “coming in a heavy column,” he gave the wrong impression. At the time, Cornwallis was heading towards the village of Monmouth Court House to the southeast and therefore posed no immediate threat to Jackson and his men. Edwards had arrived at the same bad conclusion that generals Scott and Maxwell had done.

It was true that after reaching the village, Cornwallis could continue on a road towards Englishtown and might then be in a position to cut off Jackson’s detachment. But if Jackson had stayed put, Captain Mercer would have come by a short time later to order Jackson to retreat as well (after Mercer learned that Scott and Maxwell had disappeared from the battlefield). And just because the enemy was approaching did not mean Jackson had authority to retreat on his own.

Adjutant Edwards also testified about Jackson rejecting orders from Maj.John Clark:

Just as we were marching off, one of Gen. Washington’s aides [Clark] came up to Col. Jackson and ordered him to form his men in the line [at the Hedgerow]. The Col. answered his “men were so fatigued they were not able to stand.” The aide replied, “I suppose they are not more fatigued than the others that have been in the field the same time.” The Colonel again replied “they (meaning the men) are dropping down in the ranks, besides, Sir, I’ve Gen. Lee’s orders to go into the rear to refresh.” “If that’s the case, or if you’ve Gen. Lee’s orders,” replied the aide, “I’ve no more to say.” Col. Jackson then rode forward a little way and turning back called to Captain Van Horn who was leading off in front, “come on, Captain Van Horn, come on.” We marched back to Englishtown.[18]

In cross-examination by Jackson, Edwards conceded that at the time of the conversation with Clark, some of Jackson’s men dropped from the ranks from sun stroke and that “several were carried off the field.”[19]

Trescott next testified about events at the Hedgerow leading to Lee’s outburst at Jackson. While not nearly as famous as Washington’s angry confrontation with Lee that would occur about ten minutes later, it was a rare rebuke expressed on the battlefield.

Before we left the field, I saw Gen. Lee, who called Col. Smith and asked him who gave orders for them men to retreat? Col. Smith made answer that he was not commanding officer, that was Col. Jackson, upon which Col. Jackson came up to Gen. Lee and represented his retreat as a mistake in orders. Gen. Lee seemed to be very angry and said, “by God, Sir, I will let you know that I am your general and that [you] had no business to leave the field without my orders.” Part of us soon after retired to Englishtown.[20]

Lieutenant Turner testified further about Lee’s angry confrontation with Jackson:

I observed Col. Smith with about half of the detachment . . . to a railed fence [at the Hedgerow]. After we got there we tarried some time. But before the enemy came up, where I supposed we were formed to resist, I found we were retiring. Then I looked round and saw Gen. Lee on horseback and Col. Jackson at a considerable distance with a pistol in his hand. Gen. Lee immediately halloos, “where is that damned blue regiment going?” Col. Smith stepped up and told him ‘twas not his orders, but his superior officer’s, alluding to Col. Jackson. Col. Jackson then came up. Gen. Lee turned round and said to Col. Jackson, “by God, you are not the commanding officer here, I am.” Then [Lee] ordered us to form. We did not but joined the other parts of the detachment and marched again to Englishtown.[21]

The court of inquiry adjourned on April 19. The affair must have created serious divisions between Jackson and his accusing officers. The matter festered and would not be resolved until the court of inquiry met again in Providence on July 5, when Colonel Jackson gave his closing statement.[22]

Jackson first admitted he pushed his men too hard in the morning.

The rapidity of our movements was almost too great, considering the heat of the day and the fatigues we had endured. [We] marched forward ‘till we discovered a large body of the enemy in our front who immediately commenced a cannonade, with some effect. Finding our numbers vastly inferior and being destitute of artillery, I did not think it advisable to advance farther; but as the whole depth of the column was exposed to their shot, I obliqued to the left and displayed under cover of copse of wood, which afforded me a degree of security.

Jackson explained why he ordered his men to retreat, despite lacking orders from General Lee to do so.

We remained in that situation for some time, expecting orders from Gen. Lee, and the enemy advancing to attack us, I found it necessary to change my position and take possession of a height a little to the rear of my left. My reasons were to command a deep morass which would have prevented out retreat, should the enemy have turned our flanks, as it lay in the rear of our first position in the wood. The resolution could not be deemed an intention of retiring from danger, but a changing of ground to advantage. It could not be construed into breach of orders, as I had received none for occupying a particular spot. I was answerable for the conduct of my corps and consequently was bound to adopt such maneuvers as my judgment should direct, in the exercise whereof I held myself accountable to God and my superiors not to those under my command.

Jackson described receiving orders to retreat from Capt.John Mercer, Lee’s aide-de-camp:

We had but just began a movement from our left to occupy the hill when an aide-de-camp arrived from Gen. Lee, who asked me if I had seen Gen. Wayne or Gen. Scott. I told him I had not. He replied, he would be with me again immediately, and rode off. Hereupon, I halted the troops till he returned, which was very soon. He informed me that Gen. Lee gave positive orders for us to retreat, which was complied with instead of occupying said hill.

Jackson next addressed his interaction with Col. William Grayson, which had occurred prior to Mercer returning:

During these movements, a gentleman unknown to me, but said by the witnesses to be Col. Grayson, called to me to form to our right; but not giving me to understand by what authority he pretended to order me, I did not conceive myself subject to his control. My reputation depended upon the propriety of my own conduct and therefore great caution was necessary in receiving for commands what could not justify me in case of misfortune.

Jackson continued:

We had marched but a small distance on our retreat before we were obliged to halt in a grove to recover the men who were fainting and falling out of the ranks in consequence of the heat and fatigue of the day. We had not been long there before a guide appeared with orders to conduct us out of the wood as the enemy were in close pursuit. We renewed our march and were soon met by an aide from Gen. Lee, Scott, or Wayne, urging us to quicken our march. I informed him the men were so much fatigued that it was impracticable. He gave orders to retire into the rear and receive refreshment there provided.

Here, Jackson recounted receiving orders for his men to retreat and to refresh themselves. Jackson did not identify the aide; no other testimony confirmed the issuance of the orders. He also admitted he was not sure if the aide issuing the orders was an aide to Lee or to brigadier generals Scott or Wayne (at Lee’s court-martial, Jackson testified that one of Lee’s aides had issued the order).

Jackson then explained why he ignored Maj.John Clark’s orders to station his men at the Hedgerow. The length of Jackson’s response indicates his defensiveness.

After marching about two miles, we came up with Gen. Lee’s division, which was in a variety of positions. Here a gentleman [Major Clark] came to me, whom I did not know nor seen before, and directed me to form at a certain fence. I told him my men were incapable of more fatigue and we had just received orders for retiring into the rear to refresh. I do not recollect that he mentioned the orders as coming from Gen. Lee, but if he did I did not know him as an aide to Gen. Lee, and could not have justified obeying him, especially as I had requested the General in the morning to show me the gentlemen of his family by whom he intended sending orders. Every military gentleman of experience is well acquainted what confusion and contrariety of orders are frequently give in the field. It is not uncommon to be accosted by several aides nearly at the same time from different general officers, directing to different objects. It is extremely requisite in those circumstances for every officer to confine his attention to the proper channel through which he is to be ultimately guided. For instance, it would be absurd for a colonel in the left wing of the army to receive orders from a general officer in the right, unless detached for the purpose. And although it appeared afterwards that this gentleman was sent by Gen. Lee, which occasioned the general to show warmth upon the occasion, yet upon being informed by me that my not forming at the fence was through a mistake, being unacquainted with the messenger, he was perfectly satisfied and ordered Lt. Col. Smith, who had formed a part of the detachment at the fence, to march off with me. I cannot imagine that my conduct in this particular can merit censure. I was scarcely acquainted with an officer in the army and might have been led into unpardonable blunders, by adhering to the declaration of strangers. This gentleman, who is said to be Mr. Clark, an auditor of accounts, was not in the military line, nor appointed in orders to act as aide to any officer.

Jackson explained why his detachment marched all the way to Englishtown.

Gen. Lee immediately after ordered me to form to another fence, which we were executing when he countermanded the order in person and told me to march off as he meant to effect a retreat. While retiring, an officer came to me and ordered me to form again, but upon acquainting him with Gen. Lee’s last order, he replied in a true military style that he had nothing more to say. We finally retired to Englishtown and there formed the line under the command of Baron Steuben.

The court of inquiry considered one last piece of evidence, a note from Brig.Gen. James Varnum of the Rhode Island Continentals. Varnum summarized a recent discussion he had with Lieutenant Colonel Smith, just before Smith’s transfer to Spencer’s Regiment in a new department in early April 1779. Smith explained to Varnum that he was not Colonel Jackson’s enemy and recognized that Jackson was a brave and sensible officer. Smith continued that, as Varnum related, “although he discovered on that day some little improprieties, he conceived them the mere results of his [Jackson’s] great fatigue, and thought he [Jackson] behaved as well or better than could have been expected from a gentleman who had never seen actual service.”[23] With Smith departing Rhode Island, he asked General Varnum to convey his message, presumably to the court of inquiry when it next sat. This hearsay evidence was allowed into the record.

Why had Smith softened his stance against Jackson (ignoring his swipe at his commander for lacking battle experience)? It was probably mainly because Jackson’s detachment had redeemed its reputation by performing superbly during the Battle of Rhode Island on August 29, 1778. In the action on the east side of Aquidneck Island, while serving in an advance party, Jackson’s men stood toe-to-toe against oncoming British regulars. In the action on the west side of the island several hours later, Gen. Nathanael Greene ordered Jackson’s men to charge Loyalist regulars, whose attacks had been stymied by Continentals (including by formerly enslaved men enlisted in the “Black Regiment,” the First Rhode Island).[24] The charge by Jackson’s men broke the enemy’s ranks, causing the Loyalist soldiers to flee the field of battle and leave their dead and wounded behind. Greene exulted in a letter to Washington, “I had the pleasure to see them run in worse disorder than they did at the Battle of Monmouth.”[25]

Colonel Bigelow read the court of inquiry’s conclusions: “The court upon fully and maturely considering the evidence and Col. Jackson’s defense and also the confusion of the advanced corps of Gen. Lee’s division on that day are of opinion that there appears not anything against Col. Jackson sufficiently reprehensible to call him before a Court Martial.”[26] The wording implied that Jackson’s conduct had been somewhat reprehensible. Still, the case against Colonel Jackson was formerly closed.

[1]Christian McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War (Savas Beatie, 2020), chapters 10 and 11.

[2]Charles Lee’s court-martial transcript (“Lee Court-Martial”) is set forth in “Charles Lee Papers,” vol. 3, New-York Historical Society Collections (1874), 1-208.

[3]Colonel Jackson’s Court of Inquiry transcript (“Jackson Inquiry”) conveniently appears after Lee’s Court-Martial transcript in ibid, 209-28.

[4]James Thacher, A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1783 (Corner House Historical Publications, 1998; originally published 1823),170-71.

[5]The petition was signed by sixteen officers, ten from Jackson’s own regiment, four from David Henley’s Regiment, and two from William Lee’s Regiment (these three regiments made up Jackson’s detachment). See Complaint Against Col. Jackson, July 26, 1778, Jackson Inquiry, 209-10.

[6]For details of the battle, see McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis, chapter 8.

[7]Lee Court-Martial, 86-87 (italics added).

[8]Ezra Lunt Testimony, Jackson Inquiry, 219.

[9]Lee Court-Martial, 87 and Jackson Inquiry, 123.

[10]For a description of the fierce combat at the Hedgerow, see McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis, 146-52.

[11]Lee Court-Martial, 84-85; Jackson Inquiry, 121 and 124; John Clark Statement, Sept. 3, 1778, attached to John Clark to Charles Lee, Sept. 3, 1778, in ibid., 232.

[12]The other court of inquiry members were: Lt. Col. Ebenezer Sprout of Shepard’s Regiment, Lt. Col. Elijah Vose of Vose’s Regiment, and Maj. Lebbeus Ball of the 4th Massachusetts, and Maj. William Perkins of the 3rd Continental Artillery. Jackson Inquiry, 210.

[16]Ibid., 218-19 (quotations added to original text).

[22]The following quotes are from Colonel Jackson’s Closing Statement, July 5, 1779, ibid., 224-27.

[23]James M. Varnum Note, July 5, 1779, ibid., 227-28.

[24]See Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Joint Operation in the Revolutionary War (Westholme, 2014), 179-93.

9 Comments

This is a nicely done piece. And the book is strongly recommended.

Thanks John, on both counts!

Many thanks for that excellent analysis. As the article demonstrates, because they offer detailed testimony from a range of witnesses, courts of inquiry / courts martial are wonderful sources for historians. They really focus in on specific events, adding a very different and far more personal ‘voice’ to the official reports.

Thank you Stephen! I agree with you on the usefulness of court of inquiry/court-martial transcripts as sources.

It seems to be in fashion today to exonerate those of the Revolution that would easily have lost the cause and repudiate those who actually lead the cause to its successful conclusion.

Lee was a foul individual in two armies. During his capture he wrote notes and plans that could have easily been used by the King’s troops against the rebellion – items of this sort are quickly swept under the rug. In their book, Lender and Stone readily admit Lee faulted in communication, reconnaissance, etc but, again push this aside while in the case of Washington and others this same criticism is decried poor generalship.

Let’s get over it, Lee had been away for a prolonged period of time “in capture,” did not know the current troops and associated particulars and was generously given a command by Washington that should have been pre planned to the fullest. He failed and deserves the repercussions.

Hi Eric. I am always glad to find someone who has strong views! As I set forth in my recent book, George Washington’s Nemesis, I agree that Lee committed rank treason when he was a captive of the British and that historians have previously tended to brush it off as a mere lark or due to his temporary instability. As I argue in the book, he essentially held the same views expounded in his treasonous document throughout his fifteen-month captivity. I also agree with you that he was a disruptive force within the Continental Army and was overly critical of Washington, the indispensable man. But I also argue that Lee was unfairly convicted for failing to attack the enemy and for an unwarranted retreat at the Battle of Monmouth. I believe he did a good job in the battle responding to unforeseen circumstances, some not of his making, and may have saved half the Continental Army. Other officers, including some of his accusers, deserved blame. Perhaps you can read this part of the book, which is based largely on the court-martial testimony of officers who fought at the battle, and let me know if you agree.

Thank you for your insightful and fair response

I will indeed obtain a copy of your book

Always pleasure to exchange discourse with one who appreciates the time and times of the revolution

Eric

I read somewhere that Lee was recorded as accepting a cash bribe from Britain.

While Smith went easy on Jackson it was probably because he had gotten out from under him and appointed to Oliver Spencer’s Regiment. When he asked G. Washington for a transfer in April of 1779 he did not hold back on his feelings about Col. Henry Jackson.

Hi Ken. There are many myths about Charles Lee, only a few are true. You can read about many of the accusations against Lee in my “George Washington’s Nemesis” book, including the myth about his receiving a cash bribe from the British after his suspension from the Continental Army. Interesting point about Smith complaining to Washington about Jackson in April 1779.